Horton: How Holden shaped Adelaide

The "People trust Holden" ad campaign. Photo courtesy Holden.

In 1973 the Australian film maker, Peter Weir was making his first feature length film titled The Cars that Ate Paris.

This wasn’t a comment on French city planning. Set in a quiet Australian outback town called Paris, it’s an absurd plot that’s been described as post modern technogothic. The town comes up with an ingenious plan to booby trap passing traffic, causing accidents to fuel the town’s wreckers on which the local economy is based. Locals go to even more absurd lengths to prop up the wrecking and the carnage in a desperate descent in to nihilism. “That’s the world we live in. That’s the world of the motor car,” sighs the town’s mayor as if resigned to the cycle of death, damage and depravity.

There will be a lot of sighs in car plants all over Australia right now.

These were the 70’s. A strong car culture was rocked by the 1973 oil shocks which cast a pall over the automotive industry for the first time. This at a time when the motor vehicle industry was at its production peak. In 1970, Australia produced 475,000 motor vehicles – more than double the number produced in 2011.

On reflection, the 70’s seem to have been a turning point for auto in Australia, even if it’s taken another 40 years to arrive at a climax. The thing about ‘mega’ shifts is that we often only view them from a position of distance, and while a lot of excellent work is being done by many right now to understand what the future of car making in Australia might be, it’s a discussion based on conditions that are beyond the control of those involved. It’s a classic wicked problem wrapped up in a whole lot of historical ‘dark matter’. At times like this, it might be worth reaching for a more anthropological framework to make sense of where we’re at.

It’s a point of view that steeps you in the economics of family business and war time politics, post war urban expansion, international supply chains and the fatal moves of past generations that are all still playing out today.

If nothing else, taking a longer view of Holden’s origins and early growth might take some of the partisan heat out of today’s debate, which is running according to conditions set in train, it seems, by a decision made 90 years ago. This grand narrative also gives an insight into Adelaide’s layout, and the challenges we face in providing basic infrastructure to a city that over-reached during a period of extraordinary industrial and economic growth.

The story begins

The popular story of Holden starts in 1948 with Ben Chifley launching the first Aussie made car; the FX Holden at a plant in Melbourne.

But the origins of Holden are much more interesting and earlier than this.

