50 years on, a dream partially realised

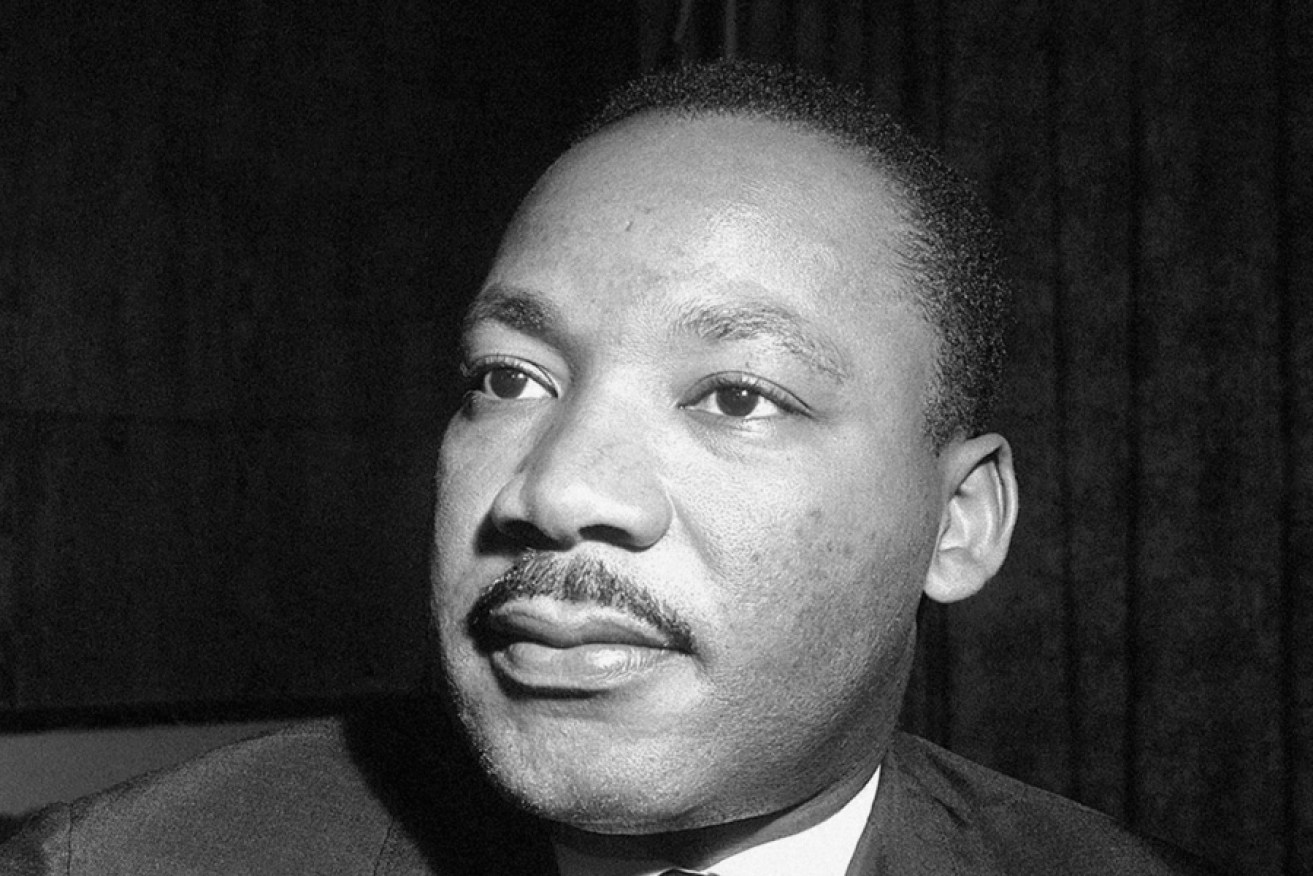

Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr delivered his "I have a dream" speech.

It was the most terrifying image I had ever seen – an image that haunted me throughout my childhood.

I must have been about 10 years old, maybe younger, and I was flipping through the volumes of a new children’s encyclopedia.

At first I experienced it as visual dissonance: was I looking at a ghost, a costume party, a cartoon, a strange uniform?

In fact, it was the latter: members of a group that I learned was called the Ku Klux Klan, gathered around a burning crucifix in their grotesque disguises.

The dispassionate text described the Klan and its activities: how they hated Jews and black people; how they murdered, bombed, bashed and burned their enemies.

Until that moment, I had no real understanding of bigotry at its most poisonous and expressive.

I had a vague notion of the Holocaust, but no real grasp that it was an attempt to wipe out a specific group of people.

