Philip White’s a day late, but he makes a surprise Australia Day Award nevertheless.

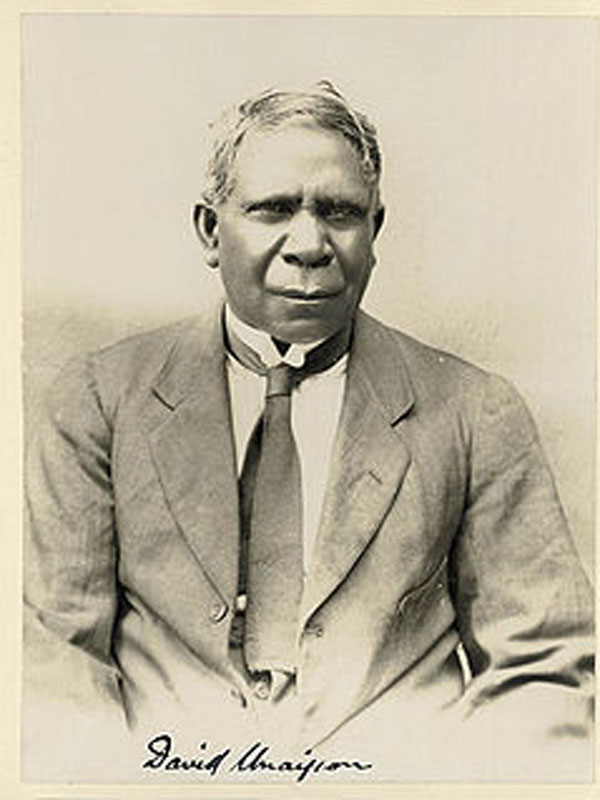

David ‘Unaipon’ Ngunaitponi was 13 when the benevolent politicians, graziers and winemakers, Charles Burney Young and his son Harry Dove Young, employed him as a servant in 1885 and built him lodgings at their Kanmantoo Pastoral Company homestead, ‘Holmesdale’. The Ngarrindjeri lad always fascinated the young Harry, pestering him with ingenious toys and musical instruments he’d made on his traditional country on the Murray Estuary at Point McLeay.

The Youngs were a racy lot. Charles Burney had married Nora Creina, daughter of Lady Charlotte Bacon, the ‘Ianthe’ in Lord Byron’s poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage – it was commonly rumoured Byron was Charles Burney’s illegitimate father-in-law. Harry Dove bore a striking resemblance to Byron.

Having studied the mathematics of surveying, Charles Burney cut himself out a lovely slice of land that extended from the dairy cattle country on the eastern slopes of Mount Barker to the lower beef and sheep-grazing rain-shadow country on the Bremer River, five miles further east. A rakish dance-hall man, Charles spent much of his time at business and pleasure in the city [read Adelaide Club], leaving Harry Dove to run the farm and winery and the thoroughbred stud at Kanmantoo.

A mad horseman, Harry Dove was a founder of the Oakbank Steeplechase. They still run a hurdles race there each Easter in his name, which is proudly cut into the redgum lintel of the stables at Johnston’s big homestead overlooking the Oakbank Racecourse. I imagine Harry Dove standing in his stirrups as he carved that graffito out with his pocket knife, wagering old man Johnston that his idea was a winner. All he needed was Johnno’s paddock, some well-horsed rivals, and somebody to make a book.

The original Kanmantoo vineyard was 25 hectares of Cabernet Sauvignon, Shiraz, Grenache, Malbec and Mataro – more or less the ingredients of the better Bordeaux reds of the day. Through his mate Sir Samuel Davenport, Charles Burney had engaged the services of the genius French winemaker Edmund Mazure, who there perfected his recipe for the wine style he would later call St Henri Claret at Romalo.

Mazure’s Kanmantoo Vineyard St George Claret was fermented cool using a water-driven heat exchanger they invented, then blended and stored in seasoned 500-gallon oval oaks for six years before bottling.

Those oaks are full of wheat these days.

At the Exposition Universelle, the Paris World’s Fair of May to October 1889, held to coincide with the official opening of the Eiffel Tower, St George Kanmantoo Claret won the top gold medal. I’ve held the damn thing in my hands. It’s as broad as a saucer, and very heavy. These days they give you a piece of paper that comes out of some Troy or Jacinta’s desktop printer in Kent Town or somewhere.

The wine critic from The Register, Ernest Whitington, gave a priceless account of drinking these world-leading wines when he visited ‘Holmesdale’ with another newspaper bloke in 1903. Harry Dove had met them in a city pub at 4pm. The rain “came down in torrents” as they drove through the Mount Lofty Tiers – “where cattle duffing was rife in the early days” – took fresh horses at Crafers, and were at table at Kanmantoo by 8pm.

“We sat around the open fireplace, with its great blazing logs,” Whitington reported, “And talked about the wine industry …

“By the way, at dinner there were two clarets on the table, white seal French, and St George 1897 vintage. The visitors picked out the Kanmantoo article as the French wine. But that is not to be wondered at, because a claret from these cellars took the gold medal at the Paris Exposition against the whole world. As Mr Young put it, he awoke one morning to read in The Register that his wine had taken the coveted prize, and was, indeed, famous.”

