Space bling: ‘jewelled’ satellites help us to measure the Earth

Much about the true shape of our planet is known thanks to two satellites that act as targets for lasers fired from Earth.

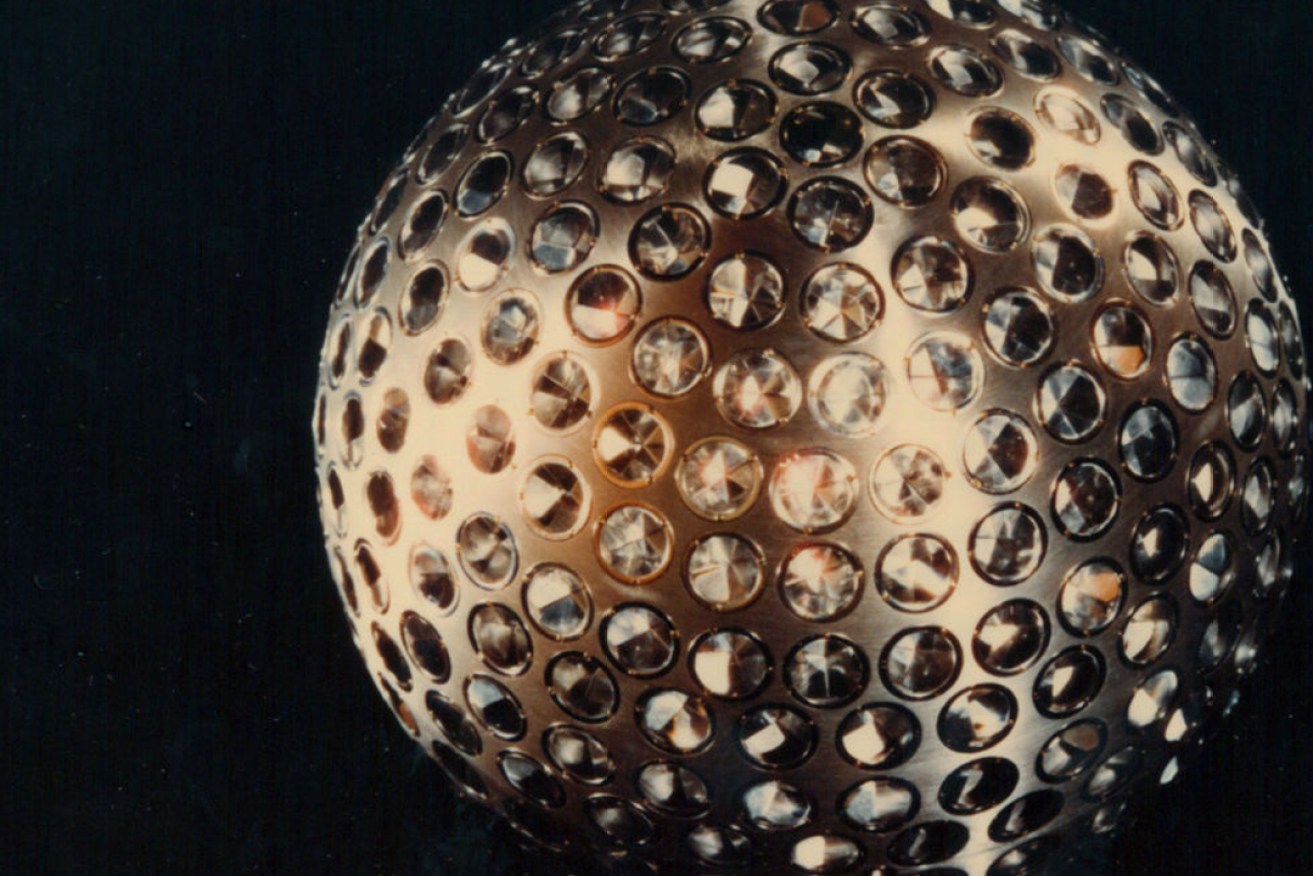

A scale model of one of the two LAGEOS satellites. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

One of them could be the most beautiful satellites ever made. In fact there are two of these jewelled spheres orbiting Earth.

