The fairness paradox: debunking the SA Liberals’ electoral claims

With senior South Australian Liberals preparing to fight for a return of the “fairness clause”, Labor party lawyer Adrian Tisato argues that their claims about the state’s electoral system don’t stand up to scrutiny.

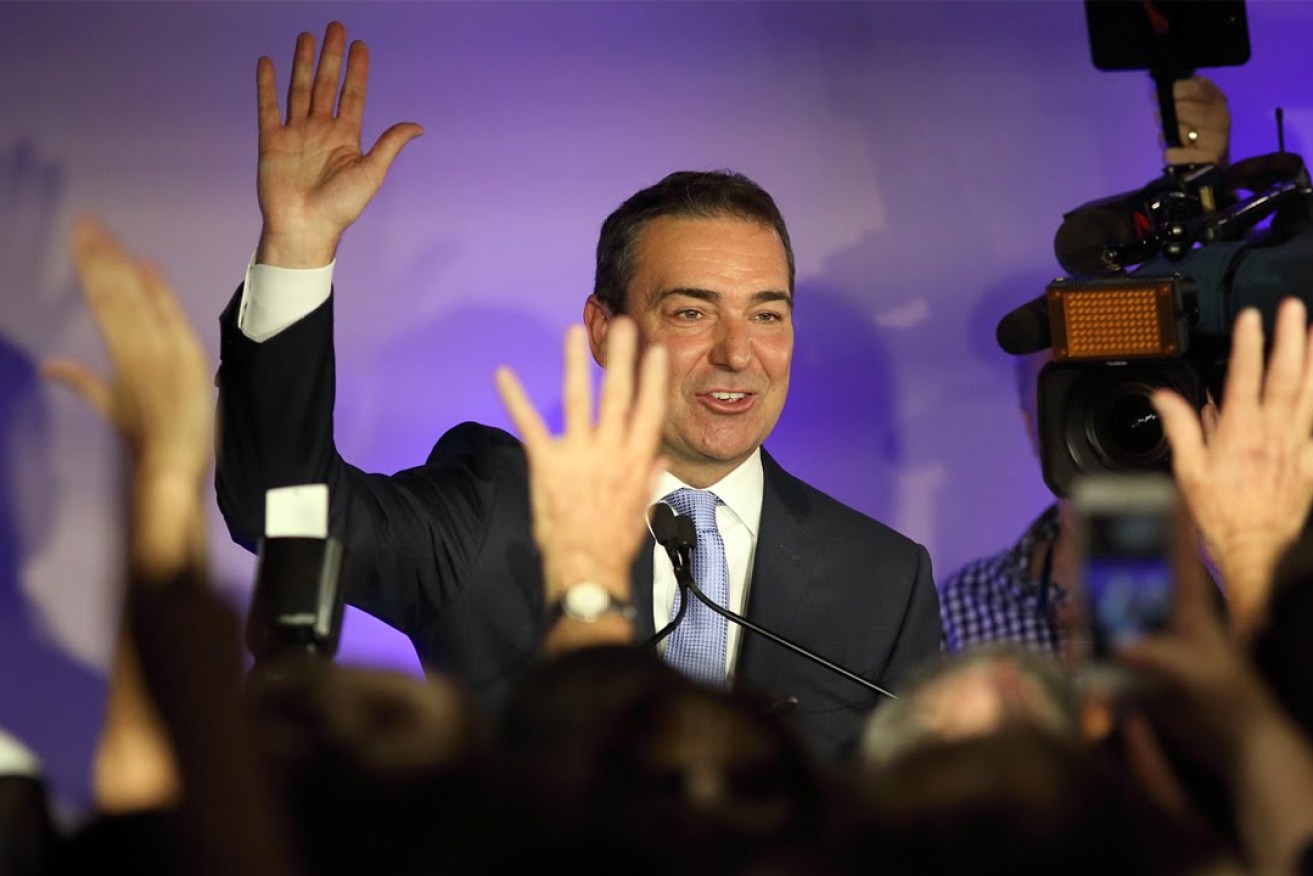

Steven Marshall on election night 2018. Was it really the first fair election in decades? Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

In 2016/17, the Liberal Party in South Australia mounted a campaign to complain about being in opposition for four terms. Their argument was that, but for the electoral boundaries, they would have been in government.

Now, a short time before the Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission is due to begin proceedings to redistribute the electoral boundaries for the 2022 election, we see the Liberals mounting the same campaign.

First, the Liberals’ lawyer and former vice-president, Morry Bailes, wrote an InDaily opinion piece on the topic.

Now the Government has announced it wants to reintroduce the so-called “fairness clause” into the Constitution Act.

Essentially, the Liberals make three claims.

