Marshall the political outsider whose govt favours insiders

Steven Marshall’s hands-off political philosophy might be well-suited to the pandemic environment, but if you look beyond the COVID headlines some of his ministers have been busy making enemies for his administration.

Environment Minister David Speirs has led an extraordinary attack on the reputation of the National Trust. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Before the 2018 election, InDaily held intimate political forums with the three leaders –Jay Weatherill, Steven Marshall and Nick Xenophon.

Xenophon and Weatherill were both relatively predictable – Marshall was surprising.

I asked the soon-to-be Premier about his vision for the state.

His response was that he didn’t have one.

“We are quite different from Jay Weatherill and the Labor Party who think that it’s the government’s responsibility to drive every single development for a city and a state,” he said.

“We think it’s the people’s responsibility to do that. We want to be an enabling government, but we don’t want to be a government that says that we know what is right for you.”

His guiding political principle was to leave a vision vacuum for the community to fill, which, three and a half years later, might explain the sometimes-confusing nature of the Marshall Government’s approach to governance.

This is particularly clear in its communications strategy.

In psychological terms, they’ve been passive-aggressive. Or, if you like, they’ve been all over the shop.

On one hand, Marshall and his team have been almost stand-offish. No other Premier has deferred so much of the day-to-day communications task on the COVID-19 pandemic to their chief public health officer and the emergency coordinator. Many people see this as a strength; some business people, in particular, haven’t liked it.

Similarly, many ministers have almost no public profile.

On the other hand, other ministers have started to take a confrontational approach to issues that require a defter touch.

One of the feistier ministers in this government is in an unlikely portfolio. David Speirs looks after the environment, water and heritage and, while we are used to South Australian water ministers muscling up on the “upstream states”, it’s his approach to heritage which is raising temperatures.

The idea of consultation is a vexed one for governments. Labor Premier Jay Weatherill famously experimented with participatory democracy, wanting to shift the modus operandi of government from “announce and defend” to “consult and decide”.

He had mixed success, to put it kindly.

By contrast, Speirs and his colleagues appear to have few clear guiding principles in their dealings with the community.

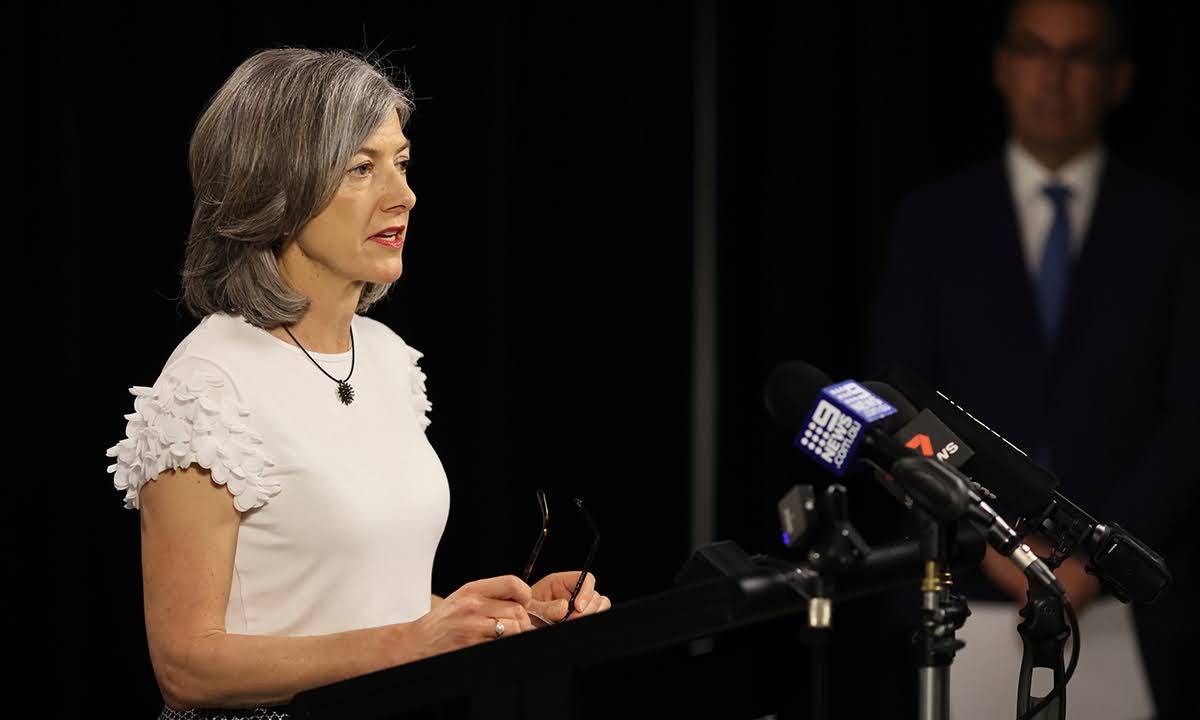

Steven Marshall has been happy to stand in the background while the likes of Nicola Spurrier takes the lead on the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

The growing mess over the future of Ayers House – which should be an unambiguously positive story for the government – is a case study in failed consultation.

