Requiem for a school

Is a bigger school better for smaller people? Author Stephen Orr (writing as The Poet) thinks not, as he laments the loss of his old primary school at Gilles Plains and the memories it rekindles of gum nuts, mad dogs, marbles and square dancing.

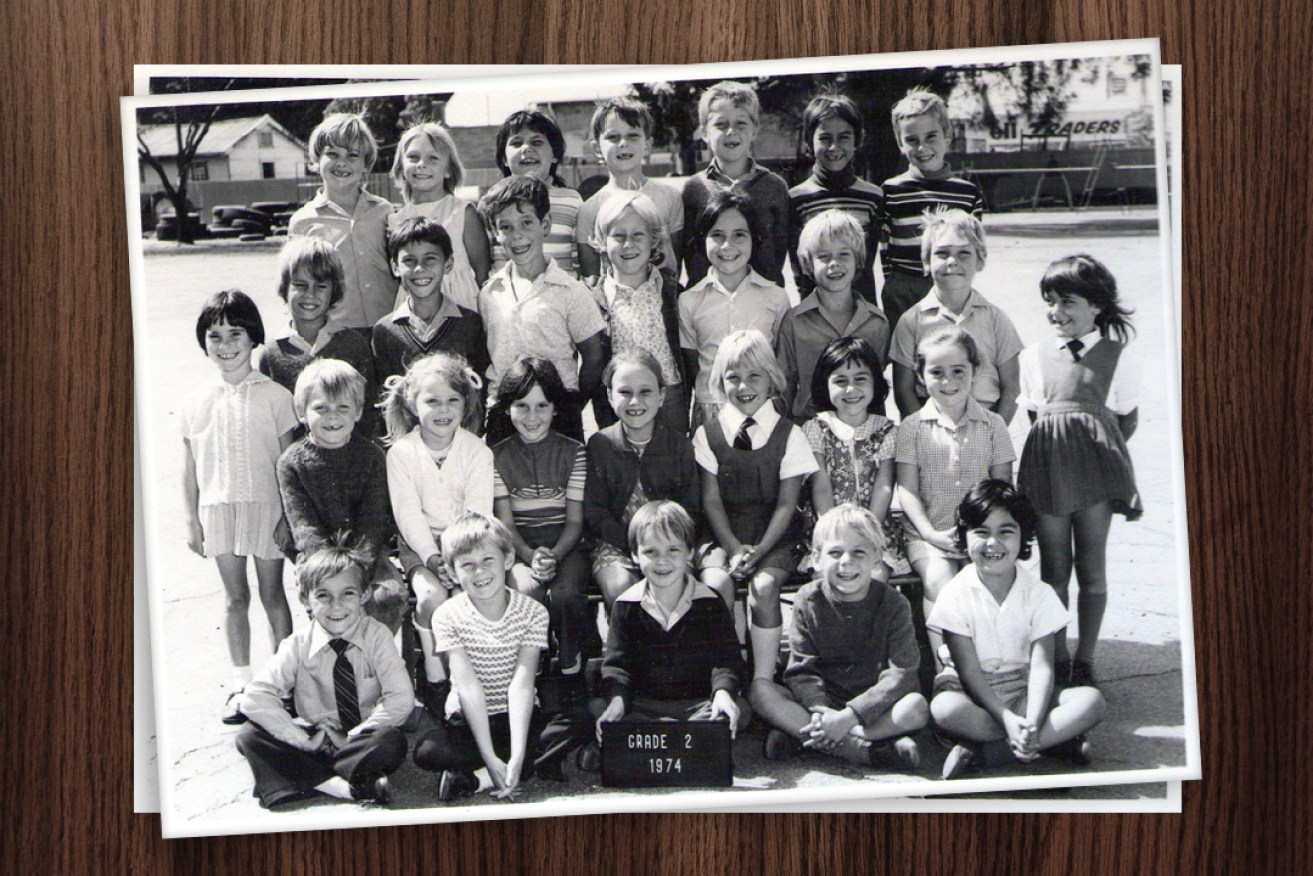

School days: Stephen Orr (The Poet) can be spotted in the middle of the back row.

