The doomed friendship of Rupert Murdoch and his first editor

Rupert Murdoch’s early years in Adelaide were marked by an unlikely progressive streak stoked by his friendship with crusading editor Rohan Rivett. Neither would last.

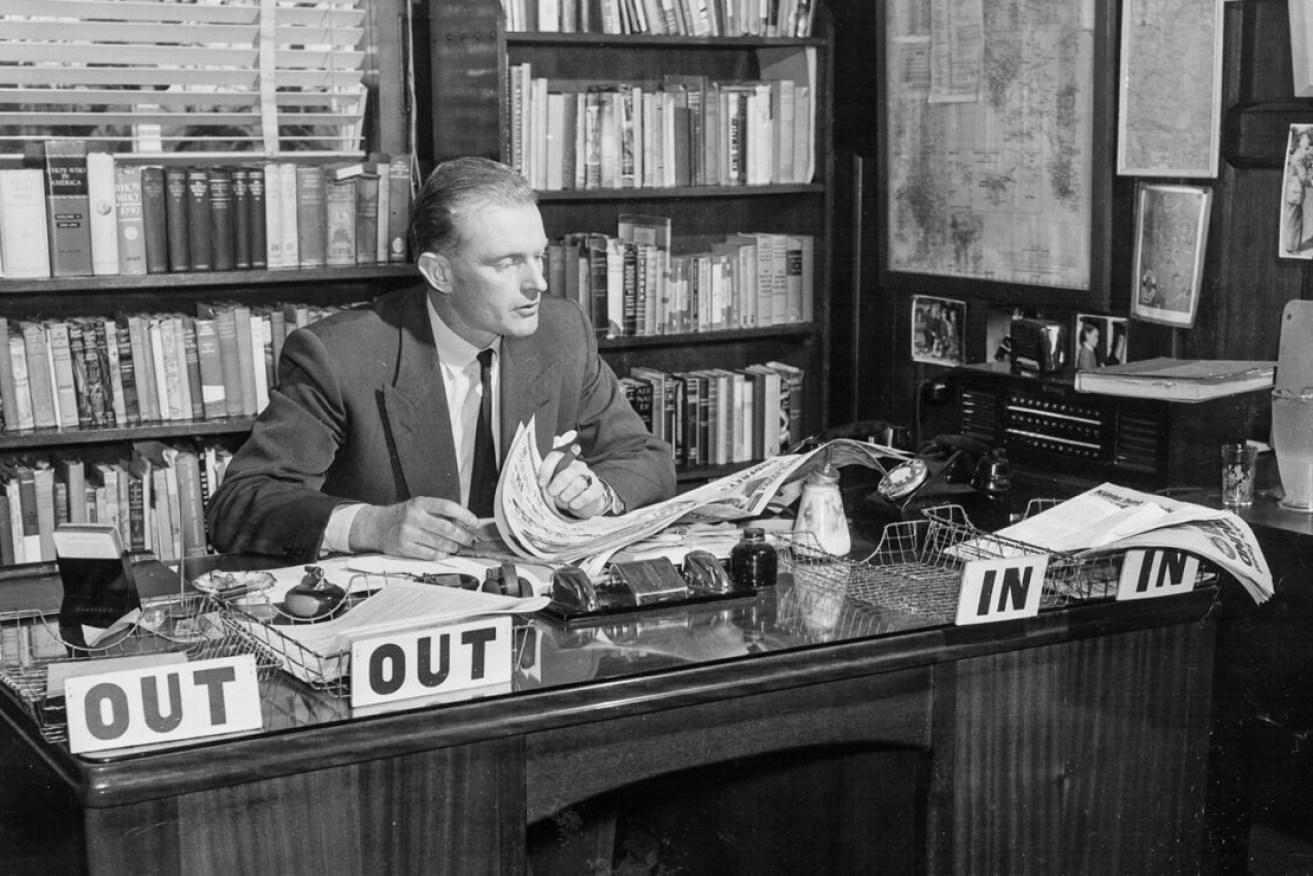

The News editor-in-chief Rohan Rivett in his North Terrace office, circa 1959-1960. Photo courtesy Rivett family

The following story by Walter Marsh is based on his new book, Young Rupert, published this month by Scribe Publications.

—————–

‘Ruperto, my old dear mate’: the doomed friendship of Rupert Murdoch and his first editor

Filed away in the archives of the National Library in Canberra is a decades-old letter that according to its author, a 29-year-old Rupert Murdoch, was the hardest letter he had ever had to write.

I first read that letter as I began to research the early history of News Limited and Rupert Murdoch a decade ago, when it soon became clear that two figures loomed large over the tycoon’s early rise. There was his father, Sir Keith, the early 20th century press lord who built up what was then one of Australia’s largest and most controversial media empires: the Herald and Weekly Times, often derisively referred to as the ‘Murdoch press’.

