The ‘King of Topham Mall’ and the kindness of strangers

All Gavin Friday ever wanted was to be in the news.

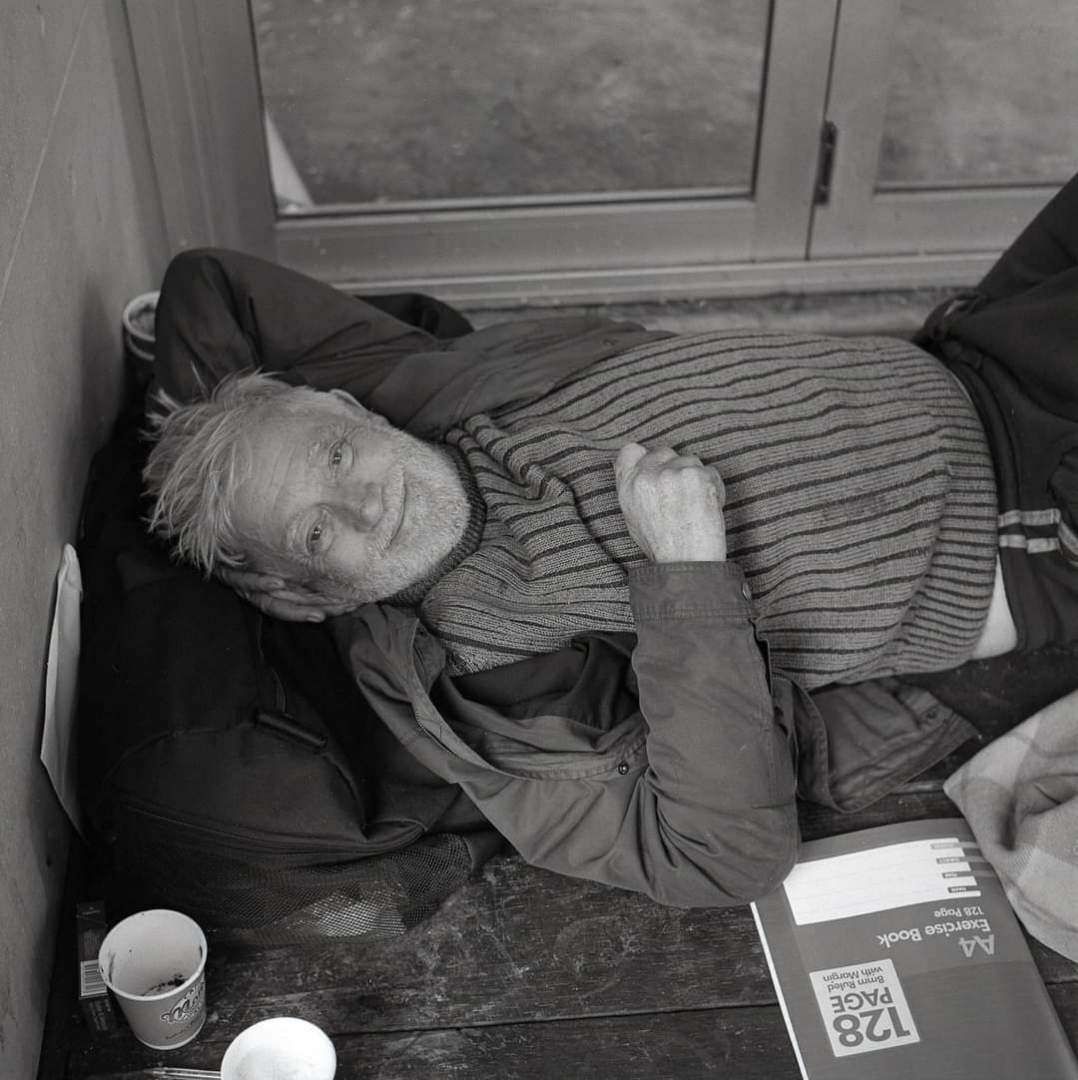

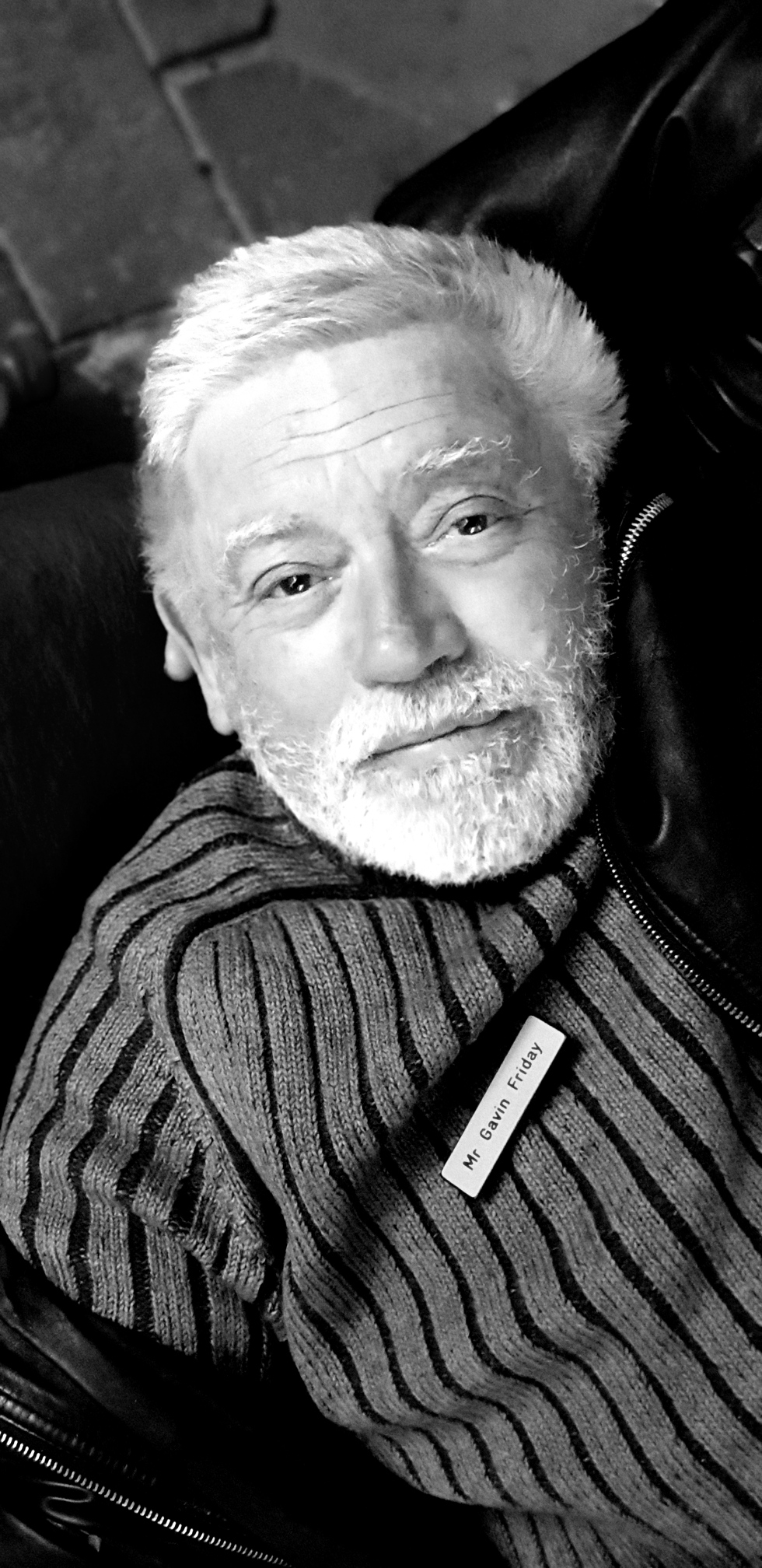

Gavin Friday. Photo: Chris Lambert. Image: Tom Aldahn/InDaily

From a coffee shop in Topham Mall, he’d sit at the same table each morning and sip a cappuccino, penning letters to Police Commissioner Grant Stevens – offering his thoughts on how to solve the latest crime, what could be done to reduce drug use in Adelaide or even where the missing Beaumont children might be.

Gavin was homeless and had schizophrenia.

His friends say he was also a gentleman and kind; larger than life – in character if not height.

The 67-year-old died in a nursing home in February after being taken off the streets two years earlier by authorities at the height of the pandemic.

In death he has been reunited with his estranged family, thanks to the kindness of strangers, who became his community.

Oliver Beres grins as he recalls the first time he met Gavin while making his way through Topham Mall in the morning peak hour rush on the way to work.

“He actually approached me,” Oliver says.

“I used to wear my suit with sneakers and he approached me saying, ‘You know it’s a bit odd’ – in a friendly way – ‘that you’ve got sneakers on with your suit?’

“And that’s how we formed a connection.”

From the park bench where he slept in Topham Mall between Currie and Waymouth streets in the heart of the business district, Gavin would regularly spot Oliver’s sneakers among the throng of business shoes and jump at the chance for a chat.

Oliver was happy to oblige. Mostly.

“If I was running late for a meeting, I’d say to myself, ‘Geez I hope Gavin doesn’t see me’ and I’d try to avoid him,” he laughs.

“He’d be lying down and he’d see my sneakers and he’d go, ‘Oliver, Oliver!’”

Oliver’s recollection is one familiar to Chris Lambert, another city worker who Gavin befriended.

“That’s exactly what he was like,” she chimes in. “Exactly like that!”

Chris and Oliver didn’t know each other before they met Gavin separately.

He had a way of bringing people together.

And he was persistent.

Oliver continues with his anecdote, explaining how their first meeting set the template for what became a regular fixture of his morning rush to work.