First: They were kept out of government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018 because of a “gerrymander” that favoured Labor. This was despite South Australia’s Constitution Act having a “fairness clause” in it that was meant to prevent such a thing occurring.

Second: The 2016 boundaries commission was the only one that correctly applied the “fairness clause”. All previous commissions failed to do so.

Third: In the last Parliament, Labor sneakily removed the “fairness clause” from the Constitution Act with the support of crossbenchers. The loss of the “fairness clause” will increase the likelihood that the commission will set electoral boundaries for the 2022 election that will again be “unfair” to the Liberal Party.

Each of these claims is wrong. The public should not be misled by them.

Since 1991, in every election except one, the electoral boundaries produced a fair result: the major party that won the popular vote also won the two-party-preferred vote in a majority of electorates.

The commission does not need the so-called “fairness clause” to set fair electoral boundaries. South Australia is better off without the clause and should be relieved that it is gone.

To understand why, we need to lay out the facts.

The “Playmander” years

From the 1930s to the 1960s, the Liberals governed for 32 years using their legislative majority to manipulate the electoral boundaries to give themselves a huge advantage over Labor. This became known as the “Playmander”.

Under this system, two thirds of the state’s population lived in the city but two thirds of the state’s electorates were in the country. City electorates had as many as 10 times the number of voters in them as country electorates.

To put it another way, a country voter had up to 10 times more say in who governed than a city voter.

1975 – one vote, one value

In 1975, a new system for setting the electoral boundaries was introduced.

The Parliament:

- Introduced section 77(1) into the Constitution Act, known as the “one vote, one value” clause; and

- Created the Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission – an independent commission – to ensure that never again would the government of the day be permitted to manipulate the electoral boundaries to stay in power as the Liberals did in those earlier decades.

The commission’s task is to reset the electoral boundaries to account for population shifts across the state, so that the number of voters in each electorate is close to equal (within a + or – 10% tolerance).

1991 – the so-called “fairness clause”

In 1991, the Parliament introduced section 83(1) – the so-called “fairness clause” – into the Constitution Act.

The clause was drafted by political scientist, Malcolm Mackerras, at the request of the Liberals.

It sought to impose a proportional representation concept over South Australia’s single-member electorate system.

While this was well-intentioned, it set the commission a “virtually impossible” task, according to the University of Adelaide’s Professor Clem Macintyre, in the evidence he gave to the last commission. He said the “fairness clause” was “not practicable”.

Even Mackerras has disavowed it. In 2016, he told InDaily it was “a silly clause … of which I’m not proud – it’s just a silly idea and I should never have entertained it”.

He attributed Labor’s sustained electoral success to its superior campaigning.

No gerrymander

Labor has never won an election in South Australia thanks to a gerrymander.

By definition, a gerrymander is a deliberate, partisan act of manipulation by the political party in charge: a rigging of the electoral boundaries with the intention of producing an election that favours them over their opponent. There is no such thing as an accidental gerrymander.

Any suggestion that previous commissions rigged the electoral boundaries, in a calculated and deliberate act to give the Labor Party an unfair advantage over the Liberal Party, would be without foundation. It would be a surprising and unjustified attack on the integrity and independence of those previous commissions.

What is fair?

Did the major party that won the popular vote also win the two-party preferred vote in a majority of seats? If so, the electoral boundaries produced a fair result.

There has only been one election in which Labor won a majority of lower house seats without winning the popular vote. That was the 2010 state election.

One week after that election, a senior Liberal MP and former Liberal Party leader, Martin Hamilton-Smith, blamed the loss on the Liberal Party itself, not on the electoral boundaries.

The other elections that the Liberals claim produced an “unfair” outcome are the 2002 and 2014 elections.

They are wrong on both counts.

In both 2002 and 2014, the Liberals won the popular vote and won the two-party-preferred vote in a majority of seats in the House of Assembly.

The problem for the Liberals in 2002 and 2014 was that they had lost control of seats they had previously held.

In 2002, three seats previously held by the Liberals were won by former Liberals who had become independent MPs. A fourth was won by a Nationals MP. In each of these four electorates, voters voted overwhelmingly in favour of the Liberals on a two-party-preferred basis. However, one of the ex-Liberals unexpectedly supported Labor to form government. One of the others became a Labor Cabinet Minister, as did the Nationals MP. The other ex-Liberal eventually became Speaker under Labor.

In 2014, two seats were won by independents – one of whom was a former Liberal, while the other was an independent MP who had won a safe Liberal seat from the Liberals in an unnecessary and ill-advised by-election. In each of these two electorates, voters voted overwhelmingly in favour of the Liberals on a two-party-preferred basis. One of those independent MPs supported Labor only after the other fell gravely ill and withdrew from post-election negotiations.