Having heard his primary school was closing (to be amalgamated with a nearby high school), the Poet returned, looking for reasons, memories. Something inexplicable was drawing him. The State had decided. Not in a reasonable way, he thought, and this filled him with anger. More, a sly, underhand way, which typified most of their actions.

With this latest (bad) news, the Poet wanted to see his primary school one last time before it was bulldozed. It was a warm Saturday, and he rode past. Noticed the infant school had gone, the shed where he’d eat his half pie and chocolate doughnut, drink his school milk, all gone. The old canteen that had once been the school itself. Where you could get tomato soup. Lollies. Before the regime had decided against them.

All at once he felt melancholic. This process of closing, shifting, downsizing (in line with the State’s policy of economic rationalisation) had been going on for some time. Indeed, as he rode further, he noticed that many of the buildings in which he’d first learned his native language had also gone. And further, half of the oval (like one of his too big pies), sold off for housing. As the melancholy turned to anger.

Frankly, he wasn’t surprised. The Director had been riding roughshod over the population for years. Withdrawing services (most recently, closing and amalgamating public hospitals) while, at the same time, building up a loyal voting bloc of public servants. If this tumour-like growth was to continue, services would need to be cut. The Director had compensated with lashings of propaganda. A minister appointed, advisors, a generous budget set aside to convince the plains dwellers that theirs was a fortunate lot. Manufacturing consent, even going as far as convincing the population to accept the world’s nuclear waste.

The Poet’s school was targeted for falling enrolments. The truth of this couldn’t be argued. But the Poet believed this in itself was a result of years of inaction. The Partido del Trabajo had explained that it was ‘excited’ to create a new school that would ‘serve the burgeoning population in this area’, all the time failing to explain why the primary school had performed so poorly in the first place.

The Poet had attended a meeting at the local high school (with which his primary school would amalgamate) that had been convened to decide the future of his small school. And all he’d heard was talk of closing, amalgamating, the benefits that would accrue to the students of his old school. He’d argued. Wasn’t this meeting to discuss options? Ways to avoid the end? More public servants had been sent his way, to make him see sense, but he’d just become angrier (and all this time, wondered where the others were – those who risked losing the past, the Word, the Idea). All the time, the official mantra: What’s best for the children. Although, again, this was never explored, as if, somehow, a bigger school would be better for smaller people. The Poet believed otherwise (seedlings always did best in a nursery).

So the Poet had returned. He wanted to look through his old school, but the State had built a tall fence around it. He saw the bitumen where a pattering Mr M had made him and his classmates practice square dancing (‘Circle eight and you get straight, And we’ll all go east on a westbound freight…’). He felt sad that those days had gone (although remembered feeling differently at the time). Mr M, smoke in hand, calling them to take their partners, stop complaining about the hundred degree heat. The grass that had once been the Senior Open Unit (all the rage in those days). Where a different Mr M, all moustache and yellow bird, up high in banana tree, had first praised his speed and accuracy skills (he still had the certificates). He remembered how this Mr M had sent him (little knock-kneed him) up the hill where the local cars were made, to the music shop, to buy an E string. The feeling of freedom, the trucks and buses speeding past, and the knowledge that he was the only one trusted to walk so far. And that feeling returned now. So proud. For seven long years. Knowing he was valued, and loved. Even by the teachers. Good people he’d remember to his last breath.

Which made him angry, again. The previous Friday, sitting with coffee, reading that the State had decided: the school on the plains must go. But how could it? It’d been teaching children since 1901. He remembered the photo hanging in Reception: Edwardian boys and girls sitting in old clothes, some, the grimiest, with bare feet, but with a look of wanting to learn. They, their parents, knowing they were guaranteed a quality education.

Then he descended. There, that room there! Mrs C. She was the best! An old English woman with a tank of yabbies, who praised his cursive (still used, every day). He wondered where she was now. Dead, most probably. But wanted to thank her. Funny, he thought, how you only remember to say thanks years later. Feel bad that you can’t. But sadder, that the whole school would soon be gone. The day the mad dog got in, and they were kept in their rooms, until their old gringo came for it, put it on a leash, took it away and shot it.