Then there was Rohan Rivett, a progressive, mercurial young editor installed by Sir Keith to overhaul the Adelaide News, the afternoon newspaper that Murdoch Sr was carefully positioning as an inheritance for his son. Although Sir Keith was the public face of the Melbourne-based Herald and Weekly Times, he never actually owned it, and spent his final years carving out a smaller, family-controlled chain stretching from Queensland to South Australia.

Rohan Rivett, Nancy Rivett and Rupert Murdoch on holiday in Salzburg in 1951. Photo courtesy Rivett family / National Library of Australia

But Rivett’s loyalties weren’t only to Sir Keith; the former Herald journalist had met the boss’s teenage son in the mid-1940s, and even visited him at the elite Geelong Grammar, where young Rupert was already building up a reputation for brash, loud but not entirely convincing radicalism (‘Comrade Murdoch’ and ‘Red Rupert’, some classmates called him). Rivett was well connected too, a grandson of Alfred Deakin and author of a bestselling account of his time as a prisoner of war in Burma. Clearly, Keith hoped Rivett would be a good influence on his son.

Rivett was posted to London by the time Rupert left Australia for Oxford, and Rivett’s young family became a sort of surrogate for the young Murdoch. The attic of the family home became ‘Rupert’s room’, while Rohan egged him on to pursue Labour politics at Oxford. Their correspondence in Rivett’s papers reveals a matey, almost fraternal friendship (“Ruperto, my old dear and occasionally drunken mate,” read one letter), hinting at a degree of youthful hijinks – gambling and drinking – that didn’t make it into the gushing reports Rivett sent to a troubled Sir Keith back in Australia.

In 1951, Rivett’s critical place in the Murdoch story was cemented when he was sent by Sir Keith to Adelaide to shake up a stagnating afternoon paper. Rivett soon named his second son Keith, with Rupert as godfather, but as editor of The News, he grew frustrated by his boss’s reticence to upset the dominance of the Herald and Weekly-aligned Advertiser. The News and its publisher News Limited had, until just a few years earlier, also been affiliated with the Herald, and Sir Keith had to maintain a delicate balancing act after convincing the board to sell its News Limited stake to Murdoch’s family trust.

Nevertheless Rivett got to work modernising the paper, boosting its circulation while needling parochial, conservative Adelaide’s sensibilities. Rivett tried to give The News a worldly, progressive tone – one curious memo sees him order the removal of unnecessary references to ‘New Australians’ from the paper’s court reporting to ease stigma against post-war migrants (“Anything that fosters the present prejudice can only be damaging,” Rivett wrote).

Newspaper House, corner of North Terrace and Victoria Street, in 1954. Photo: SLSA B-13011

When Sir Keith died, both men were thrown into a bitter power struggle, as Murdoch’s former colleagues, who had barely tolerated his attempts to cannibalise the Herald empire for his family’s benefit, now sought to seize it back. This is how, in 1953, 70 years ago, both Rupert and Rohan wound up in Adelaide, a pair of young, progressive interlopers in a small city where power, capital and influence were all tied up with The News’ rival, The Advertiser.

They came out swinging. In private, the pair railed against their “cunning old bastard” opponents, and a “reactionary clique” running “whisper campaigns” from the Adelaide Club. In the paper, they did the unthinkable and printed a front page story accusing The Advertiser of a ‘bid for press monopoly’ by trying to pressure Rupert’s mother into selling out.

