Brexit’s link to the hand of history

A glance back over European history helps to understand the British psyche that led to the Brexit vote, writes Adelaide-based UK expat Dewald Behrens, arguing that Brits haven’t turned into xenophobes or lurched to the right.

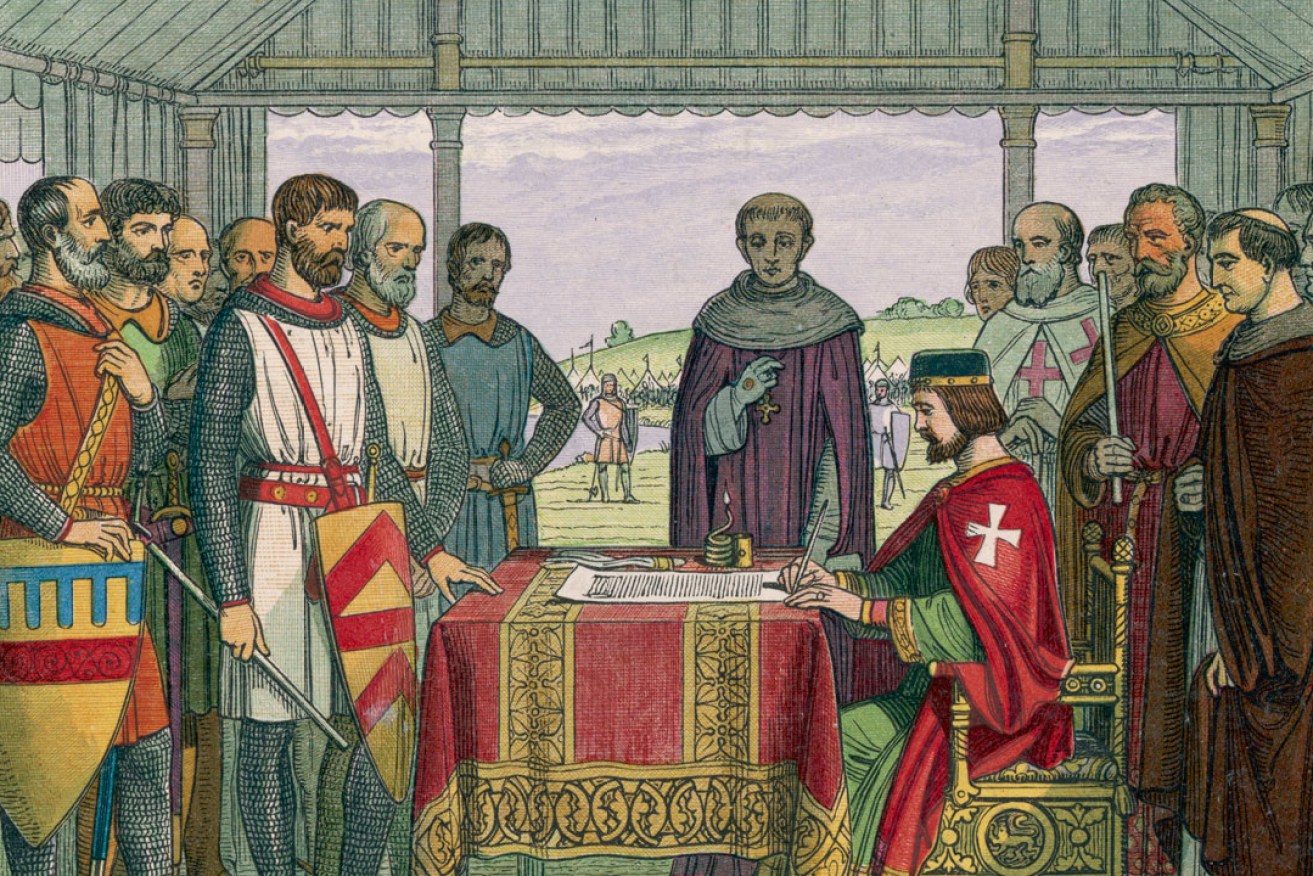

King John's signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 paved the way for an uninterrupted parliamentarian democracy. Photo: Mary Evans Picture Library

I read the critical commentary and overwhelmingly negative international reaction to the outcome of the Brexit vote with some bemusement, as there seems to be a limited understanding of the British psyche that led to this outcome. The response seems to have been guided by the shorthand of modern populism, rather than the long hand of history.

The reason for this outcome can be summed up in one word – accountability.

For a country that treasures its own civil liberties, the idea of becoming a part of a much bigger system where it forms only a piece in the puzzle of any final political outcome is too much to ask. This is especially true when the people making the decisions do not even ever need to set foot on British soil.

