SA’s big new solar plant: key questions answered

What is a solar thermal power plant? How does it work? How will its output compare to other South Australian generators? Will it bring down power prices? Ketan Joshi answers your questions.

The glowing central column of a SolarReserve power plant. Supplied image

Some really exciting news – a new concentrating solar thermal (CSP) plant has been announced for the town of Port Augusta. SolarReserve won a tender to meet the electricity demand requirements of the SA government and it’s relatively surprising news – though solar thermal has been more expensive than solar PV in the past, this seems relatively cheap, and it’s also a perfect fit for a community that’s been campaigning for solar thermal for many years now.

Here are your pressing questions, answered below.

What is it?

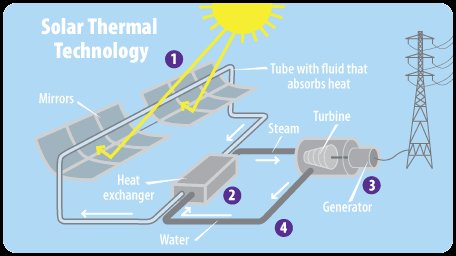

Solar thermal uses a collection of mirrors to concentrate the sun’s heat on pipes filled with water. That water turns into steam, and that steam turns a turbine – the same sort of steam-powered spinning turbine you see in a gas-fired power station or coal-fired power station.

Source: EPA

Concentrating solar thermal is slightly different – the mirrors are pointed at a single tower collector in the middle of a field of those mirrors. In addition to that, this plant will use molten salt to store energy. The mirrors direct heat to the top of a 227m tall tower, which then heats molten salt to 565°C. This molten salt can then be used to heat water into steam, which then powers the turbine.

Has anyone else built it already?

