Disability rate among children in care a “travesty”

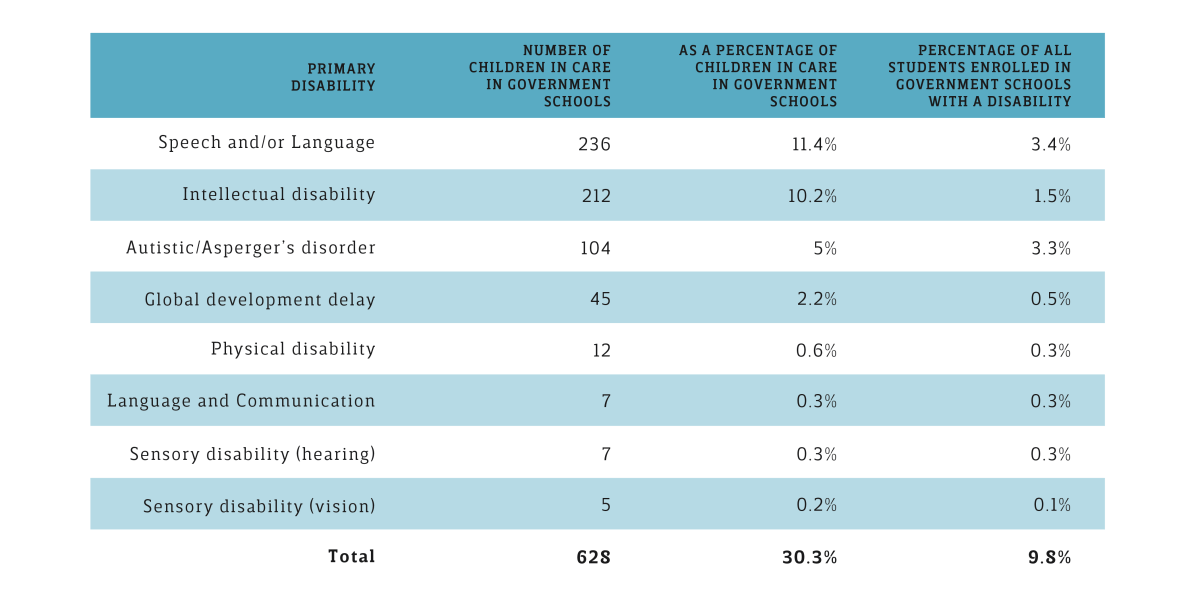

School-aged children in state care are seven times more likely to have an intellectual disability than the overall student population, data from the Education Department reveals.

Photo: AAP

Children in care are also four and a half times more likely to have developmental delays, and over three times more likely to have speech or language-related disabilities.

The findings come from a report released by South Australia’s Guardian for Children and Young People, using data collected last year by the Education Department.

According to the report, in 2018, just over 30 per cent of school-aged children in care had a disability, with the majority of those having speech or language delays.

The findings were described as a “travesty” by Australian Centre for Child Protection deputy director Tim Moore, who said the high disability rate among children in care could be partly explained by children experiencing trauma and neglect in their early years.

“As a result often they fail to meet some of their developmental milestones,” he said.

“Plus, due to the often chaotic nature of their lives, school and learning hasn’t always been a priority or something that they’ve always been given access to.

“Due to a lack of resourcing that’s often made available to families who are struggling, some of these kids really don’t thrive in their early years of life and from that a whole range of disabilities or learning delays can emerge.”

Moore said government schools were often ill-equipped to deal with the complex needs of children in state care – especially when those children had disabilities.

He said problems could escalate when children demonstrated past traumatic experiences through their behaviour at school.

“Sometimes schools don’t feel equipped to deal with them and are either not accepting the referrals or not being able to manage the kids’ behaviours, which means a lot of kids miss out on school from a very early age and really struggle as a result of that,” he said.

“Many parts of the system are really failing early on, and although there’s been significant investment in trying to improve the outcomes for kids in out-of-home-care, the reality is that we still haven’t made the progress that’s really needed.”

Table: Office of the Guardian for Children and Young People using data from the Department for Education

SA Council of Social Service CEO Ross Womersley agreed that children were more likely to have developmental delays if they experienced abuse in their early years.

He said there were many instances where children with disabilities ended up in the child protection system because families struggled to manage their children’s complex needs.

“The trauma itself may have left major damage in terms of psychological or otherwise, so they (the children) may have inhibited permanent damage that prohibits them from participating in the same way that others do,” Womersley said.

“I’m sure it’s also challenging for kids in residential care where the carers may not be organised or well instructed so as to ensure that kids are getting opportunities to develop their language and speech development skills, such as regularly reading stories and the like.”

For Womersley, the high rate of children in state care with disabilities is not surprising.

“In fact, I’m probably surprised that it’s that low,” he said.

“I might have anticipated that the numbers of kids, particularly those with more significant learning difficulties, would in fact be higher.

“It does speak to the fact that as a society we do not have the supports in place to help these most vulnerable children and their families.”

The report also revealed children in care were over four times more likely to be suspended from public schools, and 12 times more likely to be excluded when compared to the overall student population.

Guardian for Children and Young People Penny Wright said the causes for higher suspension rates for children in care were unknown, but experiences of past trauma could be attributed to challenging behaviour in the classroom.

“Many children in care have experienced trauma, both before and after coming in care,” she said.

“Some, especially those living in residential care, experience instability and rotating carers, compromising their ability to manage their emotions and complex feelings.

“These factors can all affect their school attendance, engagement when at school and overall academic performance.”

The Guardians’ report revealed children in state care struggled to meet national minimum standards across all levels of NAPLAN testing, with participation rates for students also falling below the overall student average.

“Due to the high levels of disability, a higher proportion of children and young people in care are likely to meet the criteria for an exemption,” Wright said.

“But there is no easy explanation for the higher rates of absence and withdrawals.”

Moore said greater collaboration was needed between government departments to ensure children in care experienced the same opportunities as their peers.

“I think sometimes there’s a bit of shifting of responsibilities – education sees it as a child protection issue and child protection sees it as an education issue – so these kids fall between the gaps.

“I think we really need to have a more concerted consideration of how we can work better so these kids don’t miss out or experience really life-long consequences.”

Want to comment?

Send us an email, making it clear which story you’re commenting on and including your full name (required for publication) and phone number (only for verification purposes). Please put “Reader views” in the subject.

We’ll publish the best comments in a regular “Reader Views” post. Your comments can be brief, or we can accept up to 350 words, or thereabouts.

InDaily has changed the way we receive comments. Go here for an explanation.