Confronting the voter turnout challenge for SA’s Voice elections

South Australia’s inaugural First Nations Voice elections present a unique voter turnout challenge for the Electoral Commission and a test of the state’s civic institutions.

A man on his way to vote at a First Nations Voice mobile polling station in the Aboriginal community of Yalata. Photo: Thomas Kelsall/InDaily

Two hours west of Ceduna along the Eyre Highway lies the remote community of Yalata: a dusty and dry locality spread across 34 hectares – roughly the size of Adelaide’s Botanic Park – that houses a transient population of about 350 people.

On March 6, a small cream-coloured building has been adapted into a makeshift polling booth.

The Electoral Commission established the booth that morning to give the Anangu community in Yalata the chance to vote in the inaugural SA First Nations Voice elections.

But in the first hour, there are few people around the polling station.

The mobile polling booth in Yalata on March 6. Photo: Thomas Kelsall/InDaily

Voter turnout and engagement is a challenge the Electoral Commission is confronting with the Voice elections. On top of this, the Commission is also trying to explain to voters the difference between the South Australian Voice and the federal Voice which was defeated at the October 2023 referendum.

More than 100 First Nations candidates have nominated to be on one of six local Voices. A full explanation of the South Australian Voice can be found here.

In Yalata, the situation improves as the day progresses and a trickle of prospective voters begin walking to the polling booth after 10am.

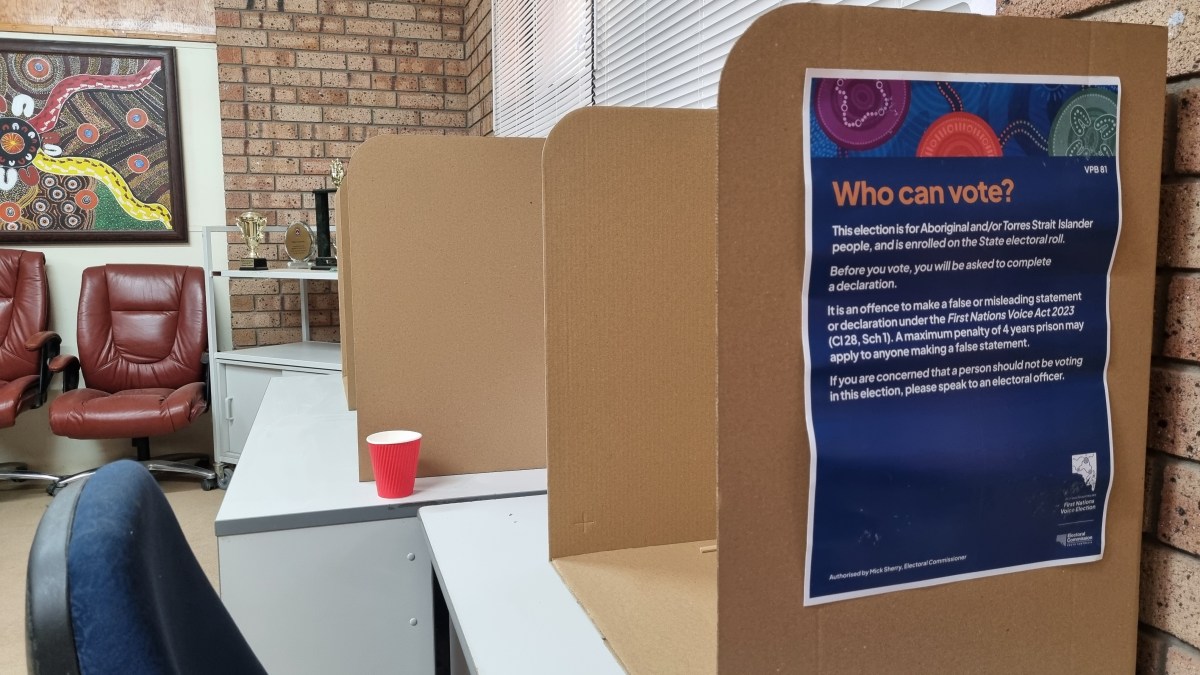

Inside, they are asked all the standard questions in an election (what’s your name, have you voted before) along with a new, unique requirement to sign a declaration confirming they are a First Nations person.

