Detained children locked in cells with junk food

UPDATED: An ongoing staff shortage at Adelaide’s youth detention centre has led to children being locked alone in their rooms for extended periods, eating fast food or microwaved dinners on the floor or on their beds, the centre’s watchdog says.

Image: Tom Aldahn/InDaily

In her first annual report tabled in parliament, Training Centre Visitor Shona Reid revealed an estimated 80 per cent of day shifts went understaffed at the Kurlana Tapa youth detention centre at Cavan in Adelaide’s north during Term 1.

On average, nine out of 21 required workers were not rostered on those 7am to 11pm shifts.

Reid described the situation as a “staffing crisis” that had led to children being locked in their rooms for extended periods.

She claimed that on most nights last financial year, children were forced to eat dinner alone while locked in their rooms instead of in communal dining areas – a requirement which she said was “initially rationalised” to minimise risk of children being infected during the COVID pandemic.

But the Department for Human Services said children only ate in their room for six months from December 26 last year, with that requirement brought in following SA Health advice to reduce the risk of children becoming infected with COVID-19.

According to Reid’s report, workers attempted to “appease or placate” isolated children by giving them fast-food dinners.

The Department said the centre would occasionally hold a “pizza night” to keep children’s spirits up during the pandemic.

Reid also wrote that children reported being given microwave meals that were not always properly thawed – a claim the department denied.

“Detainees eat either on the floor or their beds,” Reid wrote.

“Disordered eating behaviours were noted, for example through some children and young people stocking up on available snack foods in case the dinner was not edible.”

InDaily first reported concerns about staffing levels at Kurlana Tapa in July 2020 following a decision to join the girls’ and boys’ campuses.

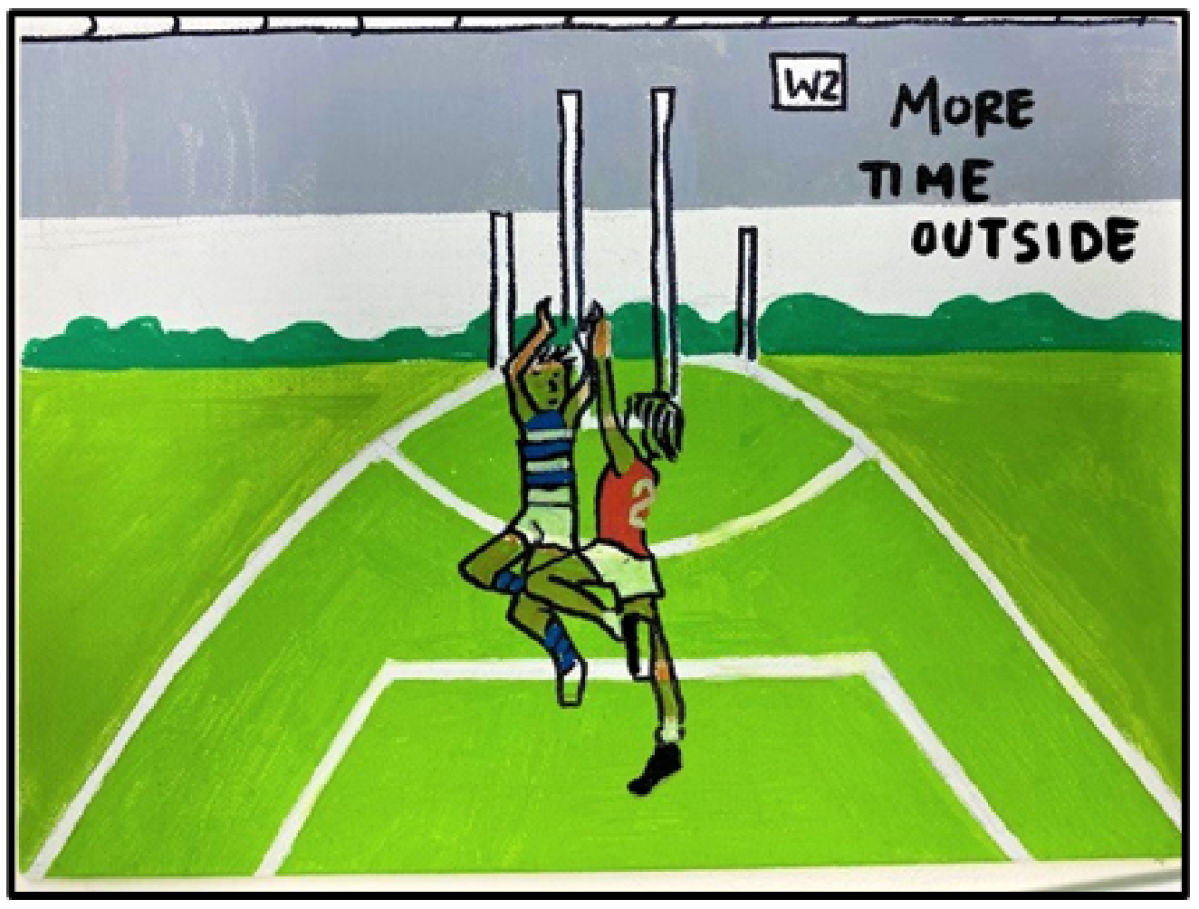

An artwork by a child detained at Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre. Image: Supplied by the SA Training Centre Visitor

Since then, the Public Service Association and Office of the Training Centre Visitor have repeatedly raised alarm about the staffing situation.

