Running the Ropes: behind the tough facade of Adelaide’s pro-wrestlers

In the final part of a series in which Angela Skujins dived into an art form based on equal parts theatre, bloodlust and physical pain, she learns how it can transform members’ lives both inside the ring, and out.

Hippocrates said: “Make a habit of two things —to help, or at least to do no harm.” Although the Greek physician said this in the context of medicine, it’s applicable to professional wrestling in South Australia.

Lachie Watts, our coach and ring master for the evening, tells a gym full of wrestlers at Riot City Wrestling (RCW): “Your body is a temple.”

“We often do this for little return,” he adds, gesturing to the ring. He leans back on the ropes and adds: “We get beat up, thrown around, pummelled, and sometimes we get paid for it, but most of the times we don’t.”

It’s the end of the night’s session. Lachie stands up and looks at the wrestlers earnestly. He says to them – some grimacing from pain, others smiling: “Be kind to yourself.”

Lachie gives this sermon during my last training session with RCW. After weeks of immersing myself in the independent professional wrestling community – I trained, thought, and marketed myself like the other athletic Leviathans – it was time to hang up the overacting and fake-outs.

But this idea of being kind to yourself and helping others in this hyper-masculine world stayed with me. Is compassion a necessary ingredient to survive the barbarity of what is at the core of professional wrestling?

A professional wrestler, the 30-year-old Jack Styles, who runs with the moniker Jensen Hunt, embodies the braggadocio spirit that bleeds through any great wrestling performance. He also has the physical aptitude to flatten a man like a sledgehammer. His appearance back it up – he’s got thick mutton chops, and enough chest hair to weave a small blanket. But a tattoo on his bulging bicep, “Even through the darkest days this fire burns always,” hints at something underneath.

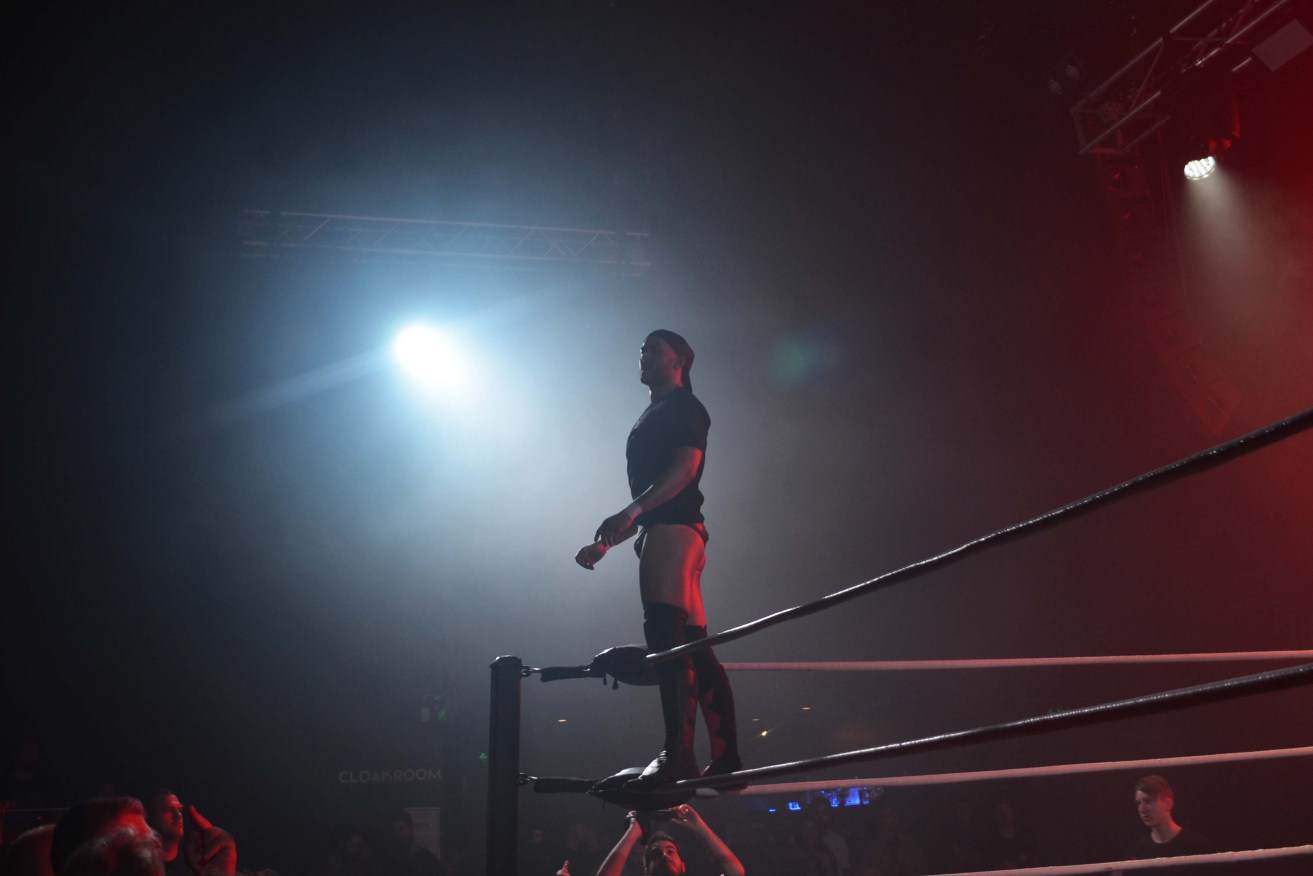

Jensen Hunt, real name Jack Styles, kissing the sky with his fist.

