Diary of a Bookseller: Everyone’s talking about this

This month’s recommended reads include the much-talked-about new debut novel by bestselling Priestdaddy author Patricia Lockwood, an incisive Australian young-adult story, a memoir of racism and resilience, and a heartfelt rock ‘n’ roll tale.

“I’m a book mogul!” joked the customer as she reappeared at the counter for her second purchase in five minutes. She’d been unable to resist a $5 book bargain on her way over the border from the bookshop to Hindley Street.

“Then what am I?” I said, gesturing at a tall pile of books I’d gathered to take home. She laughed.

Top of my to-read pile this month was Patricia Lockwood’s newly arrived “internet novel”, No One is Talking About This (Bloomsbury, April). I’m not the first one to make the joke that, in fact, everyone is talking about this debut novel by the world-bestselling author of Priestdaddy, Lockwood’s loving comic memoir of growing up in rectories across Midwestern America as the daughter of a gun-loving, guitar-worshipping, action-movie-binge-watching Catholic priest, who slipped through the celibacy loophole by converting to Catholicism as a married Lutheran priest with a family. (And yes, if this sounds familiar, she was a guest at Adelaide Writers’ Week in 2018.)

No One is Talking About This is a novel in fragments. Like Jenny Offill’s brilliant Weather, it’s told through a series of often-poetic curated moments and observations. But the voice and humour of this novel is stranger, more uniquely itself, and it’s more myopically focused on its subject of “the portal”, its form mirroring social media’s endless scroll. On Twitter: “Every day their attention must turn, like the shine on a school of fish, all at once, toward a new person to hate. Sometimes the subject was a war criminal, but other times it was someone who made a heinous substitution in guacamole.”

No One is Talking About This is a novel in fragments. Like Jenny Offill’s brilliant Weather, it’s told through a series of often-poetic curated moments and observations. But the voice and humour of this novel is stranger, more uniquely itself, and it’s more myopically focused on its subject of “the portal”, its form mirroring social media’s endless scroll. On Twitter: “Every day their attention must turn, like the shine on a school of fish, all at once, toward a new person to hate. Sometimes the subject was a war criminal, but other times it was someone who made a heinous substitution in guacamole.”

The main stage is the poet-narrator’s life online, where she is celebrated for her uncanny affinity for the ever-evolving language of “the portal” after shooting to international fame with a Twitter post that read, Can a dog be twins?. Then her sister’s unborn child is prenatally diagnosed with a rare fatal disease. “If she lived, they did not believe she would live for long. If she lived for long, they did not know what her life would be – she would live in her senses.” And with that, the narrator’s life is turned inside-out; the weight of her focus shifts from the portal to the physical, sensory world, in a way that recalibrates her perspective even after the crisis has passed.

But No One is Talking About This is not an anti-internet novel. While it catalogues the absurdities and eerie disconnection within the portal and online subcultures, it also celebrates its genuine community, and the joy of immersion in a world where words so urgently define experience. It’s smart, funny, beautiful, weird, and deeply touching – and I can’t see another novel this year grabbing me so completely.

The Gaps (Text, March), Leanne Hall’s sharp, incisive, voice-driven third YA novel, revolving around the abduction of a high-school girl, is another novel that I can’t stop thinking about, or recommending. The novel opens with the abduction of 16-year-old Yin Mitchell, a student at the exclusive Balmoral Ladies’ College.

Scholarship student Chloe, still a “new girl” six months into her time there, watches it unfold on the TV news, and at school the next day, “the whole year level is infected” and social boundaries temporarily blur as students swap gossip, fears and theories about what might have happened. Acerbic queen bee Natalia, leader of The Blondes (reminiscent of Mean Girls’ Plastics), alternates narration with Chloe, and an unlikely connection emerges between her and orchestra nerd Yin. The characters and suspense are what kept me turning the pages at speed to find out what happened – though I suspected I might never learn what happened to Yin, I couldn’t tear myself away until the conclusion.

Scholarship student Chloe, still a “new girl” six months into her time there, watches it unfold on the TV news, and at school the next day, “the whole year level is infected” and social boundaries temporarily blur as students swap gossip, fears and theories about what might have happened. Acerbic queen bee Natalia, leader of The Blondes (reminiscent of Mean Girls’ Plastics), alternates narration with Chloe, and an unlikely connection emerges between her and orchestra nerd Yin. The characters and suspense are what kept me turning the pages at speed to find out what happened – though I suspected I might never learn what happened to Yin, I couldn’t tear myself away until the conclusion.

But The Gaps is less about solving the mystery than exploring the effect of this sudden violence on its community, and our complex relationship with dead-girl narratives – and what they reveal about us as a society. Chloe’s crime-fiction addict mother explains that they’re probably using an old school photo of Yin to make her look younger, cuter, more sympathetic. “It’s bleak, but she’s Chinese, and already some people might not care as much. The more the public relates to a victim, the better.”

