Calls for ‘safety net’ to tackle SA chronic disease

South Australia needs to invest more in preventative health measures rather than crisis fixes in order to manage rising levels of chronic disease, experts argue, following confirmation the state is the sickest in mainland Australia.

Image: Tom Aldahn/InDaily

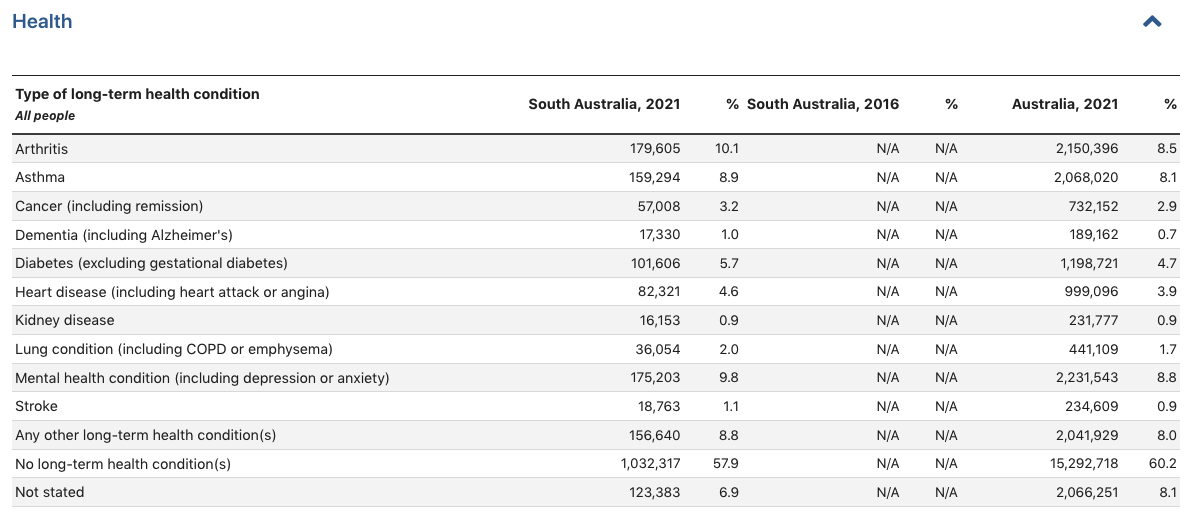

Census data released yesterday by the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveals for the first time how states and territories compare when it comes to long-term health conditions such as asthma, cancer, heart disease, mental ill health, diabetes and stroke.

The data shows South Australia is the sickest of the mainland states, with 42.1 per cent of respondents reporting at least one long-term medical condition.

The South Australian percentage is above the national average and higher than any other mainland state.

University of Adelaide Stretton Health Equity director Professor Fran Baum told InDaily it was unsurprising that South Australia was the sickest mainland state, given it also had the oldest population.

Baum said other “social determinants of health” such as housing and stable employment had also been on the downward trend in South Australia, meaning there was a greater likelihood that people would develop long-term health conditions.

“We do have an older population than most of the other states probably except for Tasmania and those long-term chronic conditions tend to come on as you get older, so that’s probably part of the story,” she said.

“We also know in that time housing has got more difficult in South Australia, jobs have become more casualised, the state education system isn’t as strong as it was.

“All the social determinants of health in South Australia aren’t as strong as they used to be.”

Courtesy ABS

Adelaide GP Dr Rod Pearce, a former SA president of the Australian Medical Association, said there needed to be greater emphasis on prevention and management of chronic conditions.

“Medicare doesn’t pay for preventative disease, it pays for disease,” he said.

He noted a third of Australians were estimated to have “multi-morbidity”, with data showing up to 80 per cent of those aged 65 and over suffering from three or more chronic conditions.

“As you get older, healthy ageing is about managing those conditions – it’s not about concentrating on the individual diseases and acute management, it’s actually about preventing those diseases from inhibiting your lifestyle,” he said.

“We need to be on top of keeping people out of hospital rather than waiting till they’re in, you need to concentrate on the whole person not on the individual diseases.

“What general practice talks about is the need for the safety net at the top of the hill rather than the ambulance for the crash at the bottom of the hill.”

The Census data shows South Australia had a higher percentage than the national average for every long-term health condition except for kidney disease, which was on par with the national figure.

Mental health conditions were listed among the most common health problems, with 175,203 people – or 9.8 per cent of the SA population – reporting they lived with depression or anxiety.

That is above the national average of 8.8 per cent.

Mental Health Coalition of SA executive director Geoff Harris said while it was not clear whether mental health conditions were on the rise in South Australia, the figures proved that the government needed to invest more in long-term supports.

“The key thing here is it’s talking about long-term conditions and so that’s conditions that people are managing over a long period,” he said.

“A lot of the state investments in mental health are short-term episodes of care and the bit that’s still missing is the longer-term support to get back in the community and rebuild your life.

“I think it’s those supports around housing, employment, relationships, which require a bit more longer-term support that’s different from crisis support to get you through an acute episode of illness.”

Baum suggested the state government reintroduce community health centres, which were popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a means of preventing chronic health conditions.

She said the government-funded centres housed health professionals such as GPs, social workers and nutritionists, and ran courses on topics such as parenting, dealing with domestic violence and healthy eating.

“They were local, often with a local management committee, and they would support people in all sorts of ways, both to deal with chronic illness, which in turn would keep people out of hospital, but also to prevent it in the first place,” she said.

“They don’t seem important on their own, but when you put them together, they have a population health-wide effect of keeping the population healthier and, of course, they’re much cheaper than hospitals.

“I think it’s such a shame that we have – and I think they’re part of the reason why we have – increasing chronic disease.”

Baum said while experts argued preventative health measures were needed, often governments were reluctant to provide funding.

“It’s such a tricky thing because what you’re saying to a government is you’ve got to invest in measures now to prevent problems in the future, but that’s probably beyond their electoral cycle,” she said.

“Promising hospital beds is probably a much more politically appealing thing to do than to say, ‘we’re going to prevent health problems that will show itself in a generation or so’.”

Health Minister Chris Picton said it was “obviously worrying” that South Australia has higher rates of chronic conditions than other states.

“It does highlight the challenge that we have,” he said.

“We know other states are facing significant health challenges as well but when you look at those sorts of statistics it does highlight that challenge.”

Picton said he was “really passionate” about improving preventative health and stopping people ending up in hospital.

“That’s a very long-term challenge to deal with but I think it’s well worth taking on because the more we can do to keep people out of hospital in the long-term the less pressure and ultimately the less cost,” he said.

Picton said it was a key area for the State Government across multiple portfolios “because a lot of the factors that lead to people’s chronic conditions are not just the health system alone”.

“Clearly the social determinants of health can be somebody’s employment status, can be somebody’s income, their education level, their housing – a whole range of barriers that people have in life impact their health as well,” he said.

“So a lot of our commitments in other areas impact upon people’s health outcomes as well whether it’s building more public housing, creating more jobs, that all helps as well.”