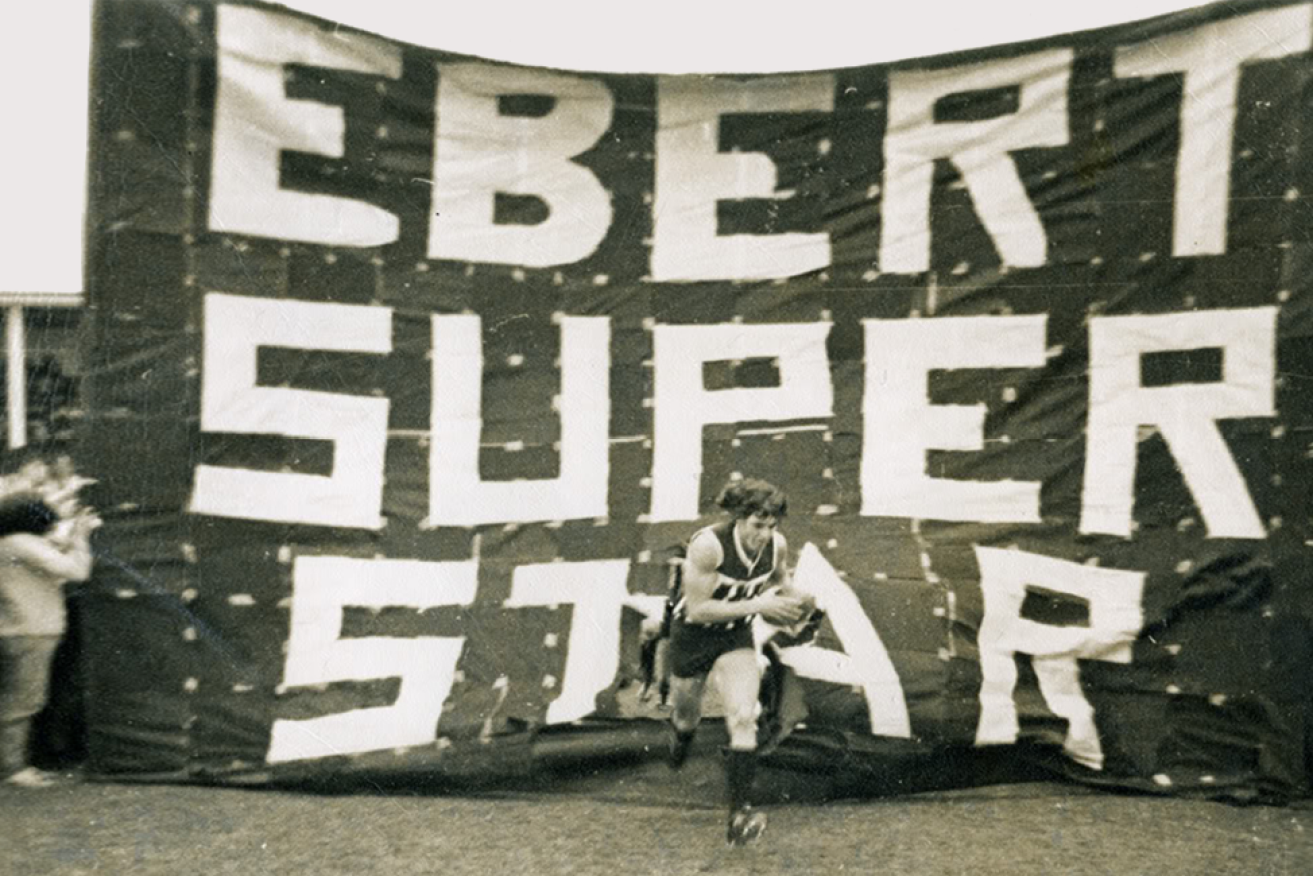

Robran on Ebert: The footy legend facing his greatest test

Four-time Magarey Medallist Russell Ebert is today in a battle to beat cancer. His SANFL debut came on this weekend back in 1968 as another legend, Barrie Robran, started his own march towards multiple Magarey honours. Robran spoke to Michelangelo Rucci about Ebert – his rival and friend.

