The boy who didn’t matter

Seven months before George Duncan was drowned in the Torrens, a young man died near the same location in a way which has troubling echoes of the later crime. Simon Royal explains why 50 years on the teenager’s family still search for answers and want the official death verdict re-examined.

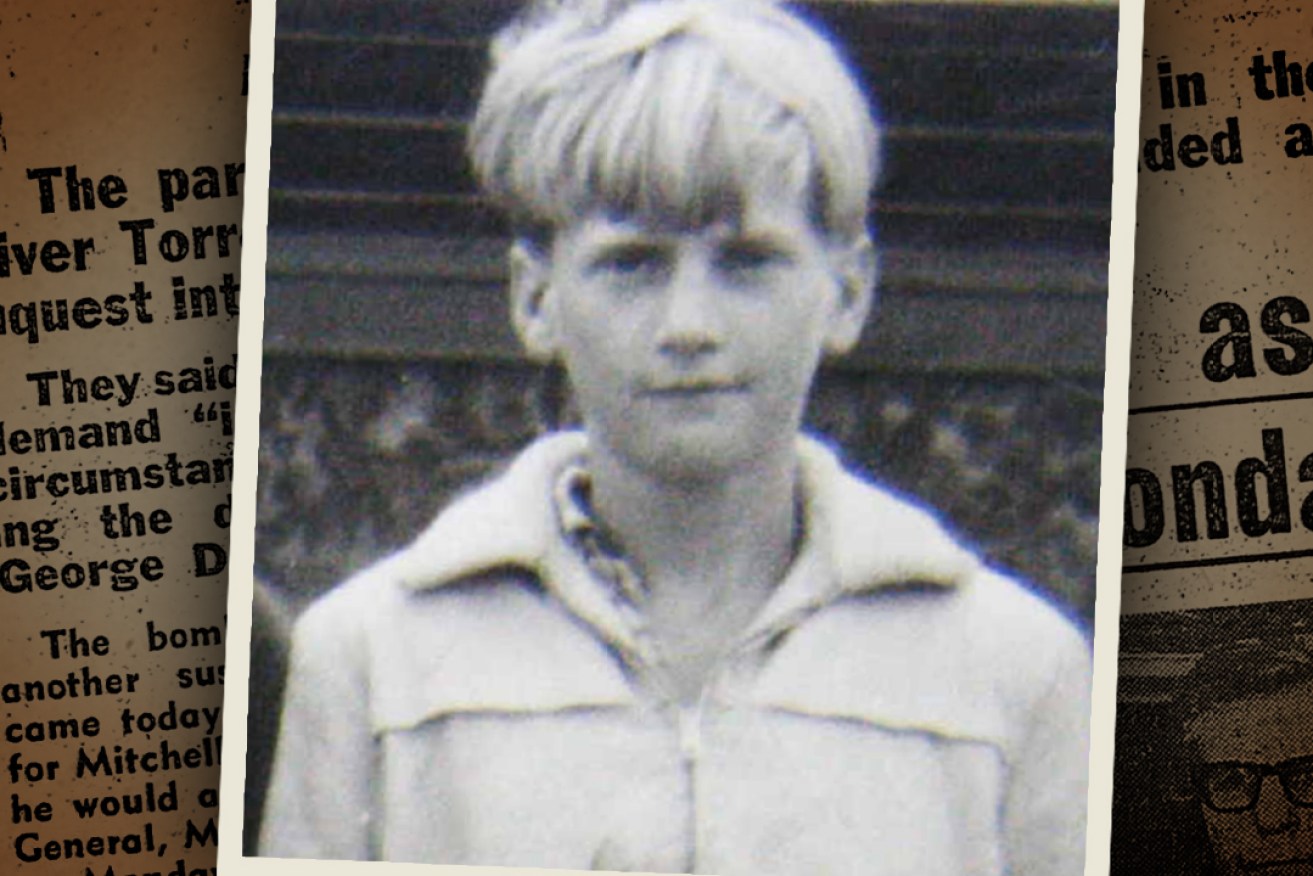

Wayne Craill, pictured here as a primary school student, was found in the Torrens in 1971. The 19-year-old's death was recorded as misadventure and drowning and he was cremated before test results revealed a puzzlingly high level of alcohol in his blood. Photo supplied.

Thursday October 28, 1971

Dr Philip Kuchel had expected the bloated green face, with its opaque unseeing eyes, when the charge sister told him to sign a death certificate for a body police had just fished from the River Torrens.

What the young Royal Adelaide Hospital registrar hadn’t anticipated was the smell. It clawed like a living thing at his clothing, his throat, his nostrils. That high, ripe reek of death stayed with Dr Kuchel for the rest of his shift. The memory of it has stuck for more than 50 years.

“It hit you as soon as they opened the van doors”, the now Emeritus Professor Kuchel recalled.

“I think it was the first death certificate that I was responsible for signing. I was 25, and a first-year resident.”

“I have very clear images of particular patients from that time, and of this incident, which was something out of the ordinary.”

Dr Kuchel remembers he thought it strange that the body which had been in the water for days should be missing a single boot: “Why one and not the other?” he asked himself.

Like the smell, other things have lingered with Philip Kuchel from that day – things said to him about who the person was in life.

“My impression was that he was a down and outer,” he said.

