Richardson: Advisers advise, but who’s making the decisions?

It’s becoming a well-worn refrain in South Australia that it’s much harder to lift coronavirus restrictions than impose them. Which, writes Tom Richardson, might explain why we’re doing a much worse job of it.

Police watch on at last weekend's Black Lives Matter rally in Adelaide. Photo: Morgan Sette / AAP

Early this week, our de facto Premier Grant Stevens announced that a crowd of roughly 2240 football supporters would be allowed into Adelaide Oval for tomorrow night’s Showdown – a decision, he noted, “taken on the back of the fact that we had a significant number of people in Victoria Square on the weekend for a protest activity, and that was conducted in a relatively safe manner”.

In other words, the rationale underpinning our current coronavirus pandemic response is not dictated by a government agency, an appointed mandarin, and certainly not any elected official.

It’s dictated, apparently, by the organisers of last week’s protest.

Protesters in Adelaide last week. Photo: Morgan Sette / AAP

It was incredibly conflicting watching the thousands converge on Victoria Square last week.

On the one hand, the protest was a powerful local expression of an international movement, an important distillation of the brutal reality that this movement is much more than a stand against institutionalised racism in the US.

Protesters cited the rate of Aboriginal deaths in custody, itself an expression of high incarceration rates, in turn an expression of embedded disadvantage.

On the day of the protests, West Australian corrections confirmed that a 40-year-old Aboriginal man had died in custody at Acacia prison, near Perth.

And yet the very articulation of Black Lives Matter rings uneasily against the very real possibility that these protests could cost lives.

In Melbourne yesterday, a protester from that city’s weekend rally tested positive for COVID-19.

They were asymptomatic at the time of the event, but could have spread the virus. We won’t know if they did for some days yet.

The chance of that happening in a state such as Victoria was always high, hence their government discouraged people attending.

The risk seemed less in SA, where authorities allowed the rally to go ahead – a decision that prompted a different kind of outbreak. A “what about me” outbreak.

In the case of “why can’t I attend the footy?”, it’s a trite and shallow response.

In the case of “why can’t I attend my friend or family member’s funeral” though, it’s understandable.

Protests are important: they bring people together in a shared outpouring of emotion.

But so too are funerals.

Such sensitivities called for a particularly nuanced form of leadership.

Instead, we got the Police Commissioner penning an editorial in a local paper justifying why he let the rally go ahead.

Which, putting aside the inherent irony of a protest that is effectively anti-police having to be given a polite “all clear” from the state’s top cop, was a compelling enough argument: that it was better to work co-operatively with protesters than outlaw them.

