Her Majesty and the horseman

The tale of Barossa horse educator Peter Jones’ connection with Elizabeth II is more than just another ‘day I met the Queen’ yarn. Simon Royal explains.

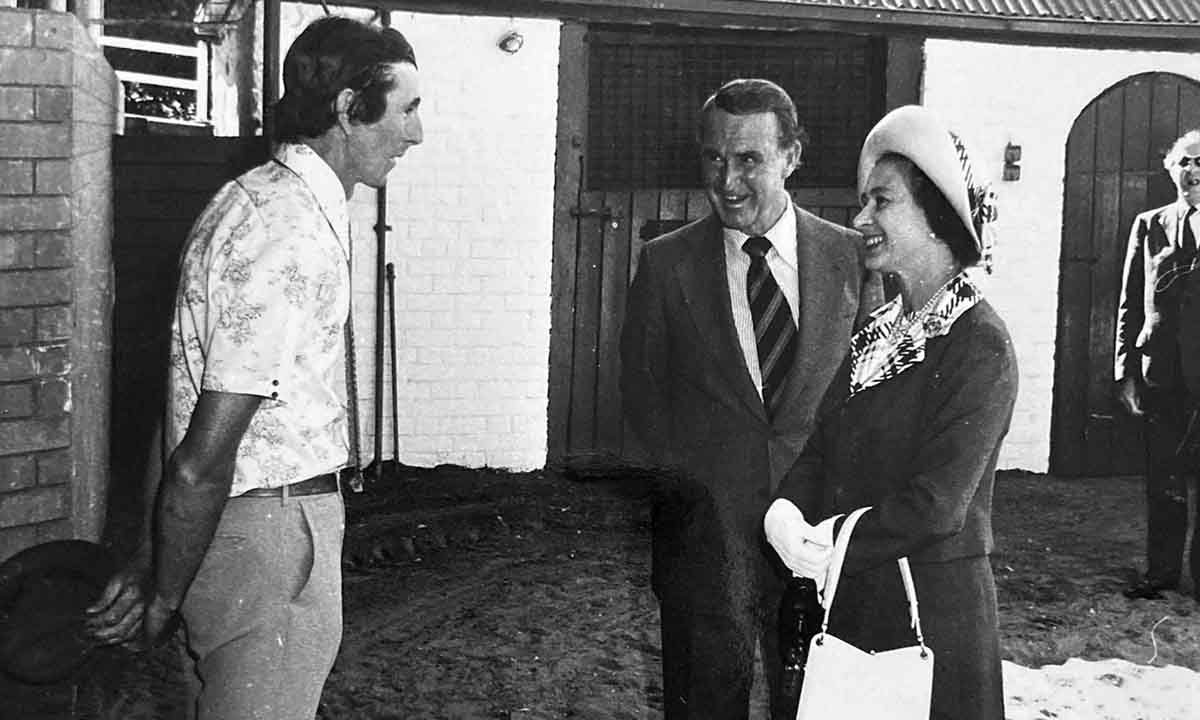

Peter Jones, Colin Hayes and Queen Elizabeth with 'Without Fear'.

With a quiet word and a gentle touch on the rein, one of the world’s most famous horses dipped his head to greet one of the world’s most famous women.

