The tragic hypocrisy of the post-referendum world

Behind the failure of the voice referendum is a hypocrisy so deeply ingrained in Australian society and politics that many of us can’t see it, argues David Washington.

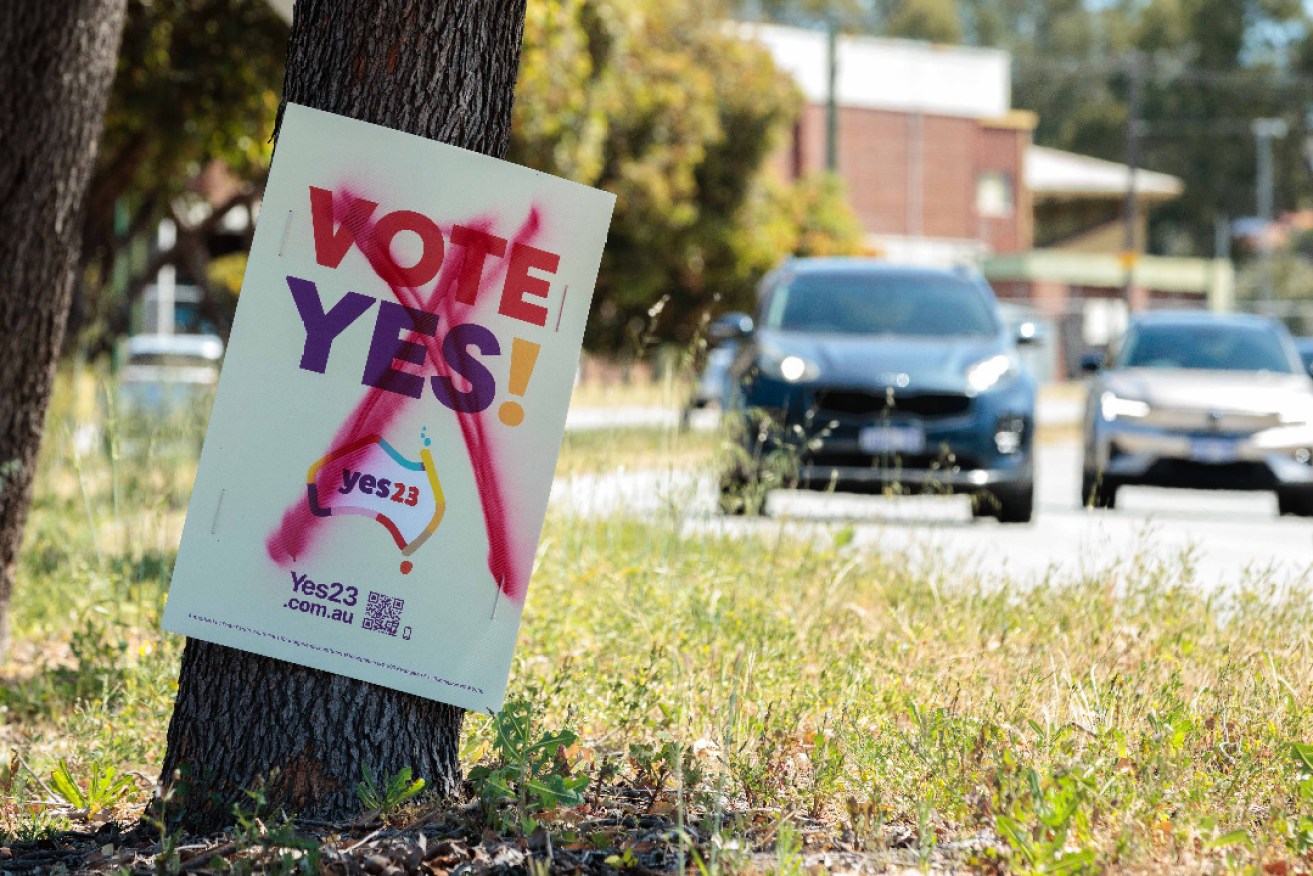

Photo: Richard Wainwright/AAP

At the height of the scare campaign over the expansion of the Hutt Street Centre for the homeless, ‘concerned locals’ published a series of photographs to demonstrate their fears.

