What went wrong? Seven days that changed SA

SPECIAL REPORT | With the relationship between governing authorities and the media under an intense spotlight in the past week, Tom Richardson explores the decisions and justifications of SA’s COVID cluster response and ensuing lockdown across the seven days that shocked South Australia.

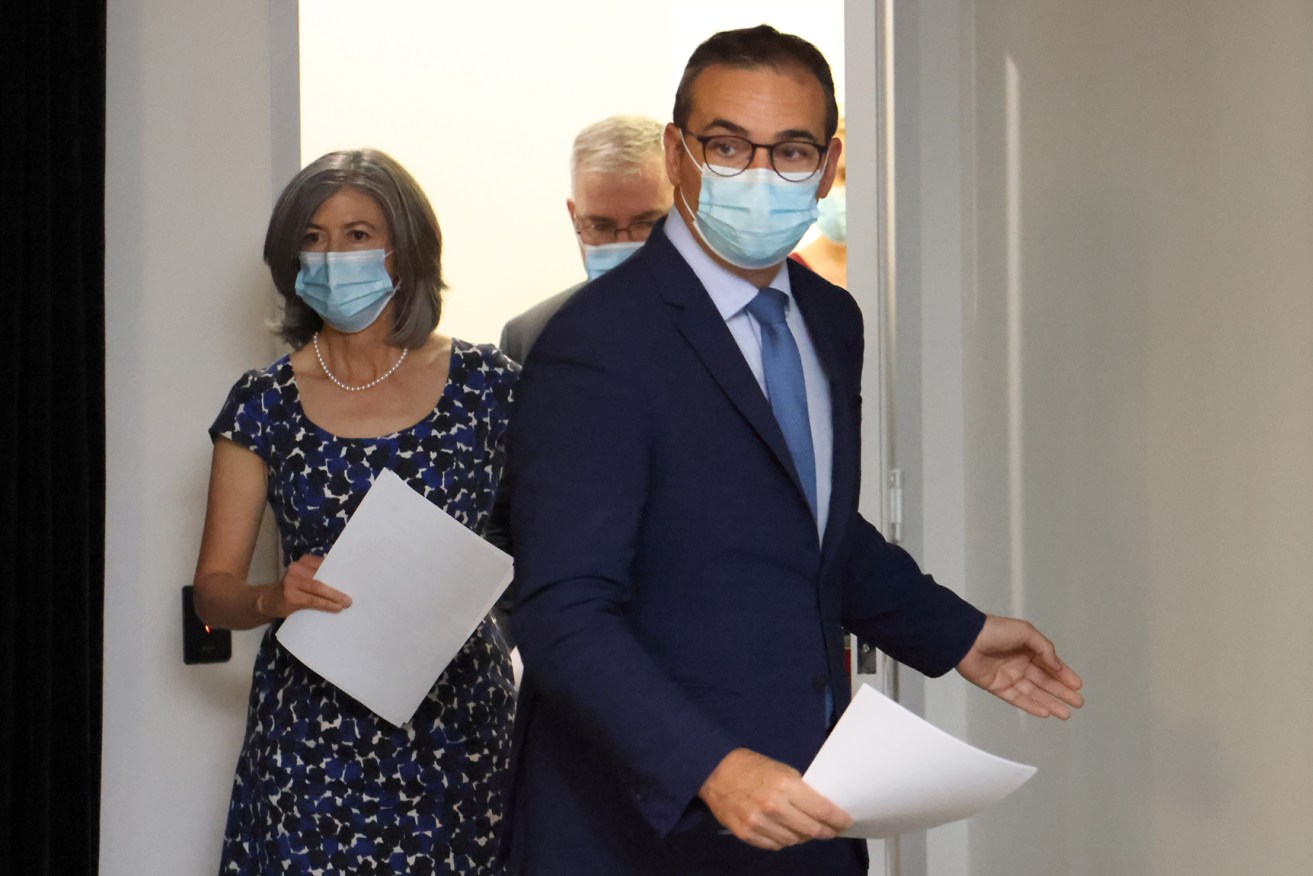

Nicola Spurrier, Stephen Wade and Steven Marshall. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

“Welcome to South Australia’s daily COVID update.

“Today, I’m joined by the Honourable Stephen Wade, the minister for Health and Wellbeing in SA; Professor Nicola Spurrier, the Chief Public Health Officer; and Commissioner Grant Stevens, who is also the State Coordinator during this major emergency declaration.”

Many South Australians would likely know by rote the above spiel, which Premier Steven Marshall utters at the outset of each of his daily coronavirus briefings, every time.

Throughout last week, the monologue has preceded a series of increasingly grim revelations, as thousands – on some days, hundreds of thousands – of South Australians watch on in horrified thrall.

Friday, November 20

It was one of the more remarkable admissions in state political history: a six-day, near-complete lockdown of South Australia – some 1.7 million people – would be called off early, because a man who worked part-time in a pizzeria had told “a lie”.

The man, later revealed to be a 36-year-old Spanish national in SA on a legitimate but soon-to-expire graduate visa, had been the case that became the catalyst for the great ‘pause’ – a shutdown with a $100 million impact on the state economy.’

“That was the absolute correct decision based upon the information which was available at the time,” Marshall insisted, stony-faced.

SA Health contact tracers had linked the Spaniard, who worked in the kitchen of the Stamford medi-hotel, to the Woodville Pizza Bar, but believed him to be a customer rather than an employee.

But further police inquiries revealed, as Commissioner Grant Stevens explained, he was instead “working there and had been working there for several shifts”.

Marshall’s rhetoric was incandescent.

The man, he said, “deliberately misled our contact tracing team – their story didn’t add up”.

“We pursued them – and we now know that they lied,” he said.

“To say that that I am fuming about the actions of this individual is an absolute understatement – the selfish actions of this individual have put our whole state in a very difficult situation… his actions have affected businesses, individuals, family groups and is completely and utterly unacceptable.

“I will not let the disgraceful conduct of a single individual keep SA in these circuit-breaker conditions one day longer than is necessary.”

But Stevens was unequivocal: without the lie – the story that didn’t add up – the lockdown would never have happened.

“That clearly changes the circumstances, and had this person been truthful to the contact tracing teams, we would not have gone into a six-day lockdown,” he said.

