Planners warn of climate change risks for Adelaide

SPECIAL REPORT | The way South Australians design their communities and their homes must change, planners warn, with the impacts of climate change a present reality. Stephanie Richards reports on how the state has been preparing its built form – and what needs to happen next.

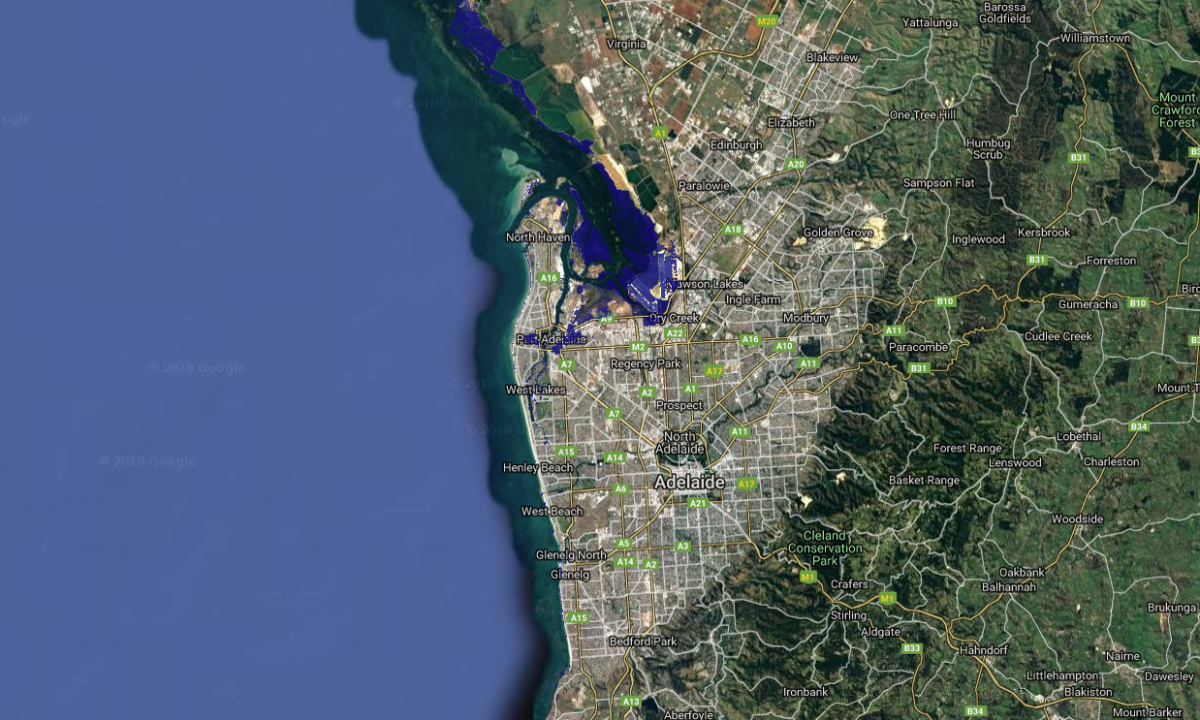

Adelaide's suburban coastline is vulnerable to sea-level rises. Photo: AAP/Kelly Barnes

As Adelaide swelters through an uncomfortable spate of record-breaking heat and dryness, the need for cooler, better-insulated buildings and shadier streets is more pressing than ever before.

