Why capping Adelaide’s urban sprawl is good for everyone

Contrary to political and industry criticism, limiting Adelaide’s urban sprawl will be good for the city and for jobs, argues planner George Giannakodakis.

Photo: Nat Rogers/InDaily

The recent political push back on the need for urban growth management, by housing and building lobby groups and the US-based and self-styled think tank Demographia is surprising on many levels. But this has not been as surprising as the lack of political bipartisanship on the policy, given that it was a State Liberal Urban Planning Minister, Diana Laidlaw, who first pushed for greater urban density in the inner city, a limit on urban sprawl through imposition of a boundary, and population growth in the city.

The 1999 ‘Green Paper’ called for increasing housing choice by continuing to encourage infill and redevelopment in middle ring suburbs (Mawson Lakes to Marion) or urban regeneration and protecting areas set aside for future housing and industrial development and prime agricultural land. At that time it was an increasingly difficult task given that greenfield development represented the majority share of all new housing.

Shifting demand for housing

Putting ideological views aside, information and analysis is critical in community debate. Unfortunately it has been conspicuously absent in relation to the proposed state planning reforms. The proposed ‘Environmental Food and Protection Zones’ would do as the name suggests, but for the sake of urban growth management is referred to herein as an Urban Growth Boundary.

In contrast to the early 2000’s the conditions for a boundary have changed. A phenomena across all Australian cities, including Adelaide, is that demand has shifted to the middle ring suburbs reflecting people’s changing living preferences, and younger generations choosing to live in middle and inner ring locations, closer to main streets and good public transport.

Infill now represents up to 80% of all development in some Australian cities. In Adelaide there is currently enough zoned or deferred urban land within the boundary to cater for 25-35 years of greenfield growth (at current rates); between 55-70 years of higher density housing capacity in the city; and up to 90 years of infill housing capacity in the middle ring suburbs, even after preserving character and historic residential areas. Therefore, it is highly unlikely an Urban Growth Boundary would trigger a spike in house and land prices.

Are taxpayers willing to subsidise house and land packages on the fringe at around $90 million per thousand homes?

There is a view now that rising house prices (across all Australian cities) over the past decade have had a lot more to do with the policy and financial and institutional levers that fuel demand. This includes the availability of mortgage finance, low interest rates, first home buyers grants and breaks (several in the last two decades), rising household incomes and wealth, employment, household formation and investment. The huge disparity in house price rises across states has been irrespective of the vastly differently levels of land supply by city, where house and land package costs are relatively close.

The housing crisis seen in Melbourne and Sydney, but not Adelaide, has been triggered by a lack of ready zoned housing opportunities to quench the market thirst for urban infill in middle ring and inner city locations. Adelaide is fortunate to have the cheapest middle ring suburbs of the mainland state capitals. House price rises have had nothing to do with a lack of land supply in greenfield areas, but have had a lot more to do with demand drivers such as low interest rates.

Low density is expensive

By global city standards, metropolitan Adelaide has one of the lowest average densities at 1,100 people per square km. Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, who have densities up to 7,000 people per square km living primarily around the city, tram and train corridors, Adelaide’s suburban areas peak at 3,000 people per square km (km2) (e.g. Unley and Norwood). Adelaide’s population is spread out thinly across nearly 90km of metropolitan area (more than Melbourne which has over three times the population), which adds about $200,000 to household running costs over a 20 year period.

Consequently, Adelaide also has the lowest public transport cost recovery ratio of all state capital cities, at 21% (this is the amount the Government recovers at the fare box from running bus, train and tram services). In other words, taxpayers have to subsidise the other 79% of running costs to the tune of about $200m per annum, a result of the lower densities and therefore fewer patrons. In Melbourne, density brings with it vibrant main streets and neighbourhoods full of people at all hours of the day, greater local economies, increased cycling and walking journeys, healthy public transport use and less reliance on the motor car.

