Aboriginal mothers “absolutely helpless” after babies taken at SA hospitals

Aboriginal babies deemed at-risk by South Australia’s Child Protection Department are being removed from their mothers at Adelaide hospitals, not long after birth, in processes advocates say are unnecessarily cruel and opaque. Stephanie Richards talks to affected families.

SA Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People April Lawrie wants to investigate the statutory removal of Aboriginal newborns from the care of their birthmothers at hospitals. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

M had been in labour at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital for about one hour when she noticed a security guard standing outside her door.

The sight alarmed the Ngarrindjeri and Wiradjuri mother of seven, who was anxious about the welfare of her baby after a fraught pregnancy.

She had done all that she could to give her youngest son a safe start in life – including staying off drugs and eating a balanced diet – but despite her best efforts to care and protect him, nothing could prepare her for what was to come.

“I just had this bad feeling all of a sudden,” she says, recalling the events of December 6 2016, in the seconds after her son was born – healthy and crying.

“The nurse came in and was trying to put him on my chest and I noticed the police were looking in the room and the security with the red and white shirts.

“I could see my son was getting uncomfortable and I wanted to take him for a minute.

“I could kind of figure out what was going on.”

M wants her story told, but InDaily is unable to identify her due to secrecy provisions regarding children’s identities under the Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017.

The Murray Bridge local’s life has been significantly impacted by intergenerational trauma and loss of culture, stemming her own experience growing up as a child under the guardianship.

Prior to giving birth in 2016, M’s oldest children were at various stages made wards of the state and placed into foster and residential care homes, or sentenced in youth detention.

I’ve only seen him twice in his life

Her youngest son’s fate as a child under the guardianship was sealed months before he entered the world – deemed by the Government as being too at risk to remain in the care and protection of his birth mother, even before leaving her womb.

“After they took him I had tears in my eyes,” M says.

“They said he had jaundice and I just played along with it for a while because of the stress of the whole environment.”

The ensuing days were a blur for M, who started haemorrhaging shortly after giving birth.

She wasn’t sure where her baby was, or if he was OK – all she had was a photograph of her holding her son in the short moments they were together.

Three days after giving birth, M asked staff at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital if she could visit her son in the neonatal ward.

She’d been written-off pre-conception

A security guard and a nurse accompanied her to a separate room to see her baby, who seemed happy and healthy, but was due for a nappy change.

M asked if she could change him, but she says the request wasn’t well received.

“The security guard stood up and kind of glared at me and put me on show and made me feel really not like a mother.”

She says she asked to see the hospital’s Aboriginal liaison officer, but her request was declined.

“I handed him to my sister and I walked out and my aunty walked me back to the ward.

“There was eight coppers outside my door, three security guards and two DCP (Department for Child Protection) workers in my room.”

One of the child protection workers handed M a summons for a care and protection order, which stated that her baby needed to be removed from her guardianship and placed in the care of the Government.

“I didn’t want to argue with them,” M says.

“I kind of just shut out what she (the worker) was saying.

“It was just a blur.”

M says the Department for Child Protection did not tell her why her son needed to be taken from her, or placed in the care of a non-Aboriginal foster family.

The Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

She says she has a good relationship with four of her seven children, but the impacts of having them removed from her care has left her concerned about their understanding of Aboriginal culture.

“I’ve only seen him twice in his life,” she says, over three years after her youngest son was born.

“I’m trying to bring my family back together and I feel like I get so close to doing it, but it’s just frustrating.

“I feel like I failed as an Aboriginal woman, I feel like I am letting my community and family down.

“I just think, what if this is happening to so many other girls?

“How do I know that this has happened before but no one has told their story?”

“The cruellest thing you can do”

South Australia’s inaugural Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People, April Lawrie, was just two days on the job in late 2018 when one of her relatives told her that the Department for Child Protection had removed her baby.

She says the incident occurred at one of Adelaide’s three public birthing hospitals “through corroboration that occurred between the health staff and the DCP staff”.

To avoid identifying the child, she has chosen not to reveal the birthdate or birthplace – either the Women’s and Children’s or Lyell McEwin Hospitals, or Flinders Medical Centre.

“The baby was a little over two days old and she (the mother) was encouraged by the hospital staff – by the midwife – to have a cigarette, which goes against all the things about reducing smoking rates during pregnancy,” Lawrie says.