“He’d say ‘just a minute’. I’d say ‘Gavin, I’m running late.’ He’d say ‘But no, no, no, just a minute. Fifteen minutes later, I’d be late for my appointment.”

A situation Chris also got to know well.

“During peak hour, I’d catch the train and I’d have a meeting, I’d be, ‘Shit, where’s Gavin?’” she says.

“I’d try and tuck myself in with the crowd. Then: ‘Chris, Chris!’”

Gavin’s siblings roar with laughter hearing these stories – but it’s bittersweet, of course.

Living interstate, they hadn’t seen their brother for two decades. And now it’s too late.

With eyes red and wet, they sit on the park bench that was Gavin’s bed, soaking up every snippet of their brother’s life on the streets of Adelaide; wondering was he cold? Did he have enough to eat? Was he a nuisance and bad for businesses in the strip? Could they have done more to reconnect with him when he was alive?

Sister Glenys Chirgwin and brother Philip Tagg have come from Victoria to meet Chris and Oliver, to thank these two city workers for doing what most wouldn’t.

“I had to come to thank them,” says Glenys, dabbing her eyes with a café serviette.

“People went over and above to help him – these champion people here. I cannot thank you enough.”

“He was easy to love,” Chris tells her.

Emotional journey: Glenys Chirgwin and Philip Tagg sit on the park bench outside Topham Mall where their brother Gavin often slept. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Gavin’s siblings also want to see first-hand where Gavin was sleeping rough before he was scooped up by authorities two years ago and taken first to hospital under a mental health order and then to a nursing home, where he would live his final days – still occasionally writing to the Police Commissioner, when his ailing health would allow, and asking his friends if they would be so kind as to bring in a stamp on their regular visits.

It’s a week after Gavin’s funeral when Glenys and Philip make this emotional journey.

“As soon as I got the call from Chris to say he’d passed away, I said, ‘I have to go to Adelaide,’” Glenys says.

“As soon as I said it to Phil he said, ‘I’m coming with you.’”

Now, visiting their late brother’s long-time home – a thoroughfare for indifferent commuters – their inner turmoil is plain to see.

As is their gratitude to learn Gavin had some meaningful connections.

Chris and Oliver – Gavin’s “guardian angels” according to his siblings – not only befriended their delusional brother and looked out for him during his last years, they tracked down his family so they could lay him to rest in a grave next to their mum and dad.

“That’s why I had to come here,” says Glenys, through tears.

Chris Lambert, Philip Tagg, Glenys Chirgwin and Oliver Beres outside Topham Mall, reflecting on Gavin’s life. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Glenys says one of the last times she saw Gavin was at their mother’s funeral in Melbourne, 20 years ago.

“We only saw him for a day or two and then he was gone again,” she says.

“But Phil was in contact with him.”

Phil and Gavin used to go to the football together.

Gavin was a diehard Hawthorn supporter and Phil, more quietly spoken than his brother, was amazed at how easily he could talk his way into the clubrooms after a game, even during finals.

Phil says for quite a while Gavin held down a job and was living in an apartment in St Kilda.

“We’d take him home every Saturday,” he says.

“He’d go from work to the ground and I’d drive him home. He used to work in Spencer St in Melbourne and he’d get the tram to the ground. We’d meet him at the social club and we’d just drive him home.”

Phil’s wife Maree says it wasn’t just football that Gavin was fanatical about.

“His kitchen, there wasn’t a cup on the bench, so tidy,” she says.

“He was always on time. If Gavin said 11 o’clock, it was 11 o’clock.”