One night in the weights room, between a set of barbell lifts, Jack tells me his passion for wrestling started when he was a five-year-old kid, as he would watch sessions on the Channel 9 telecast with his brother. Jack made the jump from punter to participant a couple years ago, and says he keeps returning to training because wrestling is “a complete show; a real rock concert,” and that it helped him put his life into perspective.

Jack says his parents are supportive. When they saw him wrestle for the first time his dad was impressed he had the strength to heave another man. His mum on the other hand liked the get-up. “My mum loved that I wanted to become a wrestler,” says Jack, laughing. “She’s a costume maker so she made the robe for my first match.”

He also tells me he’s ambassador for Beyond Blue. “One of our guys killed himself and that rocked us a little bit, but we’re all in it together,” he says.

His left tattoo says “Even through the darkest days this fire burns always” and his right bicep reads “Better a diamond with a flaw than a pebble without.”

As a result of the death in the professional wrestling community, Jack said he signed up to Beyond Blue to be a part of their speaker’s bureau. Although he recently announced he would step away from the role to focus on his continued journey of his own, “mental and physical well-being,” I would often find Jack peddling his signed headshots at matches. He donated a portion of the profits of these sales to Beyond Blue.

“We’re all supportive of one another,” he says.

With any physically demanding sport, there is a dark side to the repeated trauma of wrestling. When American veteran wrestler Chris Benoit killed his wife and their son before killing himself, leading experts believed Benoit suffered from dementia induced by repeated, untreated concussions. Neuropathological tests showed he suffered from extensive brain damage. But his contractor, World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), said this was “speculative”.

It’s hard to know how much-repeated physical action the body can sustain before it responds, sometimes violently. However, something that RCW does well through their micro-communications and larger gestures – like Jack’s Beyond Blue advocacy – is encourage conversation, support and safety.

At the end of training weeks before, wrestler Stephen Miller punctuated this idea openness. He thanked the group of beefy men for not making him feel “soft”.

“You know, I was really worried about training tonight,” he said, looking at the ground.

“I wasn’t feeling too hot on some of the moves, and made the decision to sit out at times when I didn’t feel comfortable. But I’m glad I was supported and that nobody called me soft or anything like that… so yeah, thank you for making me feel supported.”

When Stephen said this, the other wrestlers including Jack, rallied around him saying “no worries mate”. From the inside this may not look like a big deal, but from the outside, where all you can see looking in is austere masculinity, this is a big deal.

I asked Matt Basso, co-owner of RCW, about support and what it means to him. He said the gym has helped him cope with “crappy days”, and that it personally changed his life.

Matt Basso getting real during training.

A promotional marketing meeting, a logistical space where the wrestlers plan their next move, and the epicentre of the gym.

“I honestly can’t say enough about how much this company and this sport means to me,” said Matt.

“It’s given me confidence, it’s given me direction, it’s helped me in terms of public speaking, physical strength, it’s got me a group of friends that have a similar experience to what I do. I don’t feel ridiculed,” he added.

“This is a very loving environment.” Matt mentioned support from his family and others to participate in the sport was a slow burn. Matt and his brother Chris, the other co-owner of RCW, were always into wrestling, but Matt was “nerdy” kid. He said he hid his hunger for wrestling from others as he was often ridiculed.

“Me and Chris were sometimes asked by other kids ‘why don’t you do the real stuff like UFC or martial arts’.

said Matt.

“Well, mate they’re two different things. They’re not trying to pretend that wrestling is real. I’m telling you that this is a performance sport.”

When Matt and Chris told their dad they wanted to stop playing football and train at the Monster Factory, an independent professional wrestling gym in the northern suburbs, their dad was disappointed. Matt says that although his dad eventually came around to wrestling with leaps and bounds – “he would drive us an hour often to go to training,” said Matt – others didn’t.

Despite this, Matt has been training professionally for 16 years and is the Don at his own gym. He says the future is bright for some the wrestlers at RCW as they’ve got the talen and the drive to make the big time. In terms of what Matt sees for the future of himself, he’s quietly hoping to be picked up by a larger network. But he’d be just as rapt to have the financial backing to quit his 9am to 5pm desk job and coach at the gym full-time.

I asked him about what Lachie said – about so many wrestlers getting smacked around, punched, slapped and concussed for so little – and why he keeps coming back. What is it about professional wrestling that is so intoxicating for people?

Every time I get to the gym and get into the ring, I remember what it felt like as a kid watching wrestling

“I remember that feeling of wonder, and that feeling of adrenaline.

“I love it because I grew up playing physical sports like football, and I always love going headfirst into packs, tackling each other, getting thrown around.

“I also loved doing drama, and for me it’s a great release of creativity because you’re telling stories, I’m working with developing people on their characters.

“You’re doing costume design, you’re writing scripts, you’re writing long stories that go over 10 seasons with character development and twists and turns.

“I get a big kick out of seeing people when they first come to the gym and they first step in the ring and their eyes light up.

“I can tell that at that moment they have the same feeling I did.

“If you come to a wrestling show there’s a chance that the guys are going to spill over the barrier and into your lap and as you cheer and boo that’s going to effect the story that’s actually happening in front of you.

“Wrestling is a chance to be a part of something.”

If this article has raised issues for you, you can call LifeLine on 13 11 14.