Spinning South Australia: how colonial ‘marketing’ was undermined by reality

Landholders in the new colony of South Australia spruiked its delights to entice more immigrants from England, but disillusioned labourers who’d already made the long journey sent their own letters home – telling friends and relatives not to bother, new research has discovered.

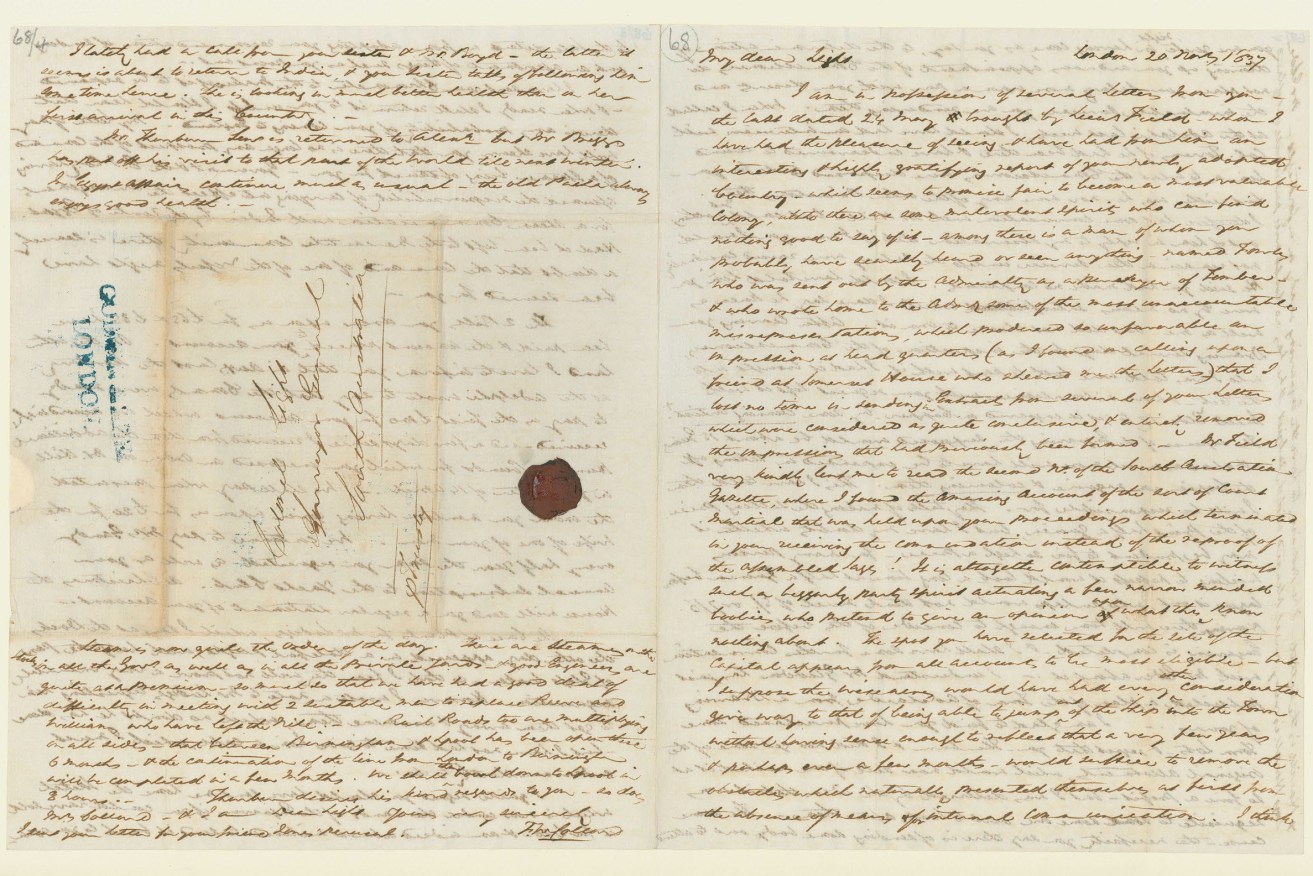

F.W Collard's letter to William Light dated 20 November 1837. Supplied by the State Library South Australia

That revealing divide – of class and optimism within a fledgling, far-flung colony – is the standout message from a study of colonial era letters spanning 1836-50, by Adelaide architectural historian Dr Jade Riddle.

Riddle spent a year trawling through archived letters at the State Library of South Australia and the University of Adelaide’s Barr Smith Library to gauge how settlers felt as Adelaide developed.