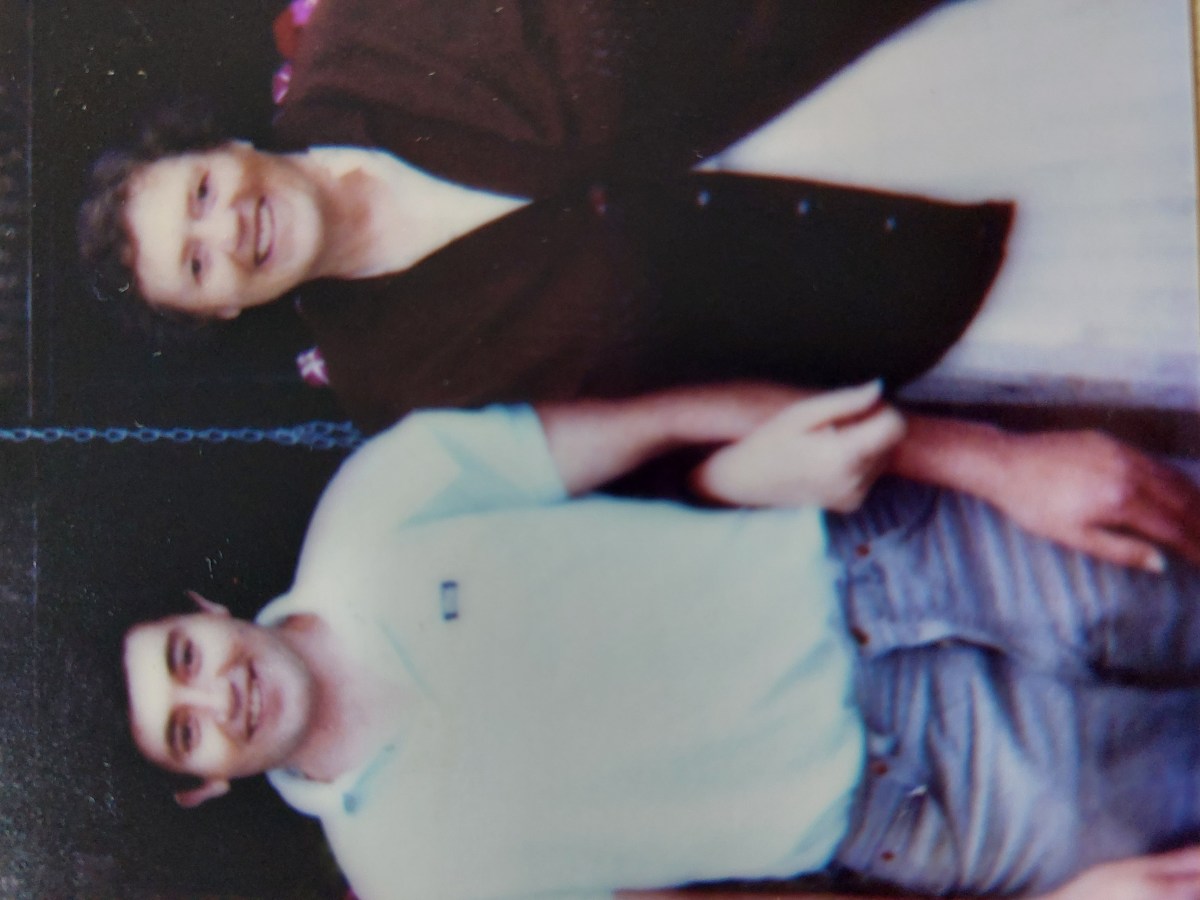

Gavin (front) with brother Philip and Philip’s wife Maree. Photo: supplied by family

But eventually it wasn’t easy for his family to maintain a long-term relationship with Gavin.

“He’d just disappear,” Phil says.

“No phone calls. Nothing.”

The King of Topham Mall

Chris and Oliver weren’t Gavin’s only friends.

He had a third “guardian angel”, although she would describe it as the other way around.

“I loved Gavin,” says Jo Parletta, who works at the coffee shop, Likuid Espresso, where Gavin would sit and write each day.

“He used to man the shop for us.”

“Did he?!” asks Glenys.

“He did – every night,” says Jo.

“He used to sleep in our front door and every night when I’d leave, even when I thought he was asleep, I’d walk past and he’d say, ‘Goodnight Jo. Don’t worry, I’ll watch the shop for you tonight, everything will be fine.’

“And every morning when I’d get to work about 4.30… I’d sneak past him really quietly and he’d just all of a sudden: ‘Good morning Jo!’

“And then every night, he’d say, ‘Have sweet dreams, don’t worry about anything tonight, I’m here.’ Every night, without fail. Everybody loved him. Everybody loved him. He was such a beautiful person.”

Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Jo says she would always ask Gavin if he needed anything, but he’d insist he didn’t.

“He never wanted anything from anybody,” she says.

“He came to me one day and he said, ‘It’s so lovely Jo, these people, they brought me these blankets and these clothes and I really appreciate it but I don’t need anything. And they just left it by me while I was sleeping.’ And he said, “I don’t want anyone to bring anything for me. I’m fine. I’m happy.’”

Coffee shop regulars would sometimes set up accounts for Gavin to ensure he didn’t go without.

“We’d give him a coffee first thing in the morning and then some mornings you would have four or five customers order him a coffee,” Jo says.

“And I would say, ‘Oh, he’s got one on the go at the moment’. Because sometimes he’d have like four coffees sitting around him and he’d say, ‘Jo, everyone keeps giving me coffee but I’ve got coffee’.

“And so then we would just put it on a tab for him so when he wanted it he could come and ask for it. People would order him lunch for the day ahead, they’d order him lunch for the week ahead. It was lovely.”

It’s been two years since Gavin was taken off the streets, before his recent death.

“People still ask me if I’ve heard anything, if I know anything about Gavin,” Jo says.

“People still ask all the time.”

This prompts his brother to ask a question he’s been pondering.

“So he was no trouble?” Phil wonders.

“Oh my God, no,” says Jo.

“He used to get rid of all the trouble that was around here.

“Sometimes there would be some trouble-makers around and he would say, ‘They’re not my friends Jo, you make sure you know I don’t know them, I don’t like them in our world and I’ve told them they can’t stay, they have to leave’.