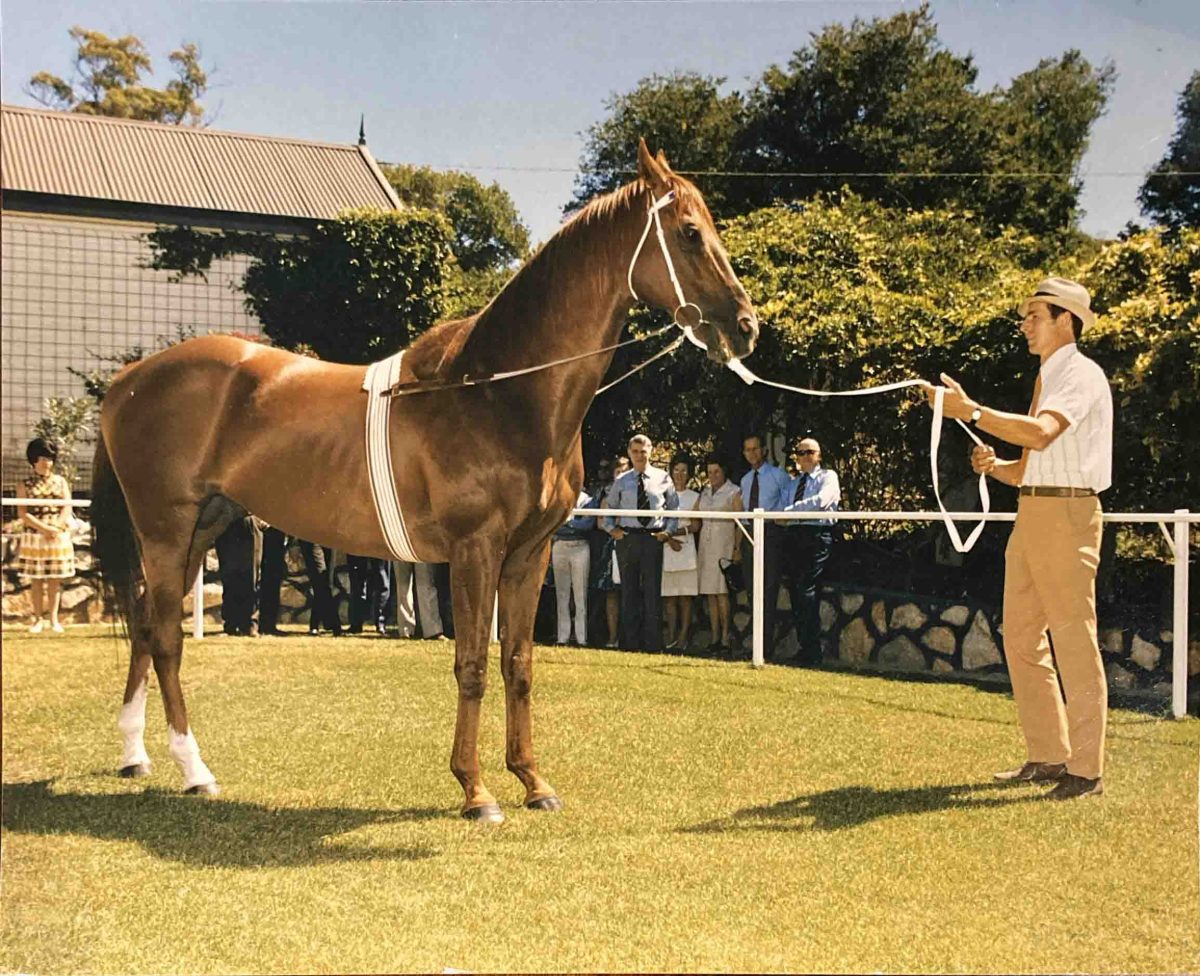

The horse – a stallion – was “Without Fear”. The woman was Queen Elizabeth II. The tall, softly spoken horseman who engineered the moment was Peter Jones.

“She [the Queen] had asked if she could come in the ring and hold Without Fear, give him a pat on the shoulder,” Jones recalls. “Of course we said yes. As she reached for the main rein, I gave the side rein a touch, and down went his head.”

The Queen, Mr Jones, and the horse, met on a sunny March day in 1977, at Lindsay Park stud in the Barossa Valley. The monarch was on her silver jubilee tour of Australia, taking in all of the states.

There are a couple of reasons why the Queen would want a visit to a horse stud on her South Australian schedule. Chief among them was the fact she really loved horses, and had her own highly successful racing stables. Lindsay Park and its owner, trainer Colin Hayes, were internationally recognised for their breeding of thoroughbreds. And “Without Fear” was equine aristocracy in his own right – all in all, fit company for a Queen.

“Without Fear was a champion”, Jones says. “He’d just created a worldwide record for the number of two-year-old winners he’d sired, and the fact that Colin Hayes had trained most of them, and I’d educated the majority of them… so the Queen was interested in our methods of educating two-year-olds.” The horseman was 41 at the time of the Royal visit, but already he’d made a lifelong quest of finding better ways to teach horses. Jones, and his methods, had gathered a reputation of their own which The Daily Mail, reporting back for its British audience, completely mangled the meaning of.

“He [Jones] is accorded much the same national esteem as we show to headmasters of Eton”, the Mail gushed.

Forty-five years later, that line still has the power to make the horseman blush.

“Bloody hell, who’d write this rubbish”, Jones says, half muttering, half chuckling as his face grows a little red.

In truth, Jones’s notions of how best to educate young creatures was the absolute antithesis of Etonian rigidity and stuffiness.

Peter Jones with Colin Hayes and Queen Elizabeth.

Peter Jones doesn’t actually remember learning how to ride, much the same as people generally don’t remember learning how to walk. Growing up in the UK after World War Two, his life was intertwined with the animals from the beginning.