Photo supplied: Port Adelaide Football Club

Barrie Robran, Russell Ebert and Malcolm Blight took command of the SANFL’s mahogany honour board from 1968-1980; eight of 13 Magarey Medals, five in a row from 1970-1974.

They are the only modern-era footballers with statues outside Adelaide Oval.

“And that statue depicts Russell just how he was as a player,” says Robran, one-time football rival, long-time friend and confidante while Ebert battles acute myeloid leukemia.

“The ball is tucked under one arm, he is starting to lift his eyes and turn … and you know he will get the ball to a team-mate. He was a great deliverer of the ball – unlike many professional footballers today.

“It shows his determination, and that is not just in football with Russell.”

Photo supplied: Port Adelaide Football Club

Ebert and Robran. They were the superheroes of South Australian football when the television era began in the 1960s. By the time black-and-white vision made way for colour and early evening replays were replaced with live telecasts, the debate was: Ebert or Robran? Who was better?

Both came to Adelaide in the latter half of the 1960s from South Australia’s rich country cradle of footballers. Robran in 1967 from the Iron Triangle via Whyalla, Ebert from the Riverland through Loxton to make his league debut in April 1968.

He was an 18-year-old eagerly accepting the challenge of filling the vacancy at full forward while Eric Freeman was on an Ashes cricket tour in England.

By the end of that 1968 season, Ebert was Port Adelaide’s leading goalkicker, Robran was wearing the first of three Magarey Medals (followed up in 1970 and 1973) and taking note of the teenager who would become worshipped by Port Adelaide fans.

“We never played against each other that year,” recalls Robran, who was with his North Adelaide team at Alberton Oval for Ebert’s second league game in April 1968. “But my first real memory of Russell is from the final series in (September) 1968. He was making his mark on the scene.

“I have that image of a bouncy, robust, very competitive player. You couldn’t help but notice Russell while he left a very strong – and very good – presence on the field.”

Today, while 71-year-old Ebert has intense treatment in hospital, the Ebert-Robran storyline is not about a beautiful on-field rivalry that still sparks debate as to which champion was the greatest player in South Australian football history.

Now it is about two mates standing side by side while one is fighting for his life.

Robran admires his long-time friend for the way he is approaching the challenging battle against cancer. It is true to the modesty the intensely private Ebert always sought to command while being showered with seemingly endless superlatives during his 445-game league football career at Port Adelaide in the SANFL, North Melbourne in the VFL and South Australia in State football.

“(He is) very positive,” says Robran, who is in weekly contact with Ebert. “Russell always has that way of leaving the impression – no matter how dire the situation – that some good will come along.

“He is not wallowing in self pity. That’s Russell. He has a very positive attitude to everything he does.”

Remarkably – more so considering how Ebert-Robran was a major theme of SA league football during the 1970s – the two superstars knew very little of each other while drawing thousands of fans through the turnstiles in Adelaide suburbia and turning the Magarey Medal counts into their personal chess board.

