Don Dunstan, the cops and Adelaide’s ‘street crime’ anxieties

As Adelaide once again worries over ‘anti-social’ behaviour on the streets, Simon Royal delves into the little-told history of a crime scare in Norwood that enveloped police, a young politician called Don Dunstan, an Olympic gold medallist and a generation of “new Australians”.

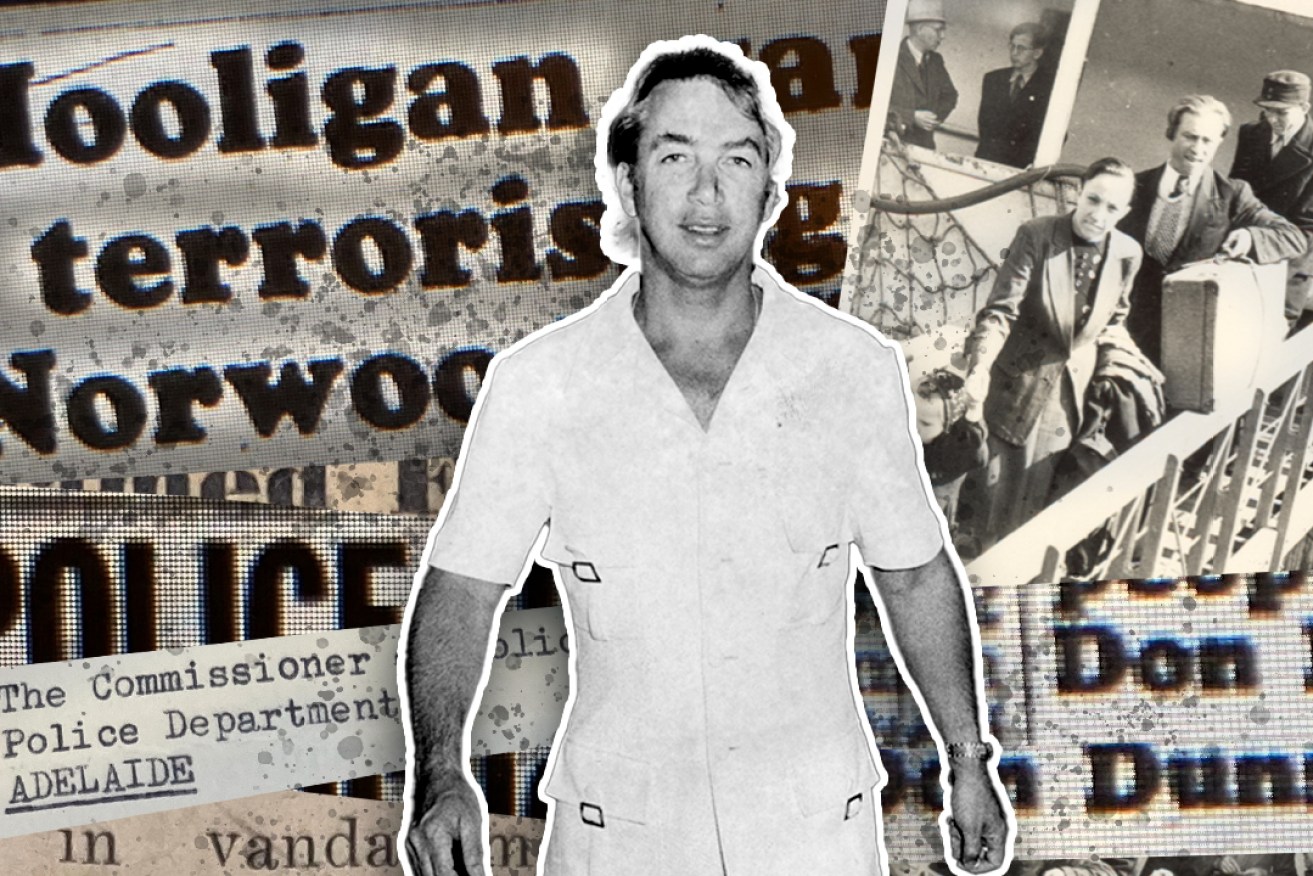

Few phrases are more instantly evocative to South Australians than, “The Dunstan Decade”. Simply hearing or reading it is enough to ‘see’ the garish magnificence of the ’70s again: the safari-suited premier, striding the state stage, orchestrating a swirl of long overdue reforms to a once deadly dull place.

It’s become a cipher, or maybe a cliche, explaining both Dunstan’s career and how we live now – sitting in bars, leisurely sipping wine or coffee, before heading out for a meal. Pity our poor forebears, desperately guzzling beer before 6 o’clock closing, then trudging home to overcooked meat and three veg.