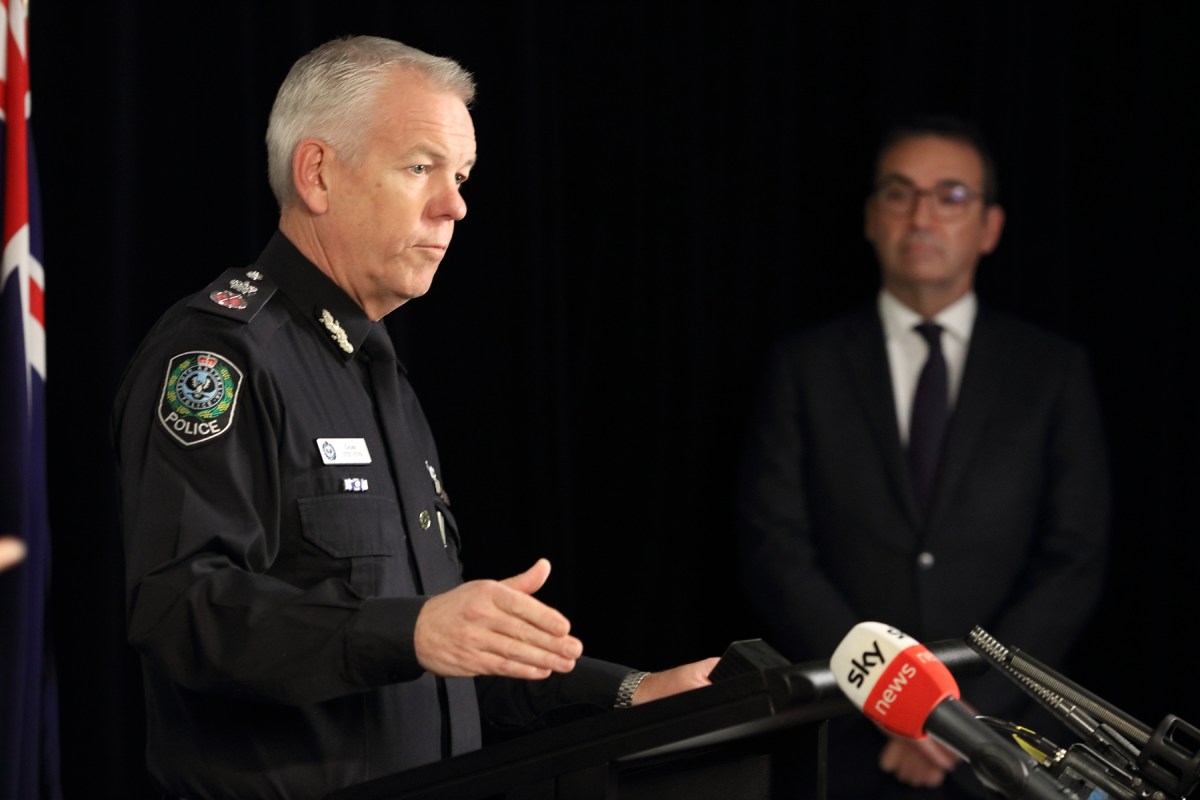

Grant Stevens, as the state’s emergency co-ordinator, has taken centre stage over Steven Marshall. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

But a national media preview of the Black Lives Matter protests emphasised a telling distinction.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews, we were told, urged protesters to remain at home, warning the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic meant it “would not be safe… to be having gatherings of that size”.

By contrast, NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian initially noted she would never want to “take away the right of people to… protest” before changing her tune entirely when the number of prospective attendees escalated dramatically.

As for SA’s own Steven Marshall? His office referred the media’s inquiries to police.

It’s a telling response from a political leader who appears increasingly incapable of having an opinion that isn’t first approved by his senior bureaucrats and advisers.

In recent media rounds – including with an Adelaide primary school’s in-house podcast – Marshall has made the point that he is an early riser, and during the coronavirus crisis has been routinely getting up around 4am to get a heap of work done before the “official” workday begins.

It’s hard to imagine what he manages to achieve though, unless Stevens, chief public health officer Nicola Spurrier or one of the Premier’s key media advisers also happens to be up at 4am.

We can’t complain, of course.

That recent snafu over a missed email that saw a woman who’d been granted a compassionate exemption to SA turn up unannounced before subsequently testing positive to COVID-19 notwithstanding, we currently – again – have no active cases in SA, which speaks for itself about the success of the state’s authorities.

In per capita terms, however, our achievements are given more context – with SA’s 440 cases this month ranking equal third-highest (with Victoria and the ACT) per 100,000 of population, behind Tasmania and New South Wales.

I recently suggested that the Marshall Government’s bent for deflecting responsibility for key decisions onto its so-called Transition Committee was becoming problematic, but those problems have since become starker.

To his credit, Marshall has been front and centre in the public eye throughout this crisis, but while he’s strong on rhetoric, he’s frequently short on detail.

Hence, it took days to emerge that while gyms could reopen with 20 people per room as part of the “stage two” easing of restrictions, only 10 would be permitted in gym classes, including yoga.

That was despite Marshall enthusing just days before that 20 was the “magic number” for a range of venues, including gyms.

While the Premier never tires of telling us that it’s “much easier to put restrictions in place than to ease them”, the diffused prism of accountability has hardly aided that effort, and indeed has proven distinctly unhelpful for communication both within government and without.

Of course – of course! – governments should listen to “the experts”.

But, as Thatcher famously said, advisers advise, and ministers decide.

There was a bit of a joke going around public sector quarters early in the Marshall administration’s tenure that several ministers, wide-eyed at their first taste of government, had proven relatively easy to “house-train”, to use the Yes, Minister vernacular.

But of course, even then, advisers advised, while ministers decided.