In an opinion piece published in InDaily on her final day in office, Reid’s predecessor Penny Wright described the situation as “an emergency for the future of our most vulnerable young people”.

Reid wrote that on most days in Term 1 this year, Kurlana Tapa did not have sufficient staff to run the centre “in accordance with ordinary regimes and routines”.

She found that the number of incidents of children self-harming or at risk of self-harming doubled, to a point where her office believed that nearly two in five incidents at the centre involved a young person who self-harmed or was at risk of doing so.

“I have serious concern for the young people in Kurlana Tapa, who told us that most of their time in the centre was spent locked in rooms with limited rehabilitative support or access to recreation,” she said.

“I acknowledge that operating and managing a service and care model in a youth detention centre is complex and challenging, but as a community we expect better than this.

“Vulnerable, isolated, lonely and often traumatised children and young people deserve better.”

An artwork by a child detained at Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre. Image: Supplied by the SA Training Centre Visitor

According to Reid, the staff shortage had resulted in some young people skipping medical appointments.

She said her office was aware of at least two children who repeatedly missed specialised appointments due to staff shortages and communication “failures” between health and centre staff.

Reid also reiterated concerns that staff shortages or rostering problems often led to classes run at the Kurlana Tapa school being delayed or cancelled.

“It is hard to reconcile this systemic breakdown in access to education with the attendance requirements established in the Education and Children’s Services Act 2019,” she wrote.

“The (Training Centre Visitor office) monitored detainee access to education and found that if young people could not attend, they simply missed school, in some instances for consecutive days.”

Kurlana Tapa currently employs 160 full-time equivalent staff.

So far this financial year, 13 staff, including a senior manager, have been recruited, on top of 29 staff recruited last financial year.

It’s staggering that the State Government is spending $3,828 per incarcerated young person per day but is failing to provide timely health care, education or deliver programs

Human Services Minister Nat Cook said the government needed to attract the right people to work in youth justice with the “ultimate aim of breaking the cycle of recidivism”.

“Having had close personal experience, youth justice is a priority for me,” she said.

“This government is forward looking and knows that our young people are the future of our community.

“I’ve visited the Centre three times since March and acknowledge the extraordinary work of frontline staff who provide a safe environment for children and young people in challenging circumstances. COVID-19 heightened these challenges.

“The wellbeing and safety of young people is at the heart of caring for young people who find themselves in the youth justice system”.

But Youth Affairs Council of SA CEO Anne Bainbridge said Reid’s report confirmed that Kurlana Tapa was “far from a safe or therapeutic environment for the children and young people detained and does not provide even the most basic support for rehabilitation and reintegration”.

“The effects of being confined and isolated and denied access to services and support can be seen in the rates of self-harm which have more than quadrupled since 2018-19,” she said.

“It’s staggering that the State Government is spending $3,828 per incarcerated young person per day but is failing to provide timely health care, education or deliver programs.

“The report demonstrates the government has fundamentally failed to meet its obligations to the Youth Justice Administration Act, the Charter of Rights for Youths Detained in Training Centres, or our international rights instruments and confirms that detention is expensive, ineffective, and harmful.”

A “cultural trail” at Kurlana Tapa Youth Training Centre. Photo: Supplied

Cook said Kurlana Tapa management followed advice from SA Health’s Communicable Disease Control Branch about how to best reduce the risk of a COVID-19 outbreak.

She said the Department for Human Services was pursuing “innovative programs” to make the centre a more therapeutic facility for children and young people, with an “enhanced support team” comprising allied health professionals introduced last financial year to respond to children at the centre with significant behaviours of concern.

She also reiterated that a $21.75 million upgrade of the centre was currently underway.

Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre is the only youth detention centre in South Australia, housing children aged as young as 10 who receive a custodial sentence.

Reid’s report states the number of children admitted to the centre increased by just over 14 per cent in 2021-22 compared with the previous financial year.

But Cook said that overall, the number of children and young people in custody in South Australia was on a downward trend.

On an average day, Aboriginal children accounted for more than half of all residents at the centre in 2021-22.

Reid’s report noted that young detainees aged 10 to 13 now maade up 17.8 per cent of the centre’s population.

Children in that age bracket were on average admitted to the centre more than three times each year – a “significant increase” on the year before.

Reid’s report comes amid a debate to raise the criminal age from 10 to 14, with Greens MLC Robert Simms reintroducing a private member’s bill to the upper house earlier this year.

If passed, the legislation would release all children aged under 14 from detention within a month.

Bainbridge said Reid’s report highlighted the importance of raising the age of criminal responsibility and investing in “community-led solutions”.

“Jail doesn’t help – it harms,” she said.