Festival review: A Child of Our Time

As one of 20th-century music’s great anti-war statements, is the message of peace and understanding in Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time as relevant today as it was during World War II?

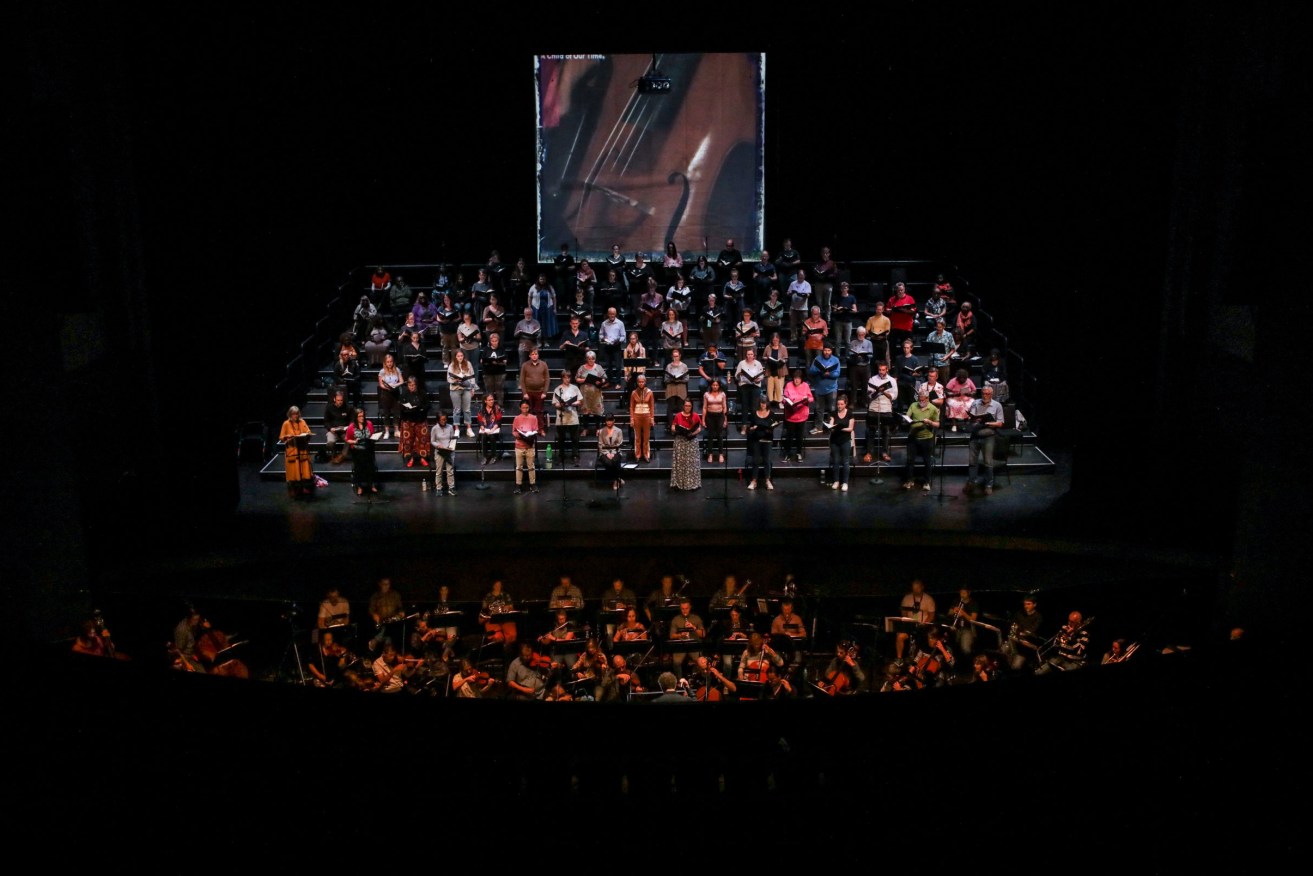

A Child of Our Time was performed by the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra and the Adelaide Festival Community Chorus. Photo: Tim Standing

He was a teenage malcontent who sought revenge against the way Jewish refugees were being treated in Europe in the 1930s, but Herschel Grynszpan could well have been a child of our time. His protest against the Nazis’ treatment of Jewish refugees, which triggered the bloody tragedy of the “Crystal Night” pogrom of November 1938, continues to reverberate around the globe for those who are persecuted for their race, colour, religion or politics.

