Duncan drowning files a disturbing reminder of past attitudes

Coronial files on the River Torrens drowning of gay university lecturer Dr George Duncan 50 years ago reveal that many swept up in the inquiries faced intrusive, intimidating police questions while others lost their jobs – collateral damage of an unsuccessful quest for justice.

A memorial to Dr George Duncan near the site of his death in the River Torrens. Photo: Adelaide Law School Facebook page

The River Torrens had barely closed over Dr Duncan’s head on the night of May 10, 1972, when reports began circulating that three vice squad officers were suspected of pushing him in.

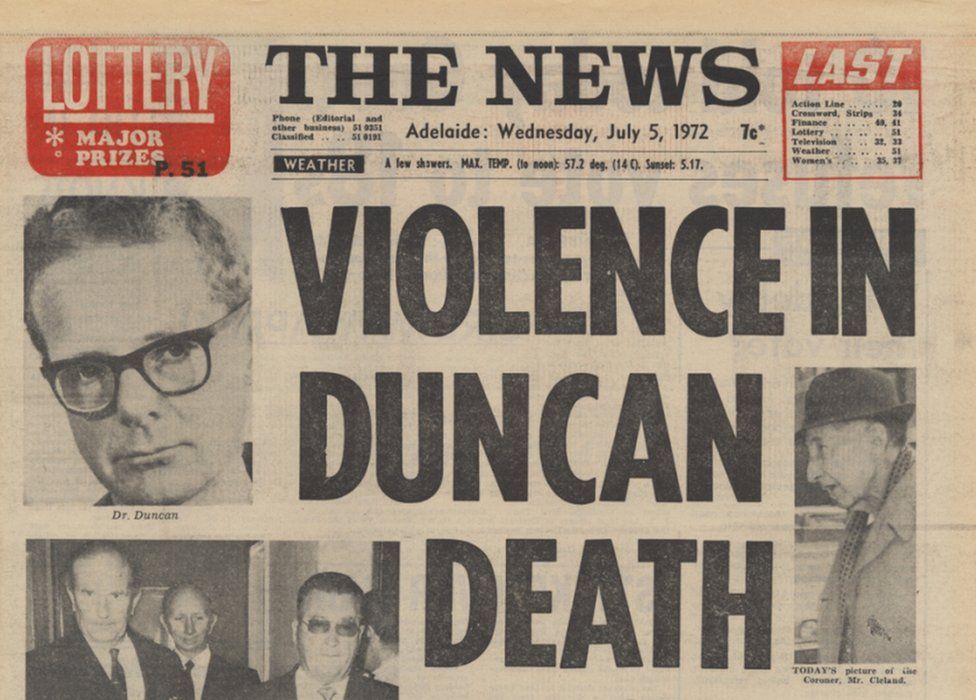

What unfolded next was a scandal of the highest order. The hitherto untarnished reputation of the state’s police force was drenched in muck, while public attention was transfixed upon daily headlines: “ Shock Evidence”, “Vice Squad Detective Suspended”, “Violence in Duncan Death,” etc.

All that was missing from the drama was a resolution: the eagerly anticipated, ‘who done it’. Despite the combined investigatory powers and might of the police force, the Coroner, and the courts, no one has ever been convicted over Duncan’s killing. That is not to say that justice, in the broadest sense, wasn’t done. The ‘architect’ of the violence, as opposed to the unidentified perpetrators, was swiftly hauled before parliament and ‘convicted’ for its pivotal role in Duncan’s death.

The culprit was the law itself. George Duncan, who lectured at the University of Adelaide Law School, was gay. The River Torrens was a well known meeting place for gay men seeking company and/or sex. On the night the academic ventured down the river banks, male homosexuality was illegal in all Australian states and territories. Never mind being caught in the act; the law effectively criminalised gay men because of who and what they were. And as the law leads, so attitudes and actions dutifully follow. The law made homosexuals the targets of violence.

The great legacy of Duncan’s death is that it shook SA into becoming the first Australian jurisdiction to successfully decriminalise homosexuality – a push down the path to becoming a more just society. But in the quest to achieve justice for Duncan the individual, other people and other lives became collateral damage. That process started with the Coronial inquest into the law lecturer’s death.

