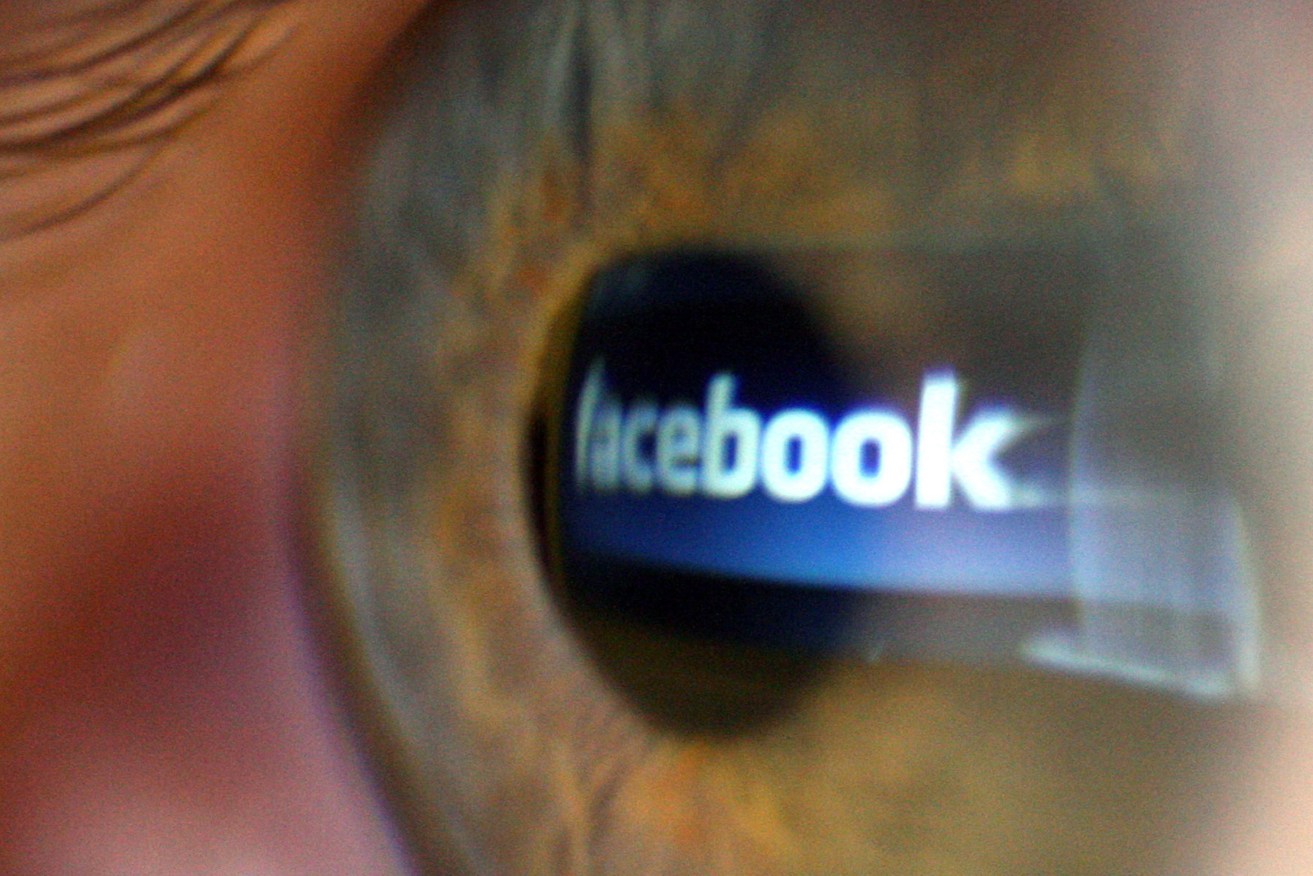

Surveillance capitalism is Orwell’s nightmare

From Facebook on our phones to CCTV in our public places, a booming culture of constant surveillance is threatening our freedom, argues Adelaide writer Stephen Orr. Why, then, do so few of us care?

Photo: Dominic Lipinski/PA Wire

George Orwell’s 1984 is coming along very nicely, thank you very much.