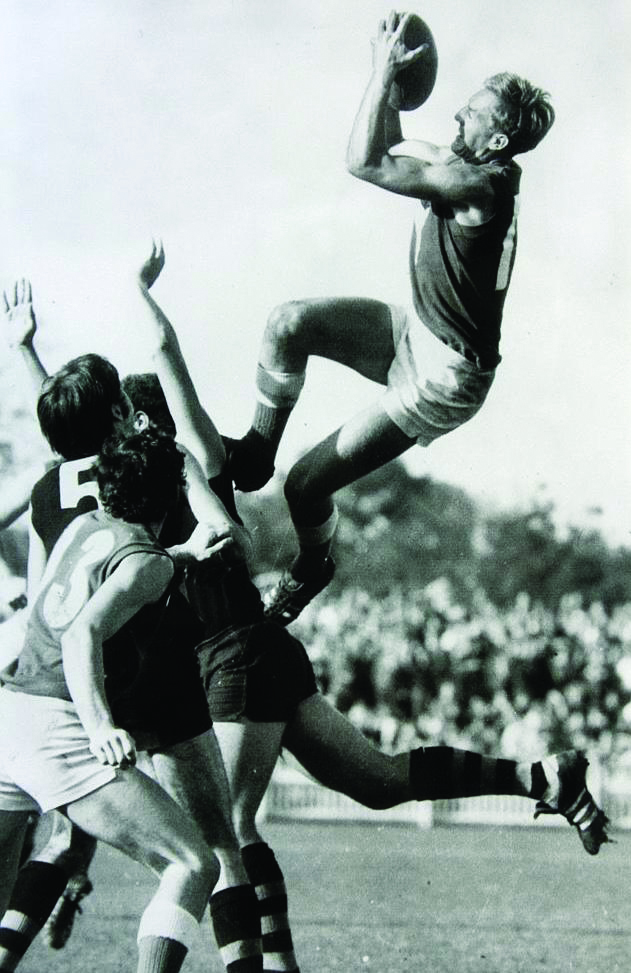

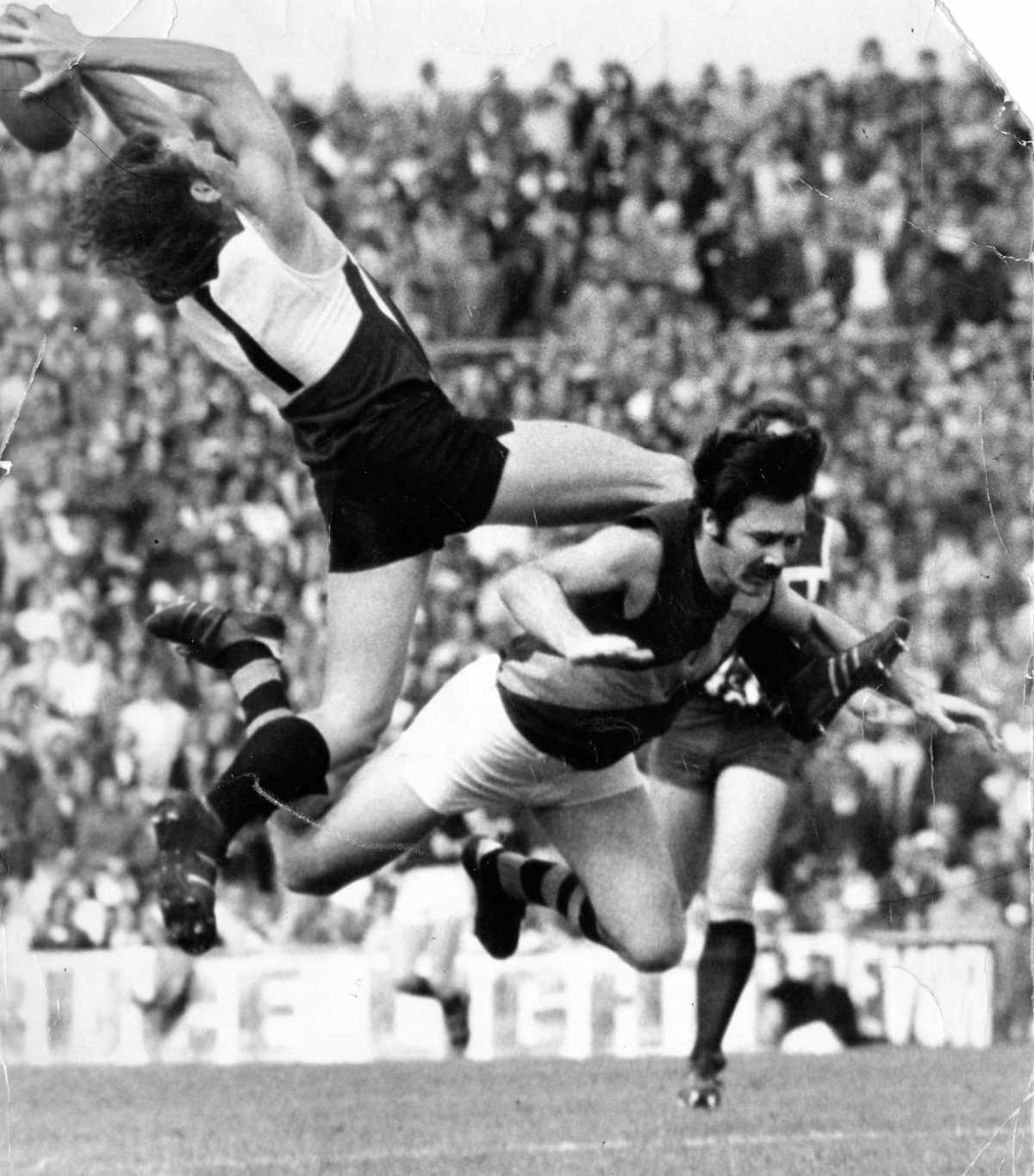

Barrie Robran flies high for North Adelaide. Photo: SANFL

For 13 seasons from 1968 to 1980, they stood toe-to-toe as rivals on the football field in just three matches and as comrades in State colours a dozen times.

“Even when we went away for interstate games we stayed with our team-mates rather than mix with players from opposition clubs,” recalls Robran. “I was with Terry von Bertouch, Bohdan Jaworskyj, John Phillips.Russell was with Peter Woite, Bob Kingston, Ron Elleway … we stuck strong with our team-mates from our clubs.”

Their friendship began in 1980 when Ebert created history as the first player to win four Magarey Medals and Robran limped into retirement having battled to 201 league games on a battered knee wrecked by Leigh Matthews in a State game at the SCG six years earlier.

“We were ‘recruited’ for the Crippled Children’s Association (now Novita) for voluntary fundraising; and we did that together for 25 years,” said Robran.

CCA-Novita marketing and community liaison manager Robyn Chaplin gathered a small group of South Australian sporting greats – Ebert, Robran and Glenelg captain Peter Marker from SANFL league football ranks – to spearhead campaigns that went well beyond finding sponsorship cash for the Crippled Children’s Association.

This was where Robran came to know Ebert for far more than the football talents that preceded the man dubbed as a football god.

“We were not just fundraisers, we were ambassadors for the cause, and Russell took to this with qualities that already defined him as a footballer and much more,” Robran said. “He had more than dedication to the cause; he had sincerity. And sensitivity. He had untiring enthusiasm to make sure we were successful.