She examined communications from 1836, when British settlers first arrived and the colony proclaimed, to 1850, when South Australia was granted the right to self-govern.

“The key takeaway from my research was that the people that had a landed interest in South Australia were promoting it very positively and then other people, mostly the labourers, didn’t have that reality,” Riddle said.

“By the time we get towards the end of the 1850s, the narrative does start to get brighter (for the labourers).

“The promises of hope do catch up to the reality; suddenly the narrative starts changing.

“But in those early years, what they were saying back home in England, before they got here, didn’t match what happened when they got here.”

Port Adelaide at the beginning of colonisation. Supplied by the State Library South Australia B 15276/7

Port Adelaide at the beginning of colonisation. Supplied by the State Library South Australia B 15276/7

Riddle completed her PhD at the University of Adelaide’s School of Architecture and the Built Environment in 2018 in architectural and urban history.

She examined how emotional representations of early modern London changed the way its inhabitants understood the metropolis.

Following the completion of this research, Riddle was awarded the 2018 Bill Cowan Barr Smith Library Fellowship, which allowed her to extend this work but with a local focus.

She turned her attention to understanding how Adelaide was represented and constructed through written letters by the people that founded it.

Stakeholders – which included the British Government, the South Australian Colonisation Commission and landowners – touted South Australia as a new opportunity for labourers through official records such as publications, newspapers and circular newsletters both in South Australia and overseas.

But the sales pitch was undermined by labourers writing letters to family back home, expressing dissatisfaction with their migration, their living conditions and the overall colony of South Australia.

“There is this official representation of people who had an interest and there was this undercurrent of people who were thinking this wasn’t what they wanted,” Riddle said.

“(The land owners) had financial interests, and needed to sell or lease their land and needed people to work on it.”

Riddle said this “financial interest” is a possible explanation of why promotional accounts of the colony can be found publicly.

An example of this is a letter from colonialist stakeholder F.W Collard to the first Surveyor-General to the colony of south Australia Colonel William Light, dated 20 November 1837.

“…have had an interesting and highly gratifying report of your newly adopted country which seems to promise to become a most valuable colony. Although there are some malevolent spirits who can find nothing good to say of it – among them is a man whom you probably have scarcely heard or seen anything named Fowler… who wrote home some of the most unfavourable misrepresentation.”

Edward Wakefield, a South Australian colonial architect, targeted migration to the colony at two interest groups: landowners and workers.

“Wakefield proposed the sale of Crown Lands … in small units at ‘a sufficient price’ rather than granting large tracts of land for free, such as had happened in other colonies such as Sydney,” said Riddle.

“The proceeds of these sales would then pay for these poorer labourers to immigrate from Great Britain.”

Riddle said landowners and stakeholders that promoted immigration kept labour “overstocked” and wages low due to an abundance of workers.

But the reality of their colonial lives was being channelled home.

“People who moved to Adelaide were sending letters home to their families and their friends, telling them it was an awful place to live and to not move here,” she said.

Riddle says a letter from Mary Thomas, dated March 1840, articulates the dissatisfaction.

“For my part I would exchange it (their cottage) for a cow pen in England, even if I could have those comforts which are incompatible with this country or at least be free from the annoyances to which this climate subjects us…

“If I were now in England with the experiences I have had and recollecting the dangers and difficulties I have undergone nothing would induce me to return to South Australia.”