Both Chloe and Natalia can’t help but notice the glamorisation of a similar circumstance in Devil’s Creek, a popular new prestige series (strong echoes of Twin Peaks) in which the missing girl is the perfect victim. And an art project offers an opportunity for them to express their own complex feelings about Yin’s disappearance, and the fears it evokes. There’s so much in this clever, addictive novel, and it will appeal to readers of all ages. Fans of Megan Abbott and Alice Bolin’s Dead Girls should snap this up.

Veronica Gorrie’s Black and Blue: A Memoir of Racism and Resilience (Scribe, April) is the powerful, revelatory story of an Aboriginal woman who worked as a Queensland police officer for 10 years before resigning, broken by the system. “Policing fucked me up big time,” she writes. “You either conform to become one of them and allow yourself to be part of the racist system and their racist ideologies about your own people, or you are in a constant battle, defending yourself.”

Gorrie writes about her efforts to change the system from within, inevitably educating her fellow officers about Aboriginal culture (and rightly resenting it) and taking the time to build relationships in her community and treat offenders like human beings (which helped her police work as well as being an ethical way to behave) – while also reflecting on the ways she was co-opted, and behaviour she’s now ashamed of. Her complex reporting from the inside, capturing the culture of police work and providing empathetic insights into the communities she policed, is sometimes reminiscent of The Wire, if told from the perspective of a black woman who’s experienced generational disadvantage, poverty and domestic violence.

Gorrie writes about her efforts to change the system from within, inevitably educating her fellow officers about Aboriginal culture (and rightly resenting it) and taking the time to build relationships in her community and treat offenders like human beings (which helped her police work as well as being an ethical way to behave) – while also reflecting on the ways she was co-opted, and behaviour she’s now ashamed of. Her complex reporting from the inside, capturing the culture of police work and providing empathetic insights into the communities she policed, is sometimes reminiscent of The Wire, if told from the perspective of a black woman who’s experienced generational disadvantage, poverty and domestic violence.

Black and Blue would be an extraordinary read just on this basis – but what makes it something truly special is that Gorrie’s experience as a police officer is contextualised with her life before the police force, which takes up the first half of the book. She writes about her childhood with her Aboriginal father – a man who has always been there for her – her alcoholic white mother, and her three brothers and sisters. Her mother was violent, and her father left when she has seven, returning to take custody of his children soon after. Her childhood was itinerant, moving between various configurations of the family unit, and in and out of safety and danger, particularly when she stayed with her mother.

Gorrie was one of just seven Aboriginal students to graduate Year 12 in Victoria in 1988, and went to university. Her life was seriously derailed when she found herself in an abusive relationship, in which she came close to being killed, and had to leave the state to get away. But her story is also rich with love and an empathy for the family members, like her mother, who let her down. It is also woven with the legacy of dispossession and institutionalised colonialism, from forced removal of children (her grandmother was one of the stolen generations) to police profiling now.

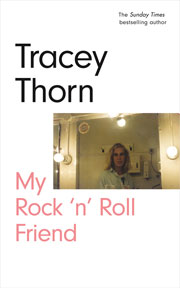

Another memoir I’ve read and loved this month was Tracey Thorn’s gorgeous, funny, heartfelt My Rock ’n’ Roll Friend (March, Canongate), about her best friend Lindy Morrison, drummer of cult classic Australian band The Go-Betweens (1977-1989). Thorn, the vocalist for UK band Everything But the Girl, writes: “You’re a drummer and I’m a singer, but we read, we like films. We complain about men, desire men, move in a world of men. I feel like I’m following you, like you’re my sister.”

The book was sparked by Morrison’s marginalisation in histories of the band, which typically characterise it as Robert Forster and Grant McLennan, with added extras. And while it has fascinating backstage insights, including anecdotes of sharing a house with Nick Cave in London (Lindy was the only one not on heroin, and with a day job, for which she was mocked as unserious), it’s primarily a tribute to female friendship, a record of being women together in a sexist music industry, and a portrait of a passionate, big-hearted artist.

The book was sparked by Morrison’s marginalisation in histories of the band, which typically characterise it as Robert Forster and Grant McLennan, with added extras. And while it has fascinating backstage insights, including anecdotes of sharing a house with Nick Cave in London (Lindy was the only one not on heroin, and with a day job, for which she was mocked as unserious), it’s primarily a tribute to female friendship, a record of being women together in a sexist music industry, and a portrait of a passionate, big-hearted artist.

Lindy was also a trained social worker who worked for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service in Joh’s repressive, racist Queensland, and a music therapist after she was dumped from the band. And while the book can be scathing about Robert and Grant (described as “the kind of boys who buy Playboy magazine for the Bob Dylan interview inside”), it’s also loving about the passionate long relationship between Robert and Lindy, which is surprisingly present in many songs. Highly recommended with musical accompaniment: I read it while listening to the Go-Betweens box-set I bought for my husband (really! not for myself!) last Christmas.

Or if your musical tastes, like my colleague Jason, run more to Bob Dylan, then you’re also in luck. He’s been spending his spare time listening to his Dylan records while reading The Double Life of Bob Dylan: Volume 1, 1941-1966, A Restless Hungry Feeling (Bodley Head, HB), and tells us all that it’s amazing.

Jo Case is a bookseller at Imprints Booksellers on Hindley Street and an associate publisher at Wakefield Press.