Our Adelaide is a cosmopolitan city. Theirs was a grim village.

Dunstan was the architect of the transformation, inspired in large part by the “cafe, coffee, and chianti” lifestyles brought to Norwood by his Italian constituents. But like many catchphrases, “The Dunstan Decade” informs and obscures at the same time.

The 35th premier’s time in office was defined by life-changing reforms, along with some equally deep conflicts. The latter are less discernible from this distance, but important all the same.

Furthermore, if it’s not shocking enough for younger readers to learn pubs once closed at 6pm, the most significant of Dunstan’s conflicts weren’t so much with his political rivals, but with the state’s senior police.

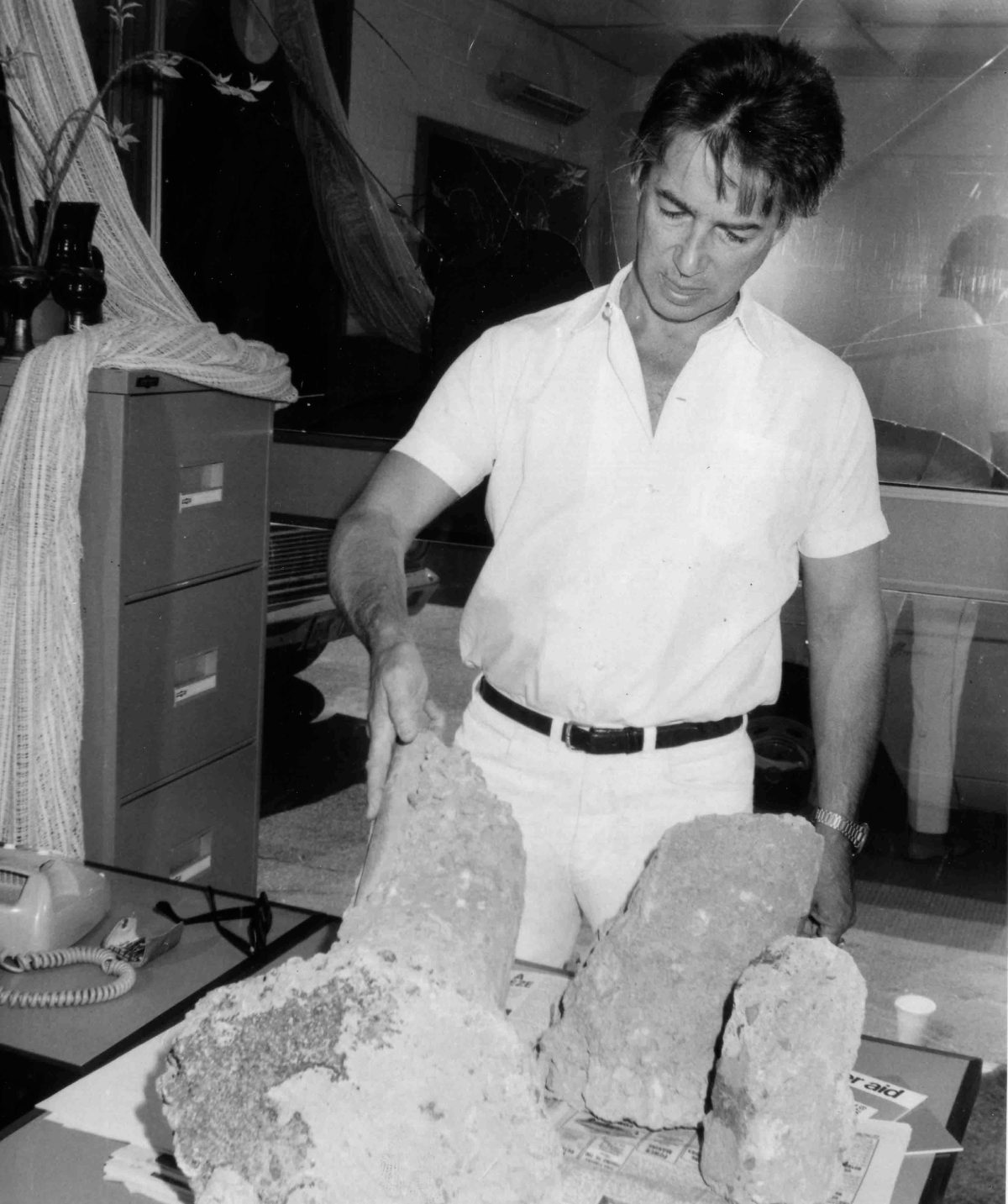

Don Dunstan in his Norwood electoral office in the late 1970s, with chunks of concrete that had been thrown through the windows.

