When it comes to justice, popularity is irrelevant

There are good reasons why our judiciary must not be swayed by public opinion, writes legal commentator Morry Bailes.

The full bench of the High Court is set to make two crucial decisions. Photo: AAP/Lukas Coch

Justice is not a popularity contest.

Andrew Langdon QC, Chair of the Bar of England and Wales, recently employed this expression and it serves as a timely reminder to all Australians as we debate the merits of the same-sex marriage plebiscite, Canberra’s dual citizenship row and witness the media feeding frenzy on both.

For while the nation argues, it is the High Court of Australia that will soon interpret and rule on these two constitutional questions – the results of which will impact the government and social fabric of the nation. The first relates to the interpretation of section 44 of the Constitution dealing with citizenship of a foreign power and eligibility to sit in our parliament. The second is the constitutional validity of the postal plebiscite relating to the question of same-sex marriage.

Each of these decisions will be remarked upon and scrutinised in detail by our media, as well as the punter having a drink at the local bar. Some commentary will be well informed. Some, inevitably, will not.

This is why we must remind ourselves that justice is not a popularity contest. Mr Langdon used the expression when writing to defend barristers involved in the Charlie Gard case in Britain. Charlie Gard, now deceased, was a congenitally ill baby whose parents wished to take him to the US for treatment but who were denied by the court, which instead ordered he must remain in a UK hospital. The press imputed that the barristers briefed acted on their personal views.

Mr Langdon dealt with that by pointing out the role of justice and of barristers. First, he remarked on the “cab rank rule”. Barristers don’t get a choice in what they are briefed, and must take what is offered if they are at the top of the queue. “A barristers professional code requires them to accept instructions to act in cases in which they have the necessary expertise and seniority, irrespective of the identity of the client, and any belief or opinion…”

Then he drew our attention to the obvious. Both sides need to be represented to get a fair hearing. In unpopular criminal cases there is apparent, perhaps wilful, disregard for the fact that irrespective of the crime alleged, for a proper trial to be conducted, someone has to represent the accused. The fact that the barrister may find the case against the accused distasteful, or the alleged crime reprehensible, is irrelevant. The mere fact that one side of the case is unpopular is also irrelevant, as with the Charlie Gard scenario.

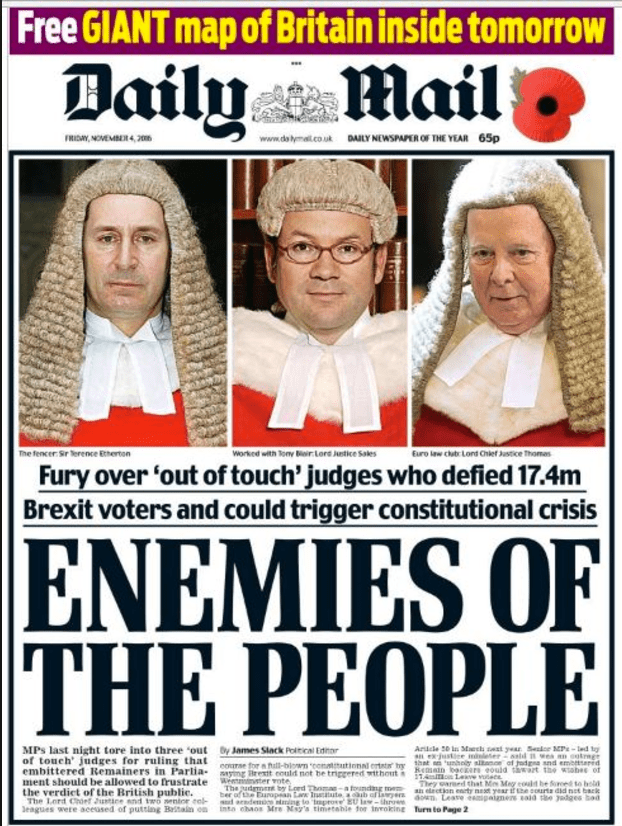

The same, of course, applies to the judiciary. The reaction of the British press to a recent High Court decision, that found parliament needed to legislate to legitimise the Brexit referendum, was extraordinary, even by Fleet St standards.

Even by the standards of the British press, this was low.

Each of the judges was singled out for totally irrelevant and unnecessary comment, including that one was “openly” gay and was an ex-Olympic fencer. Wow, that was obviously of great pertinence to his decision-making. The Daily Mail headline declared the bench of judges “enemies of the people”. It was “the judges versus the people”. All of this was nonsensical vitriol because the decision was unanimous and correct, even though to some it was unpopular.

Criminal sentencing can bring about the same irrational commentary, but not always. I read recently a report of a relative of a victim of crime expressing her disappointment with the sentence but acknowledging that within the confines of the law the court had done the best it could.

Therein lies part of the point. Parliament makes laws, courts interpret them. Oft times parliamentarians remain steadfastly silent when they well know that an outpouring of anger at a judicial decision has to do with the adequacy of the law passed by the parliament – not its application by the court. In days past, the first law officer – the Attorney-General – had the job of defending the courts. There is, disappointingly, an erosion of that convention and a necessity for others to step in to educate the public about the role of justice and to remind us, as Andrew Langton did, that it is not a popularity contest.

As our barristers go about the job of representing parties in often difficult and unpopular cases, let us be reminded that justice is about fairly representing a party before an objective and impartial decision-maker. It is most certainly not about doing what is popular or being in the slightest bit influenced by doing what is unpopular. The court of public opinion is, and remains, in the press and in the pub. The court of fairness, equity and law is the judiciary, supported by our legal professions.

Mr Langdon concluded his remarks by reminding us that taking cheap shots at our system of justice has a price.

“What is not cheap,” he says, “is the cost to the reputation of our justice system, and the personal price paid by professionals who are exposed to threats and vilification for having done no more than discharge their professional duty.”

We have a very good justice system. We must work to maintain its viability and fight to ensure we all enjoy equal access to it. But at the end of the day it is independent as it is excellent. So when everything that falls from it is not a winner in the popularity stakes, always remember that justice is nothing to do with what is popular, it is about what is right.

As Francis Bacon once remarked: “If we do not maintain justice, justice will not maintain us.”

Morry Bailes is the managing partner at Tindall Gask Bentley Lawyers, president-elect of the Law Council of Australia and is a past president of the Law Society of SA. The opinions expressed in this column are his own.