Now, though, that joke has a worthy punchline – with the Government literally putting the advisers in charge.

Aside from Spurrier and Stevens, the Transition Committee is comprised of the heads of four government departments: Health, Treasury, Trade and Investment and Premier and Cabinet.

Can you imagine in any other circumstance a Premier or minister publicly refusing to make a decision on an important public policy issue because it’s up to the head of their department?

No, and why not? Because it literally inverts the intended hierarchy of the Westminster system of government.

So yes, it was easier to impose restrictions than it’s proving to lift them.

A significant reason for that, though, is that Marshall sensibly made public health advice the sole consideration when implementing lockdown measures.

In un-implementing them, the lines of decision-making are all over the shop, and if the cabinet is doing anything more than rubber-stamping Transition Committee edicts, they’re certainly not saying so publicly.

Moreover, the “health advice” upon which they’re relying is at the very least contestable.

In the early days of the pandemic, the SA Government leaned heavily on the advice of the AHPPC – the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee, on which each state’s chief public health officer sits.

This body was cited on a range of issues, most notably schools remaining open.

“The Premier could not be clearer,” his office said at the time.

“We are acting on the very clear advice from the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee on this matter – who are the leading experts on infection control.”

But the advice on schools, as it later turned out, was far from clear – with a review of evidence released by SA Health suggesting closing schools may reduce transmission rates for COVID-19.

The review of international evidence, ordered by Spurrier as part of her deliberations, revealed a “limited and mixed” picture, but included studies showing that children are at a similar risk of infection as adults and can transmit the virus to others.

“Studies of COVID-19 transmission (mostly peer-reviewed evidence) indicates that children are at a similar risk of infection as the adult population, that they have mostly mild symptoms or are asymptomatic, but can still transmit the virus to others,” the report stated.

“Modelling studies (non peer-reviewed, pre-print studies) suggest that school closures may reduce transmission rates in the community, and delay the peak of the epidemic, but may not reduce the height of the peak (cases per 100,000), and that school closures would need to be implemented in conjunction with other strategies for an extended period of time in the absence of a vaccine, or other effective control strategies.”

Then there’s the vexed question of border restrictions – finally addressed today with a blanket removal immediately after the midyear school holidays on July 20 (along with a vague insinuation of further easing before then), but which Marshall has previously repeatedly answered by saying while, of course, we want to ease border restrictions as soon as possible, we don’t want to go too early – so we’ll rely on health advice.

SA health advice, that is, because the national health advice doesn’t actually exist, other than public statements articulated by the likes of AHPPC member and deputy chief medical officer Paul Kelly, who said: “From a medical point of view, I can’t see why the borders are still closed.”

And fellow deputy medical officer Nick Coatsworth, who said it was “not clear what medical reasoning [there] is for state borders to remain closed”.

All of which could prompt a reasonable question: What’s going on in SA?

When the Federal Government said “open the borders”, local authorities maintained they need to stay closed on health grounds. Now they’re all to be opened, despite ongoing new cases in the major eastern states.

When national leaders say it’s too dangerous to hold public demonstrations, South Australia welcomes them. And then rejects them a week later.

And all of it based on generic “advice” to which we are never privy, or the whims of unelected bureaucrats.

New Zealand this week lifted all coronavirus restrictions bar border controls, in line with its published Elimination Strategy that sought to reduce new cases to zero (or a very low defined target rate) in a bid to eliminate transmission chains and prevent their re-emergence from cases that arrive from outside the country.

All of which SA achieved weeks ago.

And yet we maintain a state of emergency that empowers the Police Commissioner as our highest effective authority, leaves the Premier to rubber-stamp the decisions of his own chief executive and has thus far created a muddle of miscommunication, confusion and resentment.

So well may we say that it’s much harder to lift restrictions than impose them.

For presumably that’s why we’re doing a much worse job of it.

Tom Richardson is a senior reporter at InDaily.

Want to comment?

Send us an email, making it clear which story you’re commenting on and including your full name (required for publication) and phone number (only for verification purposes). Please put “Reader views” in the subject.

We’ll publish the best comments in a regular “Reader Views” post. Your comments can be brief, or we can accept up to 350 words, or thereabouts.