The ‘sin’ of simply being yourself

The heartwrenching television series It’s a Sin has evoked memories of the AIDS epidemic in Adelaide, when young men died and were commonly buried in rejection and shame. Simon Royal wonders if the real, terrible, sins of that time can be remedied.

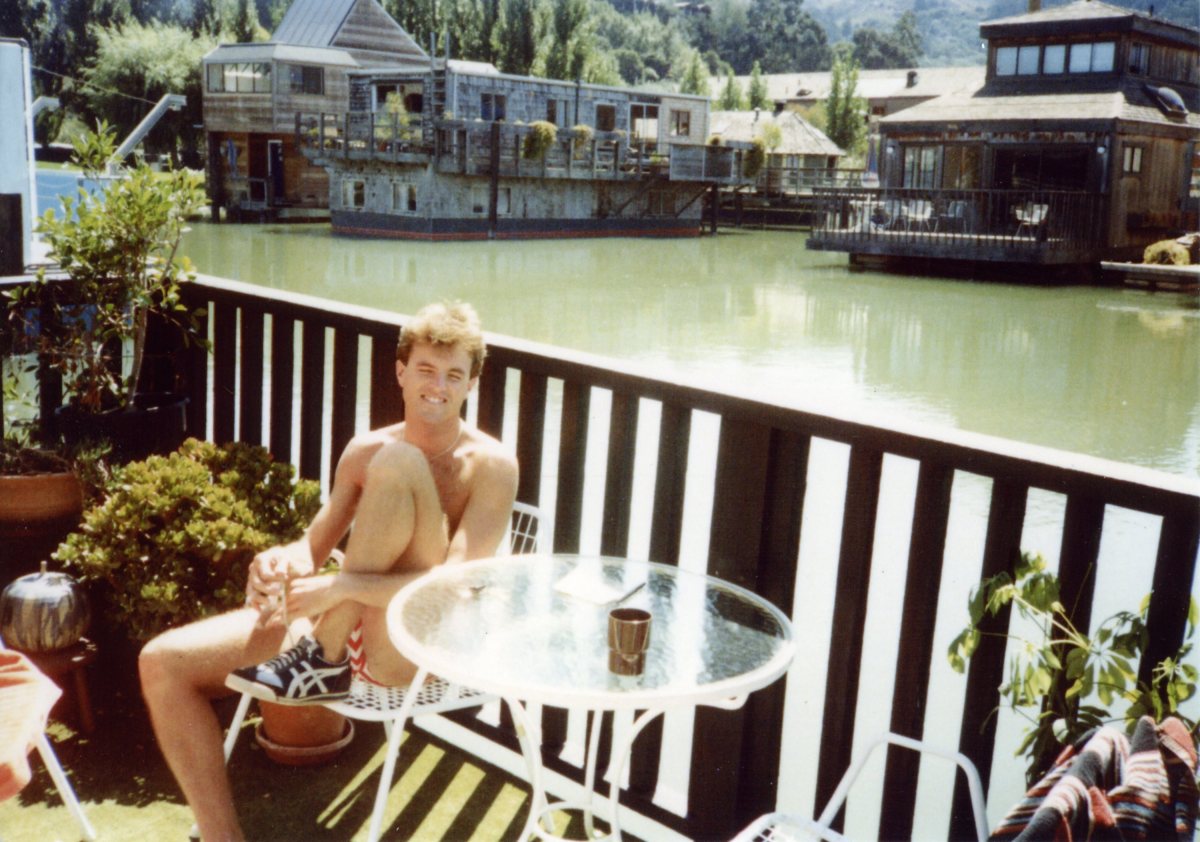

"What killed Das certainly wasn’t named, showing AIDS was capable of still spelling shame well after it had spelt death." Das at a hotel in San Luis Obispo, California, in 1983. Photo by Len Amadio

It was one small word. In fact, not even a word in its own right. Just four letters – AIDS – the acronym for acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Together, though, those letters wielded a power far beyond their modest number. Throughout the 1980s they spelled many things – fear, shame, rejection. The words tumbled on, including the one which made AIDS into a sentence: death.

There was no bargaining with it. If you got it, it would kill you, or so it seemed. But only after first visiting those other words upon you: fear, shame, rejection…

Forty years ago, in June 1981, odd reports began filtering out from San Fransisco and New York of young, previously healthy gay men dying of rare illnesses. Initially, the experts didn’t call it AIDS, preferring the term G.R.I.D. – gay-related immune deficiency. Doctors were alarmed that the diseases they were now seeing in these men were usually found exclusively in old people, or those with severely compromised immune systems.