And one of them carries a message for deep into the future, if there is anyone around to decipher it (but more on that later).

The ‘space bling’ twins are the LAGEOS satellites (LAGEOS stands for LAser GEOdynamic Satellite). LAGEOS-1 was launched by the United States on May 4, 1976, and LAGEOS-2, made by the Italian Space Agency, was launched in 1992.

So this year, the original 60cm sphere – its design harking back to the spherical satellites of the early space age, such as Sputnik, Vanguard and Echo – will notch up 41 years in orbit. It’s a veteran of space science.

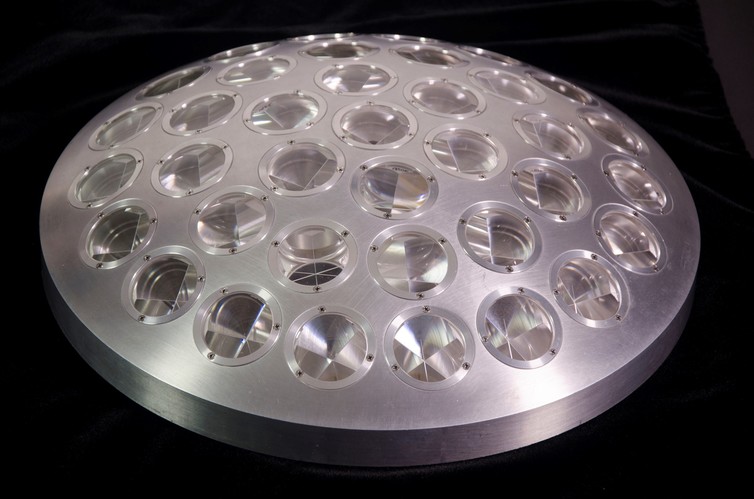

The surface of LAGEOS is dotted with 426 cube-corner prisms to reflect laser pulses transmitted from ground stations on Earth. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

The interior of each satellite is a solid brass cylinder, covered in a thick aluminium shell studded with 422 “jewels” made of fused silica, and four made from germanium.

Fused silica is made without the common ingredients of everyday glass, such as lime and soda. It has a much higher melting point and won’t crack from the extremes of temperature experienced in orbit.

This is important because the LAGEOS satellites are essentially used as inert reflectors, off which lasers can be bounced.

The two satellites travel at around 6,000km from Earth in a circular polar orbit.

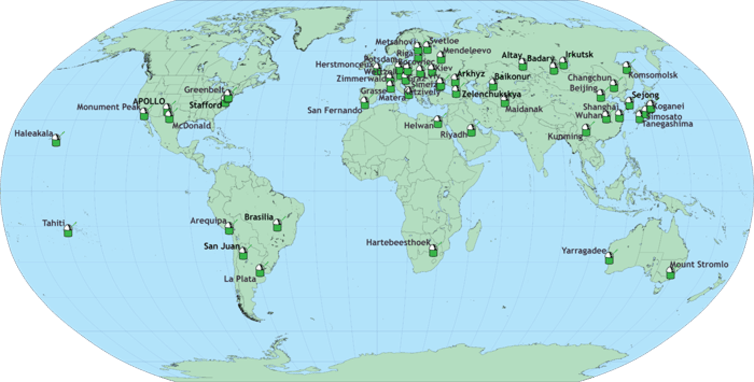

Every day, 35 satellite laser ranging stations across the world send laser pulses up to intercept the LAGEOS satellites. Two of these stations are located in Australia, at Mt Stromlo in the ACT and Yarragadee in WA. The Mt Stromlo facility is also used to track space junk.

The process works like this. A telescope emits a laser beam aimed at the satellite, which strikes the glass eyes and is deflected back towards the Earth, where the telescope receives it.