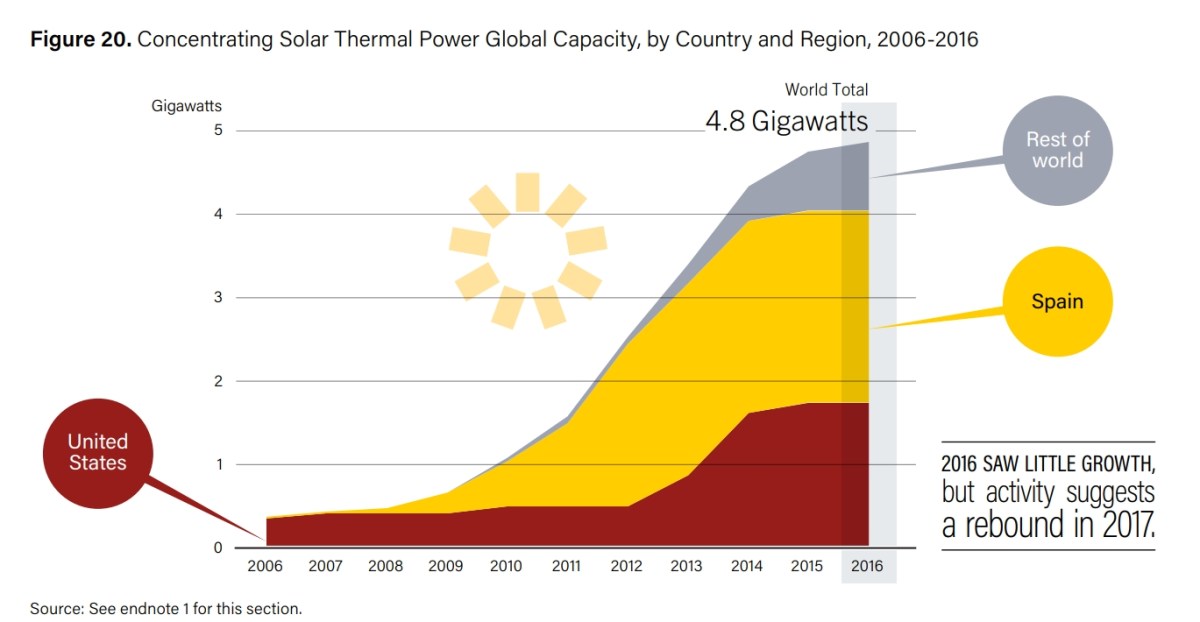

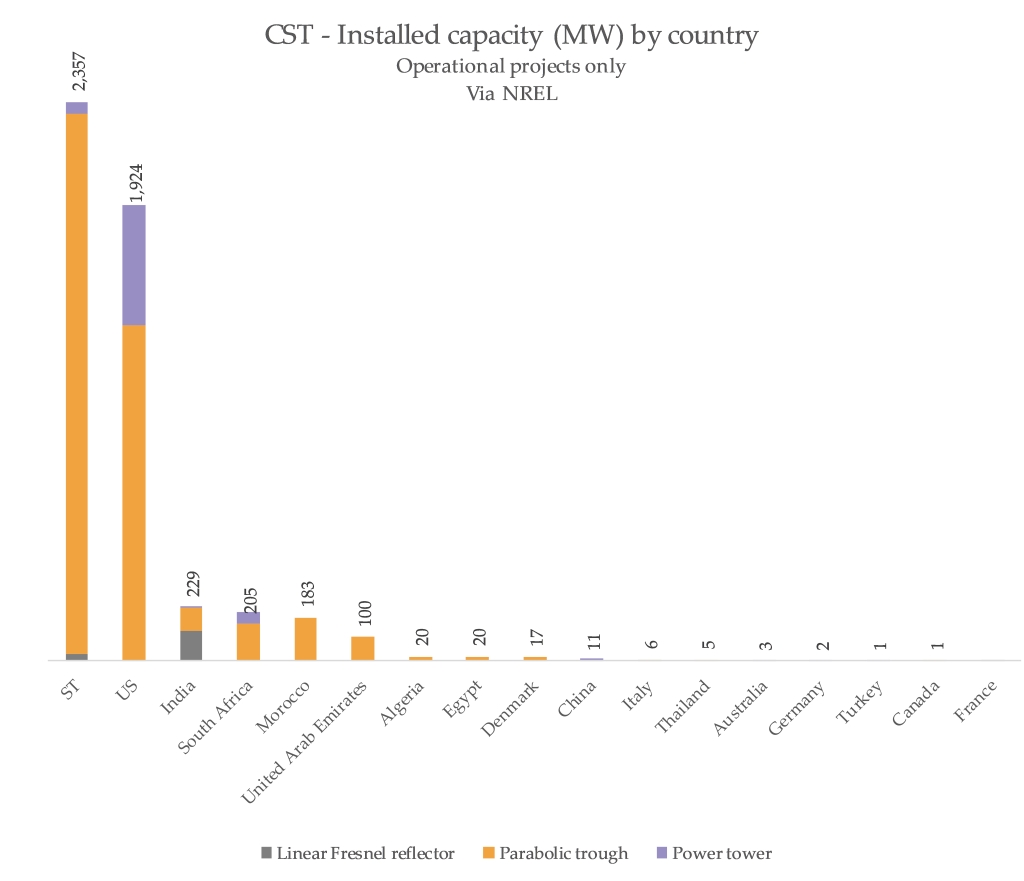

CSP is a relatively immature renewable energy technology – currently, there are 4.8 gigawatts of it installed around the world, compared to 487 gigawatts of wind and 303 gigawatts of solar PV. South Africa was the top investor in this tech in 2016, followed by China, and in terms of raw CSP capacity, Spain has the most, follow by the US (check out NREL’s project listing here). For more detail, here are some charts from the REN21 global renewables report in 2016:

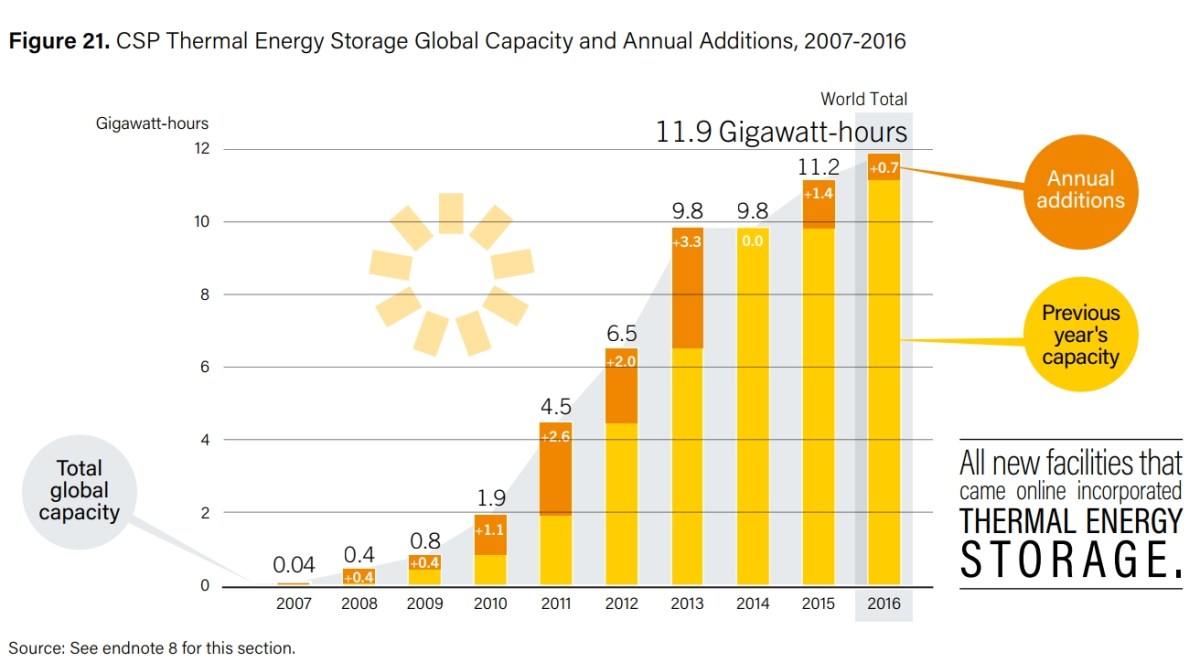

CSP has fallen a little behind, but what it lacks in cost advantages it makes up for with the inclusion of thermal energy storage – something which definitely gives it a serious edge in South Australia’s grid. (There’s a great map of CSP projects on the New Energy Update site, but details require a subscription.)

As a domestic snapshot, Australia already has some concentrating solar thermal. Liddell power station features a nine megawatt field of mirrors:

And here’s the CSIRO’s Newcastle solar field, which they used for a supercritical (that’s water as hot as it gets in fossil fuelled power stations) steam breakthrough in 2014 (the tech has also been exported to China):

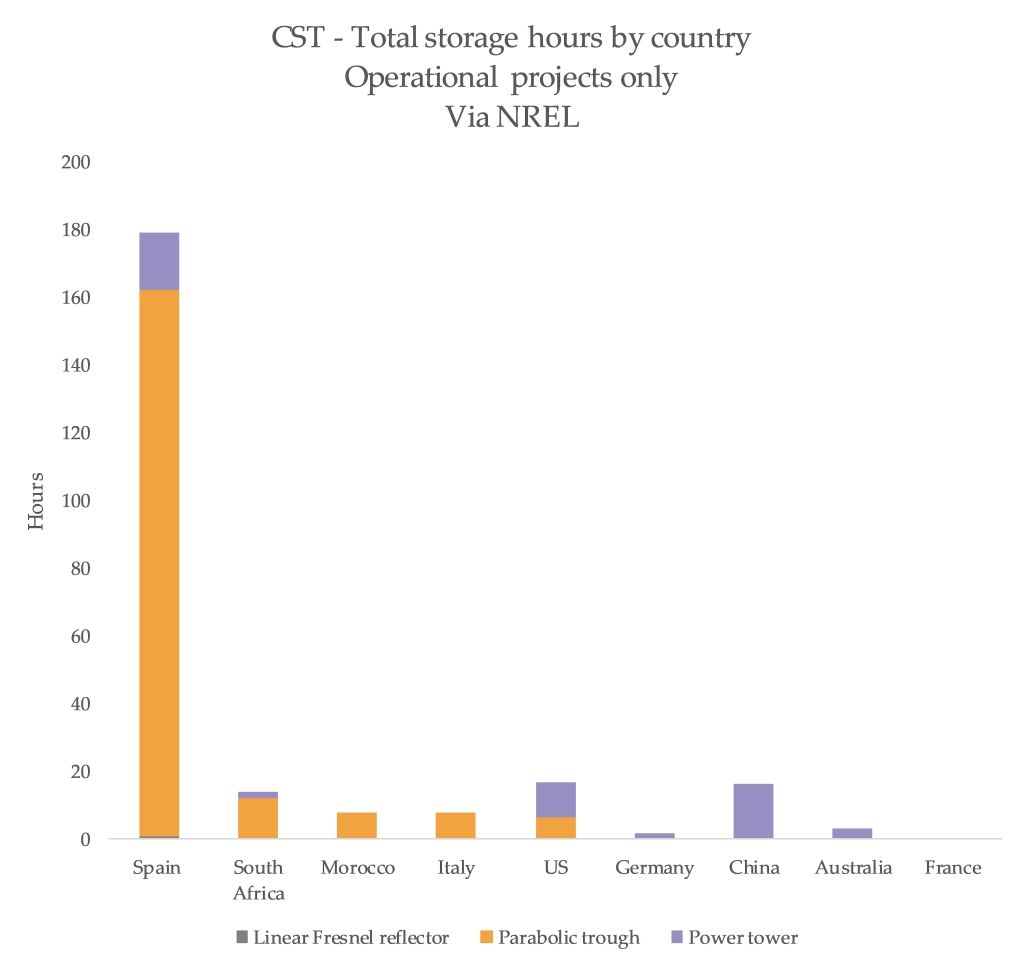

Finally, here’s NREL’s summary of total hours of CSP storage existing around the world and installed capacity, for which I used their downloadable CSP database file (operational projects only):

Why is South Australia building it?