Groupthink is up and running, courtesy of Facebook, Twitter and other “social” (hardly) media. Here we can gather, agree on an accepted position, entrench it, defend it, destroy anyone who doesn’t agree. We can feel good about our sense of always-right, like a tribe of Saturday morning Jehovah’s Witnesses trying to convince those who haven’t seen the Light.

This extends into a mass media that has become dumber than dumb, propagating an inane world-view that so many take as Crows-gospel. Newspapers that keep it light, and easy, while governments are intent upon convincing their citizens that everything is just peachy (plenty of jobs, plenty of places for the kids to kick the footy).

“It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words.”

Newspapers assume we’re all 11-years-old; English courses no longer require kids to read novels; governments produce copy that resembles (and is) Newspeak – political lies re-packaged as promises. The problem being, as Orwell explained: “The choice for mankind lies between freedom and happiness and for the great bulk of mankind, happiness is better.”

So let me lay my cards on the table. As a purveyor, a refiner, a diviner of words, I fear for the future. Mostly, a world in which citizens are so paralysed by fear – so busy trying to pay taxes to subsidise the technocracy, so distracted by the promises of technology, so angry they spend their days seeking others to blame for their despondency – that they don’t see the big picture: a world in which, removed from the communities, the values, the relationships that used to nourish us, we succumb to the future through a mixture of apathy, tiredness and ignorance.

All this is happening, despite the fact the warnings are there, and we do – at present – have the ability and the rights to shape our futures into something human, fair, democratic.

You are Orwell’s Winston Smith, someone who felt “the urge to shout filthy words at the top of his voice …”

It starts small. Me, sitting on a step with my eighteen-year-old son, waiting for my other son, outside a city store. A security guard, early twenties, tells me I can’t sit on the step. I ask him why, and he seems surprised. I explain there are no signs saying I can’t (signs seem very important in a regulated world).

Maybe it looks a bit sloppy, but old people have to sit somewhere (as they are surveilled by the dozens of cameras along Rundle Mall). But he’s young, and ‘just trying to do a job’, so I stand and wait. Then he looks at me and says: “What are you doing here, anyway?” I reply: “Pardon?” He says: “Why are you here?”

The old Glasgow genes kick in, and I say: “‘What’s that got to do with you?” He says: “Why can’t you move on?”

Of course, at this point, I could’ve told him I’m waiting for my son (and to fuck off), but I thought: Why do I need to explain my (lack of) movements to you? So I said: “You do understand that people are allowed to stand and wait? Unless you’re a police officer, and have cause to move me on, the reason I’m standing here has nothing to do with you.” At which point he thought better of it, turned, and retreated to the shadows of his self-scripted, never-quite-made-it-into-the-police-force existence.

Point being, his assumption that a well-dressed, 51-year-old teacher-author was some sort of trouble-making arsehole because he wasn’t willing to succumb to some (pathetic) form of authority.

Which brings me to my gripe-o’-the-day. Our habit, as a species, of giving in to what we see as inevitable. In this case, a well-ordered, efficient society where everyone obeys every directive. Again, strange, because history shows (try Germany, 1938) that the accepted version is not always the best. It seems that the rise of apathy goes hand-in-hand with the perfection of technology. If we’re pacified, if we’re encouraged to re-Tweet Paris Hilton’s lips, if we accept organised sport as Polyfilla for the spiritual vacuum caused by the Death of God, if we buy government spin about our state becoming some sort of World Rocket Headquarters, if we blindly accept Authority as Truth, this is our future.

Capitalism is bored. It used to make stuff, but then off-shored it. Eventually, it imported the slaves and made them deliver food. It made phones and flogged new models every two years. But then it got to thinking – there’s a limit to this (and we know that capitalism doesn’t like limits). So it said: “Here’s an idea. Let’s convince every government in the world that they need cameras, shitloads of them, drones, surveillance, in every shape and form imaginable. Not only that, but what about markets for behavioural data, harvested for free that (according to Shoshana Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism) ‘allow interested business customers to lay bets on what we will do now, soon and later’?”

This is an Orwellian vision of the future that Guardian journalist John Naughton calls “a new mutant form of capitalism that has found a way to use tech for its purposes”.