“We were operating on a premise that this person had simply gone to a pizza shop – a very short exposure – and walked away having contracted the virus… we now know that they are a very close contact of another person who is confirmed as being positive with COVID – it’s changed the dynamics substantially.”

By day’s end a 20-person police taskforce had been established to examine broader legal questions about the man and his associates.

But throughout a week of questioning, no such scrutiny appeared to have gone into addressing when and how the virus escaped the Peppers medi-hotel to begin with.

Sunday, November 15

On the morning of Sunday, November 15, SA Health media unit staff did a ring-around of reporters to alert them that an important media conference would be held that afternoon, at 3.15pm – the timeslot synonymous with coronavirus-related news.

And the news on this occasion was indeed “very troubling”, as Professor Nicola Spurrier put it that day in her reassuring medico-meets-schoolteacher manner.

“We have some new cases to discuss,” she said, with some understatement.

The first, which she dispensed with quickly, was relatively trivial: a 30-year-old man returned from overseas who had tested positive to the virus still running rampant worldwide.

“He’s in quarantine in a medi-hotel, and there’s no concerns at all with him or that process,” Spurrier noted.

But there was more.

She said an 80-year-old woman, who had presented at the Lyell McEwin Hospital in the “early hours of Saturday morning” with unrelated symptoms, had emitted a couple of coughs – enough to pique the curiosity of junior duty doctor Dharminy Thurairatnam, who ordered a COVID test.

The results came back the following morning, confirming SA’s first case of community transmission since April.

That was enough to send SA Health’s response team into overdrive, isolating close contacts and embarking on a testing blitz – which yielded two more positive cases, just minutes before Spurrier’s Sunday media conference.

They were a woman in her 50s and her husband, in his 60s – the daughter and son-in-law of the octogenarian patient.

While her mother was the first positive case in the growing cluster, it was her daughter who proved to be ‘patient zero’.

For she worked in ‘back of house’ as a cleaner at Waymouth St’s Peppers Hotel – one of the facilities redesignated as a ‘medi-hotel’ for quarantining returned overseas travellers.*

“Obviously,” Spurrier noted, “this is where we’re considering the source to be.”

Spurrier was worried. The elderly woman was the matriarch of a large family, reported by some outlets as of Indian descent, several of whom were already displaying COVID symptoms.

While she had worn a mask in the hospital – which saw dozens of patients and staff, including several from the mental health unit, isolated and tested – she had also visited other locations while infectious, including a Parafield Plaza supermarket.

The cases became known as the Parafield Cluster.

Professor Nicola Spurrier. Photo: David Mariuz/AAP

South Australians would later be told they had become complacent, even though it was not the actions of any in the community that saw the virus re-emerge.

But in truth, many had become complacent, smugly revelling in Marshall’s repeated assertions that the state was possibly the safest place in the world.

There is no public health risk

Since Adelaide boosted its city medi-hotel capacity in September, there had been a regular but slow stream of new cases in SA. There were 34 in October, with a highest single-day caseload of four. Approaching halfway through November, there were already 22 cases for the month, peaking with five on a single day.

But none of it was remarkable – generally not even enough to warrant a media conference.

Instead, SA Health would put out its daily afternoon media update – always around 3.15pm – noting that each new case was a returned traveller who had been in a medi-hotel since arrival.

“There is no public health risk,” the pro forma release always said.

Indeed, as Spurrier herself said of the new case on Sunday, November 15 that wasn’t part of the cluster: “He’s in quarantine in a medi-hotel, and there’s no concerns at all with him or that process.”

Except that now, there were.

The Chief Public Health Officer noted she had already implemented a significant change.

“We have, for some time, had voluntary testing in our medi-hotels for staff, but from today we’re implementing a mandatory seven-day test requirement for all staff across all our medi-hotels,” she said.

“That’s likely to be a first for Australia, but I really believe this is the way we should be going.”

Many observers expressed surprise that staff were not already tested regularly.

Instead, they had merely signed a declaration that they are well, and sought a voluntary test if they developed symptoms.

Spurrier also noted that she was awaiting genomic testing to locate the original source of the infection – which medi-hotel resident had somehow infected the cleaner.

“This is a highly infectious disease,” she said.

“We know it can be spread very easily with droplets when people get close to each other, but I think we’re finding more and more that it can be transmitted through fomites.”

Fomites are defined as objects or materials – surfaces such as clothes, utensils, and furniture – that are likely to pass infection, for example, as Spurrier explained, “when people touch their nose or touch their face, and then touch other objects”.

“Even when we have perfect PPE [Personal Protective Equipment], we still have seen virus transmission – which is exactly why I’m introducing mandatory testing from today,” she said.

“I think this is really where we just need to keep improving our systems.”

She pointed out that “we had a review we were part of – the national review undertaken by the Commonwealth – and we were seen to have very good systems in place”.

The review in question was the National Review of Hotel Quarantine, published last month and authored by former senior bureaucrat – including Commonwealth Health Department boss – Jane Halton.

It would be mentioned many times in the coming week, as the Government reminded reporters that it had “passed with flying colours”, and even been given a “gold star”.

The Peppers hotel in Waymouth Street – one of Adelaide’s “medi-hotels”. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

But Spurrier’s apprehensive tone was to prove well-founded.

Later on Sunday, some media were told of a fourth positive test, another family member who worked at Yatala Labour Prison.

By the following morning, Spurrier and Marshall hit the breakfast radio airwaves to reveal the cluster had grown overnight to 17 confirmed cases.

Within two more days, the entire state would be sent into a brief but almost-total lockdown.

And the primary avenue through which all this information was imparted was the daily media briefing.

The most broken organisation I have ever witnessed

One of the many ironies of the year 2020 is the esteem in which the brand SA Health has come to be held.

The minister who oversees it, Stephen Wade, spent many years in Opposition doggedly trashing it on a near-daily basis, and the reputation was hardly enhanced when the head of the KordaMentha razor gang he appointed to run the ruler over the agency later described the Central Adelaide Local Health Network as “the most broken organisation I have ever witnessed, both financially and culturally… in my 40 years of experience”.

Former Independent Commissioner Against Corruption Bruce Lander detailed an agency riddled with maladministration and ripe for corruption, saying as recently as August the problems he had detailed had “not been addressed… were allowed to fester [and] they’re getting worse”.

