Memoirs of an ANZAC

Barrie receiving assistance after being wounded at the Gallipoli landing.

Written in the 1930s and kept in a cupboard for more than 80 years, Australian Imperial Force officer John Charles Barrie’s World War I memoirs give a first-hand account of life on the front.

Barrie enlisted in 1909 against his mother’s wishes, was wounded at Gallipoli, and then escaped from rehab in England to return to fight with the 8th Battalion in France.

His story – a matter-of-fact telling of his experiences and the horrors he witnessed – were brought out of storage by his granddaughter, Judy Osborne, and finally published last month by Scribe Publications with the title Memoirs of an ANZAC.

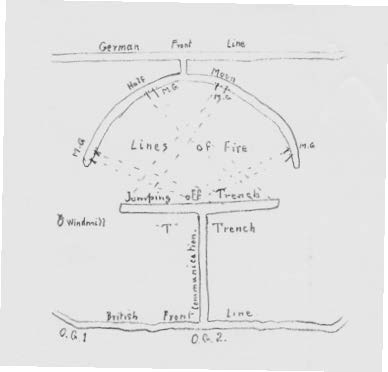

The following extract, from chapter 13, describes events that took place in France in 1916 the day after a party led by Barrie had dug at ‘T’ trench in No Man’s Land to pave the way for an attack on the Germans forces.

Next morning, an item of pleasant news came to the battalion. Owing to the heavy casualties sustained by the front-line battalions (5th and 6th), they were not strong enough to carry out the attack. The 7th and 8th would therefore relieve that night, and the attack would be carried out by the 8th Battalion. We were always lucky. However, ‘war’s war’, and we took it philosophically. What you lose on the roundabouts, you pick up on the swings.

We spent a quiet day resting, if one could call it quiet with the thunder of the guns in our ears nearly all day. Still, one gets used to that. I felt very worried about the job ahead of us that night, and though I could not help feeling glad that my company was not to take part in the actual attack, but would remain in support, having done its task the day before, I could not help feeling concerned about those who were going in. I felt pretty certain that the enemy would have a surprise prepared for us. However, I kept my mouth shut on the subject. I knew nothing. It was only suspicions, and it was no use worrying the officers concerned about a thing I was not sure of. They had enough on their minds already.

We moved in early in the evening. The attack was to take place at midnight. The result was as I anticipated. Let us pass it over as quickly as possible. It was too terrible to dwell on, or to describe in detail. The Germans had prepared their trap under cover of darkness, quietly and unobserved, and our poor fellows ran into it with terrible results. They had dug a half-moon trench around our ‘T’, and caught them in front and flanks with machine guns, in this manner shown here.

Poor chaps! They never had a chance. They took the punishment, alright. We lost nearly 300 men and, of course, did not reach the objective. It was the only defeat the 8th Battalion ever suffered, and they were in no way to blame for it. It had practically been arranged for them by higher authority on an open invitation. I have often thought since that the enemy allowed us to complete that job the day before in anticipation of a bigger prize. Much as I appreciated the good work of the staff, I think sometimes, through ignorance of the actual front-line conditions, that they carried stern discipline a trifle too far, as on this occasion.

The men of the 8th hated being defeated, but they were never ashamed of it, and had no reason to be. They behaved wonderfully. They were driven back to their trench, rallied, and tried again four times, led on each occasion by Captain Hardy. Hardy was a Duntroon graduate and one of the most popular officers in the battalion. He was suffering under the smart of an unjust accusation made against him by the CO. Being a regular soldier, he felt it more keenly than others of us might have done, and he laid himself out that night to win special recognition, and so force the CO to withdraw. The whole battalion knew of it, and was seething with indignation on account of it. They loved Hardy.

On the fourth attempt, he was badly wounded close to the German Line. Our attack was again repulsed, and the survivors driven back to our line. No further attempt was or could be made. Our losses were too severe.

But Captain Hardy had not returned. Someone said he was going to look for him. Others just went without mentioning it, in case it was forbidden. I never saw anything like it. Practically the whole garrison spent the rest of the night in No Man’s Land searching for Hardy. They brought in numbers of their wounded mates. Handing them over the parapets, each would enquire if Captain Hardy had been found. On being told no, they simply wriggled away and continued the search.

After a couple of hours, one of the officers, Lieut. Goodwin, came across a badly wounded man in a shell hole who had seen Hardy. He had crawled into the same hole, badly hurt. Being unable to assist him, Hardy had given the man his water bottle, expressed his intention of trying to crawl back to our lines, and promised if possible to send him assistance. He showed Goodwin the way Hardy had gone. That was just like Hardy to give away his water bottle, the thing he needed most at the moment, to a wounded comrade. Goodwin got the man in and went back for Hardy, but although the search continued until nearly daylight, no further trace of him was found. The affair cast a gloom over the battalion for days. I never knew the men to take anything to heart so much as the death of Captain Hardy.

Men cried that night. Their defeat and the loss of so many comrades was bad enough, but they all felt, and in some cases openly declared, that Captain Hardy’s life had been sacrificed through an unjust charge laid against him by a man who was not fit to lick his boots. His name will never be forgotten by those who served with him.

Extract from Memoirs of an ANZAC – a first-hand account by an AIF officer in the First World War, by John Charles Barrie, $32.99. Republished with permission from Scribe Publications.