A well-mannered relationship between top coppers and premiers is a feature of our time, not Dunstan’s. The most spectacular clash was the Salisbury Affair of 1978, when Don Dunstan sacked Harold Salisbury – the man he’d hand-picked as police commissioner, a few years earlier. For decades, police kept secret files on the private lives of everyday South Australians. Dunstan said Salisbury deceived him about the existence and nature of those files. Some of Dunstan’s contemporaries argue the backlash over Salisbury’s dismissal was the beginning of the end for his government. If that’s correct, then it’s an example of things finishing in the fashion they commenced.

The 1970s, and the Dunstan government, were only a few months old when the premier had a heated public spat with Salisbury’s predecessor, Commissioner John McKinna. The premier and the policeman were at odds over the anti-Vietnam War protests sweeping the nation. Dunstan urged police restraint; McKinna preferred a meticulous adherence to the law.

Amidst shouting and violence in the streets, 141 people were arrested during the September 1970 protest. In Melbourne, where Victorian police faced a much larger crowd, four arrests were made. But Dunstan’s occasionally fractious relationship with senior police has an even longer history. The state archives reveal animosities predating Vietnam and Salisbury – the foundations being laid when Dunstan was an aspiring MP.

Anxiety and the changing face of Norwood

At the start of 1950, the Mayor of Norwood, Ron Moir, decided he’d had enough. He and his fellow councillors felt their township was becoming a little less familiar each day: more young people, more migrants from unpronounceable places, more trouble on the streets, and, most disturbingly, fewer police dealing with it all. After some names and initials were scratched into a freshly painted building, Moir decided a robust story in The Advertiser might prod authorities to combat the menace. The next day an article appeared with the headline, “Police Shortage Blamed For Vandalism”.

“A serious position is existing in the town due to a lack of police protection,” Moir told the paper. “ I have had complaints that there are no men on duty in the Parade… there is increasing larrikinism in the town.”

According to Moir, one reason for the shortage was that officers were being diverted into practice sessions for the police band – too much keeping the beat, rather than policing it, for the mayor’s liking. As it turned out Moir didn’t get his extra police, but his story did leave a legacy of sorts. Someone from police headquarters clipped the article out of The Advertiser’s page 4, and awkwardly stuck it to a sheet of A4. This started a brand new PCO file – correspondence to and from the Police Commissioner’s Office. Designated 13036 GRG5/2, the file grew to be a great fat thing. It runs from 1950 to 1961, scooping up further council complaints about inadequate policing in 1955, ’56, ’57, ’60 and ’61.

On one occasion, the council primly noted, “[a] shopkeeper being subjected to the unnecessary attention of two New Australians on Saturday night”. The public loos had also been blocked with toilet paper. There was a great deal of concern about Italian youths congregating, and “fighting on the Parade between New Australians and others…”

Making liberal use of the state’s very illiberal anti-loitering laws, police routinely moved these young people on but not before recording their names: Filosi, Gasparini, Fantasia, etcetera, plus a smattering of so-called “Australian” sounding names, such as Bishop, Bevan, and Carter.

Superficially, it’s a file of parish pump worries about petty crime and police staffing. But 13036 GRG5/2 is really an insight into the growing pains of multicultural South Australia. As always, conflict plays valet to change.

This emerging new place, with its new people, was to become the backdrop to maybe the earliest Dunstan/McKinna clash.

The media strategy

One January afternoon in 1956, Don Dunstan was driving down the Parade when he saw some teenagers gathering outside a milk bar. For more than a week, ugly brawls had broken between, as police put it, “Italian youths and Australians”. The first term member for Norwood cut to the kerb, parking his car in front of another vehicle. He didn’t seem to notice the man inside, also watching the scene.

Looking not much older than the milk bar kids himself, Dunstan hurried across the road. He was keen to hear directly from the youngsters about the fights. The fact the state election was less than two months away, no doubt, added to the urgency. Dunstan and the teenagers had barely exchanged a few words when police from Adelaide arrived, moving the young people on. The MP was left alone, but not for long.

Migrants seeking a new life in South Australia. Photo courtesy the Migration Museum

The man from the other car came over. His surname was Fry. He was the officer in charge at Norwood police station, and he wanted to talk about the recent fights. Repeating the council’s long-standing complaint, Fry told Dunstan that Norwood was understaffed for the job at hand, to which the MP replied: “Well, something will have to be done to get you assistance.”