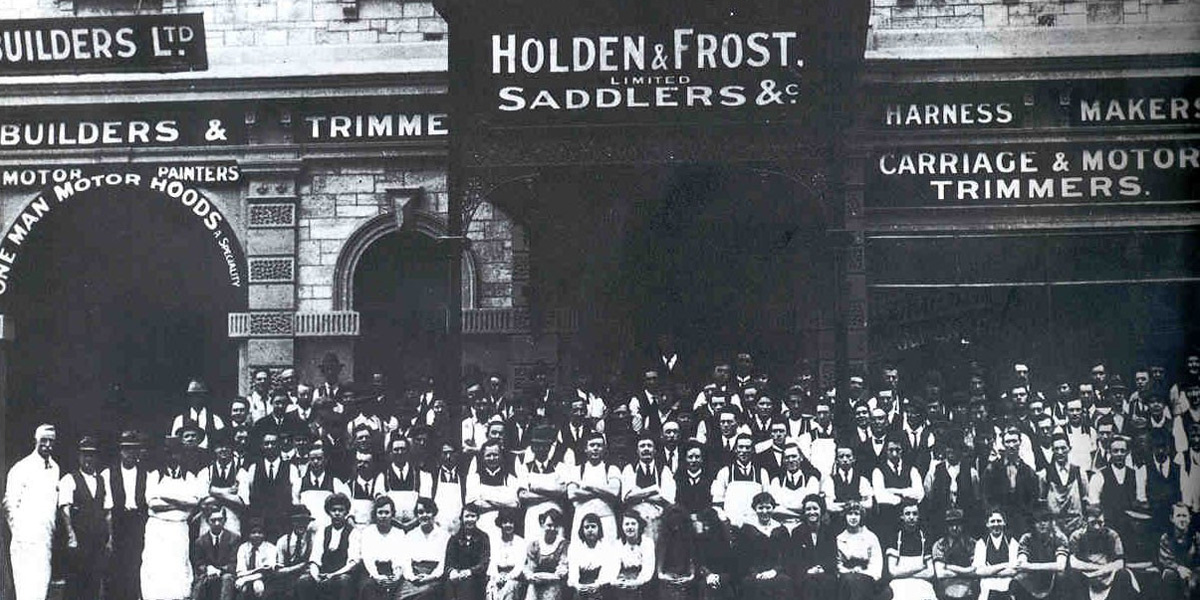

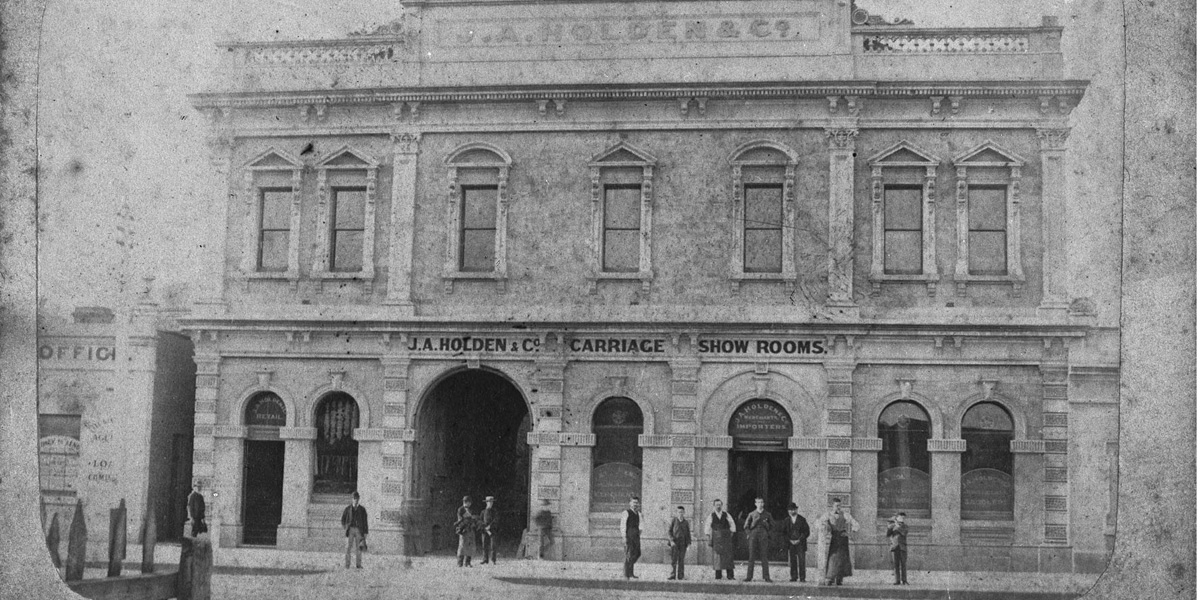

James Holden, a 28-year-old leatherworker, opened a shop in Gawler Place, Adelaide in 1858, which he expanded to include ironmongery – the skills essential for saddlery. Holden continued to diversify, merging with a carriage building company in 1885 to form Holden and Frost at a bigger plant on Grenfell Street and giving them the foundation to bid for contracts supplying defence materiel for the Boer War.

The business continued to grow over the years, with younger family members bringing with them a contemporary view of opportunities and trends, experimenting with motorbike sidecars and the first car bodies to ensure the family wasn’t outpaced by the emerging market of the motorcar.

We literally swallowed Holden in a post war master plan that wove it into the industrial and economic fabric of the place. We don’t have the option of regurgitating Holden. It’s suffused across the city’s nervous system and it’s in our blood.

Keep in mind that there was not even a mechanic in South Australia in the early 20th century, so investing in car body building was a serious case of ‘early adopting’ for a market that wasn’t yet proven, serviced or regulated.

In 1917, with First World War shipping at a premium, Edward Holden convinced the Australian government that imported chassis could be broken down and flat packed, but the space-hungry car bodies could be made in Adelaide. By 1923, Holden produced 7,000 cars in just six months. On King William St, no less. In the centre of the CBD.

But it was in 1923 that Holden’s move in to the global market set them up to both grow, and falter. Holden signed a deal with US Maker, General Motors, at first as an exclusive contract for Holden to build – on their terms – bodies for GM cars in Australia. Extraordinarily, by around 1928 Adelaide was making about 80% of Australia’s car, truck and tram bodies from two locations – Holden’s King William St plant and TJ Richards’ Hindmarsh Square workshop (TJ Richards was later bought out by Chrysler, then Mitsubishi and resulted in the development of the Tonsley plant in Adelaide’s South. Deliciously, the department now planning Tonsley’s new life is also located in…Hindmarsh Square. The more things change…)

Within a decade the Depression saw Holden bought out. And this is where the first faint whiffs of today’s issues appear. As a result of the buy-out and the tensions of the new international partnership, an outside professional replaced a member of the Holden family as General Manager. The family business became a global outfit; a company restructure reassessed the firm’s operations; decisions moved further off shore.