In September 2016, soon after a state-wide blackout, the SA government began a tendering process for 75% of its long-term power supply. This plant has been built as part of that plan, but also slots into the SA government’s plan to source a total of 25% of the state’s total electricity generation from “dispatchable renewable energy”.

How big is it?

It can generate up to 150 megawatts of power at any point in time, but it will spend most of the time generating around 125 – 135 megawatts (SA Government demand). It will be able to store ~1,100 megawatt hours of energy (at 135 megawatts of output, that will last eight hours and eight minutes).

One important nuance, via Gizmodo: “One of the big challenges for solar thermal as a storage tool is that it can only store heat. If there is an excess of electricity in the system because the wind is blowing strong, it cannot efficiently use it to store electrical power to shift the energy to times of shortage, unlike batteries and pumped hydro.”

Alright, how big is that compared to that battery I heard about?

Tesla’s big lithium-ion battery to be built in the state’s mid-north is set to be 129 megawatt hours – about eight times smaller in terms of storage. But the highest possible output of Tesla’s battery is 100 megawatts – two thirds of this solar plant. This demonstrates two very different functions – Tesla’s battery can quickly fill a big gap, responding rapidly because it’s a battery, but can’t sustain its output for long. The solar thermal plant is more of a traditional generator, with molten salt storage there to firm the output of the plant as the sun rises and sets.

Sure, that sounds great, but is this really baseload?

Not quite, but that’s a good thing. “Baseload” is a euphemism for inflexible – plants that are physically incapable of ramping at a high rate, in the same way that solar, wind, gas and batteries can. The physical characteristics of this plant will likely be quite flexible, and the output will be more dispatchable than a standard solar PV plant – though keep in mind it’s still a rotating turbine, so there are limitations.

How much will it cost?

Solar Reserve, the manufacturers, have signed a ‘Generation Project Agreement’ (GPA) with the South Australian government. Jay Weatherill told me on Twitter that: “We expect to pay $75/MWh levelised cost for duration of contract capped at $78/MWh”. (I’m pretty sure this excludes the additional payment the CSP plant would get from the granting of large-scale generation certificates under the renewable energy target – another ~$40-60 per megawatt hour). The South Australian government says this was the lowest cost option of shortlisted bids for the project. Via Gizmodo:

“The reported contract price to the state government of $78 per MWh is not much higher than recent contract wind generation prices and at or below prices for electricity from current solar photovoltaic power stations, neither of which include energy storage. It is also well below the estimated cost of any new coal fired power station in Australia”

It will cost $650 million to build, and will receive a $110m concessional equity loan from the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC), as announced earlier in the year.

As the REN21 report says: “While CSP remains more expensive than wind power and solar PV on a pure generating cost basis, the overall value of CSP with TES can be higher as a result of its ability to dispatch power during periods of peak demand.”

