A damning set of child protection statistics

South Australia’s expenditure on child protection continues to explode – but is it leading to better outcomes? Simon Schrapel examines the latest damning data on children being placed in out-of-home care.

File photo

Each January, under the cover of summer holidays, a series of reports are released by the Productivity Commission entitled the Report on Government Services (ROGS). These reports canvass a range of activities, from the provision of health services to housing, education, corrections and child protection. They are the product of countless hours of data analysis – and no doubt contentious arguments – by Commonwealth, state and territory bureaucrats. The reports are aimed at assessing the performance of government-run and funded services.

For all the effort invested in producing and publishing the ROGS, they generally go largely unnoticed and reported. While they are incredibly dense documents full of figures, graphs, tables and countless footnotes, they do represent a good way to hold our governments to account for what we rely on them to do – deliver high-quality essential services, efficiently and fairly.

So what does one of these recent reports tell us about an area of activity that has enjoyed its share of policy and public attention in recent years – child protection?

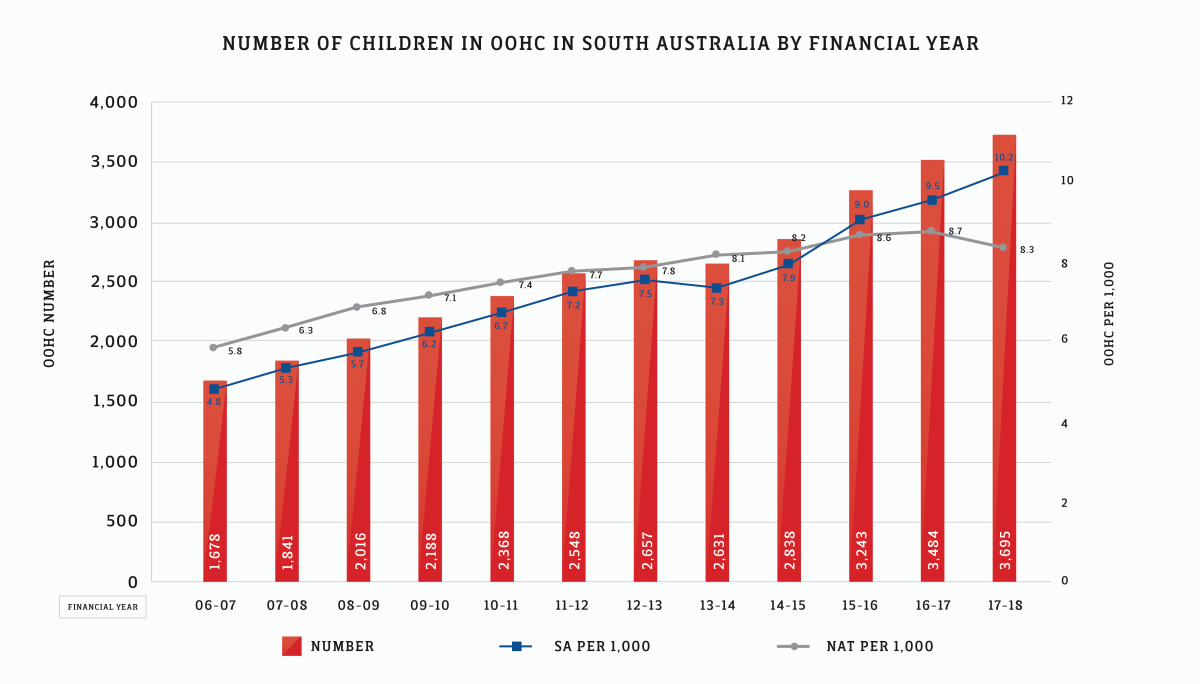

For a system that has had its critics, perhaps its best to start with the good or, at least, the better, news. While a change over one year clearly doesn’t constitute a trend, for the first time in more than two decades, the 2019 ROGS points to a real decline in the number of children and young people in Out-of-Home Care (OOHC) across Australia. It may have only been a modest reduction of just over 2000 children – and there are still 45,756 children in care across the nation – but it is clearly a move in the right direction.

The national reduction has been driven by two states – NSW and Victoria – with legislative reforms which, in part, have also impacted some of the counting rules. All other states and territories have continued an upward trend in having more children in care.