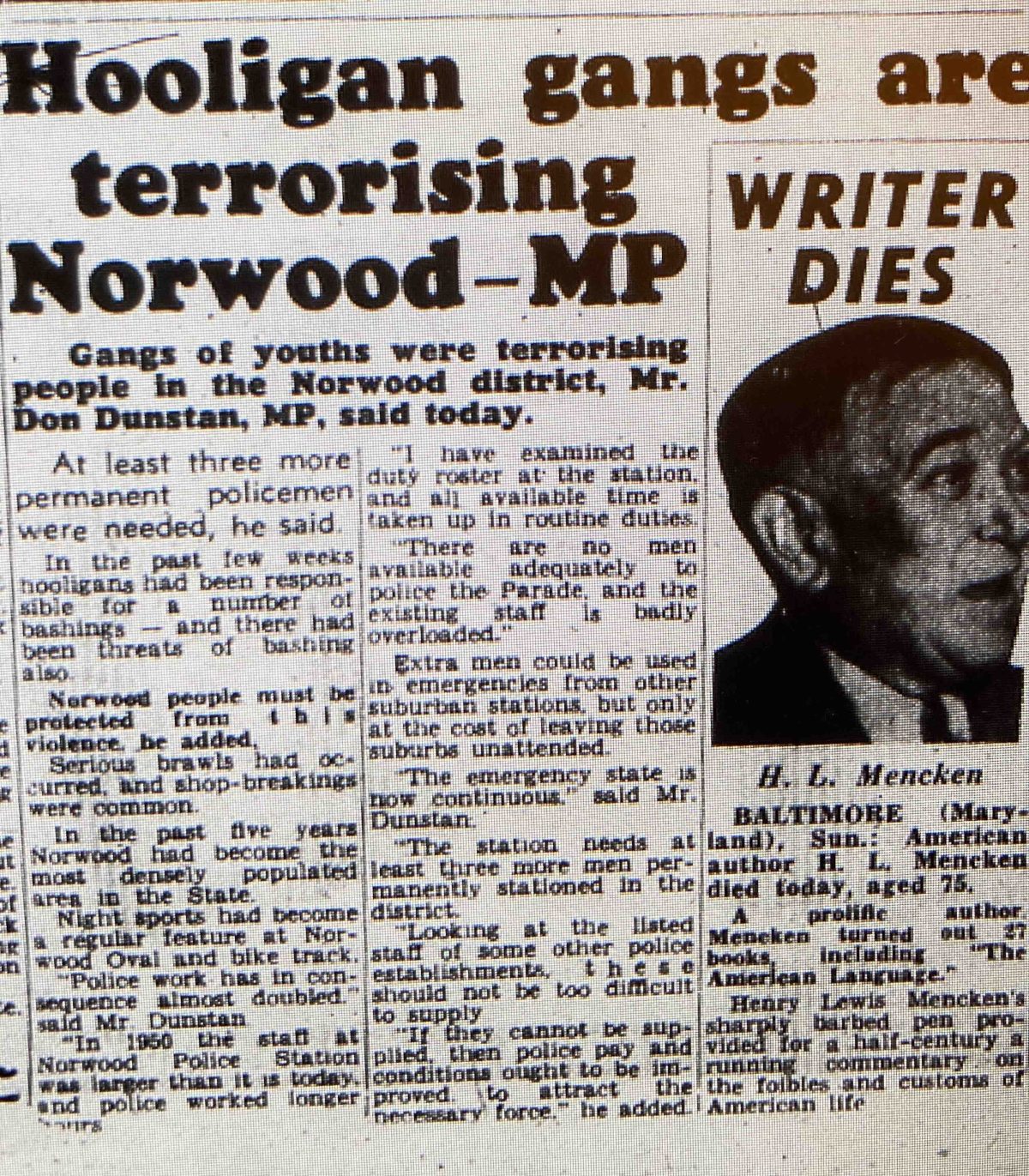

Later, Dunstan dropped by the station, asking Sergeant Fry if he might look through the duty roster. The policeman readily agreed. Whether Fry knew or not of Dunstan’s master plan isn’t clear, but one suspects he did. Either way, a few days later the headline blasted out from The News: “Hooligan gangs are terrorising Norwood – MP”.

Dunstan claimed bashings, shop breakings, and threats were commonplace. “Norwood people must be protected from this violence”, their local member said, before adding dramatically, “the emergency state is now continuous.” Today that use of ‘streets of fear’ language by someone like Don Dunstan is frankly shocking. Back then, it wasn’t Dunstan’s intemperate language that annoyed senior police, so much as one of their own enabling an ambitious politician to publicly embarrass them.

“In 1950 the staff at Norwood Police Station was larger than it is today,” Dunstan told The News. “I’ve looked at the duty roster… existing staff is badly overloaded… the station needs at least three more men.”

Having roused the bear, Dunstan decided he may as well poke it. He said the books showed plenty of staff in other stations available for transfer. If that didn’t work, “then police pay and conditions ought to be improved to attract the necessary force.”

Fry and Dunstan’s foray into print did indeed provoke a speedy response: the same afternoon the article appeared, the sergeant was ordered to write his own report to explain his actions.

