SA miner’s Pacific plans ‘on hold’ as islanders fight back

A decision to let an Adelaide mining firm explore a small Pacific island devastated by phosphate mining has been suspended after a backlash from displaced former residents.

Centrex last month announced that it has signed an agreement to explore the feasibility of phosphate mining on Banaba, a six-square-kilometre coral island 298km east of Nauru.

Centrex hoped to explore the island via satellite remote sensing to determine areas of high phosphate concentration, saying it would take a “modern” approach to mining and rehabilitate the land in the process.

“Our objective is to demonstrate that significant remnant phosphate remains on Banaba that can be economically mined to satisfy increasing global demand for high-grade phosphate and at the same time, potentially fund the rehabilitation of the island,” the company said last month.

Banaba was ravaged by phosphate mining throughout the last century, leading to its residents leaving for northern Fiji.

But the administrator of the Rabi Council of Leaders – the governing body of the Banaban people who now live on the Fijian island of Rabi – posted on Facebook last week that the traditional owners’ opposition to the Centrex plan had led him to put the agreement he had signed “on hold”.

The move prompted a petition signed by 624 people, demanding that no mining occur and that the exploration decision be challenged.

The British Phosphate Corporation – a mining company controlled by Australian, New Zealand and British interests – ran the mine from 1900 until 1979. Some 21 megatonnes of phosphate was mined during that period, with records showing that “practically the whole island” was covered with a deposit of phosphate.

The nearly 80 years of mining activity has left the island looking like a “wasteland” according to Australian Association for Pacific Studies vice president Katerina Teaiwa, who is Banaban.

“It’s like what happens after a zombie apocalypse,” Teaiwa told InDaily.

“It’s quite a stark change.”

She said that the response to Centrex’s exploration plans was natural, considering many generations of Banabans had suffered through the years of phosphate mining and displacement.

“Any discussions of re-mining are quite triggering, because what you have now is multiple generations of trauma from displacement from villages and people being moved around on the island and bits of land being dynamited and blasted,” said Teaiwa, an Australian National University Professor at the College of Asia and the Pacific who wrote a book about the mining activities called Consuming Ocean Island.

Though Centrex has accepted the administrator’s decision to suspend exploration, managing director Robert Mencel told InDaily that the company was “hopeful that the opportunity in Banaba may eventually materialise”.

“Centrex takes all guidance from the Rabi Council of Leaders, the Banaban’s authorised representative and we will continue to work with them in a cooperative manner,” he said.

“It’s important to note that Centrex’s application to the Rabi Council of Leaders was for exploration activity and not mining activity.

“If mining does eventuate it could be years from now and so there is a long road to go down before mining might take place, if at all.”

He said that Centrex “followed due process at all times” in its discussions with the Rabi Council of Leaders administrator.

“There is only one process to follow and it wasn’t for Centrex to question or bypass this process,” he said.

“As a contemporary resources company it operates within the bounds of the law and respects authority and culture.”

Banaba mining

The story of Banaba and its population is “tragic” according to Teaiwa.

When the miners originally landed on the island, Teaiwa said the traditional owners were immediately displaced to make way for workers to “start digging up from under their houses”.

“They laid down the tracks, they built all the warehouses – an industry went up overnight. It went from ‘here’s some rocks’ to ‘now we’ve got a whole industry’, and there’s ships packed around the island too,” she said.

“So overnight Banaba becomes a hub in the Central Pacific because it’s that important. Meanwhile, nobody had barely come by it for the previous million centuries before.”

Banabans were eventually resettled at Rabi after World War Two.

“They replicated their villages on the new island of Rabi in the northern part of Fiji, but that’s not a landscape they’re familiar with,” Teaiwa said.

“They also don’t know much about indigenous Fijians who are living all around Rabi themselves and have certain protocols and certain expectations.

“This is a new population that’s just been dropped off – a new culture, a different language, different everything. So that causes lots of complexities and challenges over the years.”

The Banabans on Rabi were initially governed by a British colonial administrator, but that role was eventually removed in favour of a Rabi Council of Leaders made up of elected representatives and an elected chairman. Importantly, the Council is in charge of funds distributed to Banabans either from ongoing mining until the late-70s or trust funds set up to repay the islanders for phosphate royalties.

The Council is now run by one unelected man – the administrator Iakoba Jacob Karutake – who signed the Centrex deal.