Looking to make his own anti-war statement, Michael Tippett took up Grynszpan’s story in 1942 and created a mighty secular oratorio modelled on the choral works of Bach and Handel. In it, he wanted to issue a plea for peace and understanding at a time when the world, in the throes of war, was only just realising the scale of Nazi atrocities being committed against the Jews.

He called his new work A Child of Our Time in direct reference to Grynszpan, who shot a German diplomat in Paris while his Polish family were stranded in Germany and carried a postcard in his pocket reading “May God forgive me … I must protest so that the whole world hears my protest, and that I will do”. The title itself, though, is actually borrowed from a book by the anti-fascist writer Ödön von Horváth, Ein Kind unserer Zeit (1938), which tells of soldier’s struggles in a dictatorship between two wars.

So there is a lot to carry in one’s head when approaching this work. The immediate question for the present-day listener, though, is how Tippett’s great wartime oratorio might still hold power and significance these 79 years later, in a world that as we know is beset by conflicts, suffering and injustices of multiple kinds.

As this giant score slowly took shape, and the atmosphere inside the Festival Theatre fell into an awed silence, the answers became obvious. While using fairly conservative musical materials, A Child of Our Time gathers up a strong collective voice that seems to speak across the decades to all humanity.

Out rolled a performance of truly transfixing intensity. Leading massive forces, Sydney conductor Brett Weymark gave lift to the choir’s exultant tones and the orchestra’s lofty lines. Every word conveyed meaning, and not a note was rushed.

Members of the 85-strong Adelaide Festival Community Chorus. Photo: Tim Standing

Carrying the most important solo role, soprano Jessica Dean was simply outstanding. When the music took a questioning turn in her first song, “How can I cherish my man in such days, or become a mother in a world of destruction?”, a wave of vulnerability suddenly brought home the work’s full meaning. Dean, who has recently returned to Adelaide after many years in Sydney, has a voice of such expressiveness and beauty that one could not stop admiring her.

Tenor Henry Choo was similarly superb. In his solo “I have no money for my bread”, he generated true fervour and was powerfully communicative. Alto Elizabeth Campbell was excellent in her diction and Pelham Andrews supplied worthy bass solos.

Eighty-five singers made up the Adelaide Festival Community Chorus for this performance, and notably they included the Iwiri Choir singers who have connections to the APY Lands; this itself resonated deeply as a gesture towards reconciliation. All these assembled singers plus the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra were tremendously committed and well drilled under Weymark’s direction.

Brett Weymark conducts the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra. Photo: Tim Standing

A most distinctive feature in A Child of Our Time is Tippett’s use of African-American spirituals. These serve as places of shared meditation, rather like the chorales in Bach’s “St Matthew Passion”, and their rapturous treatment was a particular highpoint in this splendid performance.

All the performers donned ordinary clothes for the occasion, and to have the choir looking directly across to the audience made it feel as though barriers were being removed. It felt communal – an experience of genuine sharing for all who were gathered.

Forcefully reminding us of the work’s political genesis, a portrait of the sullen-faced Grynszpan was projected on a screen to the rear of the stage; and further stills and movie footage appeared as the work unfolded. Among them were photographs of refugee children peering through fencing, views of deforested land and the Earth from space, scenes of protesters waving “Black lives matter” placards, and numerous pictures of war-torn Europe.

Ultimately, A Child of Our Time is a symbolic work, and one wondered at times if these images were adding too much literalism. Tippett did write an accompanying note for the first performance explaining that the events relating to Grynszpan “are transmuted into the general” so as to express “fundamental patterns of human experience”. Even so, this was a powerfully effective performance, and one welcomed its creativity.

It is to be counted as one of the Adelaide Festival’s major landmarks.

A Child of Our Time was presented at the Festival Theatre for one night only as part of the 2021 Adelaide Festival.

Read more Adelaide Festival stories and reviews here.