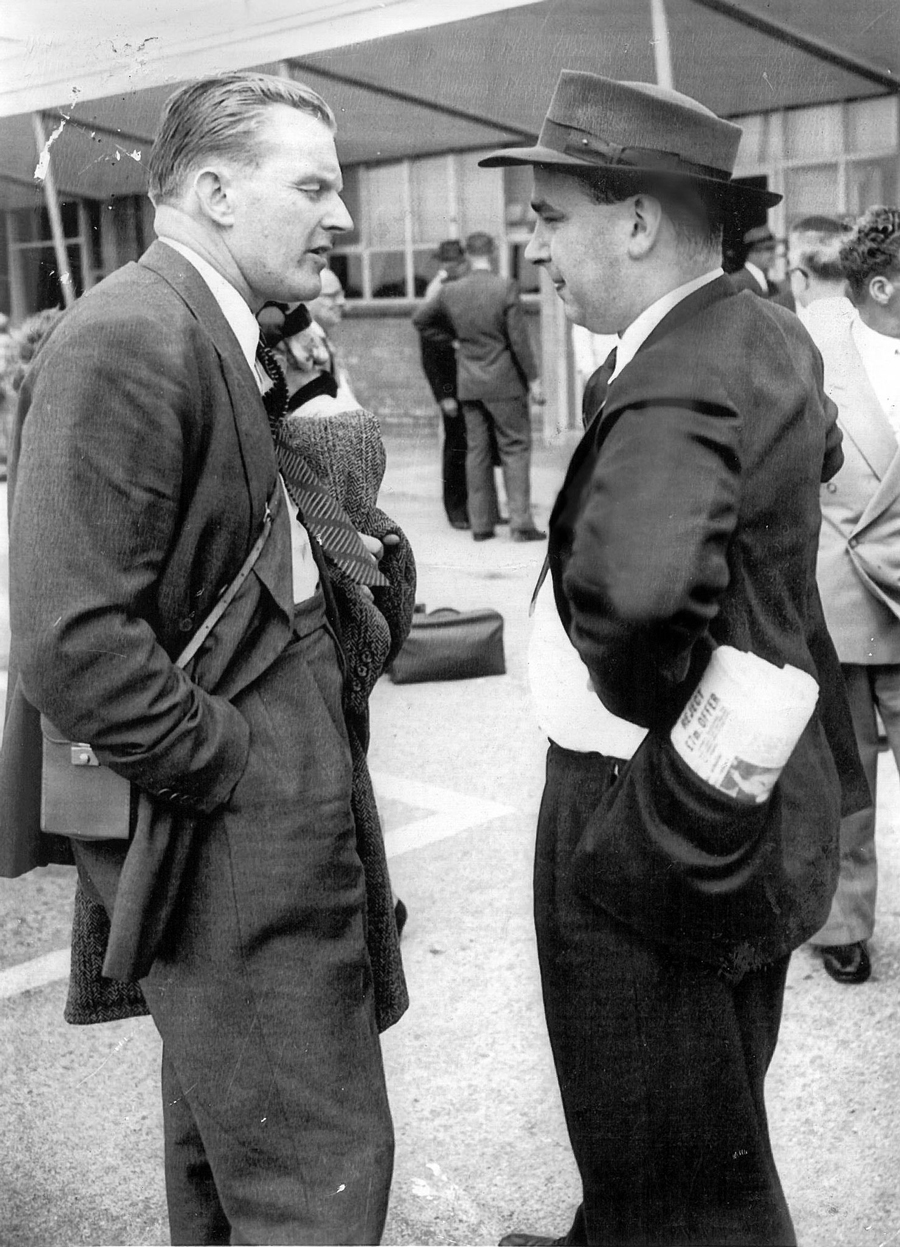

Rohan Rivett and Rupert Murdoch outside Adelaide Airport in 1955. Photo courtesy Rivett family

It was the first volley in a seven year campaign of boat-rocking, fierce competition and occasional scandal that culminated in Rivett and News Limited’s 1960 trial for seditious libel following their coverage of the Stuart Royal Commission. In 1959, Arrernte man Rupert Max Stuart was sentenced to death for the murder of a white nine-year-old, Mary Olive Hattam, near Ceduna. But the conviction rested on a signed confession of dubious authenticity, and under Rivett the paper had taken up the cause of a potential miscarriage of justice. It would be one challenge too far, landing both Rivett and Murdoch in court.

The week-long trial saw the processes and power structures of early News Limited forensically examined, culminating in Rivett’s witness box revelation of just who drafted the inflammatory headlines that had brought the scorn of South Australia’s establishment upon the paper: its young publisher, Rupert Murdoch.

But a few weeks after the final charge was dropped, Rivett was abruptly sacked via that short letter now housed in the National Library of Australia. Bewildered staff and Murdoch’s surviving relatives could only speculate how this most formative friendship could implode so spectacularly, and for years after his sacking Rivett hinted that he may yet write about his experience.

One day in 2022, also in the National Library, I finally found it: an unpublished, typewritten manuscript completed some time before Rivett’s death in 1977 of heart failure. It’s a pulpy novel about an afternoon newspaper whose editor faces a familiar-sounding libel trial, fictionalising real events so thinly that many scenes matched the official transcripts and eyewitness accounts I had read, almost to the letter.

But there is one private exchange that only one man alive can corroborate, that takes place between the editor and young publisher at the heart of the story, shortly before the former is fired – by letter, of course.

The libel trial showed how Rupert had once supported Rivett’s progressive crusades – even rolling up his sleeves. But this conversation in the novel captures the moment when the balance irrevocably shifts, and its fictionalised heir’s boyhood appetite for picking fights with the conservative establishment gives way to the pursuit of money and power.

When it’s over, Rivett’s stand-in, an editor named Donald Dare, reflects: ‘We who don’t own newspapers, don’t even own many shares, must always remain essentially freelance mercenaries whose sword is up for sale to those who’ve inherited papers or chains from dad or grandpa or uncle George.’

For years afterwards Rupert would populate his growing empire with Rivett’s former colleagues, creating a loyal ‘Adelaide mafia’ spread around the world. But, like the many editors who would join Rivett on the scrap heap, it was clear that no one was unexpendable – even someone who was once like family.

This article is republished from InReview under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

InReview is an open access, non-profit arts and culture journalism project. Readers can support our work with a donation.

![]()