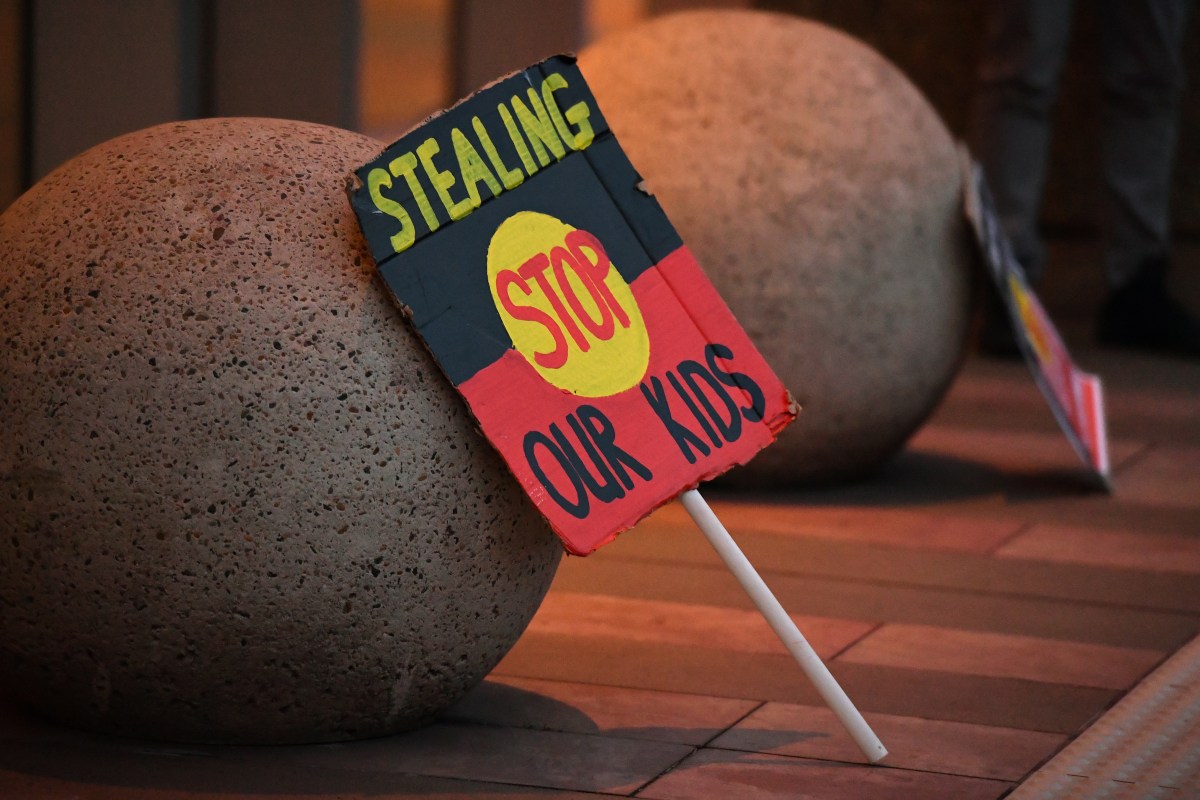

Photo: Joel Carrett/AAP

“She was thinking that this was weird, like the midwife wants me to smoke? They usually lecture you against smoking during pregnancy.

“She eventually went out to have a smoke – because she’s a smoker – but couldn’t understand the pressure to have her out the door to go and have a smoke.

“She returned to the ward to find her baby missing, to find that the hospital staff – including the midwife – wasn’t telling her where the baby was.

“Eventually she was that heartbroken that she actually walked out of the hospital because by the end of that evening no one would tell her where her baby was.

“She learned from an Aboriginal liaison officer that DCP had somehow been advised that she was having the baby and had made plans a long time ago that should she have any children, her baby would be removed regardless of what life-changing circumstances she might have had for the better.

“She’d been written-off pre-conception.”

Lawrie says her relative “did have historic contract with the Department” but she was not visited by a social worker during her pregnancy, or informed that the baby would be removed immediately following birth.

Most of our families don’t have the capacity to fight the system

The commissioner says since 2018, her office has been made aware of five separate instances of Aboriginal babies being removed from their mothers at hospital antenatal or birthing units across regional and metropolitan South Australia.

She says the practice is “racist” and leaves mothers “feeling absolutely helpless”.

“It’s the cruellest thing you can do,” she says.

“When I hear first-hand accounts and stories from mothers who have had their children removed, from grandmothers who weren’t informed, who weren’t involved in providing the immediate care arrangement for their grandchild, or to even be consulted or talked to, it just angers me so much.

“There probably are non-Aboriginal babies being removed but as far as I’m concerned with Aboriginal babies – particularly those born to Aboriginal mothers – the focus and the response by the child protection system is high impact.”

“There are thousands of horrendous stories like this”

Family Matters South Australia campaign coordinator Joanne Else has dedicated her career fighting to curb the over-representation of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care.

She says her phone “never stops ringing” from calls from Aboriginal mothers who have had their newborn babies immediately removed from their care at antenatal and birthing hospitals.

“There are thousands of horrendous stories like this,” the Ngarrindjeri woman says.

“Most of our families don’t have the capacity to fight the system.

“They don’t understand legislation, they don’t understand their own rights when it comes to this.

“It’s got to the point for the Aboriginal community where our young mothers won’t attend the hospital for antenatal because they know they’re going to be flagged.”

Else’s determination to fight the system stems from her family’s experience of having a baby taken into care when he was five-months-old.

We simply do not have systems that are adequately designed to support Aboriginal families

In the 10 months the child was away from his birth parents, Else says he was placed with 13 different families – most of them non-Aboriginal.

“The three of us – great-grandmother, grandmother, myself – all fought it,” she says.

“For the mothers, it sends them all over the place and it’s not just the birth mother, because we alloparent, so it’s an entire family who are affected by it.