The blame game

Over two-and-a-half tightly spaced pages, Fry produced a blend of sweet naivety and quiet boldness: part lament, part defence, part uncomfortable truth from the coalface. Fry wrote he’d let Dunstan peruse the books because, “as a Member of Parliament and sitting member for the district I could not see what authority I had, if any, not show him… the time book and duty roster. Mr Dunstan has been trying to assist the Norwood Police in every way that he can do so.”

The sergeant then detailed a litany of recent events in Norwood, followed by a forthright, (or foolhardy) observation about the lack of resources. “I have repeatedly asked for assistance,” Fry wrote, adding that he worked 11 to 12-hour days. “Practically all persons in the district know there is seldom a Policeman on the beat during the afternoon and evening… it is through lack of supervision that these brawls and acts of hooliganism are now taking place.”

Fry blamed migrants for causing much of the trouble. “Practically every time an Italian is stopped and questioned he puts on the ‘No speak English, No understand,’” the sergeant wrote. “It is impossible to do anything with them without the assistance of an interpreter.”

Dunstan certainly did not share that view, nor for that matter did every single police officer. But according to Greg Crafter, who succeeded Dunstan as Norwood’s Labor member, Fry’s attitude broadly reflected the era.

Dunstan certainly did not share that view, nor for that matter did every single police officer. But according to Greg Crafter, who succeeded Dunstan as Norwood’s Labor member, Fry’s attitude broadly reflected the era.

“There was a lot of intolerance of people who didn’t speak English, or speak it well,” Crafter says. “I remember from my growing up, dances at the Norwood Town Hall were notorious. Girls would refuse to dance with boys who had ‘European’ sounding surnames… we hadn’t really grasped that people could be different, and yet also right.”

But Sergeant Fry had a few other ideas which aren’t so jarring today. The Norwood policeman wasn’t merely cultivating his local MP to fight for resources. Despite his distaste for the newcomers, Sergeant Fry also knew his job could be done better if he used Dunstan’s links to them. His report chided the cack-handed interference of his Adelaide colleagues for wasting that opportunity.

“[They] gave Mr Dunstan no chance to get the information he sought. It is with the knowledge of the fights and brawls and the impossibility …to cope with the situation that prompted Mr Dunstan.”

Norwood would eventually get extra police attention, though whether Fry and Dunstan had any influence isn’t obvious. The only written response to the sergeant’s report was a curt summary of allowing Dunstan look at the books: “Sergeant Fry acted with [a] lack of prudence, ” his superior wrote.

One would have expected the matter, and the sergeant’s career, to have rested there. And it did, for a while at least. But in 1961, Dunstan reignited the controversy surrounding his meeting with Sergeant Fry. Much of the impetus for his doing so came after an Olympic champion drove down Norwood Parade, straight into her own unfortunate encounter with police.