The SA Health media unit has never been a favourite of television news reporters in particular, largely because of a longstanding and seemingly cultural predisposition to schedule important media conferences in the mid-to-late afternoon – around 3.15pm, in fact.

This was generally taken as a mechanism to avoid too much scrutiny – deadline pressure would ensure media conferences on bombshell breaking news announcements held at that time were less likely to drag on.

It’s unclear whether the mid-afternoon timeslot for the daily COVID briefings when they began in earnest in March were a nod to this tradition, but it was noted at the time that it was at odds with other Australian jurisdictions, which all announced their case numbers in the early-to-mid-morning.

SA Health countered that their own reporting deadline was mid-afternoon, so it made sense to hold the media conference then.

Some weeks later, they quietly switched their internal reporting deadline to mid-morning, without mentioning it publicly.

This meant by the time the media conferences were beamed live via Facebook to thousands of eager viewers, the figures were already, potentially, out of date.

But as SA’s coronavirus threat diminished, the daily 3.15pm briefings adopted an increasing sense of theatre: you could almost hear the drumroll as Marshall uttered his regular opening refrain – “Welcome to South Australia’s daily COVID update” – before throwing the spotlight to Spurrier to read out the day’s numbers.

The daily COVID update is considered definitive, but sometimes lacks detail. Photo: AAP/Kelly Barnes

The odd thing about the daily briefing was that it was regularly light on detail or nuance, particularly when detailing changing restrictions – but was nonetheless considered definitive.

InDaily has spoken to business owners who never received further correspondence detailing their obligations or the specific restrictions impacting them – initially at least, they just had to tune in and get the gist.

Adding to the theatre was the online audience, which would banter among themselves as they awaited the state’s COVID leadership foursome – Marshall, Spurrier, Stevens and Wade – the latter of whom had the luckiest gig of all, rarely being asked a single question.

The Facebookers would post in the comments, trying to guess what colour tie Marshall would wear, and placing bets on what the daily caseload figure would be.

And then the media conference would start, and the comments feed would quickly become a diatribe against the assembled media.

A particular bugbear of some of the commenters was when the questioning turned to the then-abandoned AFL season, whose cause Marshall’s government didn’t appear to be doing any favours.

Some singled out Channel 7’s Mike Smithson for, as they saw it, hogging the press conferences – not realising that the media pack had adopted a pool arrangement to allow appropriate social distancing, with Smithson asking questions on behalf of several other reporters.

While most networks streamed their own feed of the briefing on any given day, it was – perhaps unsurprisingly – the commenters on the Premier’s own Facebook page that displayed the most vitriol towards the media pack.

Among all the strange things that happened in SA last week, the least remarked upon was nonetheless, for longtime journalists, significant: the daily health briefing ‘pivoted’ from afternoon to morning.

As the Parafield Cluster expanded, the numbers were moving so quickly that delaying their announcement for the 3.15pm showcase would make them potentially redundant.

Monday, November 16

By the afternoon of Monday, November 16 – the second day of the crisis – Marshall told South Australians they were facing “our biggest test to date”.

Testing sites were facing major delays, as queues snaked hundreds of metres down major roads.

The Premier announced a range of suppression measures: all inbound international flights would be suspended for the remainder of the week, people were advised to work from home where possible and avoid unnecessary travel.

In strict new directions, gyms, recreation centres and play cafes would close for two weeks, with community sports and training cancelled.

Funeral attendances would be capped at 50, church services at 100 and no more than 10 people could meet together at a family home.

“We don’t want to keep these restrictions in place for one day longer than we need to,” Marshall assured viewers – a mantra he’d adopted back in the ‘first wave’ days.

The good news – for now – was that the cluster had not increased beyond that morning’s radio announcement: it remained at 17 active cases.

However, the daily numbers were ambiguous.

Because of the evolving emergency, health authorities had been updating some cases outside of the normal reporting times, confusing SA Health’s adopted procedure.

Spurrier initially noted that “putting the cases together with yesterday, there are 18 new cases in total”, before then explaining that “13 of these cases are linked to the Parafield Cluster and we reported four of those yesterday”.

A further five new cases involved returned travellers in hotel quarantine.

As always, there was no risk to public safety.

Nicola Spurrier explaining the numbers. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Later in the media conference, assembled reporters sought to clarify the numbers – much to the chagrin of the online commenters.

“Do journos not listen?” one opined.

“Why do they keep asking the same questions? Maths clearly not a strong point.”

Spurrier, however, empathised that “the numbers may be difficult to add up and I actually find it difficult as well when I’m looking at a whole range of different numbers”.

“But we report case numbers for the previous 24 hours [and] I can confirm we haven’t had any new cases to add to that cluster – and I am feeling very positive about that, I can tell you!” she said.

“We reported some yesterday, and I updated earlier on radio [but] since the 17 there’s not been anything new.

“Today we’ve got 18 new cases in total, but there’s 17 in the cluster – and then there’s five that had their infection acquired overseas,” she said, before adding that there were also a further “three children who have tested negative but we’re treating as cases”.

Amid further questioning, she declared: “We will give you the numbers, but I can give you absolutely definitively – there’s 17 cases in this cluster.”

In fact, there were 16.

And, despite repeated requests, SA Health did not clarify the number with most media.

One outlet was told, wrongly, that one of the children had since tested positive and was thus counted in the daily total.

By evening, the only media outlet reporting the cluster’s total as 16 – plus three children expected to test positive – was News Corp’s The Advertiser.

When InDaily sought to clarify the discrepancy with SA Health, it was told to wait until the following day’s briefing.

It’s difficult to really respond to that

Through it all, questions were beginning to be asked about whether processes at the Peppers medi-hotel had broken down.

Spurrier was asked if authorities had identified any lapses in infection control, replying: “Look, you know, we’re reviewing and monitoring on a daily and hourly basis – and that’s the reason for having nurses and infection control practitioners in the medi-hotels… so it’s difficult to really respond to that.”

A huge queue at the Victoria Park COVID testing station last week. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

As SA Health released more and more information on potential public hotspots – urging people who may have visited them to isolate and get tested – more questions were asked about medi-hotel staff working more than one job.

