Why Australia’s saint still shows the way for Catholics – and secularists

With a new museum celebrating Mary MacKillop set to open in Adelaide, Samela Harris recounts the feisty saint’s brave battles against disgraceful conduct – a campaign which resonates today.

A woman prays at the tomb of Mary MacKillop. Photo: AAP/Sergio Dionisio

From behind the shadow of scandals in the priesthood, a bright light has continued to shine for Roman Catholics.

It is Mary MacKillop, Australia’s first saint in whose honour a new high-tech museum is opening in Adelaide in December. She lived from 1842 to 1909.

In keeping with the generally unconventional character of Australia, our first saint was no namby-pamby. She was a feisty and fearless – a clever pioneer feminist who stood up for the dispossessed and confronted the disgraceful.

Little known by the world at large is the fact that it was the movement created by this groundbreaking nun which started the ball rolling for the outing of pedophile priests. It happened a century ago in Kadina, South Australia.

It was an important and very brave stance for nuns to take and, indeed, it has been more whispered than bragged about by subsequent generations of nuns. The implications for the church and for the faithful are many-layered. Even now, as court reports continue to hit international headlines, it is a subject that Mary MacKillop’s Sisters of St Joseph broach with reluctance and deepest sorrow – the almost incomprehensible betrayal of the sacred vocation of the priesthood.

Secular feminists, however, can’t help but brandish this historic flag. We see Mary MacKillop not so much as a religious figure, but as one of the greatest and most courageous feminists ever to stride this land.

She and her band of nuns, the Sisters of St Joseph, found themselves most affectionately known as Australia’s “Joeys”, and were the foundation of equality in education in this country. They insisted on teaching girls in an era when girls were not considered suitable for emancipated learning. They taught the poorest and most disadvantaged of children and accepted children of privilege equally, if required. They, themselves, chose to live in poverty and simplicity. In fact, the nuns were often seen begging in the streets.

… she was a woman stirring the pot in a male business.

When the Josephites spoke up, reporting through Julian Tenison Woods to the Vicar General that a priest called Father Keating in Kapunda had been molesting children at the little country school, the powerful patriarchy of the church turned against Mary and her Order. While Keating was humiliated and quietly sent back to Ireland with mutterings about alcohol abuse, his Adelaide defender, Father Horan, a close friend of then South Australian Bishop Sheil, was hellbent on finding ways to bring down Order of those whistleblower nuns. With cunning ecumenical politic, he engineered an attack not on Mary but on the constitution of the Order of St Joseph with a challenge which would have left the nuns homeless. Needless to say, Mary was having none of it and so came the justification to have her excommunicated for “insubordination”.

She had to go into hiding, forbidden from having contact with her Sisters. Lay friends, a Jewish family and the Jesuits helped to protect her as she moved from safe house to safe house.

It was a saga of priestly power and cover-ups from which Mary’s MacKillop was to eventually reemerge, reinstated in the church by a sick and dying Bishop Sheil to continue her work. A century later, she was to receive a formal apology from the Adelaide Archbishop of the day, Philip Wilson.

Mary MacKillop: a feisty, pioneering feminist. Supplied image

Mother Mary of the Cross, as she was known, was a fierce feminist long before the feminist movement took shape. She was a country girl of Scots parentage, raised in south-western Victoria before moving into South Australia as a governess and then creating a religious sisterhood and the first of what were to be many hundreds of schools. There was a man in her life, an intellectual pin-up called Julian Tenison Woods, a priest, a scientist, and a teacher. He saw the fire in the young Mary’s spirit, her hunger to learn and to give. He artfully pushed her forwards. Hence, the world has much for which to thank him.

Both Mary MacKillop and Julian Tenison Woods are celebrated in this new Adelaide museum which sits next to the Josephite Convent and beside MacKiIlop Park and the Mary MacKillop College in Kensington SA, an area which now is branded the Mary MacKillop Precinct.

Indeed, while the museum is a state-of-the-art attraction, the area around it is quietly drenched in the history of Saint Mary of the Cross MacKillop.

It was here in Kensington, Adelaide, where she set up her Mother House and rallied young women to join her order, the first Catholic order to be founded by an Australian. It was from here that she sent out teachers to find and help needy children and set up shelters for struggling mothers and those suffering. She created aged care for the sick and old. If she learned of outback children with no teacher or school, she would dispatch one of her fearless Brown Joeys in their rough and heavy chocolate-coloured robes. Little schools popped up everywhere and the outreach kept growing until it was national and there was a new and bigger Mother House set up in Sydney, which is where Mary finally died and is buried.

But it was from South Australia that the mighty movement spread its beautiful wings, firstly from the wee, humble school in Penola in the state’s volcanic southeast and then from the base in Adelaide’s Kensington, just a 40-minute walk from Adelaide’s city centre.

Inside the new Mary MacKillop Museum in Kensington.

Here remains the very beautiful little chapel where Mary and her Sisters of St Joseph worshipped. Next door to it is the modern girls’ school, Mary MacKillop College, wherein the students are multi-national and of diverse religious backgrounds, very much in the all-inclusive character of Saint Mary. Science and maths, like music and literature, reign high in the curriculum and the school quietly boasts streams of high achievers.

The emphasis on science in the MacKillop educational ethos was inspired by Mary’s friend and mentor, Julian Tenison Woods. He played a pivotal role in encouraging the young Mary, who began as a country governess, to brave her way to creating a school and an order. Tenison Woods was something of an inspirational character, a handsome and erudite young Catholic priest who explored the landscape on horseback. He was a geologist and also a journalist who founded a Catholic periodical and wrote for countless publications, often on scientific subjects. He was an award-winning expert on molluscs, for example. He believed in evolution and wished to see modern science find unequivocal proof for it.

He was educated in England and France and began as a parish priest in Penola, where he was the one to recognise the potential of young Mary. He went on to be the director of Catholic education in SA. Not only his role in the career of Mary MacKillop but generally, his emancipated spirit and his unusual relationship with his church as well as his scientific findings leave him as one of the most fascinating unsung heroes of Australian history.

He is, of course, remembered and celebrated in the new Mary MacKillop Precinct Museum.

Other benefactors played important roles in the success of Mary MacKillop. The Anglican family of the Barr-Smiths, Adelaide gentry of the day, appreciated and supported her work with generosity. And she had the support of the Adelaide Jewry in the form of the Solomon family.

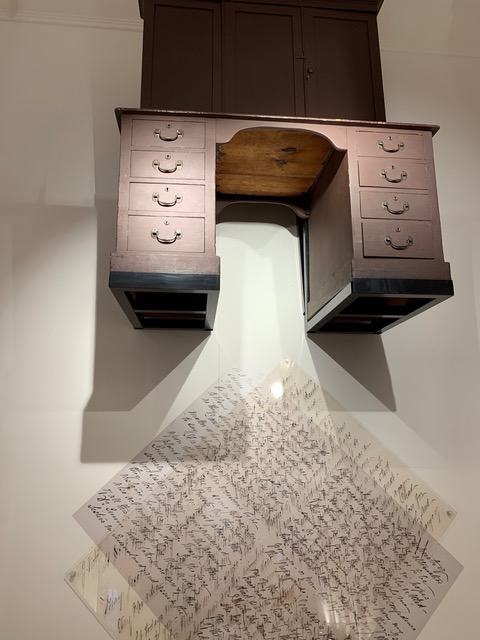

Of all things to be deemed a religious treasure…..for Australia’s pioneer teacher saint, it’s a desk – of course – featured at the new museum.

If anyone was to try to undermine this progressive humanist it was her own people, the men of the church, the establishment, the bishops. For many reasons, they wanted her off the landscape. They found her too demanding and too smart, too independent, too outspoken and, as things turned out, too dangerous. And she was a woman stirring the pot in a male business.

Oh yes, history has a way of eking out the truth.

There has been talk in Australia of making Saint Mary MacKillop of the Cross the Patron Saint of Victims of Abuse.

History finds that Australia’s first saint was a trail-blazing fighter for the rights of others, for fairness for all, and for a good education for everyone. She was a devout and respectful nun and yet an intellectually emancipated and progressive woman.

She stands now as a figure of pride for this country and, as Max Harris once said, “a saint for all Australians”.