“I got that from the two gentlemen who brought him in in this van. The impression was that the person was a derelict who had fallen into the water, drunk. But I’ve always wondered about him, who he was.”

But the boy – a young man, really – was not a drunk. His father said his son didn’t like beer at all and didn’t fit the hard-drinking culture of the 70s. Even his friends, who had shared the occasional drink with him, insist they’d never seen him drunk. The boy wasn’t a derelict, either. He lived in a neat cream brick home, not far from the Chrysler factory in Adelaide’s southern suburbs. He had a job which he liked – an apprentice spray painter – and a family and friends who loved him.

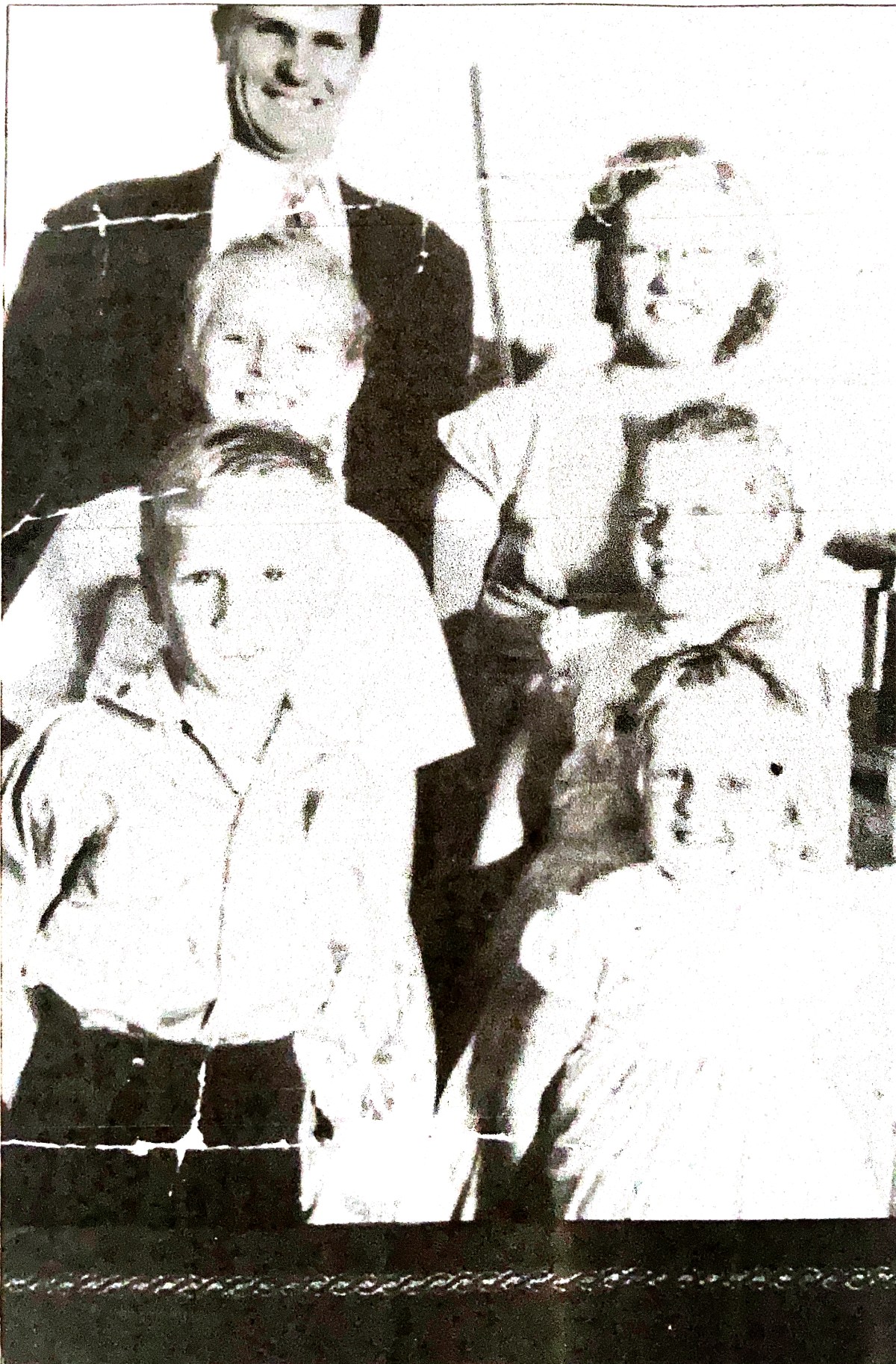

Wayne Craill, bottom left, with his father, mother and four sisters. Photo supplied

His name was Wayne Garth Craill. He was barely past his 19th birthday when he drowned in the Torrens, late at night, on October 22nd, 1971.

The remarks made to Dr Philip Kuchel about Craill were the first sign the apprentice was poised to slip through the cracks of the coronial system. A litany of factors contributed to the young man’s fall. Experts being misled by the very same experience that informs their expertise. The raw workings of class; he was a long-haired working-class kid – an apprentice without powerful advocates for his cause.

Unreliable science, and even the Craill family itself, unwittingly contributed, too. But arguably, fear also played a part. It stopped witnesses to Wayne’s last hours from fully sharing their stories. It may even have held the authorities themselves in check.