These Klan members, in their white quasi-religious robes and peaked masks, seemed uniquely and specifically terrifying, particularly as my younger brother played nearby, his skin a dark chocolate brown.

Would they come for him? I imagined the Klansmen gathered on our front lawn, planting a burning cross in the thin kikuyu.

This was a new and uniquely cold feeling. People might hate my brother simply because of the colour of his skin? It made little sense.

In the many years since, I’ve realised that racism is a lot less exotic than the white-cloaked Klansmen – a lot more ordinary and everyday. Toxic, yes, but essentially mundane. Commonplace, even.

Its causes include simple learned behaviour, misconceptions, generic fear of the unknown, and isolated experiences between individuals, as well as more complex and sinister machinations, such as the centuries-old cultural norms that once led Europeans to believe that Africans were not human – so animal-like, in fact, that they could be herded and shipped off as slaves to the American colonies, without any moral qualms.

Those bigger forces were the same that caused our nation’s colonial forebears to declare this continent terra nullius. Aboriginal people were not considered properly human, a fact borne out by our nation’s constitution which, until 1967, implicitly classified the indigenous inhabitants along with the flora and fauna.

It is the weight of this history, centuries of fear and pain, that is brought to bear on a pressurized pinpoint when someone today calls someone else a name which dehumanizes them.

It is the weight of this history that made footballer Adam Goodes – a big, strong, accomplished, mature man – feel like a hurt teenager when a young girl called him an “ape”, and then devastation when broadcaster and Collingwood president Eddie McGuire made his unfortunate “King Kong” contribution.

Responses since these incidents occurred show a level of confusion, perhaps even fear, in the community.

Maybe we need to stop presuming that real racists are only the people in white cloaks carrying flaming crucifixes.

Some – like those who believe this is all “political correctness” – just want the issue to go away.

This is a powerful stream of thought in Australian life.

We like to downplay the idea that there is widespread racism in this country.

We don’t like to examine too closely the ideas of race that played a role in settlement and federation.

Because, we reason, isn’t being accused of racism a terrible thing? Like being accused of being a serial killer?

But this extreme stigma connected to racism is not helping to solve the problem.

It does nothing to solve the deep, real problem of racism, to pretend it is an exotic or unusual trait in a person.

It’s not surprising, then, that what we often try to do is argue that the real cause of any upset is the thinness of the skin of those who are subjected to racism; as if the racial abuse is a generic form of name-calling, akin to teasing someone for being overweight.

It’s not. The entire 20th century tells us that bigotry based on race, ethnicity or religion is especially dangerous and contagious. The past 150 years have been a high watermark for genocide, with the deep-seated fear of difference leading to race-based slaughters on just about every continent on earth.

Ironically, the monstrous nature of these crimes can stop us talking about it, stop us talking to each other, and stop us examining our own assumptions and fears, a counter-productive dynamic exposed 50 years ago by the man who perhaps did more to combat racism than any other – Martin Luther King Jr.

The American civil rights hero, in his famous letter from Birmingham prison, reasoned that those who confronted racism were not the creators of tension in society.

“We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive,” he said. “We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.”

It is an irony that in Australian politics today, comments of this kind – or even those remotely touching on the real problem of racism – would lead to the speaker being accused of playing “the race card” – which only serves to tell me that there is more to be brought to the surface; much more than just insults thrown at footballers.

We have complicated problems yet to be solved in Australia, not least of which is the terrible toll of sickness and poverty in many Aboriginal communities.

These problems require sophisticated solutions, and I can’t help but wonder if the everyday racism still prevalent in our country remains a threshold problem with which we refuse to deal openly and honestly, a problem that holds us back from confronting both the challenges and the possibilities before us.

Maybe we need to stop presuming that real racists are only the people in white cloaks carrying flaming crucifixes.

In the years since my “tree of knowledge” moment with the encyclopedia, I’ve seen and heard a lot of everyday racism – if we’re honest, we all have.

These occasions might not have the power of that first chilling moment of realisation, but they still make me sick to my stomach – sick for my family, sick for my friends, sick for my country. The challenge, and this is difficult, is to confront it – not in a bombastic, pompous way, but thoughtfully, honestly, from the heart.

I don’t always meet that challenge, but it’s the only way to create a nation where everyone can hail a taxi, rent a house, walk down the street or enter a shop or sit on a bus without the wrinkling of a nose, or the furrowing of a brow – the myriad signals that seem tiny, but sound like a gong.

King’s dream – enunciated so powerfully 50 years ago – was for his children to be judged not by the colour of their skin, but by the content of their characters.

We may have travelled part of the journey, but we’re not there yet.