“Again, like today, Russell was always thinking of others. That is his nature; very friendly, very obliging with people, very welcoming. He always has been this way, always will be.”

The media image from Ebert’s football career as a player and coach at Port Adelaide and Woodville is contradictory because – like Robran – Ebert was reluctant to be put on a pedestal or stand above his team-mates with any saturation public profile.

He could be suspicious, even brusque, with reporters seeking a quote and photographers wanting another image to plaster on the front or back pages of Adelaide’s competing morning and afternoon newspapers of the era. But away from the cameras …

“Maybe that was our country upbringing,” says Robran. “We grew up wanting to be one of the boys (rather than one of a kind). People will say they were thrilled to get the chance to meet Russell while we raised millions of dollars for Novita. But Russell was just as happy greeting and meeting people, he was very welcoming.”

Those three statues at Adelaide Oval; Robran at the southern entry, Blight at the Victor Richardson Gates in the south-eastern corner and Ebert from the King William Road entry in the east – put in bronze the question as to which superhero from the 1970s is South Australia’s greatest footballer.

“If that is the case (the debate is just among three), we should respect each of us had different abilities,” says the ever-modest Robran. “It is nice to be mentioned with those two names.

“Russell has four Magarey Medals (1971, 1974, 1976 and 1980), so he is the most-decorated in this State,” adds Robran of Ebert who also has the record for games played (391) and best-and-fairest titles (six, 1971, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1977 and 1981) at Port Adelaide.

“This is certainly a tribute to his brilliance and fairness.