The length of time taken for the two-way roundtrip indicates how far away the satellite is. Once the time is recorded and corrected, we know the distance to the satellite at that moment to centimetre accuracy.

Laser ranging stations across the world. International Laser Ranging Service

The changes in this distance over time relate to variations in the Earth’s gravitational field and rotation, as well as environmental factors in orbital space.

The LAGEOS satellites (although the most beautiful) are not the only targets of the laser ranging network. Other satellites equipped with retroreflectors include the Russian BLITS (Ball Lens in Space) and ETALON 1 and 2, and the student-run Starshine satellites.

There are also retroreflectors on the Moon – at the Apollo 11, 14 and 15 landing sites, and on the Russian Lunokhod 1 and 2 rovers.

The measurements are coordinated and disseminated by the International Laser Ranging Service.

The information provided by LAGEOS 1 and 2 has contributed to new perspectives of the Earth, as former project scientist David E. Smith explains:

Today, we see Earth as one system, with the planet’s shape, rotation, atmosphere, gravitational field and the motions of the continents all connected. We take it for granted now, but LAGEOS helped us arrive at that view.

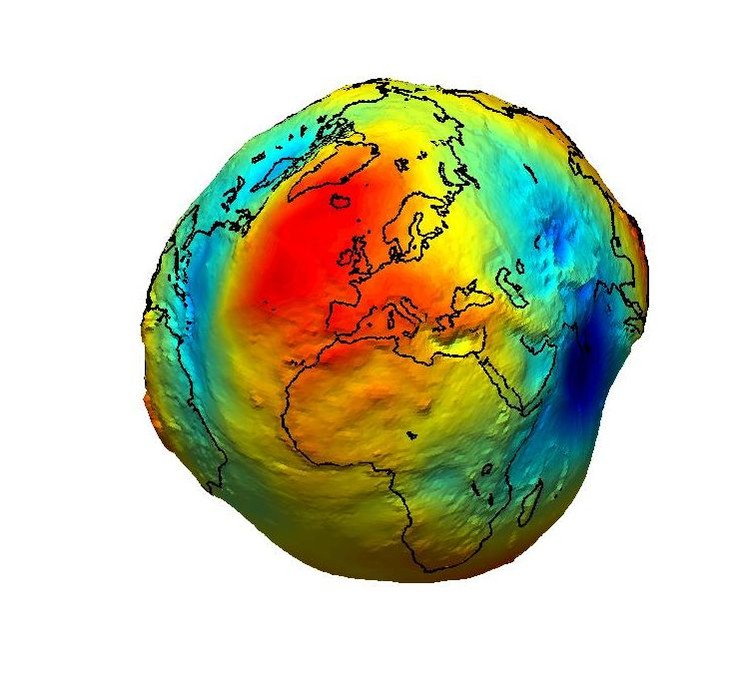

We tend to think of the Earth as a perfect sphere, but the distribution of mass within it is actually rather lumpy, which means gravitational force is not equally distributed.

Variations in the satellites’ positions have helped scientists to accurately map this distribution to increase our knowledge of the invisible geoid under the surface.

The geoid is the surface of equal gravitational potential of a hypothetical ocean at rest and serves as the classical reference for all topographical features. ESA

The geoid is a representation of the Earth if you remove the influence of tidal and atmospheric forces and imagine sea levels where they would lie according to gravity alone.

Even more importantly, the two LAGEOS satellites define the centre point, based on the Earth’s centre of mass, for the International Terrestrial Reference System used in navigation.

Another purpose is to measure the speed and direction of tectonic plate movement, which causes continental drift.

Both LAGEOS satellites are completely passive with no instruments, and no fuel and batteries to run out, which means they could outlast humanity. Their orbits may be stable for about 8.4 million years, according to the original prediction.