Under a heading “the ugly”, there were images of Aboriginal people in the area. They weren’t doing anything anti-social or illegal: they were simply existing on a city street.

Switch forward to this year’s city crime scare, and someone inside Parliament House saw a woman apparently passed out near a bus stop on North Terrace. She was bent in the middle, her head on the pavement, no shoes on her feet.

Instead of immediately running to her side to help, the person identified as a “staffer” took a photograph and sent it to The Advertiser who presented it as an example of “anti-social” behaviour.

Now imagine these people in a different way: a couple of businessmen wearing jackets and chinos on Hutt Street; a woman in her Melbourne Cup finery on North Terrace. How are those moments transformed?

We are so deep into denial, so well-practised at it, so deeply conditioned, we can’t see our own prejudice.

In the post-referendum political world, all signs point to this getting worse.

Not listening

Why would Aboriginal people ever again involve themselves in a government-led engagement process?

The national voice proposal was the result of years of work, with a referendum council supported by a Coalition Government and culminating in an informed consensus from Aboriginal people – the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart.

In South Australia, the idea of a state voice grew out of a process championed by a Liberal Government. Premier Steven Marshall appointed Roger Thomas as Aboriginal Engagement Commissioner in 2018, with a brief to work out how Aboriginal people could be effectively represented to government.

He did this, comprehensively.

Thomas’s report – which Marshall had him present to parliament – recommended a voice to parliament to combat disadvantage and institutional racism, including within the South Australian Government.

“The community is clear about the way forward,” Thomas found. “It is through leadership by Aboriginal people for Aboriginal people and through a genuine and representative voice for Aboriginal people into government and through mutual respect.”

Marshall got some positive coverage in The Australian about his visionary move, and he proudly sent out media releases and social media posts promising to implement a half-elected, half-appointed voice in early 2021.

Unsurprisingly for his COVID-addled administration, that didn’t happen.

Aboriginal Engagement Commissioner Dr Roger Thomas wiping away tears as he delivers a historic address to parliament. Photo: Screenshot of SA Parliament broadcast

The Speirs Opposition – barely a year ago – castigated the Malinauskas Government over its failure to speedily implement a voice to parliament.

Since then, the state Liberals’ principles have blown with the prevailing political breeze.

Using the different model subsequently put forward by Labor as a fig leaf, the Liberal party room – facing an organisational wing falling inexorably into the arms of the hard right – refused to support Labor’s voice model, which envisages a larger, fully-elected body. Thomas, by the way, wanted his body to transition to fully-elected representation.

This week, Liberal leader David Speirs completed his evolution into a non-believer in any kind of Indigenous voice, on the grounds that it divides Australia on racial grounds. An elected body of Aboriginal people is now considered undemocratic.

What will be the next logical extension of the Liberal policy evolution? The abolition of the South Australian Multicultural Commission?

Speirs is inclined to support One Nation MLC Sarah Game’s proposal to repeal the state voice legislation.

The move will fail but the symbolism will be clear to all.

No-one blamed submariners for the waste; Aboriginal people always cop heat for political and bureaucratic failures.

Game herself has gathered plenty of attention in the post-referendum wash-up.

For painful personal reasons, she is passionate about men’s health and wants a series of men-focused policy changes, including the appointment of a Minister for Men overseeing an Office for Men.

She clearly believes men have specific health needs based on their biology and experiences and they need representation – a ‘voice’, if you like – in cabinet and the bureaucracy.

At the same time, she apparently believes we shouldn’t have support structures and programs which focus particularly on Aboriginal disadvantage.

“It’s time for a plan for needs-based support, not race or heritage-based support,” she said this week.

In Game’s world, gender differences are sufficient to warrant separate bureaucratic, governance and support structures, but cultural differences are not.

Elections for the state voice to parliament will be held early next year. The Aboriginal members will join knowing the ears of much of the parliament will be closed to their voice.