With police investigations seemingly stalled, and under significant pressure from the University as well as parliament itself, the Dunstan government ordered the Coroner to hold an inquest into Duncan’s drowning. It began in early June, 1972, concluding a month or so later, with Coroner Tom Cleland unable to identify Duncan’s assailants. Cleland wound up his findings with the words, the death was “due to violence on the part of person of whose identity there is no evidence”.

No one was happy. The police complained the inquest had stymied their efforts, suggesting without it they’d have been successful. Eventually. There were demands for a Royal Commission, notably from former Attorney-General Robin Millhouse. At the time, Premier Dunstan and his senior ministers largely kept their own counsel on how the coronial inquest had been conducted.

Now, with the 50th anniversary of Duncan’s death approaching, former Dunstan staffer Greg Crafter – later an MP and minister – has spoken of the anger being played out in private.

“Cleland had gone to sleep sitting during that hearing,” Crafter recalled.

“I remember Don [Dunstan] coming to me at the time of the Duncan inquest and being furious about Cleland. He was a very old man, clinging on to that role and exercising the authority he believed he had with little skill … I think that is the correct way to say it.”

Crafter’s insights come from unique place. Then aged 25, he had started working for Premier Dunstan in 1971. From there, Crafter was hired by Attorney-General Len King, to work with him – the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the two men. When Dunstan retired from politics in 1979, Crafter assumed his mantle as the member for Norwood.

“In terms of the witnesses in the Duncan inquest, he [Dunstan] was very concerned that they were not being given proper protection,” Crafter said.

“They were televised coming in and they basically lost their jobs and were persecuted. In fact Don asked me to help find jobs for a number of those people, and Don himself had spoken to Hardy’s [ wine company] so we got a number of the guys jobs there. We looked after those guys as best we could.”

One of the people to have lost his job through appearing at the inquest was a 33-year-old gay man employed by South Australian police to wash cars. He was at the Torrens on the night of Duncan’s death, and explained to the Coronial inquest what happened once his sexuality became known.

Q: Until last Friday you were employed by the police department as a car washer?

A: Yes

Q: You voluntarily resign from the police force on Thursday?

A: Yes.

Q: Why?

A: It embarrassed the police force and I didn’t want to embarrass them any more.

Police did indeed have much to be embarrassed about during the winter of 1972. A gay car-washer, though, wasn’t chief amongst them. The man told the court he had a grade three education. Perhaps, if there was any small justice, he was among those men Greg Crafter helped find another job.

The next step came out of the failure of the first. Within days of the Coronial inquest lurching to a question mark finish, a taskforce of 10 police officers was formed to take over the Duncan investigation. The new police commissioner, Harold Salisbury, had two Scotland Yard detectives flown out from London to lead inquiries. The move was broadly welcomed, including by homosexual law reform advocates.

The Adelaide chapter of national organisation, C.A.M.P ( Campaign Against Moral Persecution) wrote in their September, 1972 newsletter: “Two Scotland Yard detectives and the CIB are making extensive enquiries. They are visiting parties, and meeting homosexuals, and deserve all the help we can give them.”

When the Scotland Yard report was finally tabled under parliamentary privilege in the early 2000s, it showed the English detectives believed Hudson, Cawley and Clayton – the three vice squad officers suspected of throwing Duncan into the river – had done so.

What the report didn’t have was the evidence to support charges. Deftly ignoring the notion that crime solving was actually their job, the English detectives blamed the victim. Not George Duncan, but another man, Roger James, who’d been heaved into the water that night along with the law lecturer. Effectively, the detectives said if James had been a better witness they could have produced an outcome. That was outrageously unfair – persecuting a man who simply wasn’t sure who’d assaulted him, and declined to pretend otherwise.

Roger James has steadfastly refused to live life defined as ‘the other man thrown into the river’. Consequently, he rarely speaks about the events of May 10th 1972, and certainly does not do so publicly. In 2005, however, Roger James did give an interview to the ABC, during which he had a few things of his own to say about the Scotland Yard coppers.

“A pair of dodos,” he observed, pithily. “They were just here for a bushman’s picnic. I mean they were so anti-gay, they were rude, incompetent and they were just here to have a good time. They weren’t interested in anything.”