“He would look after the whole mall.”

Oliver says he was “the King of Topham Mall”.

A portrait of Gavin Friday by photographic artist Alex Frayne, used with permission.

“That’s what we called him – the King of Topham Mall. He really was. For such a small fellow, in his 60s, he commanded such control and respect.”

Chris clarifies: “He was a gentleman though.”

Jo agrees: “Yeah, he was. He was lovely.”

Thinking of scenes involving others that he has witnessed on the streets, Phil probes further, asking Jo: “Your boss, he’s not worried about his business and making a living? Gavin could have been…”

Before the question is even finished Jo says firmly: “Gavin was absolutely no trouble. At all. Ever ever. Not ever.”

How long Gavin lived in Topham Mall is not clear.

The coffee shop in the mall where Jo works has been there five years. Gavin was a staple from the beginning; his daily order – medium cappuccino, no sugar.

“And he used to just write,” says Jo.

“He used to have his coffee and he’d have a little allocated table inside and he’d come in with his little notebook and he’d just write stories and drink his coffee in the morning.”

What did he write?

“All sorts – he used to write stories… most of them you couldn’t make a lot of sense of when you were reading them, but he brought me in a book once,” says Jo.

“It was all sorts of hilarious.”

It’s also not clear when Gavin’s mental illness began to take over his life.

Phil and Glenys say that when he was in his 20s and 30s and working at a camping shop, he seemed “fine”.

“I would have picked nothing wrong with him,” Phil says, “except he had a little bit of a stutter”.

“You weren’t aware he’d been diagnosed?” Chris asks.

Phil says he had “no idea.”

Glenys, however, recalls her brother once giving her a book he’d made, when she was in her mid-to-late 20s.

“[It was] about five or six pages long… when I started reading it I realised there wasn’t something quite right,” she says.

“He had really nice drawings. He had flowers all around the walls and these flowers were talking to each other, in the story.”

It was an inkling, she now says, into Gavin’s emerging mental health struggles.

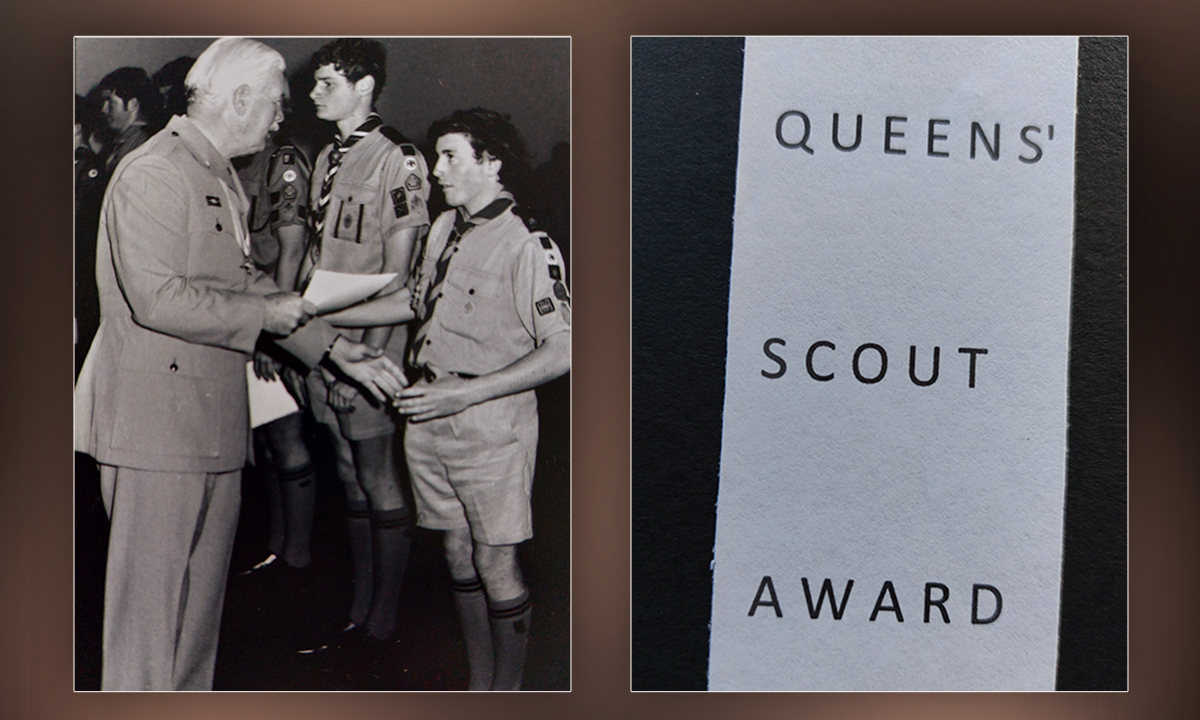

Gavin as a teenager receiving a Queens’ Scout Award. Photo: supplied by family

Oliver says there were “some days he’d be sitting at the table in the coffee shop and I’d say to myself, ‘Oh, I wonder what the coffee shop owners would think of that’, and he’d be writing away and he’d get in the zone – so I’d go to see how he was [and] he was like ‘piss off, cos I’m busy writing’”.