Gold-medal arrest

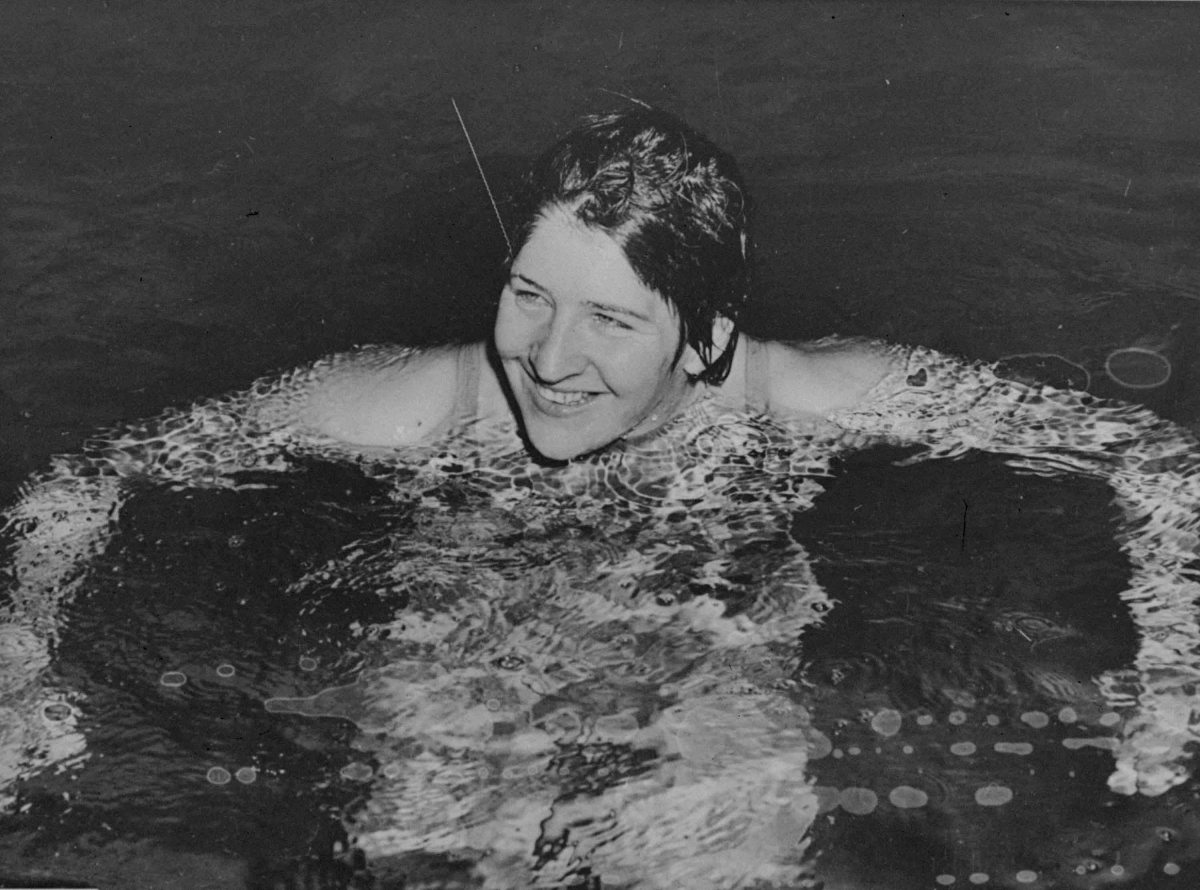

It hadn’t been the best 12 months for Dawn Fraser. Australian swimming officials had just released a scathing critique of the swimmer’s conduct at the Rome Olympics. Not that the public gave two hoots – they adored her. Things weren’t great on the home front, either. Fraser’s training schedule required her in Adelaide, while her father back in Sydney was terribly ill.

Still, no one expected to read the news that the star Olympian had been arrested at 12.30 on a Sunday morning, before being bundled off to a police cell. Fraser faced court, where a charge of loitering was hastily dropped. Despite a concession that Dawn Fraser had done nothing wrong, the prosecutor insisted police “were fully justified in their action”. This bizarre stance only deepened the gracelessness of the apology offered to Fraser for any inconvenience, “if any has been caused”.

Sniffing out a better story than had come to light in court, The Bulletin magazine interviewed Fraser’s coach, uncovering what had really happened.

Dawn Fraser in October 1962 after setting a new world record time in the 100-metre freestyle in Melbourne. Photo: AP/Melbourne Herald

“The swimmer was driving back in a friend’s car from the annual ball staged by the department store she works for, and asked him to drop her outside a Norwood Parade coffee shop, where some friends were waiting,” The Bulletin reported in May 1961.

“The car pulled up with a squeal of brakes, which led two young constables to question the driver. What was said is not known, but Miss Fraser was ordered to move on. When she told them she was going into the coffee shop, they arrested her for ‘loitering’. This was done under a law peculiar to South Australia. In other states, police have to prove loitering with intent.” The Bulletin also noted: “Adelaide has not heard the last of the Fraser affair. Labor M.P. Don Dunstan… says he will call for a full report when Parliament meets…”

Dunstan got to his feet in parliament on August 2, 1961, using the still raw national embarrassment of Dawn Fraser’s arrest to great effect. Miss Fraser was “grievously mistreated”, he said, arguing the swimmer was part of a disturbing, long-running pattern. Dunstan told the house that some police regularly abused the state’s loitering laws. They not only moved people on without any cause, but would stubbornly insist on the path by which they should leave. Carefully re-iterating his support for Norwood’s local officers – “they certainly would not have been involved in a thing of this kind”- Dunstan described the recent experience of three Italian constituents. The men were talking shop outside a corner deli, when they were confronted by angry, shouting policemen. Dunstan told his fellow MPs that one officer shone a torch in the men’s faces, ordering them to leave immediately. Threats of violence were made to the men if they didn’t comply.

The member for Norwood then recounted his meeting with Sergeant Fry. Naturally, Dunstan treated parliament to a far more vivid account than the one Fry offered his bosses five years earlier. In Dunstan’s version, he and Sergeant Fry made a prior arrangement to meet the youngsters outside the milk bar. They went there together. It was all perfectly reasonable, until the Adelaide crew arrived.

“A police patrol car not from my district came screaming down The Parade,” Dunstan said. “Constables got out of it and they ordered, with a loud shout, everybody to move away from the place or they would be arrested there. The boys talking to me, according to the arrangements I made with the sergeant, melted out of sight on their bicycles.”