Friday October 22, 1971

Wayne Craill’s last day alive was cold, grey and miserable. Normally, the 19-year-old detested that sort of weather but his sister, Susan Cameron, recalls her brother was too excited that day to care. Elton John was playing at Memorial Drive, and though Creedence Clearwater Revival was more Wayne’s thing, he and two mates planned to see the British superstar after work.

“Oh yes, he was looking forward to the evening, he was very interested in music,” Susan Cameron said.

“He and a few friends had a band going. What I remember best is that he liked playing his guitar and listening to Creedence Clearwater Revival.”

“Wayne was very quiet in his ways, he kept to himself a bit but he was my big brother and he looked out for me. He enjoyed the company of his friends. He was just a normal 19 year old kid.”

Susan Cameron was 17 on the evening her brother walked out the front door for the last time.

“I remember being asked to go with him, if I wanted to go to the concert, and I said no. So I didn’t go … unfortunately,” she said.

Wayne Craill’s sister Susan Cameron at the Torrens near where her brother’s body was found in 1971. Photo: Simon Royal

Wayne’s friends, Mitch Rowden and Charlie Taylor, arrived in Mitch’s FB Holden station wagon at about 7pm. On the drive in to the city, the trio stopped at the Marion pub to buy three bottles of beer. They stopped again in the city to give a lift to two teenage girls they knew, Gail Crabtree and Anne Noble. In his court statement, Mitch Rowden said only one bottle of beer was opened and shared. He didn’t specify whether Wayne had any.

Once at Memorial Drive, Mitch and Charlie discovered they didn’t have enough money for a ticket. They went off to the Lord Melbourne pub, while Wayne and the girls went into the concert. An arrangement was made to meet Wayne out the front afterwards.

When Elton John finally walked offstage at 10.30pm, wearing a “white ten-gallon hat, Bermuda shorts… and winged boots” there was no sign of Mitch and Charlie. Anne and Gail rushed to catch the last bus home to Elizabeth. As they left, Wayne said he’d wait for his mates to turn up. It was close to 11pm on an unseasonably cold and wet night. It was the last known time anyone saw Wayne alive.

For the next week Ted Craill, Wayne’s father, searched for his son. Wayne’s friends helped too, asking around about him in the city. Ted made repeated visits to the police, first to report the boy missing, and then to speak of a terrible “premonition” he’d had.

On one visit, Ted told police his son suffered from “two blackouts and was being treated … it was thought he might have a tumour”. Later though, Ted added that tests had revealed nothing and “I think the doctor said something to the effect we’d wait to see if a condition developed.” Sue Cameron says it wasn’t unusual for her parents to fret over Wayne’s health.

“They always worried he didn’t eat enough. Of course they worried, he was the only boy, their fair-haired boy,” she said.

Richard Randell and Alex Salomon revelled in their reputation as the worst rowers in the entire Scotch College team. Along with two other friends, they’d dubbed themselves “the bomb out four”.

Early Thursday afternoon, October, 28, 1971, the carefree crew had taken a boat out on the river. “We’d gone out for a cigarette, as usual. Perhaps that’s why we weren’t any good”, Randell said, chuckling at the memory.

By then Wayne’s body had been floating for six days in the lazy, languid stretch of the Torrens a few metres downstream from King William Street Bridge. The rowers discovered him near a clump of reeds.

“The thing I remember is he was on one side, with part of his chest and one shoulder out of the water,” Randell said.

“Neither of us have forgotten that day … you hardly could,” Alex Salomon added. “It’s funny, we were just talking about it last week, wondering who he was.”

“Misadventure” and misgivings

After being retrieved from the Torrens, Wayne’s body was taken to its appointment with Kuchel, and then on to West Terrace Morgue, where an autopsy was performed at 9.30 the next morning, Friday, October 29, 1971.

The pathologist, Dr J.M.Dwyer, noted “no signs of injury were found”, but the body was “extensively discoloured and distended by gas”. Aside from the missing boot, the police noted Wayne’s clothes weren’t in disarray – another sign the teenager hadn’t met with violence. In Wayne’s pleural cavities, Dwyer found “considerable transudate”, a substance that can form when water is aspirated into the lungs during drowning.

The pathologist was a bit mystified by a “pale myocardium”, but there was no indication of abnormality or disease. The cause of death was declared as “drowning”. Dwyer also took a sample of Wayne’s blood, which was sent to the Chemistry Department for analysis.

Later that afternoon, city Coroner Tom Cleland signed the pale blue burial order releasing Wayne’s remains to his family. Citing misadventure and drowning, the Coroner deemed an inquest – and further police investigation – unnecessary. Cleland added a note in blue pen about “a brain tumour which was being medically treated”. Wayne Craill was cremated at Centennial Park the following Monday, November 1, 1971.

Two days after the funeral, the results of the blood test came back. They revealed a high level of alcohol in Wayne’s blood – 0.11 per cent. This was hugely puzzling to the family, but not to the authorities. For them, the machinery that explores and explains sudden deaths had done its job. It took more than a year for the obvious question to be asked – how did a young man apparently not much given to drink, get falling-down drunk?

Apart from the customary family notices in The Advertiser, Wayne’s death didn’t rate a mention in either of the city’s two daily newspapers. In 2022, that seems astonishing. A body in the Torrens, but no press coverage, and no inquest? To the authorities in 1971, however, dealing with death on the Torrens was a relatively commonplace event. Former assistant police commissioner John Murray argues a corpse in the river wouldn’t automatically raise suspicion, “because bodies were turning up all the time then”.

