Richardson: The fraught politics of SA’s death spiral

The Government’s own population projections paint a grim picture – and could have a profound effect on the way we’re governed, writes Tom Richardson.

Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

I recall an old episode of Tom Baker-era Doctor Who wherein some unfortunate incidental character is ushered into a machine designed to accelerate time and is promptly aged to death.

Within seconds, the guy went from middle aged to ancient, and then to a rotting carcass.

I mention this because there’s a very real chance that the state of South Australia is heading for the same fate.

We know, of course, that SA has a rapidly ageing population, but that in turn is hindering its ability to regenerate.

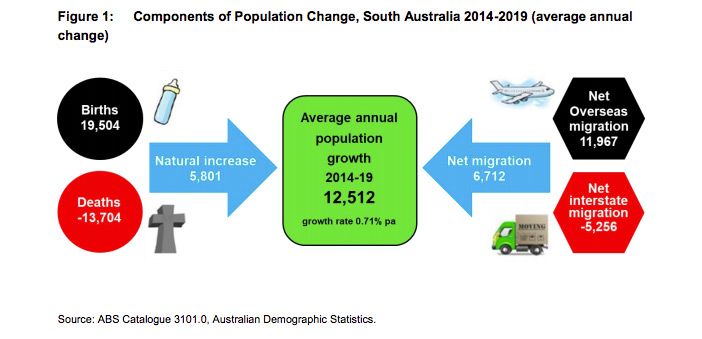

A paper recently submitted to the ongoing Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission hearings by the Planning Department highlights this, noting: “A significant demographic trend in SA is the slowly declining rate of natural [population] increase, which is caused by an ageing population (increasing death rate) and [corresponding] generally lower fertility rates.”

This decline is stark: the annual natural population increase has gone from 7200 in June 2014 to just 5300 in June last year, a remarkable 26 per cent fall in just five years.

And, according to the submission, that trend is projected to continue.

An excerpt from the report.

Little wonder that Steven Marshall has, very sensibly, emphasised the need for population growth via migration – a policy focus long overdue, after Jay Weatherill binned population growth as an explicit policy goal.

In fact, as recently as 2017, he said: “We’re not running a high population growth strategy… if you want to spend an hour and a half in traffic or spend over a million dollars for a home and actually deal with the crime and the dysfunction and the disunity that occurs in some of those other fast-growing places you’re welcome to it, but we like it here.”

Weatherill, of course, now lives in WA, having found his prospects for suitable employment limited in his home state.

As recently as 1982, SA had a higher population than WA.

It’s now about a million people behind.

Still, maybe he had a point.

When I lived in Melbourne in the early 2000s it had a little over three million people. That’s now more like five million – and the city has accordingly sprawled out like a concrete jungle.

While in Adelaide we’ve pretty much spent the same period pondering what to do with the old Le Cornu site.

Maybe our inherent development-aversion is apt for a state with marginal population growth – we build at the same pace we grow.

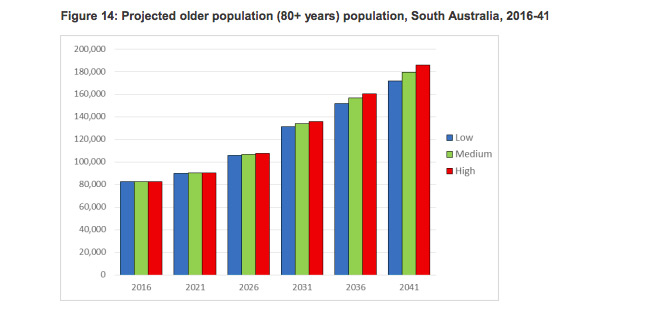

Another recent DPTI paper on population projections details that while SA’s population is nonetheless projected to increase over the next two decades, it will do so significantly more at the older end of the scale.

“Due to the ageing of the large post World War II baby-boomer cohort (born between 1946 and 1961 and aged 55-69 years in 2016), the fact that the fertility rates of this cohort were below replacement rates, and improvements in life expectancy, the state’s population is projected to age significantly during the projection period,” the study explains.

While projections of population growth in younger demographics vary wildly from low-to-high-end estimates, those for older South Australians are comparatively consistent.

“Under all series the population of ‘active retirees’ [aged 65 to 79 years] will increase from around 220,000 in 2016 to at least 310,000… by 2041,” the department finds.

“The increase will be most dramatic between 2016 and 2026 as the large baby-boomer cohort reaches 65-79 years of age, but is not yet affected by the higher mortality rates of old age.

“After 2026 the more dependent 80-plus age group is projected to increase more rapidly in size than the 65-79 age group.”

That demographic is expected to jump from around 90,000 now to around 180,000 by 2041.

By contrast, the preschool and school age population, for example, could remain relatively static – or even decline, under the most dire estimates.

An excerpt from the report.

It’s a death spiral: a growing population in the wrong demographics while simultaneously inhibiting prospects for future growth.

Not to mention the economic cost of such a population explosion in the 80-plus age demographic.

Then there’s the question of where the population is growing – and where it isn’t.

Most – almost 80 per cent – of the state’s total growth is, unsurprisingly, in the Greater Adelaide metro area, with the inner and outer northern suburbs experiencing the biggest increases.

By contrast, many of the regional areas remained relatively static, with the Eyre Peninsula and South West region experiencing steady population decline over the past few years – a continuation of a longer term trend.

It’s worth noting, given this data is being considered by a body established to draw up SA’s electoral map, that most of the seats in the inner and outer north are traditionally Labor, while almost all the regional electorates are strongly Liberal.

Still, the boundaries commission is there to ensure both parties have an even chance of electoral success, which suggests the map could look very different in a few years time.

For starters, it seems inevitable – given the legislative requirement to maintain the same number of electors in each seat, within a ten per cent tolerance – that a regional seat could be abolished before too long, and replaced with another metro one.

In terms of the mandated 47 seats, this won’t make any difference.

It may not, moreover, have an impact on deciding who forms Government (although it might).

But where it could have a lasting legacy is in the makeup of the Liberal partyroom.

Conservative rural Liberal MPs join the Labor benches for a vote in 2018.

Since the Marshall Government took office, there has been a clear disconnect between the Liberal Party’s regional representatives and its metro MPs.

This tension was perhaps best encapsulated when four MPs – Fraser Ellis, Steve Murray, Dan Cregan and Nick McBride – crossed the floor to protest planned changes to the Mining Act, arguing the legislation was unfair to landowners in farming communities.

Two of those dissenters – Ellis and McBride – represent regional seats, while Murray hails from one and Cregan’s electorate is peri-urban.

Given that former Liberal conservative Troy Bell, from Mount Gambier, also voted with the renegades, and that cabinet’s sole Right-wing inclusion Stephan Knoll represents the Barossa seat of Schubert, it’s not a stretch to suggest a close correlation between regional and factional divides in the Liberal party-room.

That metro-regional tension has been evident in other internal debates, including last year’s land tax kerfuffle.

The loss of a regional seat, then, could mean a significant shift in the power balance of the Liberal party-room, given a moderate-dominated metropolitan branch would be disinclined to preselect a regional SA-promoting conservative.

Still, a slow decline in representation across the board is unlikely to do much for the reinvigoration of SA’s regions, which makes the current population projections appear ever more inexorable.

Which makes it hard to conceive that, in two decades time, we won’t be still mourning the burgeoning generation of ageing baby-boomers while lamenting the lack of a subsequent baby boom, concertedly vying with Tasmania to avoid leading the nation’s unemployment stakes – and, most likely, still discussing what to do with the old Le Cornu site.

Tom Richardson is a senior reporter at InDaily.