The result of the government’s approach is that less than a year out from the election, it has antagonised the heritage-minded in the community, and opened up a rhetorical and legal battle with a venerable community group, the National Trust.

The problem isn’t the substance of what Speirs wants to achieve, which is a more than $6 million spruce-up of Ayers House on North Terrace. The issue is that he didn’t find a way to placate the National Trust, which looked after the historic building for nearly 50 years, operates a museum there, and now faces eviction.

In fact, he did the opposite, inflaming tensions and creating a campaigning point against the government.

The issue first came to public view via one of the Government’s favourite communications strategies – which is all about cosying up to insiders.

Under the deal, the History Trust – a government-funded agency – gets brand new offices in Ayers House, and the Government gets greater control of a shiny “activated” building across the road from its pet Lot Fourteen project.

And the National Trust? They get turfed out and called all sorts of names for complaining about it.

These failings are not unusual for governments, but the increasing impression is that the Marshall Government doesn’t see these communication stumbles as problems.

I can’t recall a Government minister and the head of a state agency publicly attacking a community group’s reputation quite as they did in News Corp’s Advertiser last Saturday.

Speirs said the National Trust can’t bring a building like Ayers House to life. Worse, he says the National Trust is “institutionally unable to collaborate and partner”.

While there’s some inherent irony in that statement given the brouhaha, Speirs and the boss of the History Trust, Greg Mackie, were in lockstep on their anti-National Trust rhetoric.

Mackie echoed Speirs’ criticism, saying the leadership of the National Trust “rejects and eschews” opportunities for collaboration.

Under Mackie’s leadership, the History Trust is a government insider and the Government is backing them to transform and “activate” Ayers House.

The National Trust, led by CEO Darren Peacock, certainly is not, having opened up battles with the government over Shed 26, now demolished, the Urrbrae Gatehouse, set to be bulldozed and rebuilt elsewhere after a community campaign saved it from outright destruction, and the contentious future of Martindale Hall near Clare.

Another insider, Marshall confidant and former federal minister Christopher Pyne, also joined the pile-on in his Advertiser column on Monday, which was based entirely on an erroneous assertion.

“Quite why the National Trust needs to be based at one of the most expensive pieces of real estate in Adelaide is yet to be explained,” he wrote. “It could just as easily be found a decent office space in one of the many commercial buildings in the CBD.”

Leaving aside the fact that the same point could be made about the History Trust, Pyne’s central assertion isn’t true. The National Trust isn’t based at Ayers House – its offices are at Beaumont House on Glynburn Road. The National Trust’s job is to look after historic places.

Could Speirs have avoided outright conflict over Ayers House? I’m not sure, but there’s no evidence he thought through the PR consequences of booting out the National Trust.

In any case, it seems a political misjudgement to appear to be fighting more aggressively over the tenancy of a building than the future of the River Murray, for example.

But fine-grained communications strategy isn’t the forte of many practitioners of state politics in Australia and certainly not this government.

… there are many who are shivering outside the marquee, listening to the faint clink of champagne glasses

While the media landscape has splintered and diversified, the Marshall Government is most comfortable with a limited arsenal of communication concepts: carpet-bombing social media and its sometimes controversial database of electors with targeted messages; paying News Corp a secret but obviously large heap of dough for publishing positive news under the “Future Adelaide” banner; and giving out “exclusives”, again mostly to the Murdoch press.

The latter is what they did in the case of Ayers House. As with the Urrbrae Gatehouse announcement before it, the official media release didn’t contain the full story.

There was no mention of the National Trust getting the flick.

As soon as other media realised it, the strategy only worked to heighten the drama.

Nasty surprises are anathema to effective politics, but it’s something that also happened to the Government on its “good news” announcement over the North-South corridor tunnels.

Some landowners weren’t 100 per cent sure that their properties would be compulsorily acquired until they saw the plans in the paper. A lack of communications forethought is a problem that has been evident for a long time, going back to the Government’s first Budget when Rob Lucas shocked the Liberals’ core constituency with an unexpected land tax hike. Like a number of reform attempts this term, the Government backed down in the face of a concerted campaign.

These failings are not unusual for governments, but the increasing impression is that the Marshall Government doesn’t see these communication stumbles as problems. Rather, they view criticisms as unfair, unjustified whinging from ungrateful outsiders. They seem to have arrived at this point at least as fast, if not faster, than Labor, whose regime was notoriously weighted in favour of insiders and buddies by the end of its 16-year stretch in power.

The problem for the Premier is that there is an increasing number of people and groups who don’t feel the warm and cosy glow of the government’s favour. The opposite in fact: there are many who are shivering outside the marquee, listening to the faint clink of champagne glasses. The Government doesn’t seem to realise how many of them are out in the cold – in business, sport, health, and other sectors.

If the Marshall principle remains one of benign enablement, several of his ministers are filling that void with rancour, at a time in the political cycle when the government needs it least.

The Premier himself commonly avoids public engagement with the tricky problems in his ministers’ portfolios, leaning on his refrain that he’s not aware of the details.

With these ministers, it’s time for the Premier to move from enabling to leading.