The extraordinary life, and lonely death, of a writer

Marsha Mehran was a prolific writer and bestselling novelist before her lonely death at just 36. Andrew Hunter explores her life and legacy, including her little-known time in Adelaide – one of many stops across the globe for the Iranian refugee as she searched for a place to call home.

A quarter of a century and a lifetime ago, I shared an Adelaide bus home from school with someone who dreamt of a career as a concert pianist. At the time, she exuded confidence, and other identifiably American characteristics. She once announced in front of a school assembly in a lyrical, American accent, that “hip hop hooray” would be the theme of the upcoming school “prom”.

After high school, Marsha Mehran pursued her dreams at the Elder Conservatorium of Music. When next I heard news of her from fellow classmate (and now InDaily journalist) Tom Richardson, the year of the 20th anniversary of high school graduation, she had died.

In the intervening years, Marsha had, on the surface, lived the sort of life of which I regularly daydream. She was a novelist published in 15 languages and 20 countries. Her debut novel, Pomegranate Soup, was an international bestseller. But, according to media reports from Ireland, Marsha died in 2014 in a small town in the country’s west, a 36-year-old recluse suffering from mental illness, while trying to finish her third novel.

When Marsha was found, she had been dead for over a week. The autopsy failed to identify the cause of death. A broken heart is hardly a scientific diagnosis.

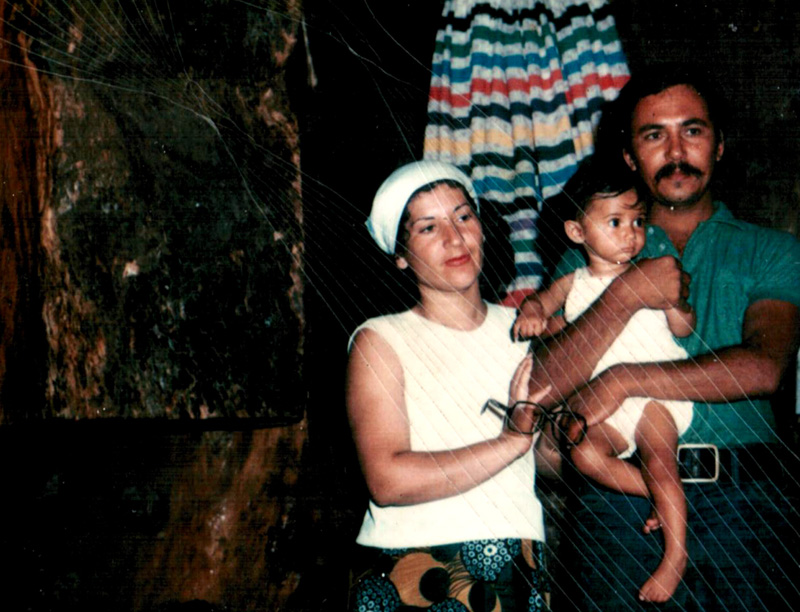

Marsha’s life was an incredible story, lived in a series of exotic settings. Her nomadic existence should not imply lack of interest in finding a place to call home. Her parents both practised Baháʼí Faith, considered a heresy in Iran, where Marsha was born. Immediately after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the Mehran family moved to Argentina. Before long, they moved again, to the United States, a country in which her prodigious talent was recognised. It was the only country where she felt at home.

Marsha Mehran as a young girl with her parents. Photo: marshamehran.com

Marsha’s literary output was intertwined with her life experience. Pomegranate Soup and its sequel, Rosewater and Soda Bread, tell the story of three Iranian sisters who escaped the Islamic revolution to Ireland, where they established a café in a small village in country Mayo. The village, “Ballinacroagh”, was fictitious but the narrative mirrored Marsha’s personal journey from Tehran, the city of her birth, to County Mayo, where the premature ending to her own story was written.

Her posthumously published book (her father, Abbas, completed the final drafts), The Margaret Thatcher School of Beauty, was set in the city to which her family fled the Islamic Revolution – Buenos Aires. It’s about a group of Iranian refugees, one of whom opens a beauty salon in Buenos Aires, which becomes the venue for weekly readings of Persian poetry. This strongly echoes the actual experience of the Mehran family, who shared Persian poetry and food, and provided band andazi (hair threading) to customers of the café (El Pollo Loco) which they established in their rented apartment in the city in the early 1980s.

Marsha’s books celebrate Persian culture.