As James was being assaulted in 1972, his ankle became wedged in wooden pylons along the river bank. He heard the bone snap as he hit the water. Later in the ABC interview he was asked: ‘What if you hadn’t broken your ankle?’ Roger James thought about the question for a moment, before replying; “I can only say, in looking back, I’d have probably gotten out of the river and gone home and not said anything … I’d have saved myself a whole lot of shit.”

Unfortunately, for anyone caught up in the Duncan case, there was no avoiding the substance Roger James speaks of. He is far from alone in holding a less than flattering opinion of the Scotland Yard detectives and their report.

The English detectives believed Hudson, Cawley and Clayton – the three vice squad officers suspected of throwing Duncan into the river – had done so. What the report didn’t have was the evidence to support charges

It didn’t help that sometime after their retirement, the two detectives were convicted on charges of tax evasion and corruption. Together, it’s fuelled a view police didn’t really try to solve the Duncan case – an example of the blue brotherhood closing ranks.

There’s a blunt truth, I believe, we should keep in mind this anniversary: Dr Duncan had his day in court. In the mid 1980s, the former vice squad officers – Francis John Cawley, Michael Kenneth Clayton and Brian Edwin Hudson – were charged with Duncan’s manslaughter. Charges against Hudson were dismissed at committal hearings because of insufficient evidence. Cawley and Clayton faced trial and were acquitted, by jury, in 1988. As one of the state’s most distinguished legal figures has put it, “Duncan’s is a straightforward case in many ways. It hinges on identity, and no one could point in court and say, ‘I saw him throw the man in’.”

Sometimes, the justice system fails to secure a conviction. That’s not the same as the justice system failing. The Scotland Yard detectives may well have been a pair of picnicking dodos, but behind them and their report, South Australian police were doing a vast amount of work. In the space of a couple of months they’d re-interviewed witnesses who were at the Torrens when Duncan died. They also pushed their inquiries wider, speaking to people nowhere near the river, and often with the flimsiest of connections to the matter.

Those statements were not made public when the Scotland Yard report was released in July 2002. The Duncan statements land on a table in the Coroner’s conference room with a thud, producing that familiar odour of old paper as they do. There are almost 400 hundred of them, all contained in a couple of bureaucratic beige folders. If weight alone is a measure of intent, the folders are symbolic of a concerted effort to identify who was responsible for Dr Duncan’s death. The results of those efforts, though, are mixed.

The slightest lead was pursued. Even in 1972, Lucia’s cafe in the Central Market was as beloved of the city’s legal fraternity as it is today. Police heard that a woman, a courts employee, sat next to Duncan one lunchtime at the cafe. They interviewed her. She said, if indeed the encounter had happened, it was unintentional – she had no idea who Duncan was.

The restaurateur at the establishment where Duncan dined on his first night in Adelaide was spoken to – the academic was a good customer, who always ordered the best wine to share. That redoubtable old Adelaide institution The Pancake Kitchen got a guernsey too. A waiter told police about Duncan’s usual breakfast – pancakes, maple syrup, black coffee – and his preferred table. There are dozens of statements of a similar vein, so many in fact they could support an argument, if one was so minded, that investigators were clutching at straws. Maybe they were. Or maybe they were trying to do their job, while hoping something might turn up.

Duncan’s is a straightforward case in many ways. It hinges on identity, and no one could point in court and say, ‘I saw him throw the man in’

Like absolutely everyone else, I’ve wondered over the years: are there any famous, powerful names in the files? There are not. I expected some of the statements to be sad, full of either ignorance, or self loathing, or both. There’s plenty of that. What I didn’t expect to be doing was laughing out loud. In statement S188, a minister of religion recounts his meeting with a young woman, and another Duncan case witness in Hindley street, on the night the law lecturer drowned.

“I would be able to recognise this female again because she was out of proportion with her over large breast development”, the minister told police. Then he added, helpfully, “She had a nice personality.”

It’s not the case cracker police hoped for, but God’s servant on earth would surely have had fans of the “Carry On” films rejoicing. I see Kenneth Williams playing the priest, and, for obvious reasons, Barbara Windsor as the young woman.