The fact that the Liberal Party did not win these seats, that independent MPs in conservative electorates backed Labor to form government or that an independent MP became ill in the midst of post-election negotiations, had nothing to do with electoral boundaries. These were events that the commission could not predict or control.

Mike Rann claims victory in the 2006 “Rannslide” election. Photo: AAP/Rob Hutchison

Our single-member electorate system

As a single voter, you or I only vote to elect one MP to the House of Assembly.

We have no say over who will win the elections in the other 46 electorates. Nor do we control whether a Member of Parliament we elect will remain a member of their own political party during their term in Parliament.

For example, hypothetically, if Liberal MPs Sam Duluk, Dan Cregan, Nick McBride, Fraser Ellis and Steve Murray were to quit the Liberal Party in the next two months because of the Government’s land tax and mining reforms, these MPs would remain in Parliament as independent MPs.

And if, at the 2022 election:

- all current MPs in the lower house were re-elected;

- the Liberals were to win the same state-wide, two-party-preferred vote they won in 2018 (52%); and

- independent MPs Duluk, Cregan, McBride, Ellis and Murray were to throw their support behind Labor leader Peter Malinauskas,

Then, Labor would form government with the control of 24 seats but with only 48% of the state-wide, two-party-preferred vote.

This is where the Liberal Party complaints about electoral boundaries would kick in.

According to the Liberals, such a result would be “unfair” because they would have won the popular vote, yet Labor would have “won the election”.

A gerrymander!

They would argue that the seats won by independent MPs Duluk, Cregan, McBride, Ellis and Murray – all safe Liberal seats on a two-party-preferred basis – should now be regarded as “Labor” seats on the Liberal/Labor pendulum.

They would urge the commission to radically redraw the boundaries for the 2026 election to make them more favourable to the Liberals, to ensure that if the Liberals were to win 52% of the two-party-preferred state-wide vote at the 2026 election, they would win a minimum of 24 seats in their own right, without having to rely on the support of independents MPs.

And they would argue that the commission should deliberately place fewer voters in Liberal seats and more voters in Labor seats to fix the “mistake” that was made by the commission that set the 2022 boundaries.

How do I know this? Because this is what the Liberals argued at the last commission when complaining about what they claimed were “unfair” Labor election “wins” in 2002 and 2014.

What the Supreme Court decided

Mr Bailes says that the last redistribution established that the methodology used by previous commissions was an “error in approach”. Current Treasurer Rob Lucas has told Parliament that “for 30 years” – until 2016 – the commission did not properly apply the “fairness clause”.

This is not what the Supreme Court found when it decided the case in 2017.

The court did not criticise or reject the methodology of previous commissions.

While it found that the 2016 commission was entitled to place more voters in Labor electorates and fewer voters in Liberal electorates to achieve the “fairness clause” outcome, the court also ruled that the commission was entitled to have regard to the desirability of numerical equality across districts – even with the “fairness clause” in force.

Facts over politics

It is time that the Liberals’ claim – that they were kept out of government for 16 years because of unfair electoral boundaries – is exposed for what it is: a political claim, not a factual one.

Take, for example, Mr Bailes’ claim that, thanks to the Supreme Court’s decision, the 2018 election was “the first truly fair election in South Australia for decades”.

Seriously? At the 2006 election, Labor won 56.8% of the two-party-preferred state-wide vote and won a majority of seats in the lower house. How was that unfair to the Liberals?

To claim that unfair electoral boundaries illegitimately cost the Liberals “election after election … for decades” not only diminishes the Liberal Party and its capacity for self-reflection, it diminishes our democracy.

How and why was the “fairness clause” repealed?

Finally, the Liberals’ claim that Labor, “with the support of crossbenchers, snuck through an amendment to the Constitution Act” that removed the “fairness clause” from the Act is also factually wrong.

Labor did not propose the amendment. The Greens did. The Greens argued that the “so-called fairness clause”, as they have always called it, has always been unfair to minor parties and independents.

Labor and one other crossbencher supported the Greens’ amendment.

The future

Now that the problematic so-called “fairness clause” is gone, South Australians can breathe a sigh of relief. It was an experiment that caused no end of mischief and controversy.

The unenviable task it imposed on the commission should henceforth be known as the “fairness paradox”.

Without it, South Australia now has a system for setting electoral boundaries that is in line with the federal electoral system.

And the commission can get on and do its work in a straightforward way.

May the best candidates and best policies – rather than the electoral boundaries – determine the winner.

Adrian Tisato is an Adelaide-based commercial lawyer. The South Australian branch of the Australian Labor Party is one of his clients.