PM should trust voters on the Voice

Anthony Albanese has reduced the referendum question on a proposed Indigenous Voice to Parliament to a bare minimum. Matthew Abraham argues the strategy risks creating a space for misinformation to grow.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at the Garma Festival in northeast Arnhem Land in 2022. Photo: AAP/Aaron Bunch

The one lesson every L-plate politician learns early on in the game is a simple one.

It goes like this: Never answer a “yes or no” question with a “yes” or “no”.

In my previous life as an ABC broadcaster, I know from painful experience that the refusal of politicians to give straightforward answers to straightforward questions drove listeners nuts. By a country mile, it was their single most consistent bugbear.

Nuance is the superpower of successful politicians, and the “yes or no” question is its kryptonite. The trick is to always answer questions in a way that creates wriggle room and an escape route.

So it seems passing strange that new Prime Minister Anthony Albanese wants to put a simple yes or no question to the Australian people on his proposed referendum for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to parliament.

It risks jeopardising one of the biggest questions to be put to the Australian community in more than half a century.

The PM used last weekend’s Garma Festival in Arnhem Land to unveil his proposed wording for a referendum to change the constitution to enshrine the Voice.

“We should consider asking our fellow Australians something as simple, but something as clear, as this: ‘Do you support an alteration to the Constitution that establishes an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice?’,” he said.

“A straightforward proposition. A simple principle. A question from the heart.”

Along with the Yes or No question, he proposes adding three sentences to the Constitution. These will require the creation of a body called the “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice”, and that it may make representations to parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The third sentence gives parliament power to make laws about the “composition, functions, powers and procedures” of the Voice. This is where the rubber hits the road. Precisely how will the Voice work? Nobody knows.

Were Australians confused by the complexity of the question? Or did we just understand this was a vote to right a big wrong?

The PM says many details won’t be known before the referendum, because he wants to avoid a repeat of the failed 1999 republic referendum.

“What I am not going to do (is) to go down the cul-de-sac of getting into every detail because that is not a recipe for success,” he told ABC television.

The 1999 referendum on a republic didn’t fail because of too much detail, it failed because of the clashing, giant egos driving the pro-republic bus, divisions exploited with subtle brilliance by the monarchists, and a lack of broad bipartisan support.

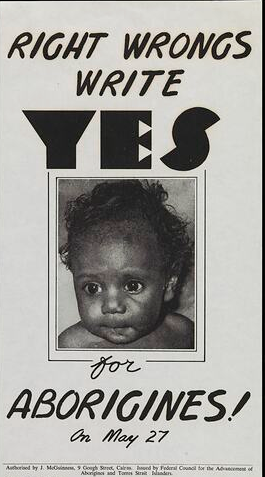

Albanese should have more faith in the Australian public. And if he’s looking back at referendums, he should look back not to 1999, but to the stunning success of the 1967 referendum granting recognition to Indigenous Australians.

Like many of my generation, I grew up thinking this referendum gave Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people the right to vote. That’s wrong. With the exception of WA and Queensland, they could already vote at the state level, although full voting rights weren’t granted federally until 1984.

The 1967 referendum didn’t insert any new words into the Constitution. It removed them.

When our Constitution was written in 1901, it contained only two references to the First Peoples of Australia. Both were appalling.

Section 51 (xxvi) gave the Commonwealth power to make laws for peace, order and good government for “people of any race, other than the Aboriginal race in any state, for whom it was deemed necessary to make special laws”.

Section 127 provided that “in reckoning the numbers of people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted”.

In brief, these meant the first Australians weren’t recognised as part of the Australian population and states could create their own policies for Indigenous Australians. Many of those policies were simply racist and did incalculable harm. Section 51 effectively gift-wrapped the Stolen Generation.

As the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) explains, dispossession was rampant, as was oppression and control of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ lives.

“The states enacted Aboriginal Protection Acts which gave them the legal right to remove children from their families,” it says.

The 1967 referendum expunged the reference to “the Aboriginal race” in Section 51 and repealed Section 127 excluding “aboriginal natives” from census surveys.

And what was the “simple and clear” question?

The 1967 referendum campaign was about fixing injustices.

It was this: “Do you approve the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled – “An Act to alter the Constitution so as to omit certain words relating to the People of the Aboriginal Race in any State and so that Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the population”?

This question was in fact a vote on legislation to amend and repeal the offending sections of the Constitution. Unlike the Albanese plan, the referendum’s horse was very much in front of the cart.

It received 5,183,113 votes, or just shy of 91 per cent in favour, the biggest majority ever for a referendum question in Australia.

In 1967, as a nation, we were less well educated and our access to information was meagre compared to the data now at our fingertips.

Were Australians confused by the complexity of the question? Or did we just understand this was a vote to right a big wrong?

Anthony Albanese is a conviction politician, a leader who wears his heart on his sleeve. He often seems on the verge of tears when talking about matters of social justice, as did the late, great PM Bob Hawke.

This isn’t a bad thing, in fact, it makes a nice change from the previous incumbent in the big chair.

He should have more faith in the ability of voters to navigate the fog to reach the truth.

He must know there’s nothing simple or straightforward about the Voice. By pretending there is, he creates a vacuum that will be filled by misinformation and scare campaigns run by keyboard cowards.

The PM doesn’t want to go down a cul-de-sac but that’s just where the Voice will end up if he’s not careful.

Matthew Abraham’s political column is published on Fridays. Matthew can be found on Twitter as @kevcorduroy. It’s a long story.