“When he was in that zone he was a prolific writer,” he adds.

Oliver says Gavin would regularly write to the Police Commissioner.

“He’d say to me, ‘I wonder if they got it?’” Oliver says.

“I said, ‘They got the letters’.

“Because he had three officers one day, the Commissioner sent three officers around to have a chat to him about all this writing. Through these three officers the Police Commissioner wanted to let Gavin know he’s got a cupboard full of his letters. And would he stop.”

A portrait of Gavin Friday by photographic artist Alex Frayne, used with permission.

The world’s greatest problem solver

Oliver called Gavin “the world’s greatest problem solver”.

“All his ramblings through his writings were essentially trying to solve problems,” he says.

“It could have been the Beaumont children, car accidents, drug use. A lot of the social issues. He was trying to come up with a solution.”

“Even when he was in the nursing home and I used to go and visit him he’d have letters for me to post to the Police Commissioner.”

Stevens himself declined to address his regular correspondent, a spokesman saying: “We are unable to make comment on the details relating to letters written to the Commissioner.”

Chris recounts phone calls from Gavin while he was in the nursing home, asking for stationery.

“He’d say, ‘Chris, can you send me some writing paper, I’ve run out?’” she says.

“I’d say, ‘Ask someone at the desk. And he’d go, ‘No they won’t. And I need a pen and I need some more envelopes, and you don’t need to send stamps because Oliver is coming on Saturday.”

Oliver says “he’d ring me up sometimes and say, ‘Don’t worry about coming in this week. I don’t have a letter to post’”.

“He’d think I’m coming in to just pick up his letters,” Oliver smiles – drawing a laugh from Gavin’s family.

Then Oliver turns quiet.

“The last six or seven months he sort of gave up and I think he knew his body was deteriorating and he gave up hope and he stopped writing. I used to try to encourage him: ‘Have you got anything? What are your thoughts today?’”

Chris wonders if medication was affecting him.

Oliver agrees he appeared “heavily medicated” in hospital.

“They were trying to find a way for him to realise that a lot of his thoughts weren’t real,” he says.

“But he wouldn’t accept it. They only gave him that heavy medication perhaps for a month. He was still writing, having the same thoughts, the same levels of energy and enthusiasm and delusion.

“There was no way that any medication was going to change him. That was evident to me very early on in the piece, when they took him off the street due to COVID and put him in the mental health ward to do an assessment.”

Chris wonders if moving Gavin out of Topham Mall, where he had a community, accelerated his decline.

Oliver says he, Chris and Jo weren’t the only ones looking out for Gavin, and others.

“There were people that would order food and send Uber Eats to deliver food to him,” he says.

“Not just to him but to a couple of others. I was here one Sunday for Easter just as COVID broke out, dropping off an Easter egg, and I experienced this Uber driver turning up with a couple of meals and another homeless person saying ‘Gavin, which meal do you want?’ Gavin was trying to tell him to go away. He was very territorial. He felt like this was his patch and he didn’t want other people to interfere with his relationships with people.”

Chris reckons Gavin believed he was “on a very good wicket”.

“And that’s why I think when they would have come in and said we’re offering you a hotel, he would have gone ‘I’m not going to a bloody hotel’. It was his community here,” she says.

The beginning of COVID

Jo was there the day authorities picked him up and she wanted to make sure he was being treated well.

“The officers came and I was watching and then they started going through all his stuff and I said to my boss, ‘What are they doing to Gavin? Leave him alone,’” she says.

“Gavin was just chatting to them and then about 10 minutes later, the ambulance came and then we went out and they came over to us and told us they were taking him. That was the beginning of COVID.

The bench next to Topham Mall where Gavin often slept. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

“We had heard that they were trying to get the homeless off the streets, just to give them checks and stuff, make sure they were ok. They said to us, ‘Don’t worry, he’s not in any trouble, we just want to make sure he’s ok, we’re taking him to the hospital just to give him a check’.

“So that night I rang the hospital and he was in emergency still. I talked to him. He was hilarious. He said, ‘Jo, these people are all crazy. And I don’t know why they won’t let me leave.’ I said, ‘Gavin, make sure you be nice to them’. He said, ‘Jo I’m always nice to everybody.’”

That’s the last time Jo spoke to Gavin.

“I thought maybe they were going to hold him for two weeks, so every day I would come in hoping he would be out the front and he wasn’t,” Jo says.

“It was finally Oliver who came in and said he knew where he was.”

By that point the King of Topham Mall was in a nursing home.

Oliver says the only time Gavin ever asked him for anything other than stamps or stationery for letters, was when he was in that nursing home, when he requested $20.