“As a player, Russell always was in control. He could play ‘high’, and there are not enough photographs of his high marks. Thankfully, you can see how good he was for high marks on video.”

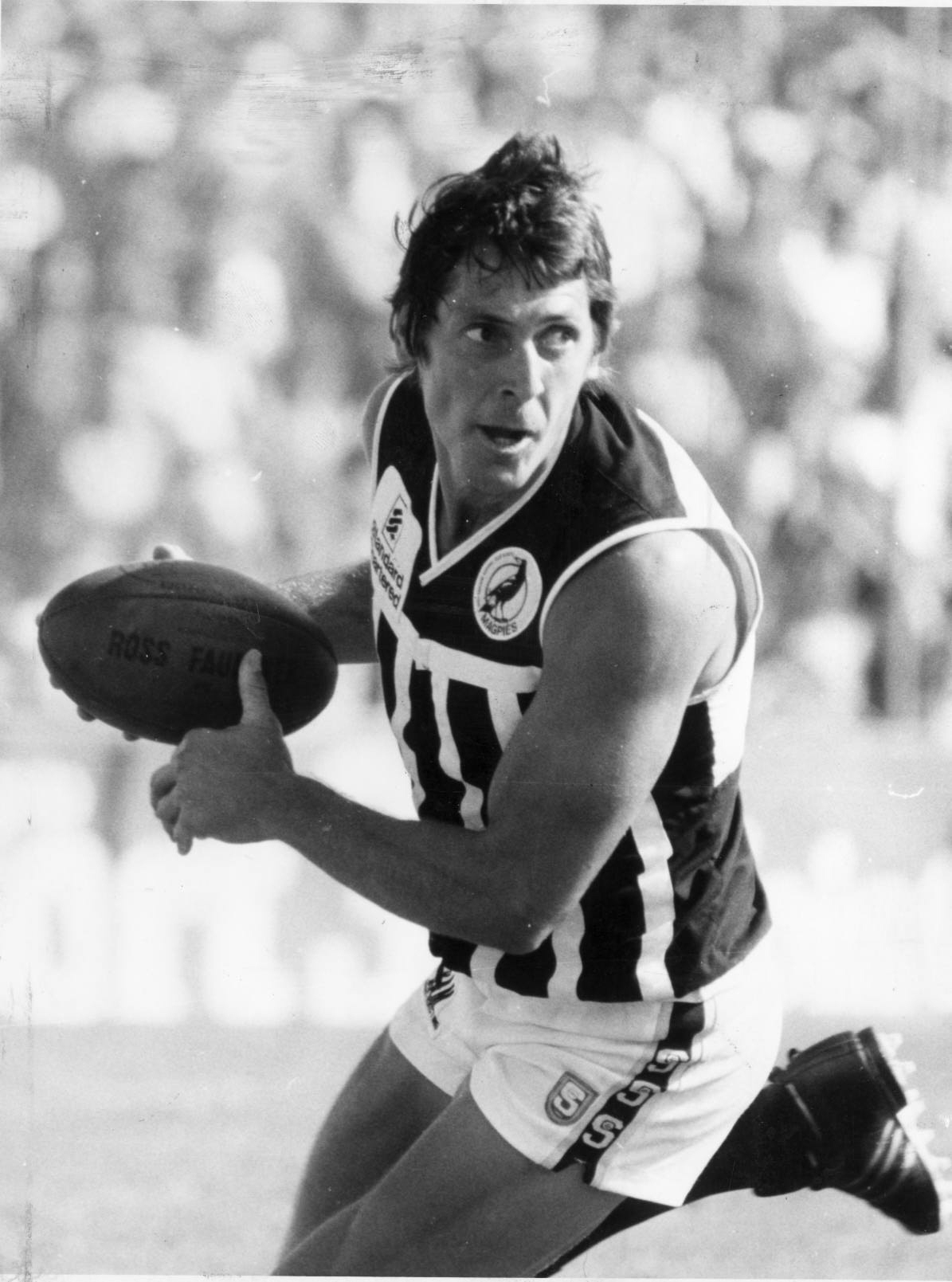

Photo supplied: Port Adelaide Football Club

“He was a great player when the ball was on the ground. This too was his strength, even as a player who stood at 6’2. He could play very well ‘high’ and ‘low’.