For instance, most people forget that Britain has not been successfully invaded since 1066, when William the Conqueror was victorious at the Battle of Hastings. Even then he was a distant relation of the incumbent King Harold, whose army was probably exhausted from winning the last major Viking invasion battle of the British Isles at Stamford Bridge, more than 300km away less than three weeks before.

Almost all the rest of Europe has been successfully invaded either during the Napoleonic Wars or the World Wars.

The British Magna Carta has become a standard in any study about law and civil liberties. It means “great charter” and was signed by King John and a group of rebellious barons in 1215, at a time when Europe was still ensconced in the feudal system. It paved the way for an ultimate uninterrupted parliamentarian democracy. In contrast, countries like Spain were still under a dictatorship until 1974 and the old eastern European bloc countries did not have their first “free” elections until 1989.

The word “parliament” was first used by the English, specifically Henry III in November 1236. In medieval times in England, Parliament was many times a mobile affair, with sittings at places like Shrewsbury, Gloucester and Berwick.

The European Parliament may have benefited from this type of process to become a bit more personally visible. For instance, Jean-Claude Juncker, the President of the European Union, has never visited the UK in his official capacity. Some may say that that would have been stepping into the lion’s den, but is that not the duty of top politicians – to plead their case in the face of adversity? Australia’s political leaders did not shy away from marginal or opposition-held seats in the lead-up to this month’s federal election.

So it is unfortunate that the outcome of the Brexit vote is seen as an Anti-European vote. The stark extremes of the question of remaining as a member of the European Union or leaving will, with the resultant rejection, leave many other Europeans rightfully feeling aggrieved. Although the British (and English-speaking countries in general) are generally bad at it, French, Spanish and German – in that order – are still the most popular second languages to choose to learn at school, and nine out of the 10 most popular holiday destination for the British are in Europe.

The European Community was formed in 1967. The UK was part of the second tranche to join in 1973. At the time it was more of a trade treaty with economic benefits, but this was followed by expansion and change into the European Union in 1993, adding a political and justice rule.

This development never really sat that comfortably with the British people, with UK court rulings being overruled by European courts. As a political point, within the UK, Parliament is considered supreme. However, when English law contradicts EU law, EU law prevails. This led, for instance, to the introduction of some sometimes minor, but bizarre high-profile laws, such as the banning of “abnormal curvature” in cucumbers and bananas – repealed in a vote by the majority of EU states some years later.

The general UK population tried, for years, to gently inform the political establishment of their feelings by their voting habits. In 1999 UKIP (UK Independence Party) landed its first seats in the European Parliament, with three, a total of 6.96 per cent of the vote. By 2004 they took 16.1 per cent and in 2009 they became the second biggest UK party in EP with 16.5 per cent and 13 seats. By 2014 they became the biggest UK political party in the European Parliament with 24 seats and 26.6 per cent of the vote.

At the same time, UKIP hardly made a voter impact on domestic politics, and after the last election returned only one Member for Parliament. So the British people actually sent a clear message to leaders by voting in an anti-European party to represent them in Europe, but rejecting them in domestic politics.

The reason for this, is that the ordinary UK citizen is not, for instance anti-immigration. But they are opposed to someone in Germany telling them how many they should take. Otherwise they display the same concerns that any rich country, especially one with such a gracious social policy, would have regarding immigration.

They have not turned into xenophobes or lurched to the right – they just elected a Muslim mayor to their capital city, the first European capital city to do so. The percentage of foreign-born immigrants in the UK is higher than that of Germany or France, based on 2014 statistics. A very healthy number of UK expats live in other European countries, especially France and Spain, while there are a thriving number of other European expats in the UK. This will not change.

So as Hugh Laurie (of House and Blackadder fame) so accurately said: “They’re very harsh people, the British, hard to impress, very tough on each other, but I rather like that. It’s not that they are more honest – you’re just under no illusion with them.”

UK citizens were under no illusion they made a tough decision. But they are quietly resilient and tend to sensibly steady the ship. Already it seems most certain that the most likely successor for the prime minister will actually be a steady negotiator who originally wanted to remain in the EU.

It will take longer to rebalance and build trustworthy relations with their European counterparts, and to keep and find new international trading grounds to keep the UK as a central economic hub.

But it will be worth it, because it stays true to the spirit of June 15, 1215, at the rather obscure meadow of Runnymede where a medieval manuscript was signed enshrining individual rights. Even though the original Magna Carta could not avert war – and this Brexit may yet have its own storms – three of the original clauses are still part of current British law.

At ultimate stake here is civil liberties, and the British know they have a tough fight. But they are, with the friendly wink of experiences past, steadfast to prevail.

Dr Dewald Behrens is a senior specialist in emergency medicine in Adelaide with a keen interest in history. He is a UK citizen but did not vote in the Brexit referendum.