Statement S188 is so distractingly bizarre, it takes a moment to notice the blue-coloured pencil used to underline the minister’s observations. That same blue pencil line is, in fact, used with exquisite neatness throughout the statements. After they were typed up, someone has gone through, highlighting matters deemed of particular relevance: things like car registrations and sexual preferences. Or, in the matter of S188, a priestly preoccupation with big bosoms.

The blue pencil was probably a standard procedure of the time. It makes cross referencing easier. But there is a striking irony in its use, too. Traditionally, the thin blue line serves as a metaphor for the fragility of civilisation – just a few police, in their blue uniforms, standing between order and chaos. For South Australians, the blue line also reaches back into our shared childhoods. In this well mannered city, a thin blue line painted on the streets is all that’s been needed to keep generations sitting quietly as the Christmas pageant goes by – police and citizens trusting one another to do the right thing. Duncan snapped the trust in that line, along with our view of ourselves.

On the face of it, some of the most significant interview statements contain allegations of police throwing people, besides Dr Duncan, into the river. Statement S384 was made by a 68 year old man, who said in 1970 he’d been thrown into the river by two unidentified officers who’d once arrested him on a gross indecency charge. It involved a 14 year old boy.

“Both chaps then grabbed hold of me, one under each arm and tossed me six or seven feet into the River Torrens,” S384 recounted. Police followed the man’s allegations up, speaking to a friend of S384. That person said he too had been told of the claim, but that it was made when S384 had been “drinking heavily”. At the top of S384’s statement, underlined in blue, are the words “half-caste Aboriginal”.

The statement made by S297 also alleges violence at the Torrens. Unlike S384, it does not claim the act was perpetrated by police. What’s significant about S297’s statement is its time frame.“ I went there [the Torrens] with ****, and he was thrown into the River Torrens by a blonde man in his early twenties,” S297 said. “This took place about 2 weeks before the death of Dr DUNCAN.” Blue pencil and capitals were broken out for that.

Police individually interviewed a group of self described “poofter bashers” who’d been arrested at the Torrens a month before Duncan’s death. They told the officers they’d gone to the river intent on “rolling a few poofters…this meant beating them up”. The evening’s planned entertainments veered off script, after an approach was made to the wrong man. “I said to this man, ‘Hello Darling’ ”, S229, told the interviewing officer. “After a brief conversation this man told me he was a detective.” Sadly, for history’s sake, there are no further details of what must have been a delightfully awkward exchange.

None of this, though, put police any closer to identifying Duncan’s assailants. These men weren’t witnesses to that event. Rather, the value of their allegations lies in the wider portrait they help paint of violence on the river banks.

A 2015 memorial service on the anniversary of Dr Duncan’s death near the university footbridge site where he drowned. Photo: Adelaide Law School Facebook page.

Given the wide nets being cast by police, and the fact tragedy has a habit of bringing out the worst in some people, a few character assassinations were inevitable. Interviewee S264A said of his partner, (no less), that “…he is the sort of person who will tell lies all the time. He likes to think he is more important than other people.”

There’s an instance of a young gay man being a self aggrandising gossip, which resulted in another individual – a teacher at a church school – losing his job. Even Dr Duncan himself wasn’t spared. When S362 was asked by police if he knew the University academic, he replied “I certainly have not been with him, because he looks dreary, miserable and is definitely not my type. ”

The police, too, sprinkled the statements with their observations of the people they hoped might help them solve the case. Of S180, the interviewing officer said the man possessed a “sweet sounding voice, [and] receding hair”. The sad retreat of another person’s hairline was also noted, along with their “protruding eyes”.

It was, however, Interviewee S262 who copped the cattiest assessment. The man had a “dark complexion, fat face, very fat,‘big SLOB’, dark hair. A butch homosexual,” the officer wrote of S262. As intended, the capitalised word, SLOB, slaps one across the face. But the use of the word,“butch”, is much more noteworthy. Butch is a relic of gay lingo from the 1970s, along with its complementary term, “bitch.” It refers to someone who prefers taking an active role during sex, which, ipso facto, explains bitch.

In the first paragraph or two of many statements, it’s noted whether the interviewee is “butch or “bitch”. The vital importance police attached to the fact is highlighted by the now ubiquitous blue pencil. The question was asked over and over, of many interviewees. That said, there’s a discernible age and class bias at work. The ‘butch or bitch’ query tended to be put to younger, less educated men (or boys, in a couple of cases), rather than better educated, older men.