“We had a pony, and I was on draught horses riding them out to the fields on the Isle of Wight when I was growing up”, Jones says. “I’ve always known horses. I was very fortunate to be around people, and taught by people, who relied on horses for their living, like my grandfather. When I came to Australia, [aged 14, in 1950] I worked for a bushman who in the same way relied on his horse teams. He’d be so far away from the lead horse, he couldn’t use the reins, so he’d use his voice to get them to turn left or turn right, or so on.”

Jones drew a couple of crucial lessons from those early experiences. The first is that reliance must breed respect.

“It’s the ability to create a rapport, no matter what the situation or circumstances or the age of the horse,” Jones says. “To respect the horse as a living being… A horse’s education has got to benefit it as well. An educated horse is much less likely to injure or hurt itself than one that’s uneducated.”

“I don’t think she really wanted to leave Lindsay Park that day.”

But it was the bushman’s voice that resonated just as much, if not more, with Peter Jones. He set about understanding how to communicate with a horse using the voice, rather than solely relying upon reins or stirrups.

“Personally, I believe you’ve got to project a suitable voice tone towards the horse to create a sense of reassurance and confidence in the horse’s mind,” he explains. “It’s not just a calm tone: that’s part of the usage of the voice, but not all of it. It’s the projection of the voice, with a certain tone. It’s no good carrying on with one tone all the time – ‘nah, nah, nah’. You might move faster in a sharper tone, and then a nice easy down tone to indicate a slower attitude to the animal, so that’s the basic idea. I think they are the fundamentals… irrespective of whether you want to horse for racing or riding for pleasure, or whatever.”

