What has Transforming Health actually achieved?

Has the biggest overhaul in the history of South Australia’s health system worked? In the first of a two-part series on Transforming Health, we explore what SA Health has to show for it.

SA Health CEO Vickie Kaminski. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

“Before my professional reputation suffers irreparable harm, I have decided to leave,” Vickie Kaminski’s resignation letter reads.

It was late 2015, and the seasoned senior executive had decided enough was enough – quitting, mid-way through her three-year contract, as head of Canada’s largest health authority.

The excoriating resignation letter, obtained by local media, says political interference in health system decision-making had made her position untenable.

“Even though we have identified the right things to do, and the right way to do them, we are being stopped,” the letter reportedly reads.

“Many (examples of political interference) are simply rooted in an ideology of the new government that does not allow Alberta Health Services to do what needs to be, and should be done.”

A long flight over the Pacific and a year later, Kaminski was appointed to lead the largest hospital system overhaul in South Australia’s history, Transforming Health, before quickly ascending to become SA Health CEO.

In June, Kaminski was the first to publicly assert that the backflip on shifting heart services out of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital and into the new Royal Adelaide was a “political decision” on the part of the Weatherill Government.

The decision was particularly significant because it ran counter to perhaps the central axiom of Transforming Health – that specialist services must be consolidated in fewer locations to achieve best-quality care.

Kaminski told ABC Radio Adelaide at the time: “I don’t need to be consulted; the Government makes direction, I implement.”

Late last month, Transforming Health boss Dorothy Keefe was caught in a recording, leaked to the State Opposition, condemning the QEH decision as being against the unanimous advice of senior clinicians.

InDaily asked Kaminski whether she had had to alter her view of political interference in health bureaucracy since starting at SA Health, and whether she would continue as CEO for the length of her contract, but she declined to comment.

Throughout the tumultuous process of reform, some health professionals – especially doctors – have publicly warned senior bureaucrats to heed their advice on Transforming Health or risk causing patient deaths. But Kaminski and Keefe dispute these claims.

As the Government calls time on one of the most ambitious and divisive change programs in the history of the state, InDaily examines what SA Health has to show for all the effort and political pain.

Broadly, the program aims to consolidate “centres of excellence” at the state’s largest hospitals – the Royal Adelaide Hospital, Flinders Medical Centre and Lyell McEwin Hospital – while downgrading some services elsewhere, improving hospital infrastructure, absorbing services from the impending closure of the Repatriation General Hospital and moving patients into the new Royal Adelaide.

Next week, we examine in detail the views of those who’ve dedicated years of their lives to opposing Transforming Health, and from