Money for nothing

Liberal member for Sturt James Stevens holds the one remaining seat for his party in metropolitan Adelaide.

The moderate former chief of staff to Premier Steven Marshall has been on his own journey in this area.

In the past, he was vocally in favour of the symbolic constitutional recognition of First Nations people. Once he’d settled on ‘No’ to the broader voice proposal, he also settled into a role as a prominent local campaigner for the negative proposition, capping his involvement with an appearance on the ABC’s Q&A, filmed in Adelaide at the beginning of last week.

In his now controversial contribution, he offered his view – somewhat sheepishly – that colonisation had been a positive for Australia.

@natindigtimes Liberal MP James Stevens and actress Natasha Wanganeen entered a debate on ABC’s Q&A after Stevens labelled European colonisation as an “overwhelmingly” good thing. ?: ABC #voicetoparliament #colonisation #britishcolonialism #auspol #abcqanda #jamesstevensmp #natashawanganeen

He was more forthright, though, on one of the key themes of No campaigners – that money is being wasted on Aboriginal programs.

What that has to do with the voice referendum question is unclear, but Stevens wants a complete audit.

“All of the people in charge of spending this money right now are not doing a very good job with it,” he said.

This money, Stevens surely must know, is mostly being deployed via bureaucratic systems designed during his own party’s near decade-long federal rule.

As the ABC’s Laura Tingle pointed out, these federal structures introduced by the Coalition included an Indigenous advisory body whose inaugural chair was prominent No campaigner Warren Mundine.

There is profligate public spending in many areas, but none attracts the political baggage of those funds designed to benefit the most disadvantaged and poorly-served section of the community.

This baggage is part of the enduring myth of Aboriginal advantage.

Governments can burn billions of dollars in other program areas without much blowback, but inefficient spending in arguably the most complex area of administration is given microscopic attention.

Stevens’ party predecessor in Sturt, Christopher Pyne, played no small part in the failed French submarine deal which cost Australian taxpayers $3.5 billion and delivered exactly nothing.

No-one blamed submariners for the waste; Aboriginal people always cop heat for political and bureaucratic failures.

Australia’s defence chiefs spend the annual Aboriginal affairs budget before breakfast: rather than being ashamed, politicians trumpet defence spending. The more the better.

Former Defence Minister Christopher Pyne. Photo: David Mariuz/AAP

Why are South Australians comfortable to spend north of $15 billion on 10 kilometres of South Road – $1.47 million per metre – but are supposedly deeply concerned about a local Indigenous affairs budget which could be run for decades on that sort of money?

The most recent state Budget allocated $4.7 million over four years on “South Australia meeting its partnership commitments under the National Agreement on Closing the Gap” – less than we will spend on four metres of road.

In brutal contrast with the intense focus on Aboriginal programs, the nation’s well-funded culture warriors reflexively defend the wealthiest Australians against attempts to reduce the government largesse they receive via negative gearing, franking credits and numerous other boondoggles.

Why is that?

A long list

This is a brief summary of just a few of the infuriating hypocrisies that poison the debate on Indigenous issues.

We could also talk about a nation that mythologises aspects of its post-European history with religious fervour, but steadfastly denies Aboriginal experiences and histories.

We could talk about the media obsession with Aboriginal “disunity”, despite the demonstrable reality that the non-Aboriginal community is far more divided.

We could talk about the idea of the voice “dividing Australia by race”: as if John Howard didn’t suspend provisions of the Racial Discrimination Act during his Northern Territory intervention; as if the policy of ripping Aboriginal children from their parents wasn’t based on race; as if the historical lie of terra nullius wasn’t part of European colonial strategy to dehumanise Indigenous peoples across the word.

The most gut-wrenching part of the Uluru Statement from the Heart was its anguished reference to “the torment of our powerlessness”.

If politicians really want community healing after a cynical referendum campaign, they should begin by thinking deeply about the nature of this torment.

And stop twisting the knife.

David Washington is a South Australian journalist. He is editorial director of Solstice Media.