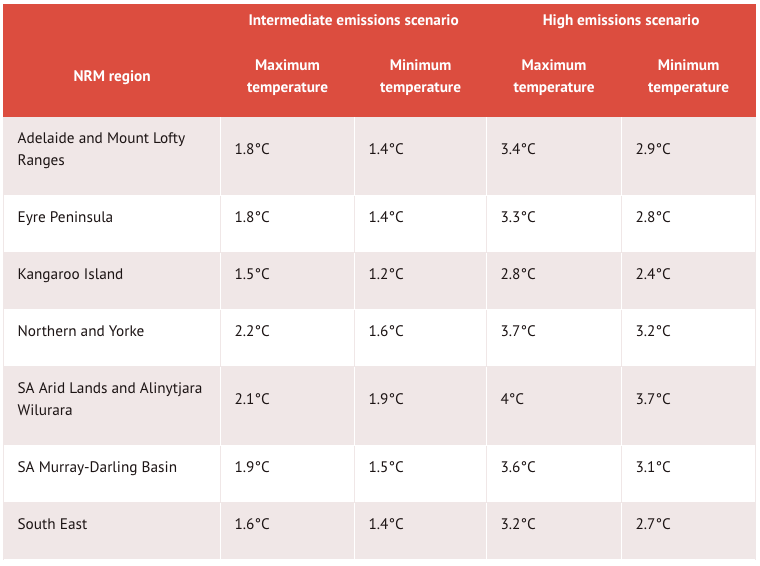

The number of days reaching over 40 degrees in Adelaide has more than doubled in the past 10 years, with the Bureau of Meteorology forecasting maximum daily temperatures for South Australia will rise by between 1 and 2.1 degrees by 2050.

But a temperature rise is just one part of South Australia’s climate outlook. According to the Environment Protection Authority, South Australian coasts have seen a sea level rise of 1.5-4mm each year since 1965. The EPA projects those levels to rise by about one metre by 2100.

Sea level rise is particularly concerning given the majority of South Australian towns are located within 50km of the coast. According to the EPA, more than 80 per cent of South Australians live within Greater Adelaide – much of which is a low-lying coastal area which the EPA says is vulnerable to sea-level rise and storm surge.

“Climate change is definitely something that people need to consider when thinking about planning decisions or building houses,” Adelaide Sustainable Building Network chair Ken Long said.

“We can’t just keep on designing as we’ve done before, because that’s just either going to get more expensive or it’s just simply not going to work.

“We need to work with nature’s forces a little bit more because we can’t always keep thinking that the climate is going to be nice.”

Long, a sustainability consultant who has advised on major building projects including Adelaide Airport and Lot 14 at the old Royal Adelaide Hospital site, said the SA planning industry has evolved to a point where it now considers climate projections in most building decisions.

His warning on climate change adaptation foreshadows a costly reality projected for South Australia’s coastline.

In 2011, a Federal Government report estimated that between 31,000 and 48,000 residential buildings in South Australia might be at risk of flooding from a sea level rise of 1.1 metres.

The study, which did not take into consideration existing coastal protection such as seawalls, also estimated that a sea level rise of 1.1 metres would put about 6700 km of roads, 200 km of railways, 1100 light industrial buildings and 1500 commercial buildings at risk in South Australia.

The replacement value, according to the report, was estimated at about $5-8 billion for at-risk homes, $22-27 billion for commercial buildings, $7 billion for roads and $0.6-1.3 billion for railways.