Photo via Change.org.

As of 1979, mining of Banaba ceased, but Teaiwa said the miners just “packed up and left”.

“They left everything on the island – there was no clean up,” she said.

“Lots of machinery just rusted, broken glass, broken buildings, broken toilets and no good source of fresh drinking water because the mining damaged the freshwater collection under the ground.

“People returned to the island and people have been there as caretakers on the island since the 60s and the 70s, but they need certain kinds of supplies delivered regularly.”

‘Rehabilitation’

Banabans want their island rehabilitated.

Centrex said it that if mining proceeded it would also rehabilitate the land by filling in holes and cleaning up.

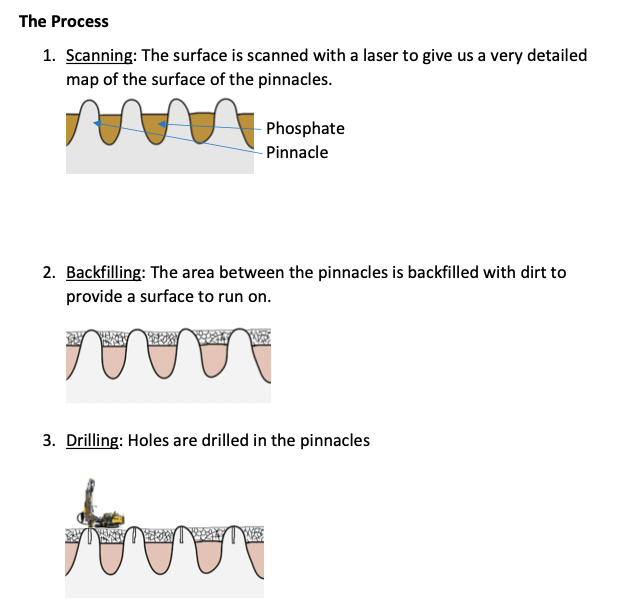

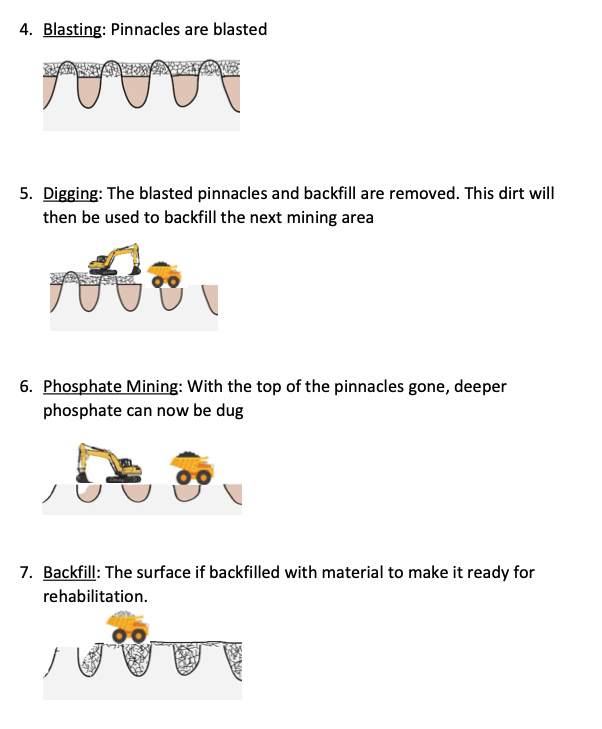

In documents obtained by InDaily, Centrex explained that it has managed the process with previous operations on Nauru.

Centrex managing director Mencel said the mining and rehabilitation plan was a “win/win” scenario.

“There has been no mining activity on Banaba for the best part of 50 years and likewise, very little reparation either,” he said.

“Much of the island has been left as a landscape of dolomite pinnacles that for 50 years, Banabans have not been able to live on or use productively in any way.”

Teaiwa said that while rehabilitation was a focus, “the goal here is mining”.

“It’s really not fair to a people who’ve been trying to figure out how to clean up that island and make it liveable and not a pile of rubble,” she said.

“You don’t have to re-mine anything to rehabilitate it.”

Speaking to InDaily, Toanuea Taratai, the chairman of Tabwewa – the administrative centre of Rabi – said mining was “not the wish of the people”.

“Our island has been devastated so much by mining,” he said.

“We want rehabilitation rather than mining.”