Low population density means diminishing catchments for retail and commercial property investors and owners, which is a concern given Adelaide’s current high office vacancy rate in the city at above 14%. Greater Adelaide’s annual population increase, although relatively higher than it has been for decades, is a mere 14,000 people per annum, which is as much as some Melbourne local government areas grow in a year.

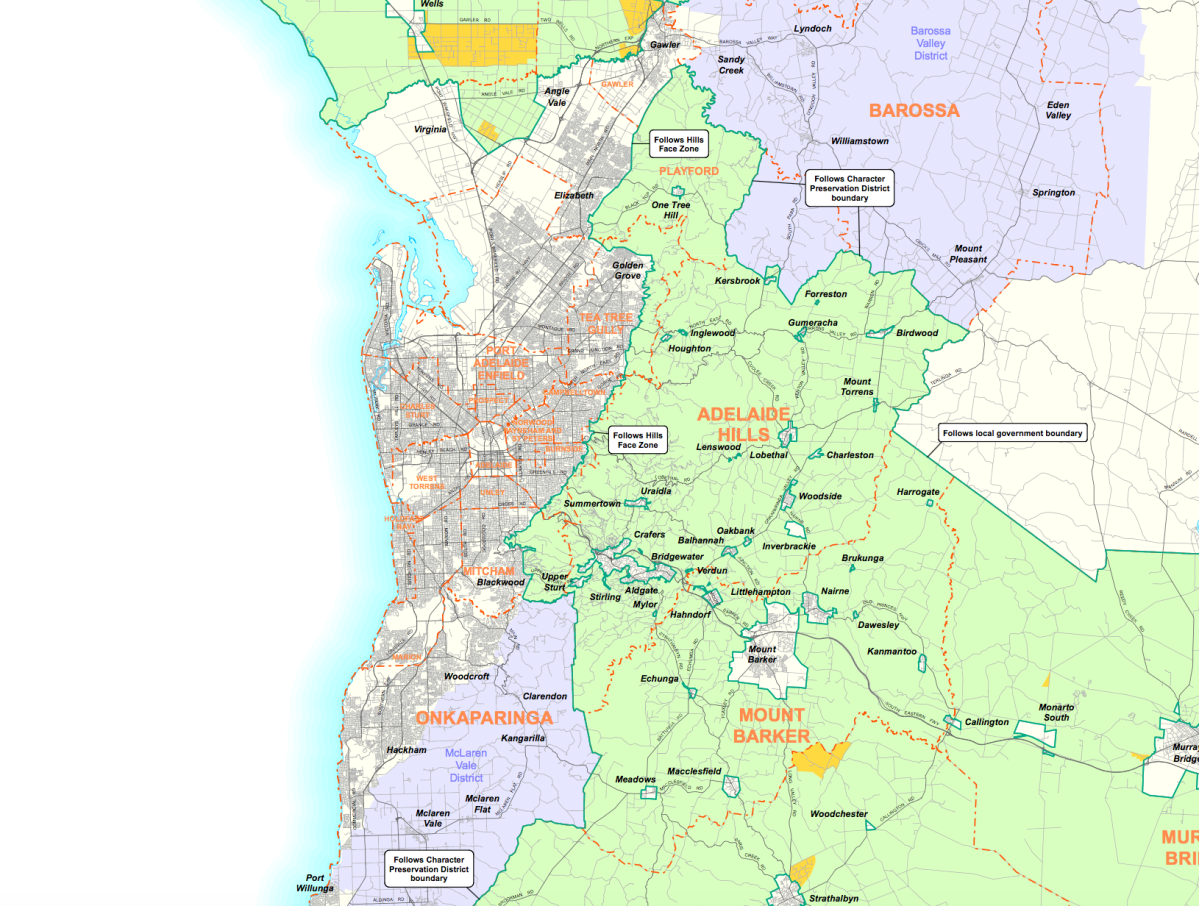

Detail from a map of John Rau’s proposed urban growth boundary. The purple areas are already covered by “character preservation” legislation, which restricts urban development, while the green areas are designated as “environment and food production” areas.