It’s inconceivable a gay man back then would volunteer details of their sex lives to police. This is what the police taskforce itself was asking in its endeavours to identify who killed Dr Duncan. Overstating how profoundly frightening, confronting and intimidating that question would have been in 1972 is no easy task. Nevertheless, many did answer it, quietly asserting who and what they were.

“I am a homosexual. I am the ‘bitch’, in homosexual terminology,” S264 told the interviewing officer when asked. “I have been this way since I have known about sex. I have always like dressing-up and being like a girl. I have not got a ‘butch’ ”. The person who said that was a 15-year-old boy. Police noted that the lad “speaks nicely” and had a “pimply face”. I think it fair to say that this pimply boy was already a brave man. There are others, too. A 21 year old said, “I am a homosexual. I take the man’s part.” Another 21-year-old declared himself a “transvestite … that’s the medical term.”

Even if these men had been staring Duncan’s assailants in the face – which they weren’t – it’s hard to envisage how knowing what they did in bed might help secure a conviction. Obviously, police knew that. So why was the question asked? Part of the answer, I believe, comes back to the law – again. South Australia, along with all other state police forces in the 1970s, had a special branch. It saw its job as a quasi intelligence service, keeping tabs on communists, subversives, homosexuals and anyone else deemed a potential risk to state security, or public safety and morality.

Additionally, there was another separate set of files known as “the pink files”, kept on prominent gay South Australians. According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, the Chief Justice, John Bray, was the subject of one of them. The surveillance of gay men was seen as a core activity. Thanks to the law, it made perfect sense to the police in 1972 to use the Duncan investigation as a tool to gather as much information about as many people as possible.

It didn’t matter if it wasn’t relevant to the case at hand, or if it was incompatible with its primary purpose. It’s yet another example of the corrupting influence of the law as it stood at the time.

The surveillance of gay men was seen as a core activity

As noted earlier, there are no famous names in the files – just ordinary people swept up in extraordinary circumstances. But this is Adelaide, with its few degrees of separation. It follows there are familiar names.

Two stand out to me, both of them were family friends. I recognised S297’s name the moment I saw it. As I sat in the coroner’s conference room, reading S297’s statement, I couldn’t help but think of a dinner one night at his home in the 1980s. He asked us what we thought of a new painting he’d just bought – an abstract of the Sydney Granville train disaster. It makes no sense at all, but memory is an eccentric thing, inclined to its own agenda.

The question kept going around in my head: ‘If a train crash was suitable dinner conversation, why not the Duncan case?’ There are parallels, after all. We had no idea S297 had ever been interviewed about the Duncan case, or that he had a friend thrown in the river two weeks earlier. He’s been dead for years, so I can’t ask him why he never said a word. I guess I already know the answer.

After he’d left the police force, Francis John Cawley went to work for a stock supply firm. My parents, who bred racehorses, had known Cawley well before the Duncan scandal. Like many other people, my mum and dad enjoyed Cawley’s company a great deal. Now, in his new line of work, they saw the former police officer more often, or so it seemed to me. Times were changing but in country South Australia some notions of the Victorian era were enjoying their last gasp, especially the one that children are to be seen and not heard. When Cawley breezed in, he made my sister and me feel like he wanted to both see us and hear us. His arrival at our place was always greeted with excited shouts, “Mr Cawley is here! Mr Cawley is here!” I don’t know if Mr Cawley remembers me, an attention craving kid. I have only good memories of him, from that innocent period, frozen in time when I was 10. That would have been the last time I saw him.

These little reminiscences are nothing of great note, and yet they also mean everything. A part of my childhood and youth, neither Cawley, nor S297 were in my life through any choices I’d made. And yet that’s the very reason why their memories are everything.

So much of who we are is fashioned from decisions and choices others have made. Late one night, half a century ago, a small group of people made their choices on the banks of the River Torrens. One man’s life ended, and everyone else present had theirs changed forever. But the ripples kept moving out, in ever increasing circles. Eventually they lapped up against us all, helping to make us who we are today.

As a matter of fairness and at the Coroner’s request, individual names were not used in this article. Simon Royal would like to thank Coroner David Whittle and court manager Michele Bayley-Jones for their generous assistance.