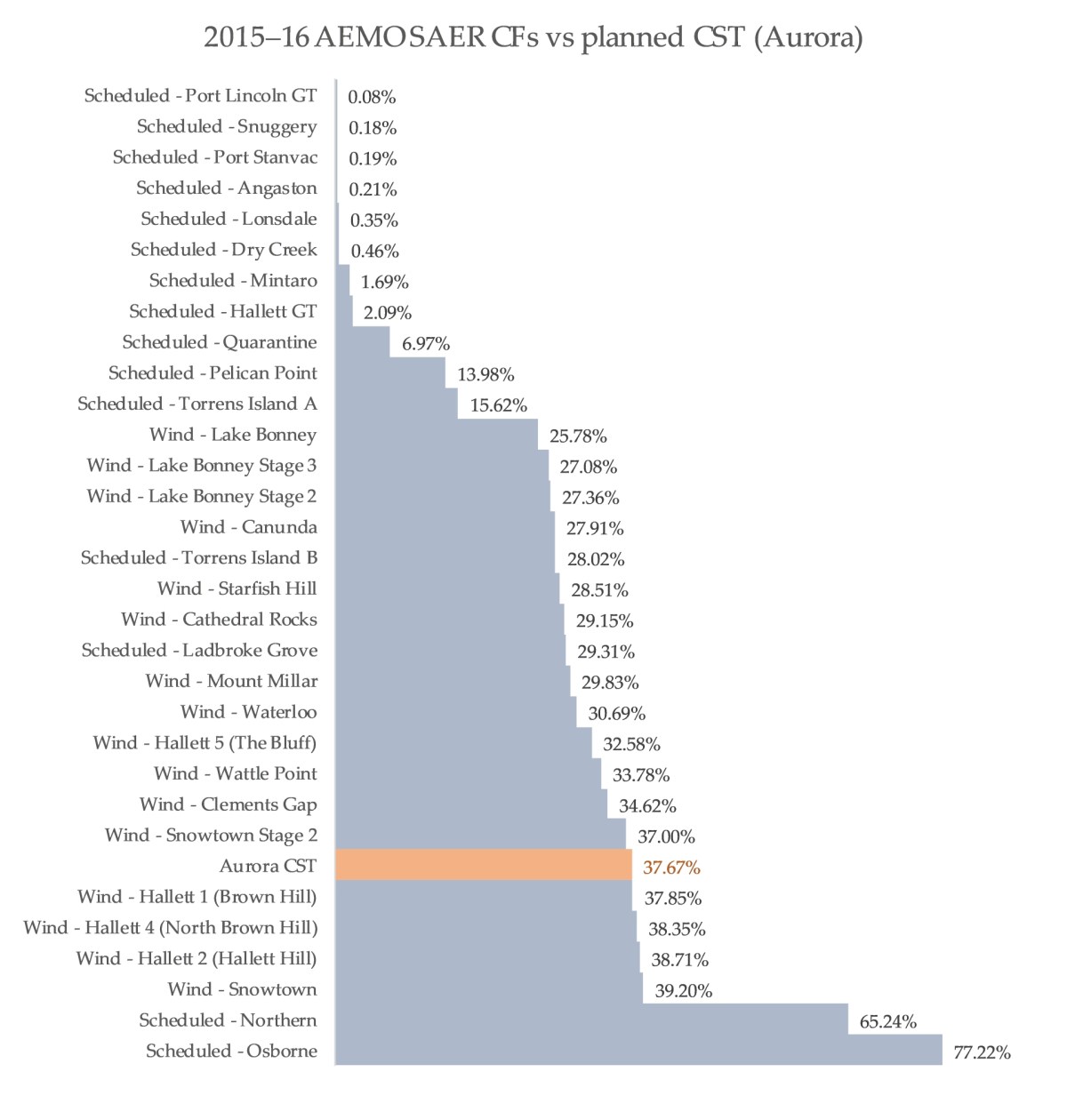

What’s the capacity factor, compared to wind and solar?

As per Solar Reserve’s website, it’ll generate 495 gigawatt hours in a year. That’s a capacity factor of around 38%. Wind in FY16 in SA was 33%. The chart below shows the forecast capacity factor of the plant compared to SA’s other generators (from SA’s 2016 AEMO electricity report):

Will this save South Australia’s grid?

Will this save South Australia’s grid?

That’s the wrong question, and a strange precedent – if you’re hoping a single addition will resolve several hundred unique, complex, interconnected issues across several states, you’re set to be disappointed.

Just like SA’s new battery announcement, this will serve a specific purpose. Most interestingly, this plant will use a spinning turbine – which is in itself a form of energy storage.

When the rotating mass of a turbine spins, it’s going to keep spinning, even if you stop the flow of steam that’s making it spin. Similarly, increasing the rate at which it spins can be done quite quickly, because it already has the ‘stored’ energy of the mass of metal that’s rotating quite quickly. This is why a collection of thermal power stations can be used to arrest rapid changes in frequency – and the core issue of concern around South Australia’s current mix.

In addition to the simple provision of energy when it’s needed, this plant will also be able to help with grid stabilisation and frequency control. This is a pretty good thing.

Okay, but will it make power bills lower?

My bet: yes, almost certainly.

More competition in SA’s relatively non-diverse collection of gas, wind and flow from Victoria will shift the bid stack and, hopefully, result in price outcomes that end a little lower than situations where gas is setting a very high price, very regularly.

Ketan Joshi is a freelance communications consultant and energy writer based in Sydney, with government and NGO clients.

Twitter: @KetanJ0