“Russell also never lost his feet. And he is famous for how he used his hands with that overhead handball; for that to be remembered 40 years on is quite an achievement. That handball, and the way it mesmerised opponents, was brilliant.

“Handball was not a feature of the Port Adelaide game when Russell started playing league football in the 1960s. He was the exception and Russell started handball at Port Adelaide as a way to bring his team-mates into the game.”

There are just three Ebert-Robran match-ups from 1969-1972. Only one was with both champions at centre.

“One at Alberton, where he shaded me, and I’d like to think I returned the favour when we were matched up as centremen at Prospect,” Robran said.

“And then there was that other game at Prospect late in the 1972 season.”

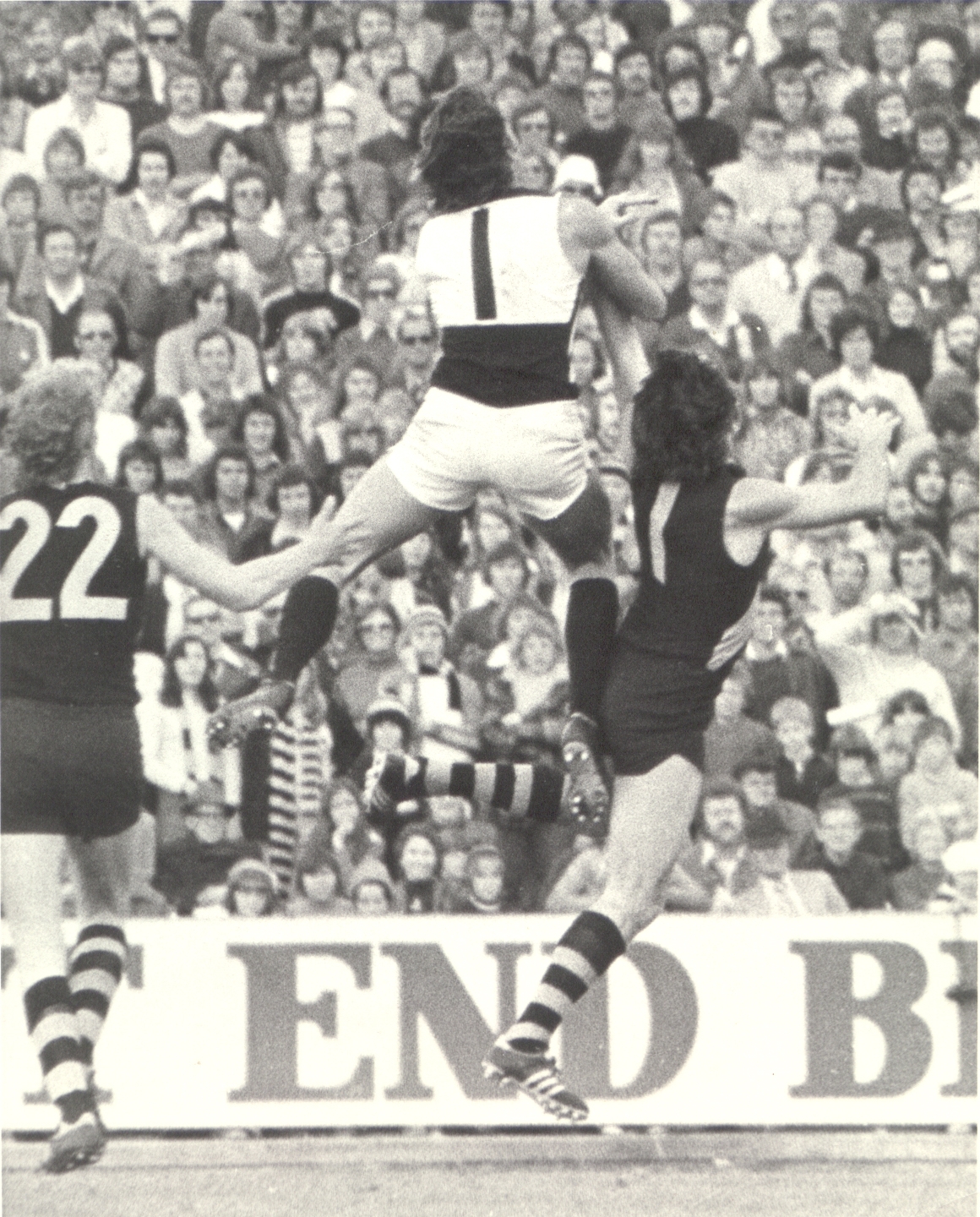

Round 20 on August 26, 1972. The match was billed as an SANFL grand final preview, the build-up dominated by the dream match-up of the men who had won three of four Magarey Medals from 1968.

“I was at centre half-forward, Russell at centre half-back and he cleaned me up while Port Adelaide smacked our butts (by 77 points),” recalled Robran of the day 15,895 filed into Prospect Oval and many more watched the black-and-white edited replay on television that evening.

Ebert kept Robran scoreless.

“It was weeks before the finals and that result left us worried about our premiership defence,” said Robran, “and I didn’t play against Russell in the 1972 grand final (won by North Adelaide). My brother (Rodney) got that job.

“It was daunting to play on Russell. You knew you were up against a champion,” adds Robran, the first South Australian to have “Legend” status in the Australian Football Hall of Fame.

“You would always be trying to work out how best to play against such a great player. He was so versatile in that he could play centre, centre half-back and full forward and play the ball ‘high’ in the air and ‘low’ on the ground. He was powerful. And explosive.”

Ebert during the 1974 preliminary final against Glenelg. Photo: Port Adelaide Football Club

“That statue (at Adelaide Oval) shows it best – he would get the ball, tuck it under his arm and run through the centre of the ground. And his balance. He was one of the best kicks this game has seen … there was power in his kicks. He also mastered the drop kick!”