Infill creates more jobs than greenfields

The subjective notion that an urban growth boundary would limit housing choice has been raised several times.

There are at least 15 different infill development types catering for various sized blocks and backyards, demographics, family size and composition, as well as densities ranging from 24 to 460 dwellings per hectare.

One might question the recent view that not providing enough housing on a traditional quarter acre block “is a serious attack on our way of life”. It could be argued that this may be exaggerating this market niche and there will, in fact, be enough vacant ‘McMansions’ to cater for that future demand as baby boomers and empty nesters downsize and move closer toward the city centre.

The view that an Urban Growth Boundary might erode building industry jobs is also surprising. InfraPlan’s 2013 analysis of urban infill versus greenfield development showed that, when comparing developments types per 1000 net dwellings, infill creates 4,800 more jobs; provides a $375m greater return to the state economy and contributes $200m more in wages and income to the building sector including tradesmen.

Suburban town centres and main streets are in desperate need of people, which equals more visitors and happy and secure tenants, translating into healthy property yields.

To simplify this, while you would need to build 1,000 new houses on greenfield sites to cater for 1,000 new families, you would need to build 2,000 homes in infill areas to achieve the same net outcome. This comprises 1,000 dwellings for the new families and 1,000 to replace the housing removed for those who lived there (or relocated from elsewhere). That’s at least a doubling of the building turnover.

Given Adelaide’s relatively low building turnover of 8,000 new dwellings per annum, a builder or building tradesman might consider supporting a policy option that doubles metropolitan-wide building turnover. In the case of Adelaide, it might be infill development accelerated by an urban boundary.

Profit margins are similar for most house builds irrespective of the development margins on that land. House and land packages located in our middle ring suburbs are relatively cheap compared to other cities and almost the same cost as on the fringe; yet they create around 2.5 times more building industry jobs and state economic benefits.

Furthermore, our understanding and interpretation of the term ‘family’, as well as other social norms have become more complex and evolved from a traditional structure, one that perhaps suited McMansion style dwellings and associated lifestyles at a particular point in time. This social diversification along with technological advancements in communications, transport, retail, finance, personal management, as well as the way we work (electronically and logistically) have facilitated shifts in our lifestyles, resulting in:

- the consolidation, re-prioritisation and continual reduction in size of possessions (e.g. smartphones, computers, electronic data storage etc.);

- moving toward varied and shared economies (e.g. car/bike share, communal Wi-Fi, community gardens, increased importance on local spending and ‘market’ style retail etc.); and

- a society abundant with choices.

The contemporary diversity of lifestyles warrants consideration within this discussion, as well as an equally varied selection of dwellings to cater to a variety of demographic groups.

Urban sprawl and the infrastructure crisis

Finally, levies and the cost of infrastructure on new housing considered to be unfair is an interesting topic. Melbourne based SGS Economics and Planning principal Marcus Spiller says “Australia is lacking in terms of systems by which local and state governments are able to raise capital for new infrastructure to service greenfield sites”. He continues by saying “developer contributions in Melbourne are generally small and there is little in the way of value capture mechanisms in place to capture part of the uplift in property values which new infrastructure creates in order to help fund the infrastructure in question”.

InfraPlan’s own planning and infrastructure work for Melbourne local governments in greenfield locations has uncovered a serious backlog in needed social and physical infrastructure (e.g. schools, healthcare, roads, trams and trains), now counted in the tens of billions of dollars. A crisis is brewing where worker productivity levels are now falling (recent ABS data on Gross State Product per Capita) despite Melbourne being the fastest growth centre in Australia.

In spite of the ‘liveability’ crown, which primarily reflects the lifestyle of Melbourne’s inner city residents, the social issues on the outskirts of the city are mounting. This is reflected by the need for three times the average number of police stations in some areas. Local traffic congestion is now at serious levels where close to 70% of workers are stuck in traffic jams every morning before they’ve even left their council area.