One of the security guards who caught the disease also worked at a Woodville Road pizzeria, the Woodville Pizza Bar.

On Monday last week, Spurrier noted that “a number of the hotels work as a conglomerate [and] they do have staff going between sites”.

She argued that generally “the real way of preventing the transmission of the disease is by using PPE” which “can successfully stop [the] transfer of droplets”.

However, she noted again, “what I think we are seeing, possibly because we’re in a community where we haven’t had much disease, there’s possibly more of a role for fomite transmission.”

At this stage though, both Government and public were more concerned with the future than the past.

“What we’re facing is indeed a second wave,” said Spurrier, noting “an element of complacency has inevitably occurred here in SA”.

Quizzed on the medi-hotel system, Marshall said on Monday: “I think the people of SA just want a speedy resolution to this cluster – there’s plenty of time to review this afterwards.”

“We’re not apportioning blame at the moment, what we’re doing is acting very, very swiftly to get on top of this cluster,” he said.

Spurrier said she had now raised the question of mandatorily testing medi-hotel workers with the national peak public health emergency panel on which she sits, the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee.

“There’s nowhere else in Australia in the medi-hotel system where mandatory testing is being done,” she insisted.

“But the issue here is that at least one of the people, if not two, have not had any symptoms at all [so] if we rely on people coming forward just when they have symptoms we may miss something.”

There was no commitment to an extraordinary review, with Spurrier noting “we do a regular audit of our hotel quarantine system”, which “we treat like a hospital”.

Police Commissioner Grant Stevens was adamant: “I couldn’t be more confident that we’re providing as secure an arrangement as possible in relation to our medi-hotels.”

“I can absolutely assure the SA community that the hotel quarantine system in SA is as good as anywhere in Australia,” he said.

“We’ve been independently reviewed and we passed with flying colours… I’m quite certain there’s no complacency within the hotel quarantine environment [but] this is a wake-up call for us that COVID-19 has not gone away.”

Tuesday, November 17

Five new cases – with four linked to the Parafield Cluster – saw more schools close as three members of one of the Peppers security guard’s family fell ill.

Significantly, Spurrier had received her all-important genomic information – tracing the cluster to a medi-hotel guest who arrived from the UK on November 2, and was tested the following day.

Spurrier noted some peculiar aspects of the virus strain.

“I feel somewhat surprised that we’ve got so many people infected, but with such little symptoms,” she said.

“It may also be because they’re in the early stages of the disease and may get more symptoms as time progresses…

“It’s a very, very tricky disease, this novel coronavirus – it’s very sneaky.”

But a remarkable twist was about to sneak up on South Australia.

Wednesday, November 18

The first indication that things were about to change dramatically came when the Government media adviser appointed to usher journalists through the security coded entrance to the State Administration Building media room arrived wearing a disposable face mask.

So too, for the first time, did Spurrier, Stevens and Marshall, who declared: “We are going hard and we are going early… we cannot wait to see how bad this becomes.”

The health advice, he declared, is “that we need a circuit-breaker”.

“We need breathing space for a contact-tracing blitz… we need our community to pause for six days.”

This ‘pause’ – the protagonists eschewed the term ‘lockdown’, at least initially – involved wide-ranging restrictions, including a whole-of-state stay-at-home order, bans on planned weddings and funerals, school and university closures and the temporary cessation of trading.

Stevens suggested he had needed convincing about the move.

“I’ve challenged the control agency, SA Health, on the need for these significant impositions that we’re about to place on the community… and I’m 100 per cent supportive of the approach that’s being taken.”

The authorities preached mixed messages on the use of masks, which Stevens initially declared “will be required for all areas outside the home”.

He later clarified that masks were not currently mandated, but were strongly encouraged.

On radio the following day, Marshall contradicted this, insisting masks must be worn – a measure Stevens would continue to insist would not be enforced.

Spurrier then gave the daily case numbers, which remarkably showed just two new cases – but one was particularly relevant.

“I want to talk you through the rationale of why we’re asking all South Australians to do this,” she said.

“This particular strain has had certain characteristics – it has a very, very short incubation period [and] that means when somebody gets exposed, it’s taking 24 hours or even less for that person to become infectious to others… and the other characteristic we’ve seen of cases so far is they’ve had minimal symptoms – and sometimes no symptoms – but have been able to pass it on to other people.”

She then explained that she had received information the previous evening that “cements my concerns”, about “a young man who works at one of our medi-hotels”.

“But it was not the Peppers medi-hotel, where our other three cases have been – it was at the Stamford. And in fact this person wasn’t a security guard, wasn’t a nurse and wasn’t a police officer – but worked in the kitchen… and that made us very concerned, because we couldn’t work out how on earth that person had become infected – how were those two medi-hotels linked?”

Last night, Spurrier declared, “we made the link”.

The link was the Woodville Road pizzeria, the Woodville Pizza Bar.

“One of the [infected] security guards in the [Peppers] medi-hotel, like many people, had more than one job – and worked part time at that pizza bar,” said Spurrier.

“And the case we got last night also worked in the pizza bar at the same time as the person who was at the Stamford went and got a pizza – so we absolutely have linked all of that.

“We’ll get the genomics to prove it, but we are absolutely certain with our history-taking that that’s what’s happened.”

According to Spurrier on Wednesday, it was this revelation that “cemented my fears that this virus is breeding very, very rapidly”.

“You’ve got a short incubation period… I know this is an absolutely big ask, but if we leave this any longer then we’re going to be in this for the long haul – and we’ll be like the experience in Victoria where we have to go into significant lockdown for a very long period of time to snuff it out,” she said.

“We don’t have any time to wait – if I just thought about this all day and then told the Police Commissioner and the Premier tonight, we’d already be that 12 hours behind – so we really do need to act fast on this.”

Gee, they’re doing things a bit strange there in SA

It was, she acknowledged, “a different strategy”.

“And I guess there’ll be other public health physicians and epidemiologists and other specialists around Australia who’ll be looking at us and saying ‘Gee, they’re doing things a bit strange there in SA!’ but I am using the science and I’m also using the information that my team already has got from our experience here.”

Thursday, November 19

“We have woken up to a very different SA today,” Marshall told the assembled reporters and Facebook viewers.

