What’s cranking up the heat this week?

A 2012 image of a tropical cyclone moving towards the Pilbara and Kimberley coasts of Western Australia.

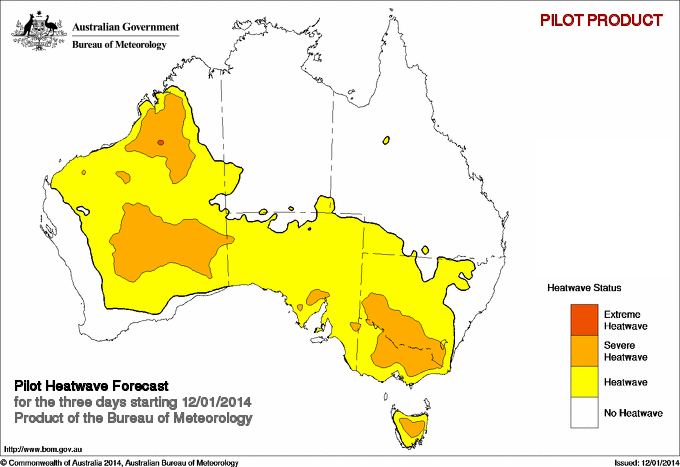

Across south-eastern Australia this morning, people woke up to forecasts of scorching heat for the week ahead. Players and spectators heading to the Australian Open should prepare for some baking hot days at the tennis: 35°C today, rising to 41°C on Tuesday, with temperatures in the high 30s or low 40s expected to linger until the weekend.

Coming after a relatively mild summer weekend, many of us will be wondering why it’s got so hot, so quickly.

That was the question my colleagues and I asked ourselves a year ago, when we began looking at the causes of severe heat waves. In particular, we wanted to know what made the 2009 summer heat wave – which set new records for the most days above 40°C in many parts of south-eastern Australia, and which killed hundreds of people – quite so deadly. Were there any hidden culprits behind the record-breaking spell of fierce heat?

What we discovered was that a seemingly unrelated tropical cyclone off the Western Australian coast contributed to making the south-eastern Australian heat wave worse.

And what’s about to happen with this week’s heat is a textbook example of what we found.

Watching wild weather in the west

This week, a tropical low is forecast to intensify over northern Western Australia, and a trough will extend from north-west to south-east across the state. Whether or not a tropical cyclone develops, the effects of these low pressure systems will be felt as far away as Melbourne and Hobart.

Our recent research in the internationally peer-reviewed journal Geophysical Research Letters explains how tropical lows and tropical cyclones affect heat waves in south-eastern Australia.

In late January 2009, Tropical Cyclone Dominic hit the Western Australian coastline, causing minor structural damage and bringing down power lines in the small Pilbara town of Onslow. Flooding of a nearby river resulted in significant crop damage, and caused a train to derail near Kalgoorlie.

But as cyclones go, Dominic wasn’t so bad: at its peak, the cyclone only reached category 2 status, well below the most severe category 5 level.

Yet as our research showed, even at that level, the cyclone over in Western Australia still had powerful downstream effects for the extreme heat wave across South Australia, southern New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania in late January and into early February 2009.

Read more: Cyclone’s SA visit deepest since 1907

During this heat wave, Ambulance Victoria was swamped with a record number of emergency calls, while the Adelaide morgue ran out of room.

Later, the Victorian Department of Health estimated that 374 “excess deaths” occurred in the week of January 26 to February 1 2009. Although it is not possible to directly attribute mortality solely to the heat wave, there was a clear spike above the normal death rate, highlighting the health risks of heat waves, particularly for elderly people.

So how did Tropical Cyclone Dominic increase the intensity of that heat wave? And how do tropical lows in Australia’s west – like the one we’re seeing again this week – affect the weather as far away as south-eastern Australia?

When the pressure’s on

It turns out that the position of the tropical cyclone, rather than its size or severity, is what really makes a difference.

It doesn’t even need to be a full-blown cyclone; as we’re currently seeing, even a tropical low can have a big impact on south-eastern Australia’s weather.

Heat waves in Victoria are associated with slow-moving high pressure systems, or anticyclones. These surface highs hang around over the Tasman Sea for several days, bringing hot northerly winds from the interior of the continent.

During heat waves in Victoria, there is also a similar anticyclone at higher levels in the atmosphere.

These upper level anticyclones form when very long, planetary-scale waves in the atmosphere (known as Rossby waves) break to the south of Australia.

Our recent research showed for the first time in Australia how those upper level anticyclones have been present in all of the most severe heat waves in Victoria over the past two decades.

How cyclones work

The circulation around tropical cyclones at low levels is cyclonic, as air spirals in a clockwise direction (in the Southern Hemisphere; it spirals the other way in the Northern Hemisphere) into the centre of the storm where the pressure is lowest.

At upper levels, the air flows out again from the centre, and its nature changes to anticyclonic, switching to rotate in an anti-clockwise direction.

This outflowing air can intensify heat waves over Victoria in two ways. The first is when the outflow “nudges” the upper level jet stream, the band of strong westerly winds that circle the globe at mid-latitudes in both hemispheres.

When the outflowing air from the tropical cyclone nudges the jet stream south of western Australia, the disturbance generates more waves. This results in a stronger upper level anticyclone over Victoria.

The second way in which the intensification can occur is a direct result of the anticyclonic properties of the outflowing air. The outflowing air can be carried by the winds directly into the upper level anticyclone over Victoria.

The more intense the upper level anticyclone over Victoria, the more persistent it will be. This makes it more likely that a heat wave will form as higher temperatures continue for several days.

You can imagine this as being a bit like putting a pebble into a stream. The larger the pebble, the harder it will be for the water to shift it, and the more likely it is that the pebble will remain in place for a while as the water flows around it.

The cyclone effectively makes the pebble that is the anticyclone a little bit bigger, so that it stays stationary for longer.

Our improved understanding of how heat waves form should help weather forecasters better predict when extreme heat waves will hit south-eastern Australia.

It will also help in studies of how the intensity and duration of heat waves might change in the future due to climate change.

Tess Parker is PhD candidate at Monash University.

This article was first published at The Conversation.