Robran avoided the VFL despite the constant courting of powerful clubs such as Carlton. Ebert took up the offer from North Melbourne in 1979 when he was 30.

“I am happy Russell did prove himself in the VFL,” said Robran. “He was more than good enough to do it. People do not recognise or appreciate just how good Russell was that year at North Melbourne.”

Robran and Ebert both are remembered as great players who fell short of the ultimate prize as league coaches, while Blight achieved VFL-AFL premierships in both roles.

“I was not ready to coach,” says Robran who took on the dual role of player and coach during his last three seasons from 1978-1980. “I should have stepped away for two or three years before trying my hand at coaching. I was playing with injury, managing a business, bringing up a family with two children.”

Ebert was the last playing coach to take a team to an SANFL grand final – the 1984 Port Adelaide-Norwood classic at Football Park won by Norwood after, as Robran puts it, “(Norwood midfielder) Keith Thomas took the best and most courageous mark ever seen in football”.

Ebert did coach Woodville to its second and last SANFL trophy success – the 1988 Escort Cup night title by beating his former charges at Port Adelaide in the final at Football Park; and was in charge of South Australia’s State team three times from 1996-1998.

While Robran stepped away from football during the 1980s, Ebert kept a high profile after his league coaching career ended by taking up media roles, particularly on radio.

Ebert and Robran both had sons reach the AFL – Magarey Medallist Brett Ebert at Port Adelaide; Matthew Robran at Adelaide and Hawthorn and Jonathon Robran at Hawthorn and Essendon.

Ebert and Robran; two extraordinary men, with extraordinary lives and a friendship built while seeking to enhance the lives of those less fortunate.

As Ebert has repeatedly said since entering hospital at the start of the year, “I have nothing to complain about. It has been a good life.”

True to Ebert’s reputation of finding good in every challenging situation, there is a campaign to make sure Ebert’s absence from Red Cross Lifeblood donor centres is taken up by others. So far, more than 130 people across Australia have joined “Team Russell” to donate blood or plasma.