“A uniform car would have been sent. A couple of detectives might have been called to look at the scene, they might have been, but it wasn’t always the case,” Murray said.

In 1971, John Murray was a rising young officer, eager to adopt the new technologies that were transforming police work. But he was also well versed in the traditional ways, explaining how police would have approached the Craill case.

“It was only [later in the 70s] that there was a level of sophistication about what we were by then calling a crime scene,” he said.

“It wasn’t even called a crime scene back in this instance of this young man. It was just, ‘someone is dead’. So there’d have been no determining of the scene and blocking it off, or putting up tape or anything like that. That wouldn’t be done. There would have been no one standing by taking each piece of evidence if you like – clothing, something found at the scene – putting it into a bag, marking it and making reference to it. No search of the river downstream…none of that would have been done.

“The thing today is that there are no assumptions made, that’s the thing – no assumptions made until the job is done.”

It took more than a year for the obvious question to be asked – how did a young man apparently not much given to drink, get falling-down drunk?

Coronial records show that most years Coroner Cleland could expect a steady workload from the Torrens; accidental drownings, as well as suicides.

News values were different, too. Three weeks after Wayne Craill’s death, a 63-year-old drowned in the river around Payneham. The unnamed man rated a brief page seven mention in the Sunday Mail. The same month Seagull the pony, and the sad tale of his demise, rated far more column space. The unfortunate creature wasn’t a Torrens victim, but rather drowned at Henley Beach. Something spooked Seagull, and after throwing his 12-year-old owner to the sand, the pony galloped into the sea, only to be washed ashore a few days later. Now that was news.

Of course, the fact Wayne’s death was treated in the standard way was no comfort to the Craill family. Susan Cameron says that from the outset, her parents felt the official reaction was “cruel” and “without compassion”.

Wayne Craill with his sisters. Photo supplied

In the silence after his son’s death, Ted Craill turned from father into investigator. It was Ted who discovered that Wayne, Mitch and Charlie had met up with the two girls. Ted also heard rumours Wayne might have gone to a party in North Adelaide, an oddly bohemian thing for a working class suburban kid to do. So many aspects of the case didn’t make sense to the family: the missing boot, the fact Wayne could swim, the alcohol.

No one seemed to listen or take Ted seriously. That is, until May 1972, when another man drowned in the Torrens. Like the apprentice spray painter, this man also died late at night, not far from where Wayne was found.

Suddenly, people began paying attention to Ted.

The Duncan drowning

Without question the drowning of gay law lecturer, Dr George Duncan, on May 10, 1972, ranks as one of the worst scandals in the history of the South Australia Police Force.

That’s hardly surprising, given suspicion quickly fell upon three vice squad officers for heaving the law lecturer into the river. In the mid-80s, two of those three officers were charged with Duncan’s manslaughter. They faced trial and were acquitted. The third man didn’t go to trial, having been found not to have a case to answer. The section of the Torrens where Duncan died was a gay beat. In 1972, male homosexuality was illegal, the law branding gay men as criminals.

In the broadest sense, the law itself set the stage for the violence that occurred on the banks of the Torrens, and, for that matter, every other gay beat around the country. Fittingly, one legacy of Duncan’s death was to galvanise SA into becoming the first Australian jurisdiction to successfully decriminalise male homosexuality.

There was a more immediate problem, though. Investigations into Duncan’s killing had stalled. Under pressure from both the University of Adelaide Law School, and parliament, the Dunstan government ordered the Coroner to hold an inquest into the academic’s death. That commenced in early June, 1972, and with it, the scandal bounded away at breakneck speed.

A memorial plaque to Dr Duncan at the Torrens. Photo: Adelaide Law School Facebook page

Most mornings brought fresh headlines in The Advertiser, such as details of lurid bruising on Duncan’s body, or allegations that police routinely harassed gay men at the Torrens. There was no respite when The News hit the stands in the afternoon.

Tensions peaked on the last day of June, after the three vice squad officers under suspicion refused CIB chief Superintendent Noel Lenton’s directive to answer the coroner’s questions about their knowledge of, and alleged involvement, in Duncan’s death. The Coroner’s transcript and The Advertiser recorded the Superintendent’s response:

“The only reasonable inference that could be drawn from this conduct is that you refused to answer because you had something to hide and this conduct can only reflect discredit on the Police Force,” Lenton said, before suspending the three officers.

It was hard to imagine how the scandal might possibly have gotten worse, but two days later – Sunday, July 2, 1972 – it did.

Craill inquest call

Normally, the Craill family didn’t stand on ceremony at breakfast time – it was every person for themselves. This Sunday, though, was different. Joan Craill, Wayne’s mother, had set the breakfast table with good things, a bowl of oranges from Ted’s garden in the centre.