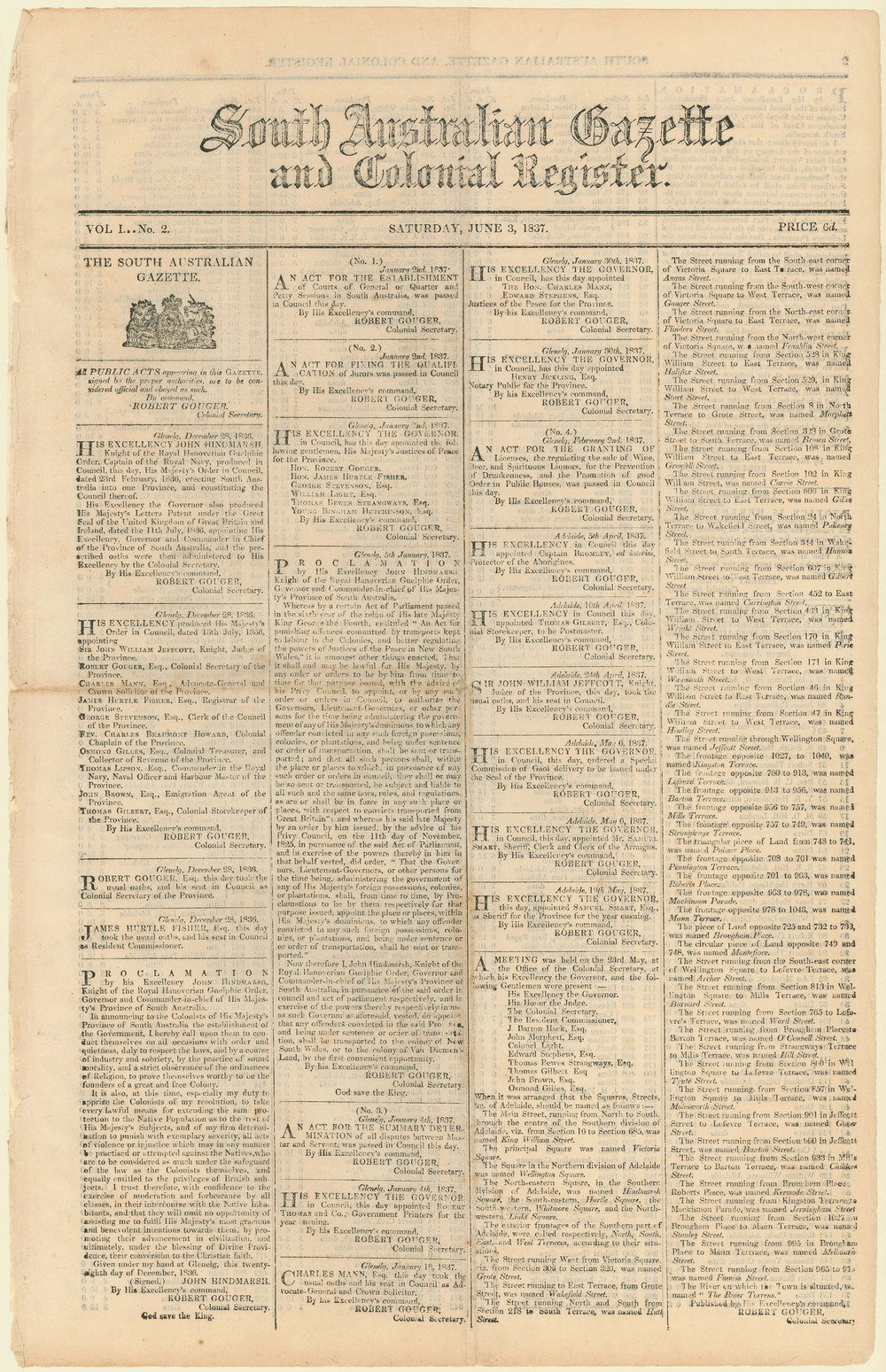

The criticism didn’t please the colony’s leaders, with Riddle finding an 1839 mention in the South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register attempting to discredit such accounts.

The Register describes the testimonies as, “false, distorted, garbled, and in some cases … manufactured statements of Ignorant emigrants.”

The Register, originally the South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register, was South Australia’s first newspaper. Dated June 3 1837. Supplied by the State Library of South Australia

But Riddle said such damning testimonies from migrants created real problems for the infant colony, including low immigration rates, which contributed to the colonial administration almost declaring bankruptcy in 1840.

“(It) was promoted as the land of promise,” said Riddle.

“Marketing the colony as a place of hope and opportunity, coupled with the apparent broken promise of land being surveyed and ready to occupy, resulted in a very different reality for the early settlers as they arrived.”

Riddle said this dissatisfaction changed in the end of 1840, as letters by labourers noted opportunities available for those willing to “work hard” within the colony.

However, after Riddle completed this study into Adelaide’s past, she said she saw similarities with how land is sub-developed and sold in contemporary South Australia.

“Just as in the early days of Adelaide, our new communities are created when somebody with wealth buys large tracts of land and subdivides it and sells it into smaller plots,” she said.

“The (housing) narrative seemed to have shifted slightly, and they’re not actually targeting the people buying the house any more, but they’re actually targeting the parents trying to get their kids out of the house, which is pretty similar to what was actually happening back when we first settled Adelaide.

“But it appears that the current early stages of creating urban communities in Adelaide is more often than not repeating history, rather than learning from it.”

All letters directly quoted in this story were supplied by and are currently held at the State Library of South Australia.