Then, in a mixed metaphor that perpetuated his ongoing propensity to somehow characterise – and demonise – the disease, he noted that “indecision plays into the hands of this virus”, which would be “very difficult to eradicate once it gets a foothold in the community”.

A deserted Rundle Mall just after 8.30am last Thursday. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

For the second time that week, the daily briefing proved an unreliable source of accurate information: there were no new cases on Thursday, but the total number in the cluster was revealed to be 23 – higher than the previous day.

“And I am sorry, I apologise – I said 22 yesterday, but it is definitely 23 cases linked to this cluster,” Spurrier reported.

Ironically, it was later revised back down to 22 after one patient was declared to have returned a false positive.

“You might be saying, ‘why have we got no new cases and I’m not able to get out of the house?” Spurrier pondered on day one of the “circuit breaker”.

But she was adamant that “we still have potentially thousands of South Australians who visited a site of concern and may be carrying this disease”, including “anybody who has been in or out or had a pizza delivery or a Menulog delivery”.

“This is the reason for our pause,” she declared.

By week’s end, she would be insisting the decision was a far more holistic one, after it was revealed the key piece of the puzzle – the Stamford worker – had deliberately concealed the extent of his involvement.

But regardless of the “lie” he told – or any other legal issues he might face – the fact remains he would not have contracted the virus were it not that a security guard working at the Peppers Hotel also worked part-time in the pizzeria.

But authorities took umbrage at questions over whether the state should mandate that such workers in medi-hotels should not work two jobs – and compensate them so there is no requirement for them to do so.

Asked on Thursday whether the security guard “should have been allowed to have a second job”, Marshall again noted that “we subjected ourselves in SA to that independent audit… done by Jane Halton [and] I don’t believe there was a recommendation with regards to people working at multiple sites, but I’m happy to check that”.

“What we know is we got a very good report card from that audit – but we’re always looking to improve the way we do manage those sites, and I know that Health is already looking at that,” he said.

“The reality is this is a highly contagious disease – there’s always risks when you bring Australians in for quarantine in a supervised hotel [but] we have no evidence to suggest that anything that has happened in our hotel quarantine hasn’t met the standard.”

He added, however: “Whether that standard – which is a nationally-accepted standard – is right, we need to look into.”

The evidence throughout the Inquiry was replete with examples of problems associated with workers being engaged on a casual and itinerant basis

It’s true that the Halton review did not specifically address people working across multiple sites.

But the interim report of Justice Jennifer Coate into Victoria’s quarantine debacle does.

That report, published this month, specifically cited “personnel working at multiple sites” among a range of concerns and noting: “Where possible, personnel working within a facility-based model should not work across multiple quarantine sites, nor should they work in any other environment.”

“Having dedicated, salaried personnel, will help to minimise the risk of transmission between quarantine sites and onwards into the community,” the report said.

“The evidence throughout the Inquiry was replete with examples of problems associated with workers being engaged on a casual and itinerant basis.”

The report specifically recommended employing “dedicated personnel”, saying “every effort must be made to ensure that all personnel working at the facility are not working across multiple quarantine sites and not working in other forms of employment.”

Asked whether SA authorities looked at the Victorian lessons, Marshall insisted: “We have constantly looked at what’s happened in other states of Australia but also other jurisdictions around the world.”

Asked again whether that specifically included the Victorian inquiry, he deferred to Wade, who noted: “My advice is both the chief of the [Health] Department and the Police Commissioner had specific scrutiny of the processes following the Victorian experience [and] we’ve certainly got people within Health whose sole focus is on quality assurance in relation to hotel quarantine.”

That same day, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews was announcing measures to implement the Coate recommendation, telling reporters: “Everybody who works in this program will either work for the Victorian Government or be exclusively contracted for this purpose and this purpose only.”

Grant Stevens, however, was far from convinced.

Asked to approach the podium, he launched into an extraordinary statement.

“Before you ask your question, let me give you my perspective on this perception you’re creating around our quarantine hotels,” he told reporters.

“Your expectation is that people that work in a quarantine hotel will be isolated in a complete bubble from the rest of the community while they’re providing that service…

“That’s not just security guards – that’s police officers, it’s nurses, it’s caterers, it’s cleaners, it’s hotel staff, it’s the Australian Defence Force.

“Your expectation is unreasonable. These people are part of our community and we require them to do a really important job at the moment [and] people have an entitlement to get on with their life when they’re not at work… so please balance your expectations in relation to what we’re asking these people to do, and the fact that they have lives outside of their nine-to-five job.”

The reporter to whom he appeared to direct his critique, The Advertiser’s Andrew Hough – who, in fact, had not asked about personnel working across multiple sites during the preceding media conference – responded that there was “community angst” about the issue.

“I understand the community concern,” Stevens said.

“But I would respectfully suggest the questions you ask and the way you report this creates a level of perception in the community.

“Give these people a break.”

Police Commissioner Grant Stevens: “You’re being completely unreasonable.” Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Hough then asked whether anything his newspaper had reported on the subject was inaccurate, to which Stevens conceded: “No – I accept those concerns [but] we have made an undertaking.”

“The first level of risk mitigation is to not allow people to return to Australia [but] we’ve accepted that that’s occurring and we have to manage that as best we can, and that’s what we’re doing… the next level of mitigation is to make sure we have a system in place that effectively manages those people who are returning to SA or to Australia.

“We do that as well as we can – but this is an insidious virus, which is highly contagious… let’s be balanced in our perceptions about what these people are confronting and be grateful for the fact they’re stepping up to do this job.”

Hough pressed on, insisting it was “reasonable to question” whether people working at a viral epicentre should also be allowed to work in a pizza shop.

Stevens was having none of it.

“Does it make any difference if someone who works in a medi-hotel has a second job, or goes to a gym, or sits in a cinema, participates in sport, fills their car with fuel at a petrol bowser, goes to a supermarket… these people have lives that they have to manage.

“Your expectation at the moment – the expectation you’re contributing to – is that these people go to work and then they isolate until they return to work… that is simply not possible.

“You’re being completely unreasonable – these people have lives.

“If we ask these people, including police and nurses, to go into quarantine when they’re not at work, we will not have people doing this job.

“Let’s be reasonable about this.”

It was a moment of high tension in a fraught week – a moment aimed at the reporters in the front seats but pitched to the Facebook viewers in the stands.