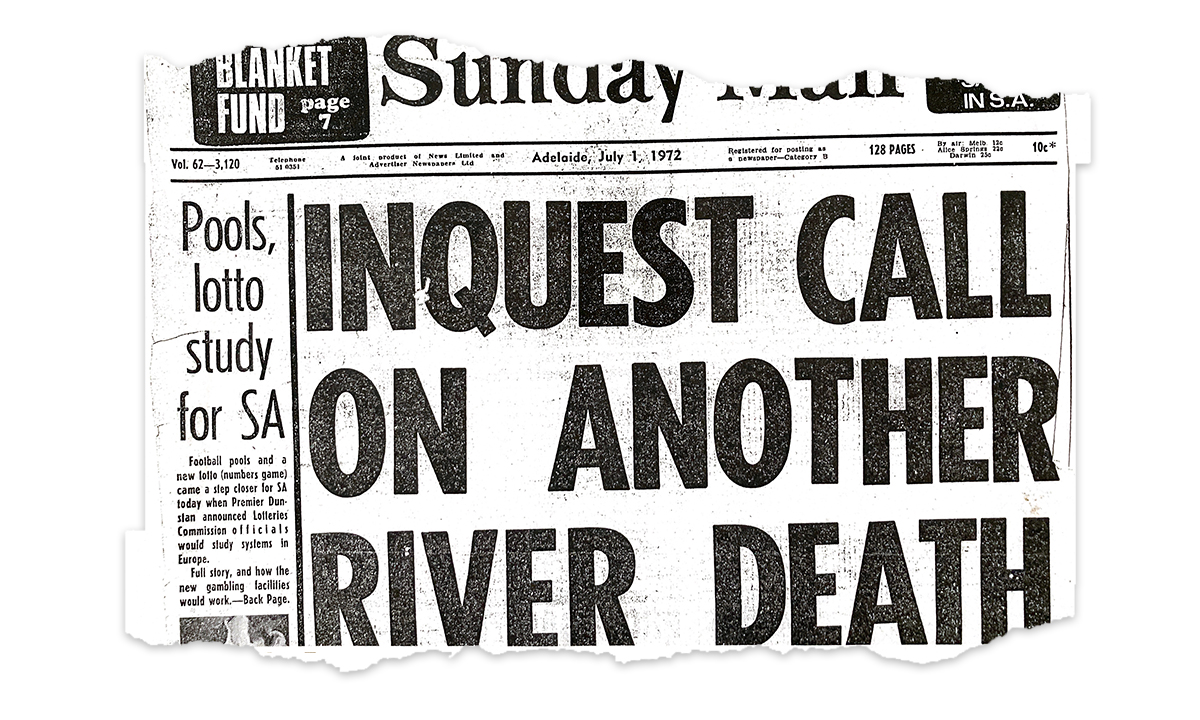

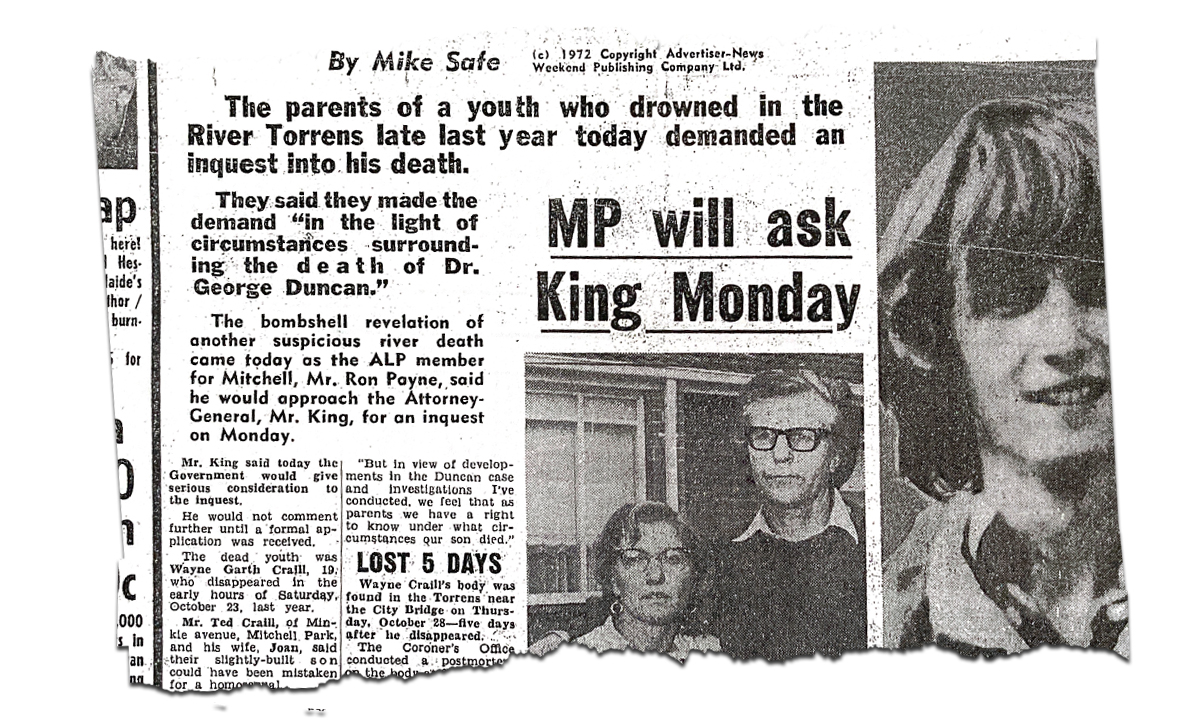

The Sunday Mail was laid out to catch her husband’s eye when he came into the room. Both Joan and Ted Craill knew what to expect, having told their story to a journalist and photographer from the paper a few days earlier. Still, after months of public silence surrounding Wayne’s death, the front page headline set them back a moment: “Inquest Call on Another River Death”.