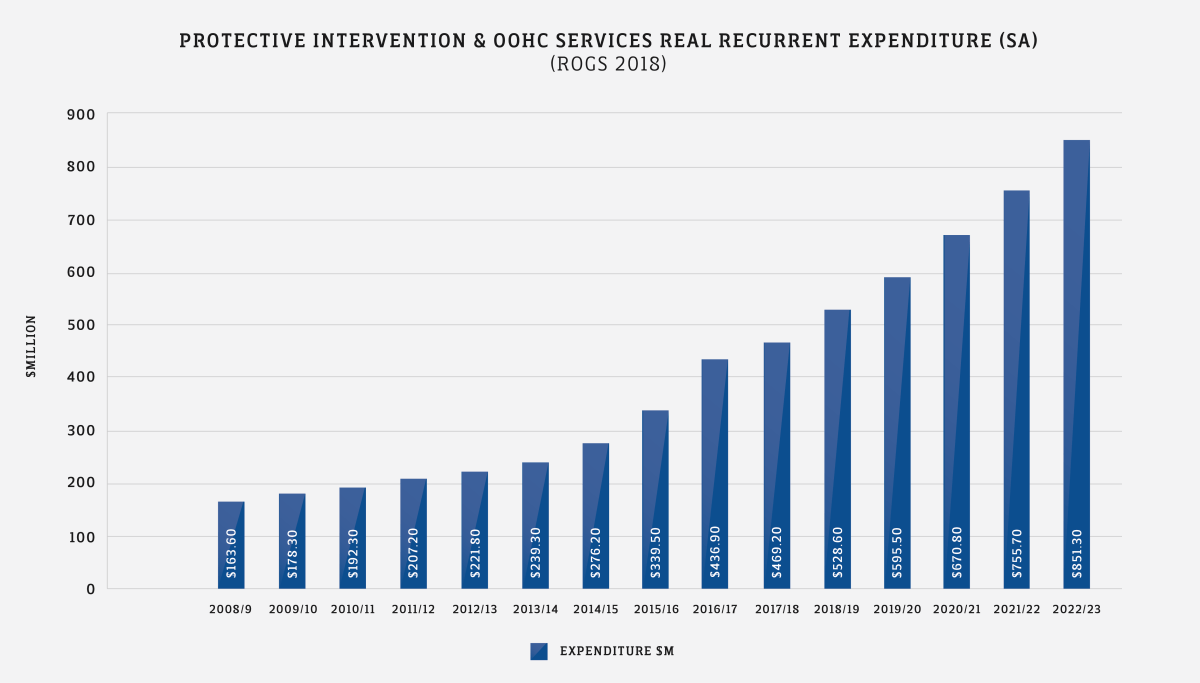

Although there has been an overall decrease in children living in care across the nation, the expenditure by governments on all forms of child protection intervention continues to climb at an alarming rate – more than 10 per cent in the past year.

Annual expenditure now totals just under $6 billion across Australia. More concerning is that this trend, which far outstrips our inflation rates, shows no signs of abating. It would be fair to say that as an area of public expenditure, it is getting seriously out of control for governments across the nation.

So what is the story for South Australia – a jurisdiction which has endured more than its own share of significant reforms in recent years?

To put a positive spin on the results, it is evident that South Australia may be beginning to put the brakes on what could best be described as an ‘expenditure explosion’ in recent years. Tracking expenditure on the two largest drivers of cost – the provision of OOHC and Protective Intervention – shows South Australia has stemmed the flow of the previous three years where budgets were blowing out by more than 22 per cent per annum. In the past 12 months, the increase was a more modest 7.4 per cent – albeit still adding a further $32.2 million to the budget.

This slowing of expenditure trends comes despite a real increase in the number of children and young people in OOHC in South Australia over the past 12-month period. While we added a further 211 children to care in 2017/18, we have managed to reduce our over-reliance on residential and emergency care. This makes a significant difference to the ‘bottom line’: the average cost of care of a child in residential care is more than $540,000 compared to just under $50,000 for home-based care.

South Australia still has a disproportionate number of children under the age of 12 in out-of-home placements – almost 10 per cent. While this compares to the national average of under 4 per cent, the figure has improved due to a decision by the government to reduce the unnecessary placement of children, particularly younger children, in residential or emergency care placements. This direction should be commended, in terms of delivering consistently better outcomes for most children at considerably less cost.

Notwithstanding this improvement resulting from clear policy choices and actions, South Australia continues to experience a major problem with the growing over-representation of children being removed, placed and staying in OOHC. Since the Nyland Royal Commission, the numbers of children in care have steadily increased, following a more than decade-long trend. Despite a royal commission and a host of subsequent reforms and expenditure, South Australia’s performance when it comes to the removal and retention of children in care continues to deteriorate.

- South Australia’s rate of children in care has increased by 112 per cent since 2006-2007. There are now 2017 more children in care today than in 2007.

- South Australia’s rate of 10.2 children per 1000 in care is significantly above the Australian average of 8.3 – unlike the national rate, the state figure is increasing not declining.

- On current trends, by the time of the next state election in 2022, there will be a further 900 children and young people in care than there are today – and we will be fast approaching an overall figure of 5000 children in care.

Clearly, the policy shift to reduce an over-reliance on residential care in South Australia is starting to deliver some positive improvement. This is expected to continue in the coming reporting periods as South Australia closes its larger residential facilities and aims to get closer to the national average on residential and emergency care use. These are policy failings of previous administrations and the current changes are welcome. So too has been the slowing in the over-representation rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) children across a key number of indicators including OOHC. However, with ATSI children still more than seven times more likely to be in care, there is significant room to move to address an over-representation that is adversely impacting too many ATSI children, families and communities.

However, these reforms will be nowhere near enough to get South Australia’s child protection system back on track. The rising number of children coming into and remaining in care needs to be addressed – urgently. This trend – now well entrenched for over a decade – must be turned around.

One area in which South Australia has scope to significantly improve is its reach of intensive family support services aimed at helping families and keeping children out of care or safely returned to living with their family. In the past year, only 1438 children benefitted from these interventions. This represents only a small number of eligible children and families who should be accessing these intensive programs. The rate of engagement of these programs is almost 30 per cent below the national average: the gap is even larger when compared to NSW and Victoria where many more families are able to access intensive support services. It is perhaps no coincidence that it is these two jurisdictions which have recorded the only real reduction in OOHC numbers in recent times.

One thing is for sure though for South Australia: doing more of the same won’t serve to reduce the numbers of children in out of home care. The South Australian government is seeking to establish a new strategy to enhance supports for families who need it most.

Looking at the statistics, it can’t come soon enough.

Simon Schrapel is chief executive of Uniting Communities.