In essence, Stevens was responding to a question that nobody had asked, and a claim that nobody had made.

Police and nurses in medi-hotels, for instance, are already paid a living wage under an enterprise agreement, and would be unlikely to be taking a second job in a pizza bar.

Stevens was arguably taking a reasonable proposition – that the state consider supplementing wages of low-paid and casual workers in medi-hotels for the duration of the crisis – and spinning it into an attack on those workers’ right to a social life.

Remarkably though, given his diatribe, when subsequently asked whether the SA Government was reviewing the hotel quarantine program and considering “invoking a ban on working second jobs”, he did not rule it out.

“We are reviewing the program – we are constantly reviewing the program,” he said.

“There is no decision at this point in terms of banning people from certain activities outside of work [but] we’ll see what the reviews and the outcomes of those inquiries tell us.”

Asked if that concession “directly contradicted what you have fairly robustly defended today”, Stevens replied: “No, I would suggest to you that it comes down to best endeavours.”

“We need people to do this job for us, they have lives beyond their responsibilities at a medi-hotel – and we need to find that balance.”

While Stevens was strong in denouncing questions about the working arrangements of hotel staff, those working arrangements had by now become crucial to the chain of the cluster’s spread – and by the following day would be revealed to have played a key role in the decision to shut down the state.

In the context of the week, Stevens’ outburst was significant for another reason: it amplified the chorus of online bile directed against the media covering the daily briefings.

Much of which was thereafter focussed on the reporter to whom his sermon was directed.

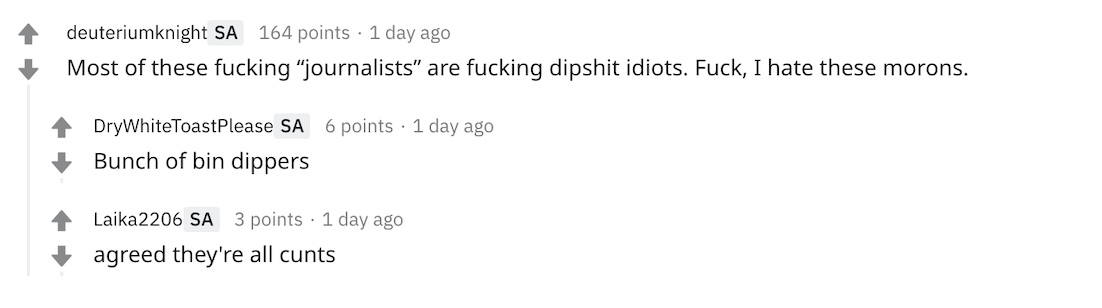

A selection of comments on a Reddit post this week.

The irony of the online audience turning against The Advertiser for its line of questioning is that there is no media outlet with which SA Health and the Marshall Government is more cosy.

While during the Victorian second wave the ‘Tiser’s stablemate, the Herald Sun, was demonised by Andrews cheerleaders for its relentlessly negative coverage, its Adelaide equivalent has taken a very different editorial line – one on occasions bordering on obsequious.

The state’s preeminent exponent of ‘access journalism’, it’s likely no other media outlet can claim as much credit for bolstering the public image of Spurrier as the state’s Chief Public Health Officer, having run multiple hagiographical features on SA’s ‘COVID Queen’.

The Advertiser has also been a beneficiary of regular drops from the Government since it came to power – a relationship that has extended into the pandemic, with its reporters frequently gifted briefings on public health matters.

Given the propensity for erroneous data to find its way into the daily briefing – with Spurrier delivering an incorrect daily total twice in the past week – the dissemination of the state’s public health information can be akin to ‘Chinese Whispers’.

For example, in her initial media outing on Sunday, November 15, Spurrier identified the elderly woman who presented to the Lyell McEwin as 80 years old – but some media outlets have since started referring to her as 81.

The Advertiser’s editor, Matt Deighton, downplayed the paper’s access, saying “all I say to the guys is ‘try and get me fresh stuff for the paper’”.

“I just ask the guys to make phone calls at 4 or 5 o’clock so the stuff I’m putting in the paper the next day isn’t the same thing that’s online in the afternoon – sometimes that works, sometimes it doesn’t,” he said.

He insisted he couldn’t care less about the politics.

“When this whole thing started, I said to my reporters: ‘we just need to keep people safe and calm’,” he said.

“That’s been the driving force through this whole thing… it doesn’t come down to the politics, my only guiding force is how do we get this community through what’s a once-in-a-lifetime crisis.

“Not to support or bag the Government or Opposition, but really try to keep people safe and calm and sane – in what’s an insane predicament.”

He insists there’s “certainly no sweetheart deal between us and the Government and us and SA Health”.

Indeed, he said some Advertiser columnists, such as former ABC radio host Matthew Abraham, had come in for criticism from readers in recent days.

“But I reckon that’s good, if people are having that discussion from opposing points of view,” he said.

“I’m not particularly bothered about the criticism the guys are copping – Huffy is doing his job and he needs to do it.

“I don’t think there’s a ‘groupthink’ in our newspaper at all.”

He said the Victorian situation was not comparable, given the much-publicised medi-hotel breaches and extended lockdown, but noted the blowback from the daily briefing was in part because “a lot of people are seeing media conferences for the first time, and seeing how it works”.

“Sometimes it’s ugly, but it’s really important,” he said.

“That’s kind of democracy at work – we get our people there and ask the hard questions… if you’re all just sitting there complying, it’s not the kind of world I want to live in.”

For the Government’s messaging, things came full circle on Saturday, the first media conference since the revelation that a lie from a pizza bar employee had sent the state into lockdown – when Spurrier’s opening gambit conspicuously cast back to that first case found in the Parafield Cluster.

“The real reason we picked that up was not because somebody had classic COVID symptoms and came to the emergency department – it was because of our astute young junior doctor, who heard a bit of a cough and thought they’d take the swab,” she declared.

With the state still reeling from the revelation that the lockdown had been – as the Government couched it – sparked by a lie, it was understandable that health authorities would seek to remind the public of its great successes.

The Murdoch-owned national broadsheet The Australian had that morning carried an opening paragraph reminiscent of its recent dealings with Victoria’s Andrews Labor Government: “Steven Marshall has been forced into a humiliating reversal of his total lockdown of two million South Australians after it emerged the government’s contact tracers had been duped by a part-time pizza worker.”