Journalist Mike Safe drove the point home, writing it was “ a bombshell revelation of another suspicious river death”, and then quoted Ted Craill saying, “… in view of the developments in the Duncan case and investigations I’ve conducted, we feel that as parents we have a right to know under what circumstances our son died”. Often, what’s left unsaid shouts the loudest. There wasn’t the slightest suggestion of police involvement in the Craill case, yet after reading the story, the dreadful possibility is surely the first thought people would have had.

A photo of Ted and Joan featured, plus a separate one of Wayne, smiling shyly. It was the first public glimpse of a boy whose death, so far, had caused not a ripple of concern to authorities.

The Craill’s spoke of all the jagged edges which they felt didn’t fit the neat official account: the missing boot, and the abundance of alcohol which the Sunday Mail said was “the equivalent of seven and a half schooners of beer”. They added Wayne could swim. And then they went further.

In a newspaper read by hundreds of thousands of people, Ted and Joan Craill said something extraordinary for the times. They raised questions about their son’s sexuality.

“Wayne had shoulder-length hair and very soft features… Mr Craill and his wife, Joan, said their slightly-built son could have been mistaken for a homosexual.” Ted went on to assure readers that he didn’t think his son was actually gay, “as he was popular with girls and willing to mix with them”, but on the banks of the Torrens ‘mistaken’ identity might have fatal consequences.

For any parent in 1972 to publicly discuss even the possibility of a homosexual child was to invite ridicule of the nastiest kind. Hurt, confused, and deeply frustrated by the official response to their son’s death, Susan Cameron says her parents no longer cared about what other people might think.

“It’s desperation I suppose,” she said. “They were just trying to get something done, and not being afraid to say that. It wouldn’t have bothered anyone in the family anyway [had Wayne been gay] but just getting it out there and connecting it with Duncan … it was a brave thing to do, very brave.

“They felt that at last something might get done after going all that time not knowing. I think they would have had a sense of relief in knowing that it been had brought it to the attention of people.”

The newspaper article was a direct result of Ted having found an ally in his local MP Ron Payne, who backed demands for an inquest. Payne said; “It seems strange that a 19-year-old could go to a concert in the city and end up drowned in the Torrens.”

The apprentice and the academic came from very different worlds, but fusing them, in the public mind at least, was key. It made refusing an inquest into the Craill matter untenable. Indeed, Attorney General Len King, had already decided to order one: he and Ron Payne had spoken prior to the story being published.

Once the Coroner had wrapped up the Duncan inquest, without discovering the identity of the law lecturer’s killers, King wrote to him, asking his view on the Craill case. It was a courtesy of the state’s chief law officer, to which Cleland replied with a homily on the nature of inquests.

“I agree that in the circumstances an inquiry should be held,” Cleland wrote. “It has been said that the purpose of an inquest may be to dispel the mystery surrounding a death. In this case, the deceased who was said to be an abstainer had a significant amount of alcohol in his blood.”

The Coroner repeated that line to The Advertiser for an article the following day, where he also restated his view the Craill matter was a straightforward case of misadventure.

But there was nothing new about the ‘mystery’ Coroner Cleland was now proposing to solve. How “an abstainer” ended up drunk enough to topple into the Torrens was a question that should have been asked when Wayne Craill was retrieved from the river – before the Coroner permitted him to be cremated without an inquest.

November 1, 1972: Craill inquest

Thomas Erskine Cleland, the city Coroner, came from one of the most storied and well-connected families in South Australia. His father, E.E. Cleland, was a Supreme Court judge, his uncle was the first superintendent of Glenside Hospital. Cleland National Park is named for another extraordinary relative. The list of Cleland accomplishments goes on, weaving through agriculture, viticulture, medicine, and, of course, the law and public administration.

Tom Cleland was in his early fifties when the Playford government made him city Coroner in 1947. His approach to the job was thoroughly modern, using the circumstances of individual deaths to fashion recommendations that might prevent future occurrences. Cleland was an early advocate for helmets to be made compulsory for motorbike riders. After a spate of suicides amongst World War Two veterans, he pushed for better mental health services, remarking of one particularly harrowing case, “our community owes these men an obligation”. Not everyone welcomed those recommendations, but unlike his critics, Tom Cleland generally made sure his view was backed by science.

Now, after a quarter of a century in the job, as the Craill inquest opened in the same stuffy courtroom where the Duncan saga unfolded, Coroner Cleland’s faith in science would help lead him astray.

There was alcohol in Wayne Craill’s blood. Even Ted was convinced of that, telling the court: “I [have been] guided by Sgt Wiech re his alcohol and he assures me this [amount] of alcohol is enough to make his (sic) tottery and he wouldn’t [have] good control over his movements.” The clear inference being drawn is Wayne fell into the river, and was too inebriated to save himself. According to Monash University Professor of Forensic Medicine, Dr Stephen Cordner, the principal shortcoming (amongst many) of this scenario is the blood test alone can’t distinguish whether the alcohol in Wayne’s blood came from him drinking it, or from decomposition after six days in the Torrens.