Holden’s Woodville motor body works in 1928. Photo courtesy History SA/South Australian Government Photographic Collection

Adelaide swallows Holden

Somewhere in the maelstrom between 1931 and 1936 a series of decisions were made that cemented GMH in South Australia, expanded Australia’s automotive capability, and triggered truly massive growth in Adelaide’s urban footprint as if to surround and swallow the organization.

In 1934 the new GMH executive resolved to restructure, close its Adelaide operations and consolidate at Fishermen’s Bend in Victoria (another site again wrapped up in GMH negotiations). SA Liberal Premier Richard Butler negotiated not just a stay of execution but an audacious plan to position GM at the centre of an integrated post war industrialisation and urban planning exercise that would span four decades, much of it driven by subsequent Premier Thomas Playford until 1965. To manage the politics, an independent review was commissioned, and a manufacturing strategy drafted (the more things change…).

This ‘build it and they will come’ strategy of Butler, then Playford was a brilliant pivot – and very likely a strategic counter move to the growing relationship between GMH’s Melbourne-focused management and the Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons.

If today’s politics is any gauge, it’s hard to believe the deal to deliver an all-Aussie car wasn’t a ‘sweetener’ and contingency plan demanded by Lyons for any possible fall out from a foreign buy out, and radical restructure in short order. It’s not hard to imagine the origins of the FX Holden may have been mostly about managing the ‘optics’ of the buy-out – even if WWII would delay the result.

So what’s the link between industrialisation and urban expansion? Butler’s decisive move was to form the South Australian Housing Trust in 1936 that would spearhead an industrialisation strategy and ensure costs of doing business remained competitive against the growing eastern states. It would achieve this by planning and delivering housing and urban growth to serve the broader industrial and economic interests of the state, still rebuilding after the Depression.

To get some idea of the scale of this expansion, the population of Adelaide’s northern plains rocketed from fewer than 8,000 to more than 68,000 people in the 12 years to 1966, the overwhelming majority of whom came here as migrants from the UK.

Holden’s story is Adelaide’s story

It’s a truism that Australian cities were designed by and for the motorcar. But it’s hard to imagine any city where this is more true than Adelaide. The growth of Holden/GMH, and its integration in to Adelaide’s urban form and its collective psyche is a perfect parallel for the growth of Adelaide itself from the 19th to the 20th and 21st century.

It shows that unpicking something so perfectly fused in the fabric of the city – it’s economy and culture – isn’t going to be straight forward. Gaining an understanding of this is not likely to be helped by knee jerk commentary on the value of “save or sink”. For Adelaide, that’s like debating whether to have running water or not. Not having an automotive industry isn’t a matter of turning something off; its infrastructure is built under and around us. It’s in our walls and under our streets.

Holden’s the same. It’s in us. We literally swallowed Holden in a post war master plan that wove it into the industrial and economic fabric of the place. We don’t have the option of regurgitating Holden. It’s suffused across the city’s nervous system and it’s in our blood.

In a physical, economic, social and psychological sense, Holden’s story is Adelaide’s story.

The task here may be less about saving car making, and more about keeping the patient stable and mobile while rehab can rewire the brain with new skills.

The anthropologist might advise that we buy the Holden brand back and start again: once again becoming small, and locally based with a rebuilding strategy based on partnering with the 21st century GM equivalents like Tesla and Tata (who’s building fibreglass cars fueled by air).

The innovator might suggest an ‘X prize’ challenge where an unnamed consortium of venture capitalists surprise us all by offering a $50m prize for a local hybrid vehicle that can retail for $10,000.

Both of these are tempting ‘wild card’ scenarios.

For all its schlock horror, The Cars that Ate Paris shows how culture is not separate from an economy but that one grows and grafts on to the other. Adelaide’s industrial economy and its culture has been built on auto making ever since those big decisions were made in the short window between recovery from the greatest depression the world had ever seen, and a war that supercharged the making of machinery, armaments and materiel.

But where reality departs from fiction is that while Weir’s film ends with some of the town’s best abandoning the mayhem under the cover of night, the actors in Adelaide’s story can’t just pack up and leave.

Tim Horton is the former South Australian Integrated Design Commissioner.