If you’re going to have growth on the fringe, someone needs to pay for infrastructure, which is around three times more expensive than infill locations given that inner city and middle ring suburbs have some existing capacity. So, if it’s not the development industry, the question then becomes who? Are taxpayers willing to subsidise house and land packages on the fringe at around $90 million per thousand homes? Are infrastructure bonds the answer?

InfraPlan’s modelling shows that if urban growth management were used to redirect peripheral greenfields to infill development the following benefits would result:

| Assume 20,000 dwellings can be redirected from greenfield to infill development1 over 30 years |

Benefits |

Net Present Value, 4% discount rate |

|

Property industry jobs |

97,000 jobs | NA |

|

Return to state economy in labour and capital |

$7.6 billion |

$4.5 billion |

|

Increase in gross wages and incomes paid to building sector employees |

$4.0 billion |

$2.4 billion |

|

Infrastructure cost savings (public and private sector investment)2 |

$1.2 billion | $730 million |

1. Apartments, re-subdivisions, minor infill, major infill etc.,

2. Assuming median costs for infill versus greenfield development

A population of more than 2 million without sprawl

InfraPlan has calculated that even at modest density levels, at about the same as Unley or Norwood (3,000 people/km2), Adelaide could fit up to 2.1 million people on its current urban footprint, which according to population projections, would supply enough land for more than 50 years of growth (that’s without relying on suburban apartment blocks while preserving character areas). Local councils, like the City of Tea Tree Gully, are falling in population and the viability of centres are waning.

Greenfields development as part of township expansions or on large tracts of reclaimed land should not be discounted from these arguments. Indeed, some townships, such as Gawler offer internal social and physical infrastructure capacity that can support a level of urban expansion without a significant impact on budgets; offer affordable house and land packages at a mixture of densities and can contribute to revitalising town centres.

Suburban town centres and main streets are in desperate need of people, which equals more visitors and happy and secure tenants, translating into healthy property yields. Indeed, given falling retail market share and office turnover it’s surprising the property industry hasn’t lobbied for an even further tightening of the urban growth boundary to increase densities in these middle ring and inner city locations far sooner.

Urban growth management is also vital for driving public transport patronage and therefore an increasingly viable public transport system that would be a sensible investment option for tax payer funds to improve reliability, frequency and comfort. While public transport projects like the O-Bahn extension are important in connecting centres such as Modbury to the Adelaide city centre (in the same vain as Parramatta to Sydney), we need more investment in public transport, such as light rail and trams, to kick start the local economy and drive property uplift, similar to vibrant inner Melbourne.

Adelaide has an estimated 90 years’ of infill supply within John Rau’s proposed urban growth boundary.

Within the proposed ‘Environmental Food and Protection Zone’ Adelaide currently has around 90 years of infill capacity, which is sufficient to around the year 2106. This is on top of nearly 60 years of apartment capacity in the city centre. If people’s preferences for middle suburban and inner city living accelerates, we estimate this would still leave at least 50-60 years of land within the boundary to cater for quarter acre living on the metropolitan fringe (including recently identified growth areas).

Therefore, it is highly unlikely that there will be a housing affordability issue or spike for that diminishing niche of the market until at least 2070.

The biggest winners from even tighter urban growth management would be the housing and building industry from more than a doubling in jobs and contribution to the economy; current property owners and investors of commercial and retail property from increased densities around centres and mains streets; a reduction of the burden on taxpayer0funded infrastructure counted in the billions over 30 years and running costs of public transport in hundreds of millions per annum.

Adelaide offers enough housing choices, not to mention the cheapest middle ring suburbs within 10km of the CBD, to meet the ever growing demand for inner city, regional centre and township living.

George Giannakodakis is the managing director of Adelaide planning firm Infraplan.

Infraplan provides engineering and planning advice to state and local governments in SA and Victoria, and the private sector including property developers.