“The essential answer is no, you can’t rely on this. As scientific matter you cannot rely on a blood alcohol level of point 11 in a decomposed body to conclude that person consumed alcohol,” Professor Cordner said. “You’ve got no objective, scientific way of saying, simply on the basis of that blood sample, that this represents ingestion of alcohol during life … you have to go back and look at what happened to conclude whether that person had been drinking.”

Gail Crabtree and Anne Noble were the last people known to have seen Wayne alive. Both of them told the coroner that Wayne didn’t drink at the Elton John concert, and definitely wasn’t drunk when they left him. Mitch Rowden, too, insisted his mate wasn’t drunk when he last saw him. Cleland, quite properly, accepted the evidence of Wayne’s friends. They’d arrived at the essence of the mystery Cleland said he needed to dispel – how Wayne ended up drunk.

In 1971, that was no easy task for either a committed teetotaller or a determined drunkard. The pubs closed at 10pm. Just where, at close to 11pm, did a kid on an apprentice’s modest wage, who didn’t drink much, who didn’t have a car, manage to find enough booze to get so staggeringly drunk he fell into the river and drowned?

More baffling than the logistics of that proposition, is the fact Cleland didn’t ask a single question to discover how it might have come to pass. Nor, in the police reports to the inquest, is there evidence of an attempt by SAPOL to track down the source of the alcohol. To be fair though, the original decision not to hold an inquest meant those inquiries started 10 months after the fact. The Coroner made no comment, and showed neither curiosity, nor concern, over the obvious inconsistency between the evidence of the last people to see Wayne alive and the blood test; the friends said Wayne wasn’t drunk, the blood test said he was.

A swirl of other secondary questions, too, went unasked. The coronial file contains no record of police interviewing Charlie Taylor, and Tom Cleland did not call the young man to give his evidence at the inquest.

Charlie Taylor is treated as a cipher, when it’s possible that out of all Wayne’s friends, it was Charlie Taylor who knew him best.

The Craill’s GP, Dr Heading, wasn’t called to give evidence, and Wayne’s medical files weren’t sought. In any event, Dr Kuchel describes the inference that a blackout or brain tumour might have caused Wayne to fall into the river as absurd.

“I thought that [the reference to a brain tumour] was weird,” he said. “And the blackouts thing, well I mean teenagers with rapid growth phase will often have fainting, or vasovagal attacks, or just being unwell. I would have thought that a couple of blackouts does not lead to a diagnosis of a brain tumour. That seems like a furphy to me.”

Professor Cordner adds: “You’d really be pushing it to point to that as having any plausibility as something which has operated to any effect in this case.”

Not establishing the source of alcohol in Wayne Craill’s body was Cleland’s most significant failing. But there was a rival for the honour: the Coroner didn’t ask a single question about Wayne’s sexuality. Cleland quizzed Ted Craill extensively about Wayne’s dislike of wet and cold weather. Perhaps, after the concert, the boy sought refuge from the weather under the King William street bridge, and then fell into the river? But not a word was uttered about Ted and Joan’s heartbreaking concern that Wayne might be perceived as homosexual.

Prior to being called to the inquest, Mitch Rowden was asked by police whether he thought his friend was gay. He replied that in the two months he’d know Wayne, “He liked girls’ company, I’ve never had any suspicion that he was a homosexual or that way inclined.” With Rowden in the witness box, once again, Cleland didn’t press the matter, but as with Ted, he asked Mitch whether Wayne might have gone under the bridge to escape the weather. That pattern continued with Gail Crabtree and Anne Noble.

Tom Cleland knew exactly what was going at night on the banks of the River Torrens. Hearing the Duncan case had – or at least should have – alerted him to unique dangers the place posed for a homosexual man, and, indeed, for a fair-haired kid who might be mistaken as being gay. But Duncan’s death wasn’t the only insight the Coroner had into the potential for violence on the riverbanks.

After Cleland’s inquest failed to identify Duncan’s killers, Police Commissioner Harold Salisbury appointed 10 experienced officers to continue investigations. This taskforce worked to the direction of two detectives flown in from Scotland Yard. They re-interviewed people at the scene the night Duncan died. But they also went further. Between July and September/October, 1972, the taskforce interviewed hundreds of gay men who were nowhere near the river when Duncan was thrown in.

A number of those statements contain claims of violence and harassment directed at gay men, unrelated to the Duncan matter, but on the banks of the Torrens. These statements don’t ‘solve’ the Duncan case, and they certainly don’t ‘solve’ Wayne Craill’s. They do, however, reinforce why Cleland needed to look carefully at the circumstances of the boy’s death. And they underscore the inexplicable, inescapable fact that he didn’t. We could say Duncan forced authorities to look into the Craill case, but fear of what they might find caused them not to look too hard. That’s unprovable. What can be demonstrated, though, is fear and distrust generated by the law lecturer’s killing affected the evidence given in the Craill inquest.

Now married and having left South Australia more than 30 years ago, Anne Noble remembers bits and pieces of the night Wayne Craill died. Mostly, though, she remembers him.

“He definitely wasn’t [a] drunk, that’s why we liked him. He was a bit quiet, he wasn’t your usual guy,” she said.

“He [Wayne] was a pretty boy, he had long blonde hair and he was very attractive. I think he might have been mistaken to be gay, but I don’t think he was.