“I thought he’s going to get a taxi and take off so I was hesitant,” he says.

“Eventually, for his birthday, I gave him this $20. He was really happy. It’s the only time he ever asked me for anything.

“He had a pair of runners at the end of his bed. And his clothes would never be in the wardrobe. He was ready to take off. He used to say to me, ‘Oh the security here, I don’t know how I’m going to get through that front door.’”

Oliver says Gavin put the $20 note in a drawer.

“He said he wanted the money to buy stamps but he had money [through the nursing home]… I knew that he didn’t want to deal with them. He wanted this $20. First opportunity he could get out of there, he’d have money to catch a taxi.

“He didn’t say this. I was surmising.”

Oliver says he found out via another homeless person that Gavin had been taken off the streets.

“Through phone calls, I found him and went to visit him,” he says.

It was through his conversations with Gavin that Oliver initially connected with Chris.

He had tracked Gavin through the hospitals and would visit him weekly in the mental health ward.

“They would never tell me when they moved him but I tracked him down to the nursing home and I’d go and see him every two weeks,” he says.

“And through those visits, I’d just gain a bit more information out of him without being too intrusive or threatening.

“I used to sit there wondering, his family must surely want to know what the hell’s happened to this guy…

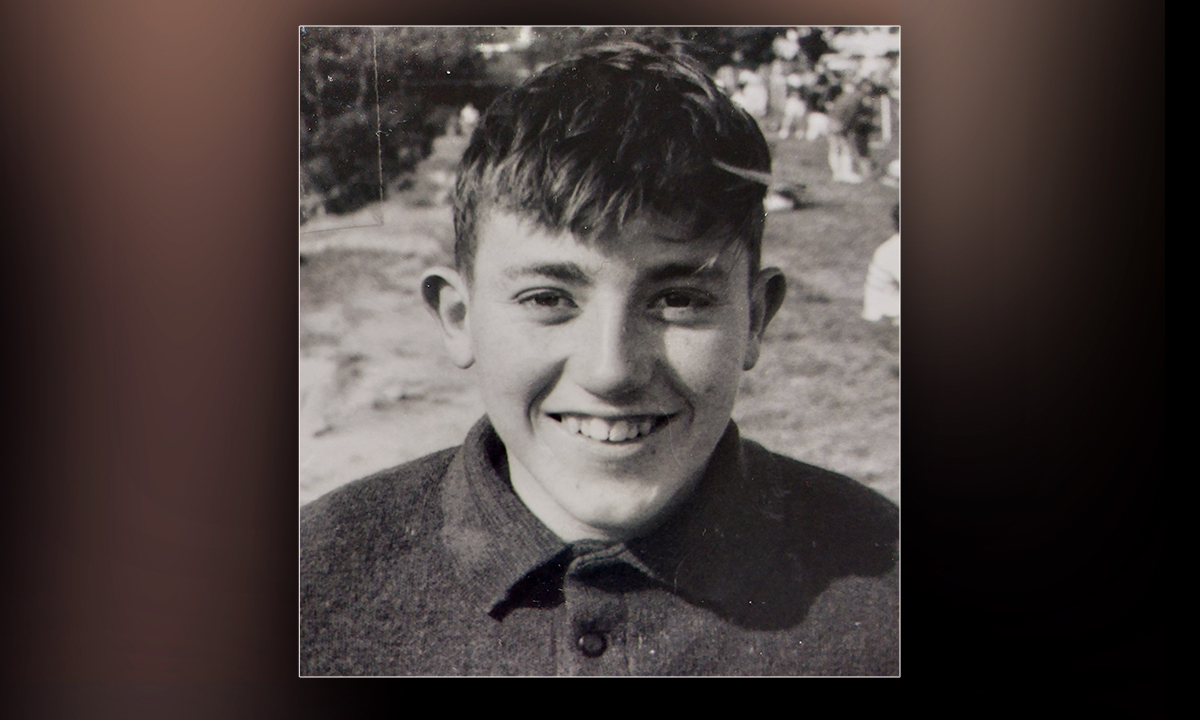

Gavin as a child. Photo: supplied by family

“Through different discussions on each visit I’d get a bit more. Then I found out this woman Chris had contacted his sister through Facebook. And then after another couple of visits I said ‘who’s this woman?’”

Gavin, it turned out, had Chris’s number – “one of the few possessions that he had… and that’s when I contacted Chris to let her know that Gavin was (now) in the nursing home”.

“Through Chris we found out his real name and that’s how in the end we connected with his family,” he says.

Gavin died before the family made it over, with Chris and Oliver bounced between bureaucracies to allow his body to be released for his funeral and burial beside his late parents in Melbourne.

Chris explains: “I spoke to the [Office of the Public Advocate]… I was saying ‘Gavin’s still at the nursing home the next day’ [after he died] and they said ‘well, we’re no longer responsible for Gavin because we were responsible for his healthcare but now he’s passed away’.