The Government needed a good news headline – and the “heroic” Dr Dharminy Thurairatnam, who is still in medi-quarantine herself, was the perfect fit.

While Spurrier celebrated her actions during Saturday’s media briefing, an exclusive interview with Thurairatnam had already been conducted with News Corp, coordinated by the SA Health media unit, to run on the front of the following day’s Sunday Mail.

A family photo of Dr Dharminy Thurairatnam, posted on facebook by SA Health.

In reality, though, Thurairatnam’s tale is as much a cautionary one as a symbol of systemic success.

By Spurrier’s own account, the doctor’s decision to test the elderly matriarch was a case of undue diligence.

“She knew what she had to do, and she heard this person cough a couple of times and thought ‘they’re not getting away without a swab’,” Spurrier said on Saturday.

“If we hadn’t had that done, we would have found out about this in about two or three weeks – and we would have had widespread community transmission by now.”

This concession yet again highlights the need to safeguard SA’s medi-hotel regime – but to date, authorities have insisted identifying what went wrong at the Peppers Hotel facility is a second order issue.

Spurrier said on Saturday her “clear understanding” is that the medi-hotel cleaner believed to be the first non-traveller infected “had nothing to do with the traveller at the hotel” who imported the COVID strain linked to the Parafield Cluster from the UK.

“But what I haven’t been able to do is just go through all the CCTV footage and suchlike,” she said.

“Of course, we are doing that investigation – but what my concern is, is getting everybody that’s positive into quarantine so they’re not spreading the disease.”

Asked about a potential “quarantine breach” at Peppers, she responded: “I’m not absolutely sure what you’re getting at with the question.”

“All I can say is we’ve had less than a week to get detailed interviews from huge numbers of people [so] we wouldn’t have had the opportunity to go through, minute-by-minute, how someone may have got the infection,” she went on.

“But what we do know is that it was a cleaner who was at back of house and that appears to have been the first case in this whole cycle.”

It was, she insisted “definitely” still under investigation, “but it hasn’t been my focus to be looking at all those details because what we really are doing is getting at the front of this wave”.

“Obviously we want to go back in a really academic way and find out how this person became infected, because that’s the way we’ll improve our medi-hotels, not just for SA but the whole of Australia.”

Asked to clarify how the virus breached the medi-hotel, Spurrier said it a “bit early for that one”, but “when we find out, let me tell you, we will be aiming to publish that so it’s widely known”.

As to the broader medi-hotel regime, “we’ve already put in place improvements”.

“We’ve already explained that we had a national review and SA got a big gold star, and we were given a few small suggestions – but nothing major in terms of improvements.”

The Halton review – and its lavish praise for SA’s medi-hotel regime – has been a default retort for the Government in the past week.

On Tuesday, Marshall told parliament that “we subjected ourselves to the independent audit [and] we came through with flying colours”.

“There were no red flags whatsoever – in fact, we were held up as an exemplar for what best practice looked like in terms of the hotel quarantine arrangements,” he said.

In fact, South Australia is only mentioned directly in the Halton review in pro forma sections summarising each state and territory’s particular arrangements and legal framework, which concludes: “To support the planning and development of quarantine arrangements, an Effective Quarantine Workstream has been established within SA Health as part of SA Health’s COVID-19 response structure to provide advice on systems and controls for the provision of high quality, safe and sustainable quarantine arrangements.”

At no point is the state singled out for further praise, let alone awarded a fabled ‘gold star’.

Asked about this on Friday, Marshall insisted “we had direct feedback from the group that was doing the work”.

“There was very high praise for SA in terms of the way we managed our medi-hotels, but also the way we did our contact-tracing,” he said.

The Halton review had no remit over contract tracing, which was the subject of a separate national review that reported this month, headed by Australia’s Chief Scientist Dr Alan Finkel.

Asked whether his repeated claim to a gold star was thus verbal and informal, Marshall replied: “Correct.”

The wrong thing for me to put my mind to

The rhetoric around SA’s role in Australia’s quarantine arrangements shifted noticeably from Monday last week – the day Spurrier revealed the cluster had grown to double digits.

“I’ve had concerns over the last couple of weeks, not because of our processes, but just because of the number of positive cases we’ve had in those medi-hotels,” she told ABC Radio Adelaide that morning.

“It just increases the risk of it getting out, and it obviously has in this instance.”

While defending the robustness of the regime during Saturday’s media briefing, she noted that “regardless of that I could see that we were getting more and more positive people in our medi-hotels”.

“I know that’s our highest risk, and there are small things we can do to improve that system, but at the moment if I spent time going through that investigation [into the initial breach] – not to say that it’s not important – I wouldn’t be focussing on what I have to do now to prevent more infections in our state and that would be the wrong thing for me to have my mind put to.”

But the details of the initial case are crucial, given Spurrier’s initial emphasis on potential fomite transmission – an explanation that quickly gained traction in the Government’s rhetoric.

Despite his Chief Public Health Officer’s later insistence that reviewing the Peppers Hotel transmission was not a top priority, Marshall told parliament on Tuesday morning: “There is just simply no suggestion that there has been a [quarantine] breach, and that was the advice that I had been provided with.”

“The Chief Public Health Officer is extraordinarily busy at the moment, but it’s her opinion that the disease has probably been transmitted via a hard surface, rather than the traditional way that the disease has been transmitted, which is through close personal contact or aerosol droplets,” he said.

“If this is the case, then I suppose it opens up a whole body of other concerns that we have with regard to this disease.”

Spurrier still maintains this theory, saying as recently as Saturday that “we’re very concerned about how [the cleaner] may have acquired the infection”.

“We know with some infection that’s been acquired in similar situations in New Zealand, there’s been definite fomite transmission or surface transmission, inasmuch as that’s the only overlap that people can find in terms of being able to pick up the infection – there’s been no other face-to-face contact,” she said.

The ‘pizza box’ transmission theory that emerged when the Stamford Hotel worker told his infamous lie gave credence to the notion of fomite transmission.

The Spaniard initially told contact tracers he had simply ordered a pizza to be delivered. He later changed this story to say he had gone to Woodville to pick it up in person – a distinction Spurrier insists was “not material at all to my decision making”.