From his single-room studio at the back of ‘Holmesdale’, Unaipon would ride to the Callington Railway Station to catch a train to the city, where under Charles Burney’s encouragement at the big house in Walkerville, he studied anthropology, science, literature and music. Publicly a teetotaller, Unaipon nevertheless worked many vintages in the Kanmantoo cellars – his signature is in the cellarhands’ paybooks; it appears by the names listed there that the harvest was picked (into kerosene tins) by other Ngarrindjeri people under his supervision. The bookwork shows he was hands-on.

For a man of his genius, winemaking would have been a cinch for Unaipon.

I have a romantic notion of the polite and eager 13-year-old lad there in the cellars with a candle, assisting Mazure, Charles Burney and Harry Dove prepare and bottle the St George Claret samples to be sent off to the big Paris show.

They must have been heady days: Unaipon was a tireless inventor; an Antipodean Da Vinci. In the ‘Holmesdale’ shearing shed where I worked as a kid, he devised a method of converting rotating flywheel and belt-type motion to sideways lineal, and so invented the shearing handpiece, which put Australia on the sheep’s back and got him on the $50 bill, although I don’t think he ever made a cent from it.

They must have been heady days: Unaipon was a tireless inventor; an Antipodean Da Vinci. In the ‘Holmesdale’ shearing shed where I worked as a kid, he devised a method of converting rotating flywheel and belt-type motion to sideways lineal, and so invented the shearing handpiece, which put Australia on the sheep’s back and got him on the $50 bill, although I don’t think he ever made a cent from it.

He constantly experimented with boomerang shapes and flight, and in the late 1800s decided that if two boomerangs could be attached at right angles to a driven spigot, cargo could be lifted and transported. In other words, the helicopter. His direction converter in the shearing handpiece could make the prop blades adjustable for lift.

It wasn’t until 1936 that Focke-Wulf built the first working chopper, by which time the old vines at Kanmantoo had been uprooted and Harry Dove Young, MLA, was no longer well. Combined with the harsh local Tapanappa schist, eutypa ‘die-back’ or ‘dead-arm’ had gradually chewed away at the dry-grown vines until the yields were down to half a ton to the acre. The vines were, after all, nearly a century old.

Good quality, sure, but there’s no money in that.

Harry Dove married Anna Theresa Moore; they had one child, Nora. Harry Dove died in 1944. A wiry, jockey-sized tomboy, Nora was famous for tearing about on her dad’s Ferrari-class thoroughbreds, not just bareback, but with no kit whatsoever. All she needed was a strand of mane to steer one of those big shiny bastards at full gallop.

Very early in her rebellious life, Nora went off to Paris to study law at the Sorbonne and hang out with the impressionists at the Louvre. There’s a wonderful letter to her dad in the files. Nora’s dozing off at boring lecture in Paris, gazing out the window at the Seine, and she sees a barge laden with her Dad’s St George’s Claret being hauled into town. Her Dad’s brother, Burney, just happened to run the Australian wine office in London – he was the forerunner of today’s Australian Grape and Wine Authority.

By the time I was old enough to mow her lawns in the ’60s, Nora’d moved in to manage what was then Kanmantoo Station with her Beretta-pistol-packing girlfriend, Ida Tate Smith. The eccentric kleptomaniac Alison Woosterman Howgate lived in a stylish modern cottage on their large lawns.

Despite being an expert driver of her big V8 Valiant Regal, Alison always pretended to be blind.

On Saturdays, the expert painter Nora would run watercolour classes on the verandah while I mowed the lawn. I couldn’t imagine then why you’d have a kid mow the bloody lawn with a noisy, smelly old Victa four-stroke while you were sitting there hitting the Chestnut Teal sherry and learning how to paint, but I imagine it had something to do with proving one was sufficiently well orf to run staff: the internals of the big house were managed by Miss Margaret Dadow, who similarly lived alone nearby on the farm.

They were mainly khaki-jodhpur short-back-and-sides lasses at those genteel soirées. Not a sherry head, Nora would stir heaps of brown sugar into dark rum in a huge grandpa’s tea cup and lap it noisily with a teaspoon. She chain-smoked Alpine filters and spoke with a brilliant Tom Waits timbre. It was a cool but crazy place to live, Kanmantoo in the ’50s and ’60s: there weren’t many farming villages anywhere else whose aristocracy was an openly gay matriarchy.

Nora and Tate would climb into their best tweeds now and then, wash the Borgward Isabella, and drive to Tailem Bend or Murray Bridge to visit Unaipon in the old folks’ home. They revered him. He died in 1967, when I was 15 and still playing cowboys and indians around the old winery. He was obsessed with unlocking the secret of perpetual motion, right till the end.

A courteous, conservative man, Unaipon wasn’t impressed when more activist blackfullas instigated the Day of Mourning to celebrate the 150th arrival of the First Fleet, so he’ll probably be pissed off by my nomination of him to my Winemaker of the Year on Australia Day 2015.

And, dammit David, I’m always gonna call it the Original Australians’ Day from now on.

If only I had that champion St George Claret I’d chink some proper crystal in your honour. In the meantime, there: I’ve outed you. You were a winemaker.