“Maybe someone took him to be gay and pushed him in, but I never believed – and neither did his friends – none of us believed that he just fell in. We never believed that.”

Anne Noble says she and her friend Gail Crabtree first met Wayne Craill at Sunday afternoon riverbank concerts, which featured regularly in the ’70s. They didn’t know one another that well, and weren’t sure of one another’s surnames, but Anne thought Wayne came from a “nice family”, and that Gail was “keen” on him. On the night of the Elton John concert, it seems the attraction was mutual.

“He liked her. I remember walking up a path along the edge near the banks of the River Torrens, that’s when Wayne said, ‘C’mon Gail, lets got down to the river and walk along the river bank,’ and I said, ‘No, no Gail, that’s stupid, that’s dangerous’.”

“I could hear voices on the river bank and I thought, this is dangerous, this is not good. I don’t know who the voices were … I just had this feeling, this premonition, that it wasn’t good. And I said ‘C’mon Gail, we’ve only got 15 or 20 minutes to get up to get this bus.’ ”

Anne Noble never told Tom Cleland that story. It doesn’t appear to offer breakthrough insight into Wayne’s death, but what matters is why the teenager kept quiet about it. Part of the reason, as Anne explains, is that she and Gail had snuck out that night without their parents’ knowing.

“We weren’t doing anything wrong, but my father was very, very strict,” Anne said.

Together, the girls had raided the Crabtree’s cocktail cabinet before they left home. They didn’t want the parents knowing that, either. The major factor, though, is Duncan’s death made 16-year-old Anne Noble fear the police.

“I was scared to say too much because by this time Duncan had died, the police were [suspected of involvement] in that, and we were scared to say too much,” she said.

“We didn’t tell lies at the inquest. I didn’t lie, we just didn’t fill in some of the pieces of information because at the time we thought it might compromise our safety.”

Anne Noble can now see there was no good reason to feel that way, but she was young, and it’s the nature of fear to cloud reason. Her recollection points to a largely unappreciated aspect of the Duncan case. Something far more precious than the good reputation of SA Police was shredded on the banks of the Torrens – it was the mauling of public trust and faith that was truly significant. In turn, that affected the force’s effectiveness in investigating other matters. There’s no calculating the potential costs of that. The waves from Duncan spread wide, indeed.

The original finding still stands

The first witness to the Craill inquest took the stand at 10.30am, November 1, 1972. The Coroner’s findings were published that afternoon: death due to drowning and misadventure – the same as the burial order signed a year earlier. Alcohol and blackouts were also mentioned.

Cleland was saying, in effect, the apprentice’s own actions contributed to his death. Wayne Craill’s day in court lasted only a couple of hours, and in one of those sad, strange coincidences, it came and went on the first anniversary of his funeral. Reviewing the entire Craill file, as it exists, Professor Stephen Cordner offers a damning assessment.

“There really isn’t a plausible line in the investigatory record leading to a conclusion with any sort of credibility as to how this boy drowned, or how this boy come to be found dead in the river,” Cordner said.

The professor paused a moment, letting the implication of his last line settle, before delivering his most devastating observation.

“Because we don’t actually know that he drowned, because you can’t really tell from the postmortem… this was … a decomposed body that had been in the water for about four or five days, and the bottom line is you can’t tell.”

The first witness to the Craill inquest took the stand at 10.30am, November 1, 1972. The Coroner’s findings were published that afternoon: death due to drowning and misadventure – the same as the burial order signed a year earlier.

Despite being pulled from the Torrens’ murky waters a lifetime ago, Wayne Craill still floats half-submerged and undiscovered, near a clump of reeds. More than a metaphor, that’s how living with his death has felt to his family.

Quietly spoken, like her brother, Susan Cameron’s voice takes on an edge when speaking of it.

“Wayne was dismissed from the beginning,” she said. “And I want to understand why he was treated the way he was.”

“My parents never made peace with it, they never felt it was resolved. Those question marks were always there, right up until the end. Mum died in the early 1990s, and even when dad was dying a year or so back, I could still feel the sadness there, that wanting to know, you could feel it, even as his dementia set in.”

Susan Cameron at the Torrens. Photo: Simon Royal

Tom Cleland can’t be blamed for whatever shortcomings exist in the expert advice he was given. He certainly can’t be blamed for doing things according to the standards of his time, rather than ours. But then again, Tom Cleland didn’t fail the standards of our time, he failed something more fundamental – the standards he set for himself; “to dispel the mystery that surrounds a death”.

Like the circumstances themselves of Wayne Craill’s death, it’s highly improbable we’ll ever truly understand the Coroner’s choices.

Maybe Duncan made Tom Cleland fear what he might find if he looked too hard into Wayne Craill, but the young apprentice had started his fall through the system long before the law lecturer drowned. Tom Cleland was near the end of his life when he heard the Craill case. He was 78, his health was failing, and he’d be dead within a year. In his youth, Cleland served on the Western Front in France. He endured the horrors of World War One not for mere months, but for years on end. Then, as city Coroner for more than a quarter of a century, Tom Cleland saw once again all the meaningless and capricious ways people can die.

Perhaps it taught him that, sometimes, the innocent go without good explanation. Trusting in his own experience and ability to see, when he was actually caught in their web, Tom Cleland thought he’d found answers when he hadn’t.