Yes, angry. For, as the meeting had progressed, and he realised no one was listening to him, he’d said aloud: ‘Maybe the school could wait, try different teaching programs, market itself differently, wait until numbers pick up (he knew that populations ebbed and flowed).’ But again, he’d had the feeling these things had already been decided. He’d learn this, later, when the State announced the new school would start operating six months after he sat, coffee in hand, reading the bad news. Six months? How could anyone replace a school so quickly? He had the feeling he was being patronised, patted on the head, sent on his way (as the various state-sponsored revenges were devised).

He rode around the school, but couldn’t get in. Even the oval, locked away, at odds, perhaps, with the State’s message of young bodies in motion. But all messages were mixed. The Director’s school reading challenge, as the State Library was stripped of a fifth of its staff. Things that didn’t add up. Writers punished for suggesting the Director was naked.

But the Poet wasn’t that easily put off. He left his bike on the blue metal where he’d once skinned his knee. Slipped under the high fence, and went into his old school. The big glass doors of the pebblecrete building. He looked in. Not so different. Sport equipment and macaroni artwork and a poster of the Director throwing a ball to a girl. Up the stairs, and although he couldn’t see, he remembered the library. Which, to him, still, was a kind of womb, away from the bullies and big boys these new Poets would have to face at their new school. Still, the Director would take care of everything. A womb in the sense of Asterix and Storm Boy and the various worlds that worked in counterpoint to his own. A thousand lunches. More perhaps, as Mr J, the librarian who always wore a skivvy and showed them films about his trips to Greece, said, ‘You, J, have you read this one yet?’ He wondered if there’d be another Mr J, at the new school, and whether he’d care as much. Of course, at least that was certain.

The Poet wandered to the next door. Reception. Here, he sold pencils and sharpeners before school (only the older children were trusted with money). He fed Mrs C’s yabbies in the staff room. Alone, he felt lost in this spirit-smelling place, with its Best Bets and unemptied ash trays. He reported to the sick room for dry pants, when the others were, well, wet. Here, also, the office, when he and three others had been caught throwing gum nuts over the neighbour’s fence – all lined up, shaking in fear of the cane. He suspected he saw the same aspidistra in the same copper pot. But how had it survived these 36 years?

What the parents want, the newspaper article had said. But this seemed to suggest only good could, and would, come from closing, amalgamating, selling off land. There would be better resources at the new school. But how many six-year-olds cared about chemistry labs? So, he’d compared this article with the Education Minister’s press release, and realised the information had been transcribed. The minister says a, the paper says a. Like there wasn’t, and never could be, an alternative. As the Poet remembered Winston Smith, and his job, presenting the news that government favoured. All the time, the assumption, that the population was uncritical, or uncaring (busy as it was with the perfect dessert). That they would trust a government that had, at one time, been worth trusting.

And then, the Poet sat in the sun, closed his eyes, and listened. He could hear a game of marbles, and singing, and someone calling someone else spastic, in the days when that’s what you did. He realised, now, he was wasting his time. Then the cries grew dimmer, faded, disappeared. He opened his eyes, and a boy was standing looking at him. The boy said, ‘It doesn’t matter, you know.’ And he said. ‘What?’ And the boy said, ‘We always made the best of it. We always will.’ Then the Poet said, ‘But, tell me, one thing, did anyone bother asking you?’ The boy just laughed.

The Poet felt angry, that others didn’t seem to care about something he thought more important than anything. The chance to run, forever, towards the sun, the horizon, a limitless future. He thought, looked up, but the boy had gone. As everything did, he guessed, in time (as the PA seemed to whisper, ‘Swing your partner round and round, and turn your corner upside down’).

So, the State would win, but he returned home, determined to describe his final visit. Feed his yabbies, play some guitar, watch the documentary he’d taped about Apollo, and his brother, Artemis.

Stephen Orr is an Adelaide-based writer of both fiction and non-fiction. His most recent novel, The Hands, was longlisted for this year’s Miles Franklin Award. Orr recently wrote another column for InDaily about funding cuts affecting the State Library.

It was announced this year that Windsor Gardens Secondary College and Gilles Plains Primary School would be merged to create a new school to open in 2017.