Photo: Universal Images Group

Zuboff, who’s been charting the rise of Surveillance Capitalism (SC) for over a decade, explains: “First of all there was the arrogant appropriation of users’ [Facebook, Google] behavioural data … then the use of patented methods to extract or infer data even when users had explicitly denied permission.” We all went along with this because the internet was shiny, and new, and the cat videos were so funny. But then came “the use of technologies that were opaque by design and fostered user ignorance”.

Now, things are changing, cats aren’t so funny, and we get the sense (or should) that technology is not necessarily our friend. That it will happily automate hundreds of millions of jobs, distract us from a complex world, all the time reassuring us (because it’s neat, isn’t it, how you can bank online, read the latest book without waiting, order shoes without trying them on) of a happy-life-to-come. We had some sense that corporate nasties like Google were a little naughty, doing things like digitising the world’s libraries without paying actual authors and publishers. So what? Western Civilisation, blah blah. Get with the future.

Future? Well, look at China. Here’s Yu Yan, sitting in class in the 11th middle school in Hangzhou. She looks out the window at a flock of birds and notices one flying strangely (bird drones, already used in five provinces in China). ‘Yu Yan!’ her teacher calls. ‘Pay attention!’ (He could tell from the cameras installed above the whiteboard as part of the ‘Smart Classroom Behaviour Management System’).

That night she goes to the Jacky Cheung Cantopop concert, but her friend is arrested when recognised by the Ministry of Public Security’s facial recognition system. Jaywalking on the way home, Yu Yan’s face is screened above the intersection with a warning. She tells her father, but he’s too tired to care after a day (having his brainwaves recorded by a wireless sensor) at the Hangzhou Chonghen Electric factory. All of this, of course, conducted in the context of China’s social credit system, a society of well-trained whistle-blowers, and citizens whose every online word, and thought, is monitored.

Traffic police use facial-recognition technology to capture jaywalkers in east China’s Jiangsu province. Photo: Wang feng – Imaginechina/Sipa USA

But China’s not alone. The spread of surveillance is rapid and seemingly unstoppable. The Lockport city school district in New York is presently setting up facial recognition systems ready for the new school year in September.

Superintendent Michelle Brady explains: “Much to our dismay school shootings continue to occur [involving] students connected to the schools …” Ipso facto, get out the cameras and screw with everyone’s privacy. But as Lockport parent, Jim Schulz, put it: “The way the system is designed to work is you would have to know in advance who the school shooter would be – you’d have to get their picture and put it in the system, and you’d have to hope they didn’t put on a ski mask or something. Even then, an alert would be unlikely to stop an attack in time.”

The ski mask. Sure sign of a deranged school shooter. Maybe a fair alternative to creating happier, well-adjusted kids with a positive view of the future. Or is that too much to ask in Trump’s America? Better to arm the teachers? That way, everyone gets a slice of the coming dysfunction. Because that’s the issue, isn’t it? The idea that you can be standing, minding your own business, and for some unknown reason, you are the villain. You are Orwell’s Winston Smith, someone who felt “the urge to shout filthy words at the top of his voice …”

East London, 16 May 2019. A man walks down a street, and someone tells him there’s a facial recognition camera up ahead. He covers his face, but when he approaches the camera he’s taken aside by police, photographed, fed through the system and given a £90 fine. He says to one policeman: “How would you like it if you were walking down the street and someone grabs your shoulder?” A young woman questions the police and receives the predictable reply: “The fact that he covered his face gives us grounds to stop him.”

When did walking become grounds to do anything? Is this a taste of the future Orwell described? A few people stood up for this man, but not many. Most just walked on, not wanting to get involved.

Privacy. Eroding. The feeling we get when we post free content online, when we search for cashews, and the internet knows we like cashews. And the strangely ridiculous notion that whatever we do behind closed doors, wherever we stand, is our business.

Strange to think that Orwell understood the end, but could never have imagined the means.

According to Zuboff, it would take 76 days to read all of the privacy policies we encounter in a year. Cleverly done.

In the end, Winston Smith escapes a world “where there is no darkness” by meeting his lover in secret. Is that all we have to look forward to?

Stephen Orr’s latest novel, This Excellent Machine, is a coming-of-age novel in the most fibro tradition.