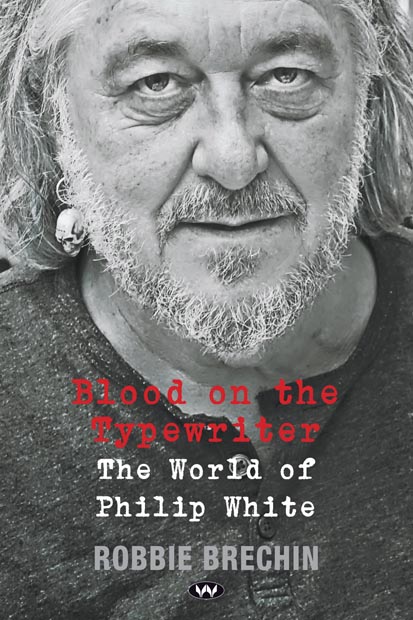

Book extract: Blood on the Typewriter – The World of Philip White

In a “gonzo” biography published today, Robbie Brechin unpacks the large and unconventional life of South Australian wine writer Philip White.

‘I’m not here to be popular.’

– Philip White, ABC Radio National, 10 June 2011

What makes some experts say Philip is the best wine writer in Australia and among the cream of the rest of the world? First and foremost, he owns what might rudely be known as a great big ‘blob’. We all have millions of receptors in our noses, via the olfactory bulb, a blob of nervous tissue where the brain joins the nasal passage. Not very romantic. Far from the popular image of Philip as a towering poet–pirate with boots of Spanish leather and a mesmerising way of storytelling. His nose is a gift and puts him in the same unearthly league as a bloodhound, which can still follow a perfume trail 300 hours old. For the rest of us, that scent disappears in a few minutes. (The king of the animal ‘noses’ belongs to the African elephant, which combines that blob with a more than handy memory.)

If Philip were simply an in-depth, supernaturally knowledgeable examiner of wine, with all the fine phrases and technical nous, he really would be a footnote. Obvious hallmarks of Philip’s character are authenticity, integrity, refusal to bend to commercial or self-interested pressures. But what elevates him, distinguishes him from the crowd, is courage. His battlefield bravery is admired by friends and enemies alike. The courage is linked to truth. You may not agree with the fire and brimstone preached by Philip’s pastor father Jimmy, but Jimmy believed in its veracity.

Philip has never been afraid to live a life off the grid. The Kanmantoo Kid was never going to settle down with a wife and three children on a quarter-acre block; regular job, suit and tie. Not for him a ‘lifestyle’ that has been all but pre-destined, with safety rails and Treasure Island superannuation. More the Neil Young philosophy that life in the ditch can be a lot more stimulating than in the middle of the road.

‘He’s lived by his own rules,’ filmmaker Gus Howard says. ‘He’s suffered for it and he’s had a lot of pleasure from it and he’s given a lot of other people pleasure.’ Howard says businessmen with an artistic yearning can’t simply be artists – they have to build empires, which provides a life with an easily discernible pattern.

Philip has constantly been writing and rewriting and living his stories. As much as he likes an audience, he creates a wilderness for himself. He’s the sort of person who would get a train up to full speed, racing through the night. Jumped out of a lot of runaway trains and cars in his time and been saved because he usually knows when to jump. But there’s a litany of self-destruction. So every time he hasn’t timed his exit right, it’s given him a scar.

He’s a very masculine person and men are biologically designed to be self-destructive. So here is a guy who is a stand-up mystical poet. Intelligent, capable, articulate – and he doesn’t care. His general vocation is to be some sort of a poet, whether that be some sort of rave poet, vocaliser, behavioural poet or written one who is occasionally supported by work and that has never diminished.

Howard believes one of Philip’s striking qualities is his lack of fear.

He is not scared; he is never timid. But he knows about fears and stands firmly and loudly against them. His father was fearsome. I don’t think Philip wanted to personally reject his father, but the man did a pretty good job of creating reasons to be rejected. To all this you add his talent, which he can’t escape, and which is driven in a way that seems not to seek at least certain types of reward. He knows his power, but he is not going to use it for power’s sake.

If anyone were in any doubt about Philip White’s protection racket, that is, protecting his own ferocious independence, they need look no further. Here he is, on ABC Radio National, 10 June 2011: ‘I’m not here to be popular.’ Hence the willingness to chew the hand that fed him. Railing against a vine-pull scheme that threatened the very fabric of small winemakers, at risk of being swallowed by corporations. Exposing winemakers who were altering their wines in underhanded ways. Pushing for a tax that is fairer to the producers of healthy wines than the cheap cask brigade. And there is always the main attraction: Philip’s unique style. ‘Sod the wine, I want to suck on the writing,’ says D.B.C. Pierre, winner of the Booker and Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse prizes and author of the bestselling novel Vernon God Little. ‘Probably takes a drink or two to connect like that; he literally paints his senses on the page.’

Philip and jeweller Albert Bensimon celebrating the legendary Saturday Table lunches (usually held weekly at T-Chow) at a party at the home of Paul and Vicki Nisenblat in the Adelaide Hills.

Philip White also has news for ordinary wine drinkers. He named Butterfly Ridge Riesling in a list of Top 100 wines. It was cheap – $10 a bottle. And now it’s not. He introduced readers to Hill of Grace Shiraz when it was $30. Now it’s nudging a thousand bucks.

Albert Bensimon says:

I read that having a good nose is actually having a good memory. It doesn’t matter if you know what it smells like, if you don’t have a good memory you don’t know the individual components. His memory is so good he can remember smelling a saddle thirty-five years ago. And he says, ‘That smells like horse saddle.’ Wine is the main target. But that nose gives its owner insights limited to a tiny percentage of the population.

