Closing the gap between art and life

Condemned Australian drug smuggler Myuran Sukumaran stands in front of his paintings in Kerobokan prison.

What is the role of the artist in the twenty-first century? Recent months have seen artists front and centre of national and international debates about human rights, capital punishment, freedom of speech and censorship. Artists haven’t carried this much weight for some time.

It seems the aesthetic navel-gazing of the twentieth century has been eclipsed by a belief this century that art can be instrumental for society. But can art and artists really close the gap between art and life?

I am reminded of the often-quoted words of the late Robert Hughes, the Australian artist and thinker who became one of the world’s most respected voices on art. Hughes said that the basic project of art is always to make the world whole and comprehensible, to restore it to us in all its glory and its occasional nastiness, not through argument but through feeling, and then to close the gap between you and everything that is not you, and in this way pass from feeling to meaning.

Hughes went on to say that it is the work of individual artists that makes a difference, not committees or movements. But in my experience sometimes we find art and artists in the least likely places.

Father Rod Bower would not refer to himself as an artist. He’s a practising theologian but his recent work involving the broadcasting of messages, often political and witty, on billboards outside the Gosford Anglican Church in New South Wales, have more in common with art than one might think.

Bower in fact has been invited to participate in the current Fringe Festival happening – the self-proclaimed micro-nation of ‘Surrender’, devised by Adelaide-based svengalis Geoff Cobham and Ross Ganf. Bower’s billboards will provide the backdrop for the riverbank refuge and his philosophy has much in common with Hughes’ statement. As Bower says: “Surrender is all about having those important conversations … about envisioning a society where barriers are dissolved and human beings can celebrate humanity in a way that’s accessible to everyone.”

Such actions also strike a chord with the recent campaign led by Ben Quilty, one of Australia’s most celebrated artists, to save the lives of Bali Nine pair Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran who are currently on death row in Indonesia. Quilty’s actions, supported by a legion of other prominent Australians, have mobilised a mass act of mercy and compassion. Placards, posters, candle-light vigils and billboards (including Father Rod Bower’s church-side sign) have been emblazoned the nation over with the words I stand for mercy. Quilty first visited Sukumaran in Kerobokan Prison in 2012, and has since then mentored the emerging artist, witnessing at first hand the redemptive and transformative power of art.

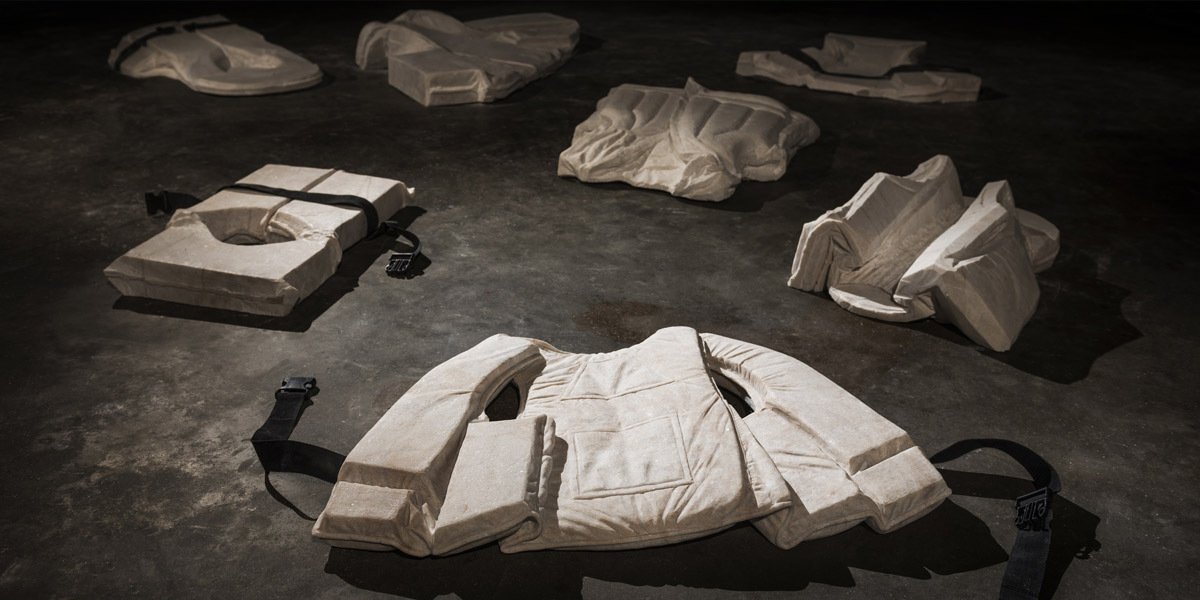

Recent work by Alex Seton, including a constellation of 28 carved marble life-jackets strewn across the gallery floor carrying the title ‘Someone died trying to have a life like mine’, prove that art has the capacity to cut through partisan politics and close the gap between art and life. Seton’s work, now on display in the Art Gallery of South Australia, was motivated by the discovery of 28 life-jackets washed up on a Cocos Islands beach in May 2013 by the Australian Federal Police.

Artists have long been part of a Humanist tradition – think for a moment of Francisco Goya and his Disasters of War, Picasso’s Guernica or even Adelaide-based artist and recipient of W. Eugene Smith award in Humanistic Photography, Trent Parke. But this instrumental turn suggests that the power of art, and change, belongs to us all.

Nick Mitzevich is director of the Art Gallery of South Australia.

He is a regular contributor to InDaily.