Common themes unite the three books: displacement and new beginnings, cultural expressions that transcend time and place. The books elevate and celebrate expressions of Persian culture. Pomegranate Soup and Rosewater and Soda Bread were replete with vivid descriptions of Persia’s distinctive gastronomy, while Marsha’s third title focussed on Persian poetry.

Marsha’s stories invite a deeper intercultural understanding, both within and through her writing, which invites participants to reimagine Persia for the richness of its culture rather than its adherence to Islam. I became aware of her books only after her death, but reading them gave me a sense that the fusion of fiction and biography was an attempt by a young writer leading a life of perennial displacement to find an emotional mooring to her itinerant existence.

In a conversation recently, Marsha’s father Abbas, himself an artist, described how she was placed in a program for exceptional students in Miami. From the age of 11 years, Marsha avidly read Tolstoy. War and Peace and Anna Karenina were favourites. Abbas was convinced at this point she would be a writer. Her parents divorced, and Marsha moved again: to South Australia, where she attended Marryatville High School then briefly the University of Adelaide.

When Marsha died, many tried to claim her as their own. She was often described as Iranian, but others rejoiced in the time she spent variously in the United States or Ireland. Few people referenced her time in Australia, a country to which she returned following another brief stint in America, even though it was a formative period in her life. Abbas wondered whether our reluctance to claim Marsha was a consequence of “tall poppy syndrome”, but in truth, she rarely referred to Australia in media interviews.

Marsha found in America a home. Within the US, Brooklyn, where she arrived as a 19-year old to work in a restaurant run by members of the Russian mafia, was her spiritual home. Yet despite her devotion to America, she was denied permanent residence. When I spoke to him, Abbas queried whether the timing, in the early years of the war against terror, explained why someone of Iranian heritage was denied a visa. It is inexplicable that a country that considers itself great would condemn a person to statelessness.

Spiritual home: The author with her dog in Brooklyn in 2005. Photo: marshamehran.com

Marsha moved to Ireland, a continuation of a life in exile. America’s rejection broke her spirit, a situation made worse by her inability to realise a standard of artistry she deemed acceptable in her third novel. According to her father, Marsha worked on the novel from 2008 to her death in 2014, 20 years after our shared bus journey. She was found lying in vomit in a dishevelled cottage in western Ireland. A sign on the front door of her rented, modest, and isolated residence read: “Do not disturb: I’m working.”

Since I became aware of her extraordinary life, and death, I have thought a lot about this person, with whom I was briefly acquainted, but hardly knew at all.

In the intervening period, I have visited the country of her birth twice and studied its language. Such was my admiration for her literary hero, Tolstoy, I once named a dog after him. And now, I have accepted an invitation to sit on the advisory board of the J.M. Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice, which aims to bring together literary and musical (as well as multimedia) scholars and artists – a connection with Marsha which I’ll explain.

Marsha chose writing over the pursuit of her initial goal of being a concert pianist, and her writing maintained a lyrical quality. Her lyrical style fitted nicely into the arc of her personal story. She was both a natural writer and a trained musician, and it is the easy fusion of both genres that gave her work its accessible, poetic character.

Marsha at her desk. Photo: marshamehran.com

The transcendence of music and literature is not a new idea, and many renowned novelists found their first love in music, not least Franco-Czech novelist Milan Kundera, who has reflected deeply on this connection. Haruki Murakami ran a jazz bar – Peter-Cat – and liked to listen to jazz as he read novels, before himself becoming a novelist. Polyphony was a technique deployed by Coetzee.

Like Marsha, Coetzee was also denied a visa to reside in the United States, which was believed to be a consequence of his active opposition to the Vietnam War. This latter rejection was not fatal, and Coetzee has been embraced as a South Australian. His connection with the University of Adelaide is a wonderful thing. Our tendency for self-deprecation could explain any reluctance to celebrate this special connection.

In one piece she wrote for The New York Times Magazine, Marsha referred to the warmth of her Australian schoolmates, but otherwise described a lack of mooring in a “pale, homogenised culture”, which may be more a reflection of an experience of Australia limited to Adelaide’s eastern suburbs than of Australia itself. Australia was not the only country which failed to satisfy Marsha’s search for her place in the world: with Iran, Argentina, the United States and Ireland, Australia was one stop of many.

Marsha’s work suggests Persian culture provided a metaphysical anchorage in the absence of a place she was allowed to call home. But the essence of Marsha’s life remains elusive. Hers is a story of a person whose spirit breezed across continents, countries, and contexts without ever being allowed to settle.

A shooting star, a mystery, a tragedy. A life worth remembering.