Will shopping centres fill the spaces or fall through the cracks?

As we make the final, tentative steps towards our reconnection the rest of the nation and world, economist James Atkinson considers just how ‘changed’ the world we’re moving into will be.

There’s a good chance that we’ll return to something similar to our pre-pandemic lives much more rapidly than many of us assume and many of the ways in which it was theorised we would be forever changed will not come to pass.

For example, it’s likely we’ll be blowing out candles on birthday cakes and shaking hands for a few more years yet.

That said, there is no doubt that history will show the events of the past two years to be transformational in some areas.

One area where changes are likely to be significant, permanent and far-reaching will be in the way we shop.

Even here in South Australia where we’ve been barely impacted since March 2020, many of us will have conducted our first foray into online retailing and others will have turned an occasional purchase into something more routine.

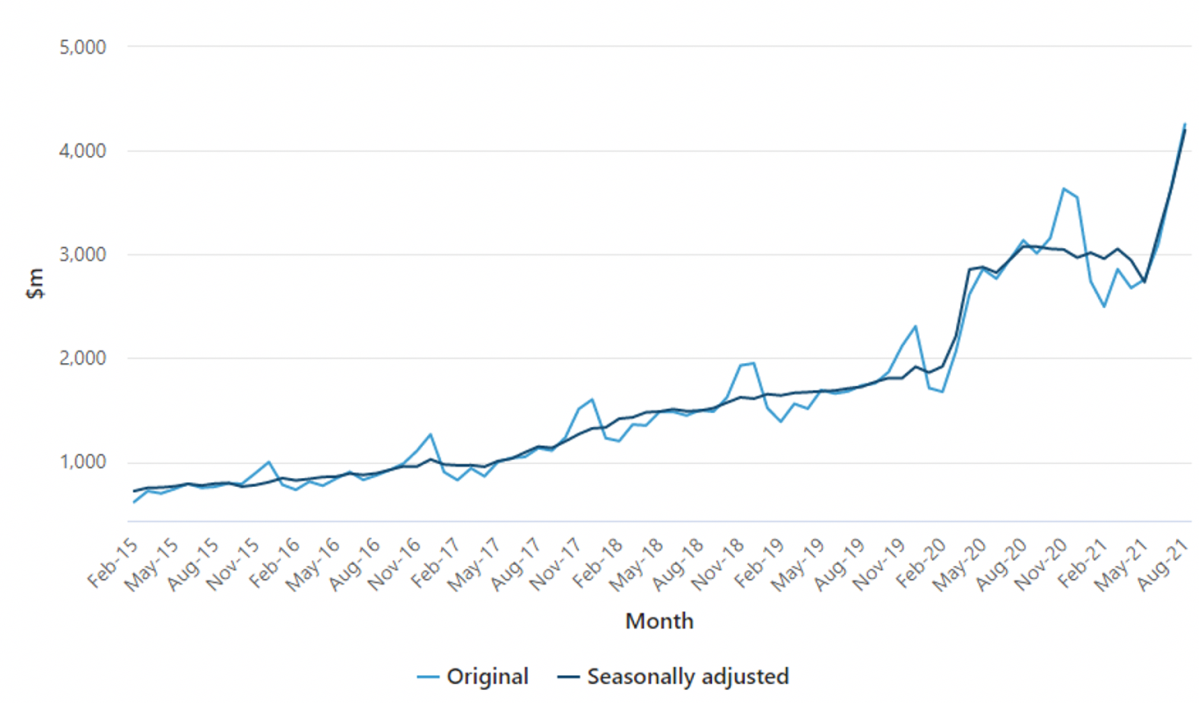

The shift online across Australia is illustrated by ABS data. Prior to February 2020, the sector was growing strongly with turnover doubling in 3.5 years. In the following 18 months growth has been phenomenal – with the share of expenditure directed online rising from 6.6 per cent to 15.0 per cent by August 2021.

Looking at ‘non-food’ retail, the jump was even higher: from 10.9 per cent to 25.1 per cent.

Clearly, extended lockdowns in many parts of Australia will have played a major role in driving this increase but high and growing online expenditure is almost certainly here to stay.

To understand why this is a problem it’s helpful to think about the historical context in how our centres were planned and laid out.

Most were developed at a time when if you wanted to buy something you went to the local shops or perhaps to a regional centre or the CBD for higher order purchases. In short, very little retail expenditure ‘leaked out’ of the system.

Retail planning in this environment was straightforward: build the centres and the people will come. After all, where else could they go? This was a time in which, in the absence of online competition, ugly and dysfunctional retail centres were perfectly adequate.

Post pandemic, however, we live in a world where the online retail sector has been turbocharged by a massive boost in demand, combined with the bringing forward of investments in improving online purchasing and distribution systems and the entry of thousands of new online players. And they’re all competing for a pool of retail spending in South Australia that’s barely growing.

This means that as South Australian retailers and centres emerge from the fog of 2020-21, and as the impact of stimulus measures peter out, they will be competing for a far smaller quantity of expenditure than they were in 2019.

At the same time, the centres in which they are located remain in place – in fact, the quantity of floor space will surely grow, with new centres rightly emerging to service new suburbs in places like Playford and Mount Barker.

So retailers and centres face a growing quantity of retail floor space competing for a diminishing share of retail expenditure.

You don’t need an economics degree to understand that the implications of this sort of demand/supply imbalance are potentially dire and include declining business profits and depressed commercial land values to start with.

This sort of structural imbalance threatens to lead to ‘flight’ from our least appealing centres, which has happened in some US cities where abandoned malls dot urban landscapes.

Here in South Australia, local governments are largely responsible for centre planning.

As the impacts of online retailing on centres becomes clearer, it will fall to councils to plan for changes that are already well underway.

There are a number of strategies that can be pursued to support our centres and local governments should be planning for the future now.

The degradation and potential loss of our centres would also come at a social cost.

At their best, centres are places that bind us. They are democratic spaces where we come face to face with ‘the other’ and where communities are forged.

There’s something very dystopian about a future in which our marketplaces move online, with our physical centres and the communities that rely upon them left to atrophy and decay.

In an increasingly online world it may seem that this shift is inexorable. I’m not so sure, however.

The degree to which we allow our centres to decline is to a large extent a choice we have before us as a community.

With the right mix of interventions, our centres may be given the opportunity to become people-centred places far superior to the dull, utilitarian spaces many of us have relied upon up to now.

Perhaps we may even look back on 2020-21 as a point in time that triggered changes to our retail networks that allowed them to flourish as never before.

James Atkinson is an Associate at SGS Economics & Planning.