Stevens declined to answer whether the man actually lived in the Woodville area.

When it became clear the man instead worked in the pizzeria, and had spent considerable time there in recent days, the fear that potentially thousands of delivery customers may have been infected by fomite transmission eased considerably.

“Now that clearly this person actually works there, it would obviously be more of that person-to-person contact,” Spurrier said on Saturday.

“[As to] this question of how much does surface transmission count in terms of this particular virus, when you’ve got a lot of disease in the community and there’s lots of case numbers the majority of the transmission will be by droplet spread – two people being close to each other – but when you have very few infections, any form of transmission is going to be important… and that’s why in countries like Australia and New Zealand [where caseloads are low] we will have all seen cases of that.

“In countries such as Europe and the UK, they wouldn’t be having the opportunity or even the time to be looking at that sort of [surface] transmission.”

Midweek, she insisted while it was not as prevalent as person-to-person transmission, “there are very definitely cases of fomite transmission, or surface-to-surface transmission, where somebody who had infected secretions has touched another surface, and somebody else has touched it and then touched their face or eyes”.

“So we definitely know it can happen,” she said.

On Spurrier’s public statements, once the Stamford worker’s story changed, there was only one case in the Parafield Cluster still currently considered to have been contracted as a result of fomite transmission.

The first case.

Saturday, November 21

As the dust settled, on Saturday Spurrier announced one new case – a close contact of a previous case – but they were already in quarantine so, as ever, “they don’t pose any risk at all to the community”.

The cluster was now out to 26.

After the bluster of the previous day, Spurrier was keen to contextualise the lockdown decision – to suggest that, contrary to media reports, it wasn’t based on a single lie.

But those media reports were a direct reflection of the messaging from the previous day.

“The other thing that was obvious to me and my clinical team was that the incubation period was very short and we were seeing within 24 hours people able to infect other people, which meant the generations would be very short – it meant we had to move very, very quickly,” she said.

The following day, yesterday, she pushed on, showing a chart she said explained that the cluster could have led to a “50 per cent chance” of the infection growing exponentially, with SA a chance to reach 100 cases a day by the middle of December.

There was “a smaller but not negligible chance that we could have had an even higher caseload, upwards of 200 cases per day by mid-December”, she said.

“Really, to be clear, the decision to lock down hard – and I know it’s been very difficult for people in SA, and perhaps difficult to understand – was not based on the interview with one man… we would never make those decisions in isolation with just one piece of information.

“It’s very complex… if you wait too long, you have missed that opportunity.

“I was acting using that precautionary principle.”

It was the same principle urged by the World Health Organisation in March, when executive director Dr Michael Ryan famously said: “Be fast, have no regrets.”

“You must be the first mover. The virus will always get you if you don’t move quickly… if you need to be right before you move you will never win.

“Perfection is the enemy of the good when it comes to emergency management.”

Had this person been more upfront with us, we would not have instituted the six-day lockdown

Spurrier’s explanation was cheered by many in the online forums watching on, including some journalists – and even one network news director.

But Stevens wasn’t deviating from the simpler explanation.

“We’ve had intensive conversations with Professor Spurrier and other members of her health team [and] it is fair to say that had this person been more upfront with us, we would not have instituted the six-day lockdown,” he said firmly.

“But as the Professor has explained, this is like the straw that broke the camel’s back – this is the one element that pushed us from the level of restrictions we were implementing on Tuesday to a much harsher regime.

“We were in a position to control community movement as a result of the growing concerns around the Parafield cluster, but this one element is what you might describe as that one last piece of the jigsaw puzzle that pushed us into a decision point [where] we had to make that choice to impose those severe restrictions for a six-day period.”

But the previous day’s rhetoric – the Premier’s “fuming” about the lies, the desperation to throw the book at the Stamford worker – was dialled back.

Not for the first time, the messaging in the daily briefing was notably inconsistent.

Par for the course, perhaps, in a public health emergency.

Stevens was then asked whether subsequent events had changed his thoughts on medi-hotel workers taking on second jobs – questions about which he had so passionately derided two days earlier.

“Obviously I’ve reflected on the position and I’ve looked at the information that’s available to us – and I stand by my position that isolating an individual from one particular part of their private life without isolating them from all others is a simplistic view that doesn’t provide the level of comfort that people are looking for in terms of how we manage those people who volunteer to work in our medi-hotels,” he said.

Asked the same question, Spurrier noted “if you were to have all the staff in a medi-hotel not able to interact with the community you’d basically be quarantining everybody”.

But asked whether the state should consider increasing payments to ensure they did not need to seek further employment, she was more measured.

“I think all of those things can be examined – certainly, I would be advising that second jobs in higher-risk areas – and those are of course nursing homes, aged care, hospitals, correctional services – we should be avoiding,” she said.

“But it’s very difficult when you’ve got a casualised workforce and you’re expecting someone to just work part-time in one place, and obviously they need to have a full income.”

With all the incongruities, perhaps an independent inquiry – as occurred in Victoria – is the only way to clarify what went wrong in SA this week.

But as yet, few have called for one – not even the Opposition, which yesterday jumped that step and went straight to a demand that the medi-hotel system be scrapped and reimagined altogether.

Marshall did, however, say on Saturday that “there will be a thorough investigation” into the previous week’s events.

“But what we’ve said right from day one is this is a highly contagious disease – very senior trained nurses have come into contact and even with all of their PPE have been able to contract that disease,” he said.

“We know there’s a risk associated with every time we bring someone into this country – but we believe we need to play our part in repatriating these citizens.”

Then, yesterday, he added: “We’ve always said we’ve got a good system [but] we will have a review of this situation.”

“For every single incident under the Emergency Management Act, we conduct an independent investigation, so there will be a review which is done at that individual level as well as a larger review into that situation.”

The Act does not appear to contain any such stipulation.

Marshall told the reporter whose question prompted that commitment that he’d been saying as much consistently since the previous Sunday, suggesting that the journalist might have missed it because he may not have attended previous briefings.

It was, in fact, the first time he’d said it.

And the reporter had been there all week.

*The following week, after this article’s original publication, health authorities reviewed some CCTV stills from the Peppers hotel and declared that the cleaner was no longer considered the first patient in the cluster, but rather one of the two security guards.