Dunstan said he, too, was ordered to move on, until he was recognised. But a couple of over-eager constables weren’t the main target of the speech. It was Police Commissioner, Brigadier John McKinna, whom Dunstan suggested condoned the widespread abuse of loitering laws.

This time the story wasn’t a one-day wonder. The Advertiser reported Dunstan’s remarks, (oddly minus the Fraser story) with the headline, “Police Patrols Criticised”. For close to a fortnight, interspersed between news of the rise of the Berlin Wall, and reports of John Martin’s sparkling new bank of escalators,(Australia’s largest), The Advertiser ran letters to the editor. Virtually all were critical of Dunstan, and they are dutifully included in 13036 GRG 5/2. Also on file are a pair of letters never intended for publication. They, too, are hostile to the member for Norwood.

Mayor Moir was long gone, but Norwood council remained as vexed as ever by hooliganism and vandalism. Curiously though, the organisation seemed unfazed by the publicity of the Fraser affair, and Dunstan’s claims of residents being harassed by police: neither was mentioned in a letter the Town Clerk sent to Commissioner McKinna.

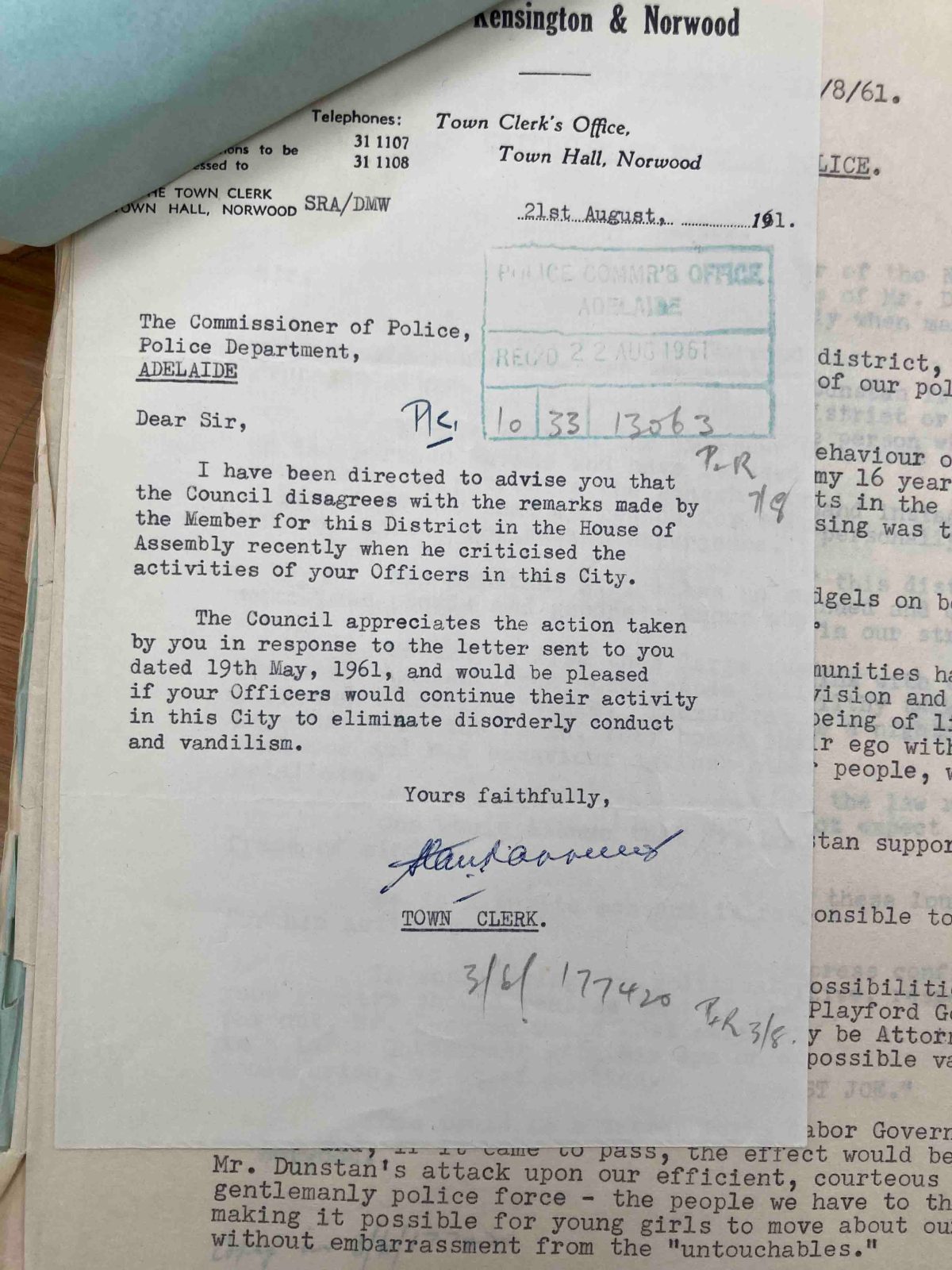

“I have directed to advise you that the Council disagrees with the remarks made by the Member for this District … when he criticised the activities of your officers in this City,” the clerk wrote on August 2. “[We] would be pleased if your Officers would continue their activity in this City to eliminate disorderly conduct and vandilism (sic).”