“Every child needs to know who they are and for Aboriginal children, connection to culture needs to be a lived experience – a daily experience – not just some book that they give them to read every now and then.”

“Infants are being removed by statutory authorities almost without notice”

Child and Family SA CEO Rob Martin says the practice of removing Aboriginal babies from their mothers occurs not just in South Australia, but across the country.

In November last year, University of New South Wales law professor Megan Davis published a scathing review of the eastern state’s child protection system.

The review, which was commissioned by the NSW Government, found authorities were taking newborn Aboriginal children from their mothers in “flawed” and “unethical” ways, sometimes leaving mothers without any mementos or photographs.

Davis made 125 recommendations to overhaul the way Aboriginal families were treated by the system, including adopting new policies around newborns, a triage system that would identify women most in trouble during pregnancy and more prenatal caseworkers.

These are high-order issues that need to be addressed

A separate study published last year in the journal of Child Abuse and Neglect found Indigenous infants in Western Australia had been removed and placed into out-of-home care at ten times the rate of non-Indigenous babies.

In South Australia, about one third of newborns who are removed from the care of their parents within one month are Aboriginal.

“We know that nationally 37 per cent of all children in out-of-home care are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and they only represent 5.5 per cent of the total population,” Martin says.

“Although the primary reasons provided are a history of alcohol and other drugs or substance misuse, or the prevalence of domestic violence or the family’s remoteness, infants are being removed by statutory authorities almost without notice.

“We simply do not have systems that are adequately designed to support Aboriginal families – particularly in regional and remote communities – and the knee-jerk response of statutory authorities is to simply remove the children.”

Photo: Joel Carrett/AAP

In her inaugural report published in December, Commissioner April Lawrie wrote that there had been “limited” improvement in South Australia since the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission tabled its 1997 Bring Them Home report into the separation of Indigenous children from their families.

“Our state still has much to do to truly support Aboriginal families and to prevent another wave of the Stolen Generations,” her report stated.

Lawrie wants to launch a formal inquiry into the practice of removing Aboriginal babies from the care of their mothers whilst inpatients of birthing and antenatal care units, but despite already receiving compelling evidence, she says she is unable to conduct any investigation until her role is properly enshrined in legislation.

In 2018, InDaily reported that Education Minister John Gardner had decided to scrap a draft amendment to the Children and Young People (Oversight and Advocacy Bodies) Act, outlining the proposed role of the Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People.

He instead fast-tracked Lawrie’s appointment via a clause in the Constitution Act – leaving her without any defined statutory authority.

“There’s nothing that compels them to actually listen to me,” Lawrie says.

“I can have regular meetings and I can go out and say something, but unless there is a formal enshrinement of this role in legislation and I do a formal inquiry that Government has to respond to… I don’t think much change will happen.

“These are high-order issues that need to be addressed.”

In a statement to InDaily, Gardner said he intended to bring a Bill to parliament this year to entrench Lawrie’s role in legislation – two years after she was appointed.

“We are proud to be the first government in South Australia to create the role of Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People, and we worked swiftly to make that appointment so that this work could begin as quickly as possible,” he said.

“Current arrangements have enabled the commissioner to undertake critical oversight functions, but this Bill will entrench this role and its functions alongside other oversight and advocacy bodies.”

Children have the right to be placed in caring environments

InDaily asked the Department for Child Protection to respond to both M and Lawrie’s experiences of having family members placed into care.

A spokesperson said the Department was bound by confidentiality to not discuss the circumstances of individual matters, however it “acknowledges that the removal of children to keep them safe can be highly distressing for family members”, particularly for Aboriginal families due to the historical and intergenerational impacts of the Stolen Generation.

“There are occasions when DCP is required by law to intervene to protect newborn infants,” the spokesperson said.

“When this happens, we are committed to being transparent with both the parents and extended family about our concerns.”

The Department’s deputy chief executive Fiona Ward says unborn children can be flagged with authorities if their parents suffer significant mental illness, if they engage in substance misuse, or are exposed to family violence and there is a genuine concern for the safety of the child.

“High-risk infant workers” are stationed in all three metropolitan birthing hospitals to help staff identify expectant mothers who are at risk of requiring child protection intervention, and to encourage antenatal care, family meetings and culturally-appropriate support to mothers.

The Department has also introduced a family group conferencing program this year to ensure “appropriate and meaningful engagement” with extended family members occurs regarding a child’s welfare.

I wonder what he looks like everyday

“A decision to remove a child or young person from the care of their parent(s) is a decision of last resort,” Ward says.

“DCP staff are committed to working with biological parents and extended family members to prevent removal when it is safe to do so.

“If placement away from biological parents is necessary, the child has a right to be placed in a caring environment that meets his or her needs, preferably with kin.”

But M, who is fighting to be allowed to visit her now three-year-old son, says the Department needs to do more to involve Aboriginal communities in decision-making about the care of their children.

“I wonder what he looks like everyday,” she says.

“They gave me one baby photo but not ones from when he was big.

“When you destroy the family, you destroy the community and society.

“My dreaming and culture are so important to me and it’s getting lost through my babies.

“It haunts me everyday.”