“I said, ‘well who’s his guardian?’ And she said, ‘he doesn’t have a guardian… he’s passed away.’ I said, ‘but he’s still got a body, who’s responsible for that?’ And she said, ‘that’s about financial decisions, you need to talk to the public trustee’… It was like ‘are you kidding me?!’”

“Without the advocacy of you and I,” she says to Oliver, “I don’t know what would have happened if we weren’t knocking on doors.”

Family reunion

Finally in Adelaide for the sombre reflection – a wake with old friends they had never before met – Gavin’s relatives have questions, but also, finally, answers.

Gavin as a young man with his mother. Photo: supplied by family

“In hindsight, why didn’t we chase him down?” Phil wonders aloud at one point, through tears.

“Really, he came here on a mission. He’s found friends.”

And it’s that friendship that best sums up his brother’s legacy in his Topham Mall kingdom.

“For me, it’s the love – of these two great people,” Phil says.

“To get him home.”

Glenys says she thought of Gavin often over the last 20 years: “I’ve been worried that he would be found dead somewhere. Buried somewhere and we’d never find him.”

“I just find the whole thing just so amazing… [these] amazing people – who does that for someone who is homeless?” she says.

“It just stopped all those questions about him. To bury him, to put him with Mum and Dad, that just meant everything to me.”

Gavin was laid to rest next to his mum and dad. Photo: supplied by family

Gavin’s relatives ask if there was any shouting and screaming when he was taken by ambulance.

“Not at all,” Jo says.

“He went happily – he just made sure he had his writing stuff in his backpack.”

Chris and Oliver say Gavin had delusions of grandeur classic in schizophrenia.

“He’d go ‘I’m the world’s smartest man, they’re all dumb’,” Oliver says.

Chris says he thought, ‘Well, they’re mad if they think I’ve got schizophrenia.”

“He didn’t see himself as the homeless guy that everyone helped,” she says.

“He saw himself probably as the one that looked after the café at night, wrote what was going on, wrote to the police. He saw himself as really important.”

For Chris, this story is about more than Gavin.

She recognises her friend was a sympathetic character “as a marginalised man” – he was easy to love, “a beautiful man”, she says – “but everybody deserves to have an opportunity to reconnect – everybody”.

“If anything, if there’s a wish from me beyond Gavin, it’s that there’s some effort put into reconnecting [other] families,” she adds.

“For me at the end of the day, it’s a good news story. I know that there’s sorrow. But if you think about all that he lived with, and all that we all live with, to think that someone like Gavin can come and be here and be so embraced and then reconnect… with his family. It’s actually a beautiful story.”

For her, it tells of “what can happen when you start to be more approaching to people who are marginalised, rather than keeping them at bay”.

But then, she concedes, “Gavin was very approachable in that sense.”

“He was really kind… just really sweet,” she says.

He would ask her how she was, how was her day, how her boys were going.

“He had empathy for the other. It was a two-way relationship,” she says.

“Always happy, never aggressive, never angry about anything.”

Oliver adds: “I’m so happy that we’ve got his body repatriated with his parents and he’s embraced by his family – that is like winning the lottery.”

“I describe him as a character,” he says.

Photo: Chris Lambert

“A true character. He had such a unique personality. He’d touch so many people. I suspect more people approached him than he approached them. He was never asking for anything.”

Glenys’s husband Bryan muses that despite his poverty, “it sounded like he wanted for not much”.

“Except to be on the news,” agrees Oliver.

Oliver explains why it wasn’t easy initially to keep in touch with Gavin after he’d been taken off the streets – partly because ‘Gavin Friday’ wasn’t his real name (despite the badge pinned to his shirt).

“The amazing thing for me with this story was the fact that he operated under an alias – Gavin Friday,” Oliver says.

“It was only through Chris that we realised his real name but he never shared that with me.”

When Glenys showed Phil one of Gavin’s medical certificates after his death, Phil was shocked to see the name ‘Gavin Friday’.

“I said what the hell’s he doing that for? It just threw us,” Phil says.

Why Gavin Friday?

“We don’t know,” say Phil and Glenys in unison.

Oliver ponders if he might have wanted to “get rid of any history” from his real name – Gavin Tagg – in terms of any prior diagnoses.

“I think that’s exactly right,” Chris says.

“And he liked Fridays would be my guess,” Phil’s wife Maree says.

Gavin’s friends explain too how he always believed fame would find him on a Friday.

“The irony in all of this is that part of why Gavin didn’t want to leave Topham Mall is because he thought any day now, he was going to be on the news,” Chris says.

“He was, ‘Any day now, it’s going to be this Friday’,” says Oliver.

“He’d try to find reasons why this particular Friday the news team was going to turn up.”

“It was always going to be on a Friday,” agrees Chris.

“All he wanted was to be on the news”.

Now he is.

Photo: Chris Lambert