Despite ushering in cafes, coffee, and Chianti, being a migrant in 1950s Norwood was neither all beer and skittles, nor all la dolce vita.

A few days later McKinna replied, thanking the council for their letter, “which I greatly appreciate.” Dunstan isn’t named in McKinna’s letter, but his presence is unmistakable.

“Unfortunately there is today, in some quarters, an excessive anxiety for the welfare of the wrong-doer, with little thought being given to the rights and safety of law-abiding citizens,” the Commissioner wrote, arguing that, left unchecked, larrikins and vandals “could soon destroy the concept of individual liberty…” With that flourish of unintended irony, and an assurance of business as usual, the commissioner concluded his letter. The exchange is the last entry into 13036 GRG 5/2. But while the file was done, the attitudes and relationships expressed within were only beginning to play out.

It’s a fair bet neither John McKinna nor Don Dunstan cared much for one another personally, which subsequently coloured their professional relationship. They were starkly different people.

McKinna was a little boy during the first world war and a young man in uniform during the second. A disciplined, decisive man, Brigadier McKinna’s rise up the ranks came largely through the military, rather than the police. After commanding soldiers on the front line, McKinna went into business. It was only in 1956, just shy of his 50th birthday, that John McKinna became a policeman, sitting immediately in the Deputy Commissioner’s office. Dunstan was a generation younger, being born in 1926. He was educated at St Peter’s College, studied law at the University of Adelaide, and adored the arts. Dunstan preferred bards to brigadiers and boardrooms.

There are, however, some important things neither man would admit to – the ways in which they were alike. Greg Crafter explains, “…they were both strong personalities, that’s true. They both held important positions, and they really stood their ground on each other.”

That ground was the law, which each man was devoted to serving. At war, McKinna learned following orders was a matter of survival. Experience and temperament taught him the law worked best when it, and the police officer laying it down, were obeyed without question. After McKinna’s death in 2000, the police journal’s obituary made particular mention of one achievement.

“He [McKinna] is still remembered for forming SA’s Anti-Larrikin Squad in 1958. The squad enjoyed unparalleled success dealing with the hooliganism of the Bodgie – Widgie cult.”

Norwood was a major focus of the squad’s work. In a telling moment during his loitering laws speech, Don Dunstan was interrupted with a question: “Would this be the anti-delinquent squad?”

Given his long relationship with Norwood police, and his knowledge of the district, Dunstan’s reply was unconvincing: “I don’t know.”

Given his long relationship with Norwood police, and his knowledge of the district, Dunstan’s reply was unconvincing: “I don’t know.”

John McKinna was not a bad man, and far from being a poor police commissioner. But his behind-the-scenes letter to Norwood council – slagging off one politician to a bunch of others – was not his finest moment. We can, though, now understand why he chose to write it.

Dunstan also believed the law should be followed. But his experience and temperament had taught him to value where good laws might lead. For many Italian migrants and other outsiders, the rules and ways of 1950s Norwood were too often a road to arbitrary injustice. Despite ushering in cafes, coffee, and Chianti, being a migrant in 1950s Norwood was neither all beer and skittles, nor all la dolce vita. The bitter experiences, from abuses of loitering laws, to everyday acts discrimination, were just as crucial in setting up the Dunstan Decade.

“I learned that soon after I became the local member in 1979,” Greg Crafter recalls, while downing a flat white on Norwood Parade. “Many of the older Italian people I’d door knock would talk about how they’d told Don about their troubles with dodgy car salesmen and second-hand cars …and other events like that. They were behind him as Premier introducing reforms, such as the ones we made to consumer laws, just as one example.”

Tempting though it is to imbue Don Dunstan and Sergeant Fry’s meeting with some sense of great historic mission, it would be rubbish to do so. In that moment, all the pollie and the policeman wanted was a solution to a perceived problem – finding enough warm bodies in uniform to stop fights on Norwood Parade.

Nevertheless, beyond the practical, there’s always room for a little romantic reflection. On a summer afternoon nearly 70 years ago, Don Dunstan and Sergeant Fry could see that the world had changed. Their shared desire to respond to that reality, rather than the past, was a small step to where we are now.