Knowing the names and symptoms swiftly became second nature: Kaposi’s sarcoma, with its telltale reddish-brown spots, pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, with its chills, cough and shortness of breath. It didn’t matter if you knew, rationally, that your chances of having being exposed to the virus were slight. Every new bruise or blemish was mercilessly interrogated, poked and prodded until it grew angrier, and redder, and more of a worry. Slowly it would subside, until the next one came along and the cycle repeated itself. More self-destructive, though, than wondering whether you’d caught it was wondering whether, at some small level, you might actually deserve it.

There were a handful of cases to begin with. Then, as we’ve seen with coronavirus, the graphs ticked upwards. On and on they climbed, sweeping from the territory of medical curiosity into full-blown epidemic.

The religious right considered it a godsend. A virtuous circle of proof, whereby their belief God should smite the gays was borne out by God, apparently, smiting the gays. But churches, by no means, had the market cornered in casual cruelty. People lost their jobs, their friends, their families.

At Kincumber, on the New South Wales Central Coast, a little girl named Eve van Grafhorst was hounded out of her kindy, and then her home, when people discovered she’d acquired the virus through a blood transfusion. Eventually, when the western world looked beyond itself to Africa where the disease originated, we found it was characterised there by heterosexual transmission. It turned out that HIV, the virus which causes AIDS, was just in it for the sex – gay or straight. The virus didn’t ever discriminate – that symptom was all on us.

Russell T Davies, the Welsh screenwriter and TV producer, has taken those themes of the unfolding AIDS crisis and fashioned them into his latest production – a five-part series named for the Pet Shop Boys’ ’80s anthem, It’s A Sin (now streaming in Australia on Stan). The storyline revolves around five young people sharing a house in London.

It’s hardly the first biopic to follow the disease as it scythes through the lives of its characters. There’s Tim Conigrave’s beautiful, heartbreaking, Holding the Man, and the 1989 film, Longtime Companion. But something about Davies’ effort is different, for me at least. Despite being set on the other side of the world, It’s a Sin hits close to home.

It’s made me think of things I haven’t thought of in years. It’s reminded me of people I’ve never forgotten but who, by the same token, I’ve never properly remembered, either. It’s the character of Colin, played by 21-year-old Callum Scott Howells, that does it. He’s so much like someone I once knew.

In Davies’ film, Colin leaves his life in a small village in Wales and comes out in London. He finds friends, finds a job, gets sacked, and finds a better job. Colin is quiet, reserved and unfailingly sweet. The boy I knew shared those qualities with Colin. They even shared part of their name. Michael Collins was the boy I knew. In 1984 he was my friend Mark’s latest romance.

Michael was the kid from the northern suburbs Housing Trust home who’d made it to medical school. He worked so hard. After finishing his intern year Michael’s dream, like Colin’s, was to go to London. And like Colin in the film, Michael, too, went to Heaven nightclub. He spent a year in London. It was there, so Mark tells me, that Michael contracted the virus. I don’t even know if he lived until his 30th birthday.

Forgetting those times would be the real sin.

The stories of both the on-screen Colin and the real-life Michael sum up the capricious nature of who got the virus and who didn’t. There were men who lived like there was no tomorrow, who are still alive today. Some dodged the bullet, never picking up the virus. A few HIV-positive people, through a quirk of genetic makeup, survived until effective treatments arrived. Some of them are still with us today, having exacted the best revenge on an implacable foe – they lived.

Other young men whose lives had barely begun, like Michael, got it and died. That sentence seems to invite the phrase, ’he made just one mistake’, but I won’t use it, or think it. What was their mistake? To have met someone they liked and then had sex? To have been who they are? To have gone to London? I know Mark still occasionally wonders what might have been if he hadn’t encouraged Michael to go. There’s absolutely no point to any of those ‘what ifs’ or ‘if onlys’. They never offer understanding, only judgement or heartache.

Some people were lucky, others weren’t. It was inexplicably, unremittingly unfair, and nothing more.

Later in the ’80s, I joined the AIDS council as a volunteer. We were assigned to HIV-positive people to support them, which was usually nothing more demanding than catching up for coffee and offering some company. I’d met Das – short for David Arthur Stewart – some years earlier, a bit before starting university. He was eight years older than me and already working. Das was Michael’s polar opposite – loud, confident, and completely comfortable being the centre of attention. And funny, he was very funny.

Das had gone to Los Angeles in 1981 to do, I think, his MBA. In late 1987 he’d returned home to Australia to die.

Das was loud, confident and very funny. Photo by Len Amadio in Sausalito, California, 1983.