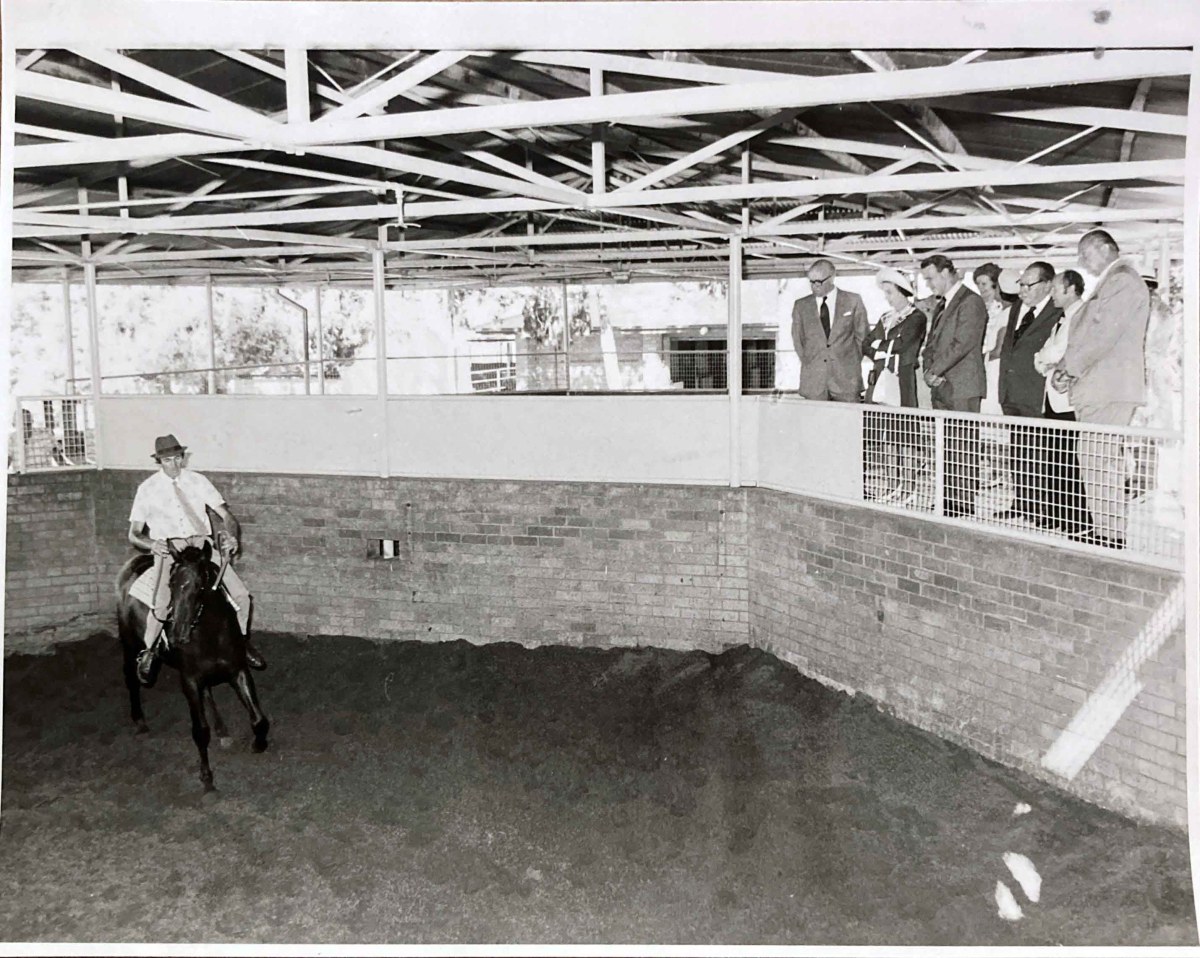

Peter Jones demonstrates voice control for the Queen.

Peter Jones continues his demonstration for the Queen.

Unsurprisingly, Jones has no time for the idea of ‘breaking a horse in’.

“I do not like it at all, “ he says. “It is an old-fashioned term… You are not breaking an animal … if that’s what you are doing then, well,” Jones finishes the thought with a disapproving shake of his head.

Despite popular beliefs, Peter Jones says he was given very little ‘education’ prior to the Queen’s visit. There was none of the usual stuff of films and dramas – ‘don’t turn your back on her’, ‘don’t speak unless you are spoken to’, or ‘ma’am rhymes with jam and ham, not farm and barn’. No one sought to train the trainer, though Colin Hayes had one piece of advice for his leading horseman.

“They didn’t say anything, just put a tie on, that’s all. CS [Hayes] told me to go out and buy a tie, so I did”, Jones says. He chose one in a spectacular shade of burnt orange, complete with a fringe – it was the ’70s, which explains everything.

As the Royal car drew up the long driveway at Lindsay Park, Jones wasn’t expecting to give the monarch a demonstration of how to use the voice alone to instruct and control a young horse. That wasn’t on the schedule – Without Fear, the aristocrat, was meant to be the star of the show. The Queen, though, had other ideas. Schedule be damned, she wanted to see and hear Jones’s methods for herself.

“It was just her and CS [Hayes] and I in the ring when we were showing her the training with the voice and the hands,” Jones recalls. “We added all of that on to what she was meant to see there. It went way over time, but no one interfered, so I don’t know if the officials were annoyed about that. No one hurried her. She was there with horses and that was it.

“She had a great knowledge of what goes on in a horse’s head. Not everybody has that in-depth understanding. Not everyone can respond to the fact that you can talk to a horse and, if you know what to do, that horse will reply in some form, but she knew. It was obvious.”

The horseman pauses, and then adds: “I don’t think she really wanted to leave Lindsay Park that day.”

Peter Jones in 1974 during a visit by the Duke of Edinburgh (in the background) to Lindsay Park.

In the week of wallpaper coverage following Queen Elizabeth’s death, there is a bit more to Peter Jones’s story than merely another man’s recollections of, ‘the day I met Her Majesty’.

In 1977, South Australia had a large and healthy thoroughbred industry – a network of studs dotted around the state, with Lindsay Park at the apex. The wider industry was touted as South Australia’s third largest employer. Today, it’s a frail shadow of when the Queen visited.

Colin Hayes is long dead. His son, David Hayes, shifted the training side of Lindsay Park to Victoria more than a decade ago, while other smaller studs have disappeared completely. Horse paddocks have become vineyards or housing estates. The look and feel of many country towns has changed. All the services that rode with the horse – the stock agents, fodder stores, specialist veterinary services, and so on – have dwindled, too. Peter Jones’s story is an insight into that – a perspective on us – with our shifting fortunes and tastes.

Despite its ‘gush’, The Daily Mail did have a moment of unintended prescience. After his time at Lindsay Park, Jones turned to teaching, spending a decade at Roseworthy Agricultural College.

When asked the usual question -‘ what did it mean to you, meeting the Queen?’ – Peter Jones doesn’t reach for the usual suspects like, ‘honoured’, ‘privileged’, and ‘proud’. No doubt he feels those things, it’s just that the horseman generally saves his words for something else.

“Well, it was the chance to communicate with another horse person, or a horsewoman, with a real horsewoman, that was something special”, Jones says. “After a few words, you forget you are talking to the Queen. You are just both talking about the horse and your life with them.”