An antidote for Australian cricket’s toxic masculinity

The toxic culture of Australia’s national cricket team has been exposed – but it’s been a long time coming. David Washington remembers a no-name team of the past that might provide a template for rediscovering what has been lost.

The baggy green tradition is not just macho chest-beating - it's also the tradition of Bradman and Simpson and Benaud. Photo: AP/Richard Lewis

Cricket became my obsession over the magical summer of 1977/78 – an Indian tour of Australia that should have been a low ebb for our national team.

After the triumph of the Centenary Test at the MCG – a one-off match against England, won by the home team but only after the Poms gave us an almighty scare – Australian cricket fragmented.

Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket “circus” – as it was called by the establishment – whisked away the majority of Australia’s best players.

With Chappell, Marsh, Lillee and other legends putting on a colourful display on commercial TV, Australia’s monochromatic official Test team was – by and large – a second-tier outfit, covered by the archaic traditions of ABC television.

Bob Simpson, a serious, dapper and long-retired former captain, was brought back to the captaincy at the age of 41, to attempt to compete against the Indian tourists, led by the clever spinner Bishan Bedi. [Later, Simpson said he was prompted to return by his conviction that an entrepreneur should never run a sport.]

Simpson’s team included a range of players now forgotten by many cricket fans, and only a few established players, most notably tearaway fast bowler Jeff Thomson.

The series, to my 10-year-old eyes, was captivating, even through the bug-eyed lens of an ancient black-and-white Astor television.

It is widely remembered for the good grace with which it was played, despite the intense closeness of the on-field battle. None of the five Tests was drawn, with Australia securing a 3-2 victory on the final day of the final Test in Sydney.

My first fascination was with Simpson, who came out of a 10-year retirement to lead the team. Could he still play? How did he play? I was a baby when he’d last played cricket. To me, he was like an apparition from another era – as if he’d stepped out of one of the legendary Bradman teams of the ‘30s and ‘40s. He was impeccably turned out, his black hair slicked back, and played the wily Indian spinners with a deft touch.

My favourite Australian was young middle-order batsman Peter Toohey – a light-on-his-feet player who scored freely in that series, but never cracked the century. Toohey also appealed because he was a fighter – his best innings played when Australia had its back to the wall.

Bedi, too, was intriguing to watch, the turbanned captain bending the ball through the air and spinning it off the pitch, even in bouncy Perth.

Perhaps some of the magic of that series was the collection of no-name players gathered around Simpson. If these young fellas I’d never heard of could play for Australia, why couldn’t I?

In contrast to the bombast of the Chappell-led Australians, this Simpson team was marked by what cricket writers remember as quiet dignity.

They knew they weren’t the best players in the country: but they took the opportunity with grace and respect for the traditions of the game. They knew that, in cricketing terms, this was their moment in the sun; for many in the team, this was likely to be their career high-point and they wanted to be remembered in the best possible light.

For a kid like me, being able to flick between the big-name flash of World Series Cricket and the more subtle joys of the officially sanctioned team was something I have never forgotten.

The behaviour of Simpson’s team also spoke something to me as an Australian boy who was dubbed “Boycott” on the primary school cricket field because of my love for sound defence (and, probably more honestly, my incapacity to play big shots).

The message was that there is masculine honour in the quieter aspects of athletic achievement. While it was understandable to want to be Dennis Lillee, nostrils-flaring, shirt open, chest hairs waving in the sun, it was also acceptable to want to be a Bob Simpson – well-dressed, thoughtful, a disciple of carefully-planned strategy and hard work.

Simpson took the make-shift Australians on a less successful tour to the West Indies in 1978, which nonetheless kept the national team’s dignity intact.

Toohey hit the peak of his 15-match Test career on that tour, hitting 122 and 97 in the Jamaica Test – an incredible comeback after being hit in the face on a wet pitch by an Andy Roberts bouncer earlier in the tour (Toohey was stitched up and returned to bat later in the innings).

Years later he talked about the joys of his brief career – what it meant to all of his teammates. “We were all excited, nearly all debutants, it was a big deal to us.”

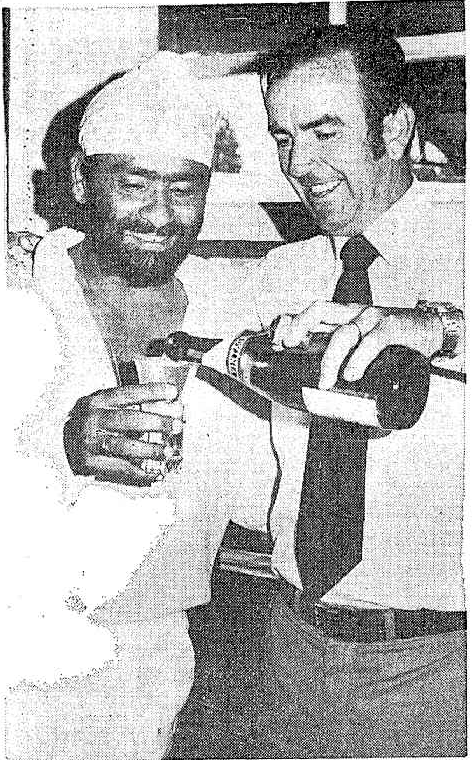

A newspaper shot in 1977 of Bob Simpson pouring champagne for his Indian counterpart Bishan Bedi. Simpson’s Australians had just lost a Test.

Toohey’s pleasure in playing strikes me as a shocking contrast to the entitlement, the born-to-rule, win-at-all-costs attitude of contemporary national teams, many of whom have made Australian cricket supporters, myself included, cringe even as they were becoming one of the most dominant teams in history.

Even in the years immediately following the 1977-78 series, when the Chappells, Lillee and Marsh were back in the fold, I had a sense something had changed – that playing was no longer a pure joy for those at the top, that winning was more important than anything – that it was, indeed, bigger than the game itself.

After the slump of the 1980s, when Australian teams struggled terribly, the national team entered a golden era – at least in terms of winning. They became more successful, more dominant – and increasingly boorish.

And today, with the team again struggling to reach the top, we have reached an apotheosis of this culture, which has all the traits of toxic masculinity.

It’s a culture replete with typically Australian macho bullshit: celebrations of mammoth drinking sessions on the plane to England; an insistence that players sit for hours in the dressing room after a win watching their “mates” get pissed, instead of being able to leave and see their families; the celebration of pathetic sledges against hapless opponents; puffed-chest posturing and screaming after dismissals. [This, of course, is an aggressive culture not limited to sport: we see it increasingly in politics, business, the media and public debate more generally.]

The superficial nature of the culture underpinning our national team has finally come crashing down, after the team’s current leaders deemed it appropriate to cheat – and to allow a younger player to carry out the dirty work. And isn’t that kind of pressure familiar to every Australian male who has been burnt by the national mythology of acceptable manhood?

But we should remember that it hasn’t always been like this – it doesn’t have to be like this. There has always been another element in Australian sporting culture: the properness, some would say stiffness, of Don Bradman (for which he has been pilloried), the class and humility of Ken Rosewall, the astounding sportsmanship of John Landy, and the pluck and good grace of Bobby Simpson’s makeshift team of 1977/78.

Some good can come out of the ball tampering scandal, but only if firm action is taken to transform the team’s culture and replace its leadership with people of character who value and reflect Australia’s deeper cricket traditions.

Maybe then our cricket team can once again become one of which we can be proud – whether they win or lose.

David Washington is editor of InDaily.