For a month or so I visited him a few times a week in the RAH. The details of just one of those occasions stand out from the haze now, and even it doesn’t seem quite real. It’s been so long since I’ve thought of it. It was the only time Das was well enough to leave the hospital with me. He wanted to walk across Frome Road to the Torrens, and so we set off on one of those clear blue Adelaide summer days. I remember beds of canna lilies, the deepest most exuberant shade of red, on the river banks. The lilies seemed to throw themselves at the bright sun. Those flowers were the epitome of what the frail man holding my arm for support was like in his prime. I suppose we stopped to sit and talk. I know we had to pause often because Das was too weak to make it in one go. Not long afterwards he lost his sight in one eye. Maybe it was both, I can’t be sure now. Soon, he was dead.

I remember the day of the funeral. Unusually for February, it poured with rain. I borrowed Mark’s elderly Fiat 124 to drive out to Centennial Park cemetery for the service. Being crafted from pre-rusted Russian steel, the Fiat leaked prodigiously, with left-hand corners, in particular, leading to water cascading into the cabin. The journey resembled a strange and damp folk dance – turn and duck, turn and duck – the whole way there.

In the chapel, people sat as though it were a wedding, with the groom’s folk to one side, and the bride’s on the other. Except this was a funeral for someone who’d died of AIDS, so it was straights up the front, gays to the rear. If nothing else time has lent an element of black humour to those seating arrangements.

I remember feeling deeply awkward and uncomfortable, but unlike the funeral scene in It’s a Sin, there were no angry confrontations. That’s because no-one really said anything at all. What killed Das certainly wasn’t named, showing AIDS was capable of still spelling shame well after it had spelt death. The silence though, I suspect, came from a sense that what had really caused Das’s death wasn’t so much AIDS, as it was his sexuality. And there we were, friends and volunteer supporters, in the chapel, at his funeral, committing the twin sins of being alive and gay. It’s not as though there weren’t things to say, even if they sounded like the standard funereal niceties – your son was so brave, he was so clever, he was such fun – and so on. There was plenty to say, it’s just we didn’t know how to speak to one another. Family versus friends, gay versus straight. It was a great divide, of which none of us had the faintest idea of how to bridge.

Callum Scott Howells as Colin in It’s a Sin. Photo: RED Production Company/all3media international

Once, all of this was my generation’s constant companion. To someone born in the 1990s, it’s a tale from a distant time. A few days ago I spoke with a young friend who’d binge-watched It’s a Sin.

“I didn’t know those reddish-brown spots were a sign of the disease,” he said. And why would he know?

Thanks to astonishing advances in science and medicine AIDS has been knocked down to size. It’s even lost a letter. Today we speak almost exclusively of HIV, rather than AIDS.

New treatments and prophylactic drugs mean people, if they actually get the virus, no longer march to the point where their immune system is so ravaged they die. HIV is not a sentence – it’s a manageable condition, like diabetes. The departure of that sentence has seen a whole miserable lexicon vanish along with it. We no longer hear of ‘AIDS carriers’, or ‘AIDS sufferers’, or ‘innocent victims’ – those who got the virus through blood transfusions, rather than sex or drugs. We don’t hear of the gay plague.

There are things we no longer see, too. Healthy young men don’t inexorably waste away, until they become so frail and haunted-looking they need to hang off someone’s arm to shuffle down a street. And there are places we no longer go. We don’t drive leaky cars through the rain to go to young men’s funerals.

Dozens of words can describe what these changes mean, but a straightforward one does it best – good. My young friend, the one who didn’t know what Kaposi’s sarcoma is, can live and love without fear – good. He doesn’t have to know the names of god-awful diseases off by heart – good. Sex won’t kill him – good, because that’s how it should be for a 20-something. For that matter sex won’t kill me either unless, at the age of 58, it’s through the sheer shock of it happening – good also, I guess.

If we live long enough tragedy inevitably morphs into entertainment. Or worse, an anecdote. There’s nothing inherently wrong with It’s a Sin functioning at that level, especially for an audience that wasn’t around for the events it depicts. Forgetting those times would be the real sin.

But beyond anecdote, it now strikes me that we have unfinished business with the people who did live through AIDS, and, of course, those who didn’t. Human history is punctuated by events that kill scores through no fault of their own. Our plague year, 2020, should have reminded us of that.

The people who died from AIDS are no different to those who died of some other untreatable disease – bubonic plague, typhoid, cholera, and yes, COVID. Too often fear smothered our humanity during the AIDS crisis, but I believe we are kinder now than we were back then. And even if we aren’t, we can choose to be.

If we make that choice, then those of us who didn’t know how to speak could talk to those who didn’t know how to hear.

We could say the sort of things that should have been said in a chapel 30 years ago – a conversation perhaps like this: “May we talk about your boy, please? He was clever, and funny too, wasn’t he? He was so, so brave… and we were lucky… very lucky… to have known him.”

Simon Royal is an Adelaide journalist.

It’s a Sin is available to stream on Stan.