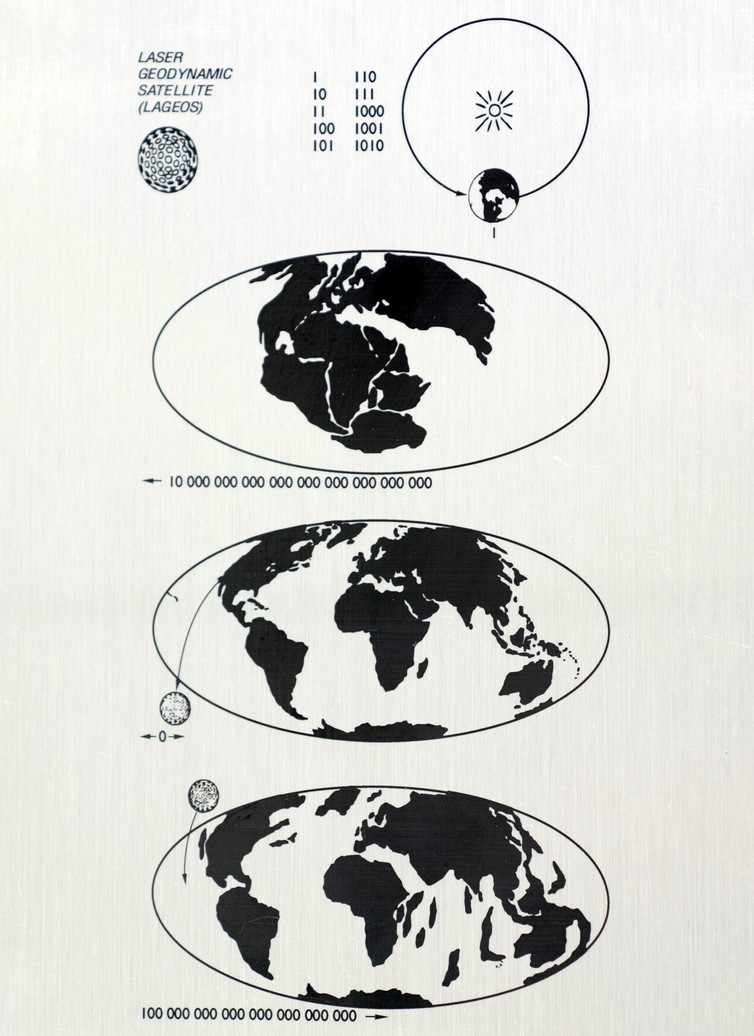

LAGEOS-1 is the bearer of one of Carl Sagan‘s time-travelling interspecies communications.

He conceived a design – drawn by Jon Lomberg who also worked with him on the Voyager Golden Records – depicting continental drift at three points in time: 268 million years ago when there was only the supercontinent Pangaea, 1976 when the satellite was launched, and a projection 8.4 million years into the future. The maps are engraved on a thin steel plate that was wrapped around the brass cylinder core.

You’d have to crack the satellite open like an egg, though, to get at the message.

It’s precisely the sort of alien mystery object that science fiction writers imagine falling to a planet and catalysing personal and social revelations, even when the object is impenetrable.

The LAGEOS-1 plaque. At the top, the numbers one through ten are written in binary notation, and Earth is shown orbiting the Sun. The three lower panels depict maps of Earth at different epochs. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Who knows who or what might find it in 8.4 million years, if it lasts that long. Will it melt in re-entry, fall into the ocean unnoticed and unmourned, or slam into what remains of Australia like Skylab, to lie under the stars for another few million years?

Dr Alice Gorman, who publishes the blog Space Age Archaeology, will present two papers, on space junk and also the archaeology of the International Space Station with US colleague Justin Walsh, at the International Aeronautical Conference in Adelaide in September. She is a Senior Lecturer in archaeology and space studies at Flinders University, and a member of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, the Space Industry Association of Australia, and the World Archaeological Congress Space Heritage Task Force.