Insider the Yalata mobile polling place. Photo: Thomas Kelsall/InDaily

Ngarrindjeri man Lawrence Sumner was one of the first to cast his vote in Yalata that day.

He told InDaily after the vote that he had heard “bits and pieces” about the Voice but “no one’s come up to me and tell me about it yet”.

“I’m still learning about it at the moment,” he said, “I’m not 100 per cent what it’s all about.”

“The Voice is just to get things happening and going for Aboriginal people.”

Sumner is an Aboriginal family support worker who has worked in Yalata for the last nine months.

“I go around people’s houses and that and make sure they’re okay, if they need doctors’ appointments, medical appointments, washing machines, brooms,” he said.

“Just going around and seeing if they need a hand and… help them get it.”

Sumner believes politicians don’t listen to Aboriginal people – “if they did, it would have changed years ago” – but is hopeful the Voice will bring change.

He’s also confident some of the candidates he’s met for the West and West Coast region will “put their point straight out [about] what we need around the community and South Australia”.

“I just need someone to get the voice out and tell them what we really want and make this community a bit more stronger,” he said.

Setting up the mobile polling place at the Yalata Community Hub in Yalata. Photo: Thomas Kelsall/InDaily

Asked what he made of the federal referendum result, Sumner said: “I’m still learning what was Yes for and what was No for.”

“Was it Yes to change the constitution or was it No to keep it? So I was a bit lost there.”

West and West Coast region candidate Rebecca Miller, an Aboriginal education worker in Port Lincoln, is also acutely aware of the voter awareness challenge.

She said she is campaigning over social media but community awareness about what she’s running for is “quite minimal”.

“I did a Snapchat blast last weekend, probably 85 per cent that snapped me back asked ‘what is this for?’,” Miller said.

“With the responses that I got on Snapchat, a lot of people – so these are younger people in the community – aren’t enrolled to vote.”

There are around 30,000 First Nations people in South Australia eligible to vote in the Voice elections, according to the Commission. The voting roll closed on February 12.

Voting is not compulsory, and turnout will be closely watched with the Voice under political scrutiny from the Liberal Party and One Nation MLC Sarah Game (the latter has vowed to repeal the State Voice).

Sign marking the entry to Yalata. Photo: Thomas Kelsall/InDaily

The Electoral Commission has not set a target for turnout in the inaugural Voice elections, according to the Commission’s communications director James Trebilcock.

Trebilcock also conceded that it has been “challenging” to have the Voice election only five months after the federal referendum, but said one-to-one conversations have been helpful in communicating the difference.

“One of the things that we have found by engaging with the communities and engaging with them one-to-one is that once we sit down and explain everything to them, the community actually really gets engaged with the South Australian Voice election,” he said.

“It’s been a really good process for us to be able to get out and talk to those people and explain to them what’s going on but also talk to them about any worries they have as well.”

Aboriginal voter turnout is generally much lower than non-Aboriginal turnout in national and state elections, according to Dr Rob Manwaring, associate professor at Flinders University’s College of Business, Government and Law.

But Manwaring said the novelty of the first Voice elections could drive more people to the polls.

“National elections will always get higher turnout than local or smaller elections,” he said.

“But where something is kind of quite specific in terms of particular communities eligible to vote, you might see much more increased areas of people turning out.

“I think there’s going to be a lot of interest in this… and I think turnout should be particularly good in certain areas.”

Manwaring added that “the rest of the nation is looking to see how this plays out” and there is “hope resting that this works really well and contributes to a new part of South Australia’s civic institutions”.

But he cautioned that the Voice could suffer from the “halo effect” whereby a strong turnout in the first year “wears off over time” and is not repeated when the second Voice elections come around in 2026.

“The first time a phenomenon happens there tends to be a lot of interest and excitement… and people think we can replicate that again,” he said.

“If Indigenous South Australians increasingly feel the Voice Is not making a big meaningful policy outcome, then it might be harder and harder over time to drive up enrolment.”

Polling day for the Voice is this Saturday, March 16. The results will be declared on March 25.