Not everyone is a fan of Philip or his work. But there are many happy to place him on a pedestal. If wine writing were a planet, it would be barely visible in the night sky. Tiny. Yet influential, with the moon’s ability to pull tides towards one wine trend or another.

Nick Ryan, now with the Australian, was thrown out of university but ‘used the knowledge from raiding the old man’s cellar’ to land a job with a wine merchant before moving on to find ‘writing was easier than lifting’. Ryan maintains there are two types of wine writer. One is technically very able and reliable but on the pedestrian side: ‘Halliday writes like the lawyer he is.’ The other breed of scribe, Ryan says, is the equivalent of Neville Cardus on cricket, or Lester Bangs on rock music. They transcend the topic with their allusions, range and style. And an impure lust for the subject. Which brings Ryan to the one he believes tops them all: Philip White. He has been a fan since he was a kid who could only gaze at alcohol from a distance.

I fell in love with Philip’s work before I fell in love with wine. I used to read Philip’s tasting notes. They were amazing. Not being a wine drinker at that stage I couldn’t quite imagine a liquid in a glass could hold as much as Philip could find in there. You’d read and think: This stuff must be amazing; all this stuff going on in one glass of wine. Australian wine doesn’t know how lucky it’s been to have Philip chart its progress. If you look at wine writing around the world, there’s nothing like Philip. When we get together the last thing I want to talk about is wine, because he’s got such a wide-ranging, curious mind.

Sometimes I think his nose is a blessing and a curse, where his tasting notes are so packed full of ideas. And in newspaper columns especially, it’s more about getting quickly to the cheapest wine.

Bensimon believes Philip could have made a fortune from his skills. But he has – willfully – hobbled along the already rocky, potholed road of the humble freelancer.

He should be a very wealthy man. I’ve never known him to have the money he deserves. Anyone who is so eloquent and can write so well and have such knowledge of wine. He can write label notes like no one can.

Max Allen is drinks columnist for the Australian Financial Review. He came across Philip White in the mid-nineties and follows him still on drinkster.blogspot.com, which has been running online since 2008. ‘Philip’s writing, when he is on form, is staggering,’ Max says.

It leaves the rest of us for dead. I honestly read the stuff in drinkster.com more than I do any other Australian wine writer. Nobody writes like that, in the same way no one writes like Tim Winton. I can’t see the craft. I can’t see the thinking behind that sentence, it’s working on an emotional level. Philip is the same. And he has stuck to his independent, cranky guns, so it doesn’t matter about money. He’s been an enormous success.

Max makes a comparison with Gerald Murnane, the loudly lauded but enigmatic Australian novelist.

Hammering away at his novels out in the bush for years. Blithely uninterested in money or commercial success or awards. Yet a lot of people think he’s the greatest novelist of our generation. If it doesn’t matter to you, then you’ve succeeded.

But Max also recognises the dark side. It lit up around 2012, when natural/alternative wines were on the rise, championed by a newcomer, though hardly a youngster called Sam Hughes from Sydney. Exhibited the same affinity with language that Philip did. Crazy artist.

‘The movement really got under Philip’s skin,’ says Allen.

He got rattled, partly because he didn’t like the wines – finding them to be sloppy or sub-standard. There was this revolution going on under his nose that he didn’t quite get. Or that he got bitter and angry about. He took it out on me for a while. I think the new wave was an extraordinary jab in the arm of the Australian wine industry. Internationally, it had an impact way beyond its actual size.

The tensions bubbled and sizzled at an event in McLaren Vale organised by Amanda Pritchard, creator/director of the Adelaide Food and Wine Festival. Max now reckons Philip was under a misguided impression about the reason for the dinner, where he had been asked to speak. He thought it was to honour renowned Adelaide restaurant critic Howard Twelftree (aka the late John McGrath), who wrote for the Adelaide Review, and who Philip worshipped. But Max Allen spoke enthusiastically at the dinner about the new wave of natural wines.

So there was Philip, in a funk, getting more and more drunk and fuming. He gets up and makes this wonderful, articulate, impassioned speech about Howard. Then, a couple of days later, he has a go at me in a column in drinkster.com, really unnecessarily. Playing the man and not the ball. He was angry. There was some politics involved, I don’t know what the story was. But he wasn’t doing himself any favours; coming across as a dinosaur. Yet everyone knows he’s got some of the most progressive attitudes. He was out of touch with the movement, though he would argue that he wasn’t.

So there was Philip, in a funk, getting more and more drunk and fuming. He gets up and makes this wonderful, articulate, impassioned speech about Howard. Then, a couple of days later, he has a go at me in a column in drinkster.com, really unnecessarily. Playing the man and not the ball. He was angry. There was some politics involved, I don’t know what the story was. But he wasn’t doing himself any favours; coming across as a dinosaur. Yet everyone knows he’s got some of the most progressive attitudes. He was out of touch with the movement, though he would argue that he wasn’t.

I’ve seen him write about other people in a similar way. For example, I don’t know what’s gone on between him and Brian Croser. It was interesting, it told me a lot about the man rather than the writer.

There are public grudges. Also blind spots. I would argue his devotion to Penfolds dates back to Max Schubert. But we’ve all got favourites and it’s almost impossible not to. Philip doesn’t hide that.

————

Blood on the Typewriter: The World of Philip White is published by Wakefield Press.

Philip White was InDaily’s wine writer for more than a decade. You can read some of his work here.