Adelaide’s current-day highest tide levels. Map: NGIS / Coastal Risk Australia

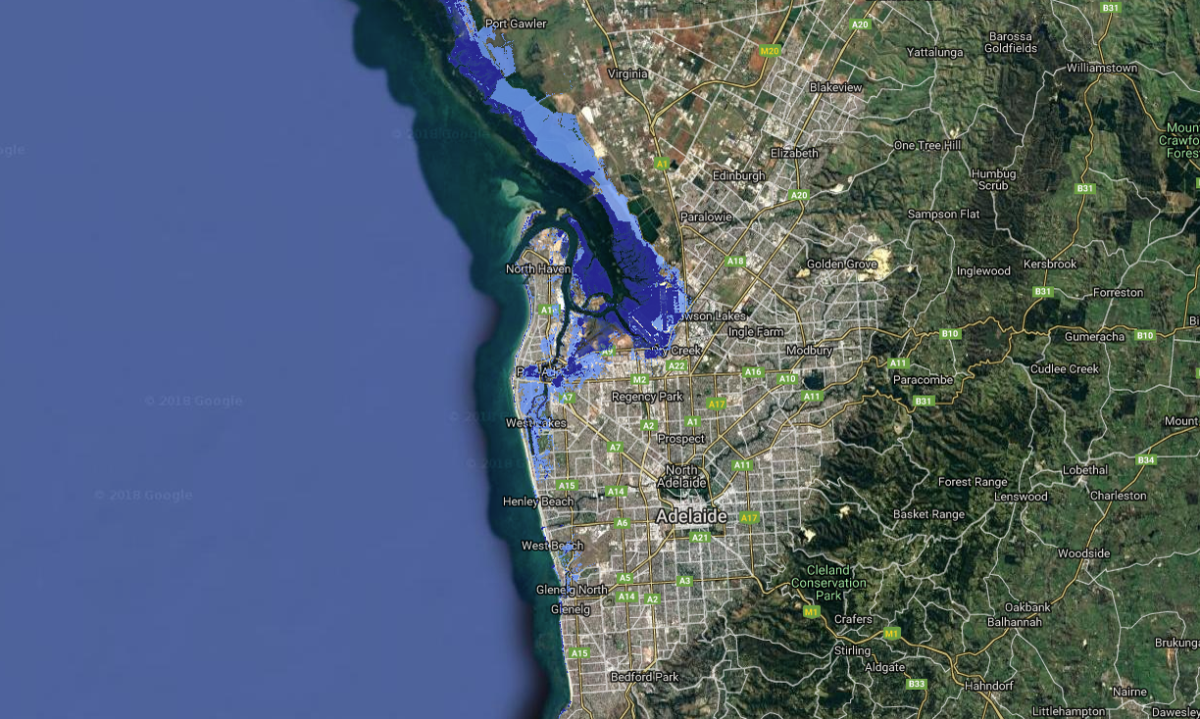

Projected highest-tide levels by 2100. Map: NGIS / Coastal Risk Australia

University of Adelaide Professor of Planning, Jon Kellett, said water inundation has already caused havoc for properties at Middle Beach, a small coastal town north of Adelaide.

“Middle Beach is already flooding frequently and is in a sense past the point of no return,” he said.

“When you get a storm surge it floods the town and it’s happening very frequently – at least once a year.”

But Kellett said it’s not just the rural areas that will bear the brunt of climate change, with metropolitan Adelaide also set to lose “an enormous amount of investment” on the coast.

“What is incontrovertible is that we’ve got monitoring data… which shows that every year since the mid-1990s we’ve seen about three millimetres of rise in sea levels,” he said.

“It doesn’t sound like much but as the decades roll by that amounts up and when you get a storm event with a surge, places that didn’t use to get flooded will become under threat.

“In metropolitan Adelaide, I’m not just talking about the individual houses, but commercial developments, shipyards, docks, all those kinds of infrastructure.

“Eventually they will come under threat of being inundated and eroded and will become unusable.”

Kellett said the waste water treatment plant at Lonsdale is an example of a low-lying building at risk of flooding.

“Over time it will be threatened by flooding and erosion because of its low location,” he said.

“It’s releasing cleaned-up water into the sea and eventually it will have nowhere to go.

“This is something long-term – we’re talking decades, usually. But, the nature of planning is, we have to be thinking of these things now.

“There’s no use leaving it two or three years before the situation is desperate.”

It’s not just flooding that has caused problems for Adelaide’s existing infrastructure.

Long said a lack of foresight from past architects has meant most of Adelaide’s coastal properties are ill-equipped to deal with soaring temperatures.

“When you look at coastal properties it’s quite interesting because the majority of Adelaide’s coast is to the west, which receives the harshest sun,” he said.

“We’ve got a lot of properties that are facing west that are just boiling in the summer, so people are cranking the air-conditioner which is adding stress to the (energy) grid.

“That’s a chain reaction of what happens when there is bad design, but if there is more appropriate design – whether it’s shading or orientation – you reduce the need to use so much energy.”

Temperature projections for South Australia to 2090. Source: Goyder Institute

Long said past planning decisions had also impacted South Australia’s ability to effectively deal with rainwater flow.

“We need more water-sensitive design, especially given scientists say torrential rainfall will come more and we have less pervious surfaces,” he said.

“At the moment Adelaide has been engineered to just get rid of the water – get it away from the streets and roads as soon as we can – and that’s why you see all these creeks that are bordered by concrete channels to channel the water to move in one direction.

“If you have waterways which are channelling water out to the sea, that’s going to accelerate the water flow and it’s going to get it away, but what happens when there is torrential rain?

“We will have these increased surges of water and this will lead to property damage, trees will fall and we could have more landslides like what we had in the Adelaide Hills two years ago.”

According to Planning Institute of Australia state branch president, Kym Pryde, climate change adaptation has been on South Australia’s planning radar for the past 15 years, with planners now tied to strict state and local government guidelines that determine where and how buildings are constructed.

But she said while it is important for governments to enforce sound guidelines to prevent flooding or excessive heat in new builds, those policies can also create problems for developers where levels required to meet climate change projections are above already developed areas..

“We don’t want people’s houses to be subject to flooding or storm surge inundation, but it creates that problem of trying to link the old infrastructure that already exists with the new stuff that’s going to be higher,” she said.

Pryde said part of the problem with Australia’s climate change planning policies was a disconnect between different levels of government.

She said there was a tendency at all government levels for planning responses to climate change to be adopted at a “piecemeal” rate.

“You can have all the right legislation and policies in place, but if you don’t have the support from the Federal Government or the local government implementing it on the ground, then it’s really difficult to get the changes in need,” she said.

“Government policies on climate change are a bit piecemeal – they might apply to this area or that area, but it’s not a consistent thing.

“For example, when you think about local government climate change adaptation plans at a regional level, there would be councils out there in SA that haven’t done one and others that have.”

But, Pryde rated the State Government’s action on climate change adaptation highly, saying South Australia’s harsh climate might have provoked a more concerted effort for change than elsewhere in Australia.

“I certainly think that, from what I’ve seen from other states, our government has put it as a priority much more than other areas like the eastern states,” she said.

“Adelaide is not developing at the same rapid rate as Sydney, Brisbane or Melbourne, so our government actually has the time to have a think about what our future might look like.

“They’ve actually got a bit of freedom to do that, unlike in Sydney or Melbourne where there’s this pressure to keep the houses coming as they need the housing supply.”

Long agreed, saying strategies such as the Adelaide City Council and State Government’s Carbon Neutral Adelaide program, which aims for Adelaide to be one of the world’s first carbon neutral cities by 2025, and the State Government’s “30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide”, which outlines targets for Adelaide to become more “liveable, competitive and sustainable”, set a benchmark for the rest of Australia.

“Once the State Government got together a couple of years ago and made those statements about wanting to be carbon neutral that lit a fire in terms of what is the identity of Adelaide,” he said.

“I view Carbon Neutral Adelaide as an entrenched identity for South Australia because now it is viewed as a worldwide marketing tool.

“I think there is this perception among people in Adelaide that the city is third-tier and that we aren’t up there as one of the world leaders on anything, but when you look at just how much we’ve done on waste, on energy, we continue to improve on water, we are setting an example.”

According to Long, the challenge lies in convincing homebuilders to take up sustainability measures when designing their houses.

He said while incorporating measures such as better insulation and solar panels is now considered “best practice” in the construction industry, he said the public is still swayed by an “unfortunate financial view” that sustainability costs extra.

“A lot of professionals in the built environment know that sustainability is an important component and that there are more and more arguments suggesting that it should be part of building,” he said.

“However, if the client – who technically is your boss – think that they are not gaining anything financially, then they can axe anything and leave the planner in an awkward situation.

“You have to take a longer snapshot – you might be investing $15,000 on solar panels right now, but over a certain time you might be saving $100,000.”

Pryde said more education was needed to ensure clients understood the implications of their design choices.

“We can help people by providing a really good house that’s climate change ready, but when the market wants what the market wants, that makes it really difficult for planners,” she said.

“It’s important to translate some of the planners’ understanding to the community so that when they decide what kind of house they want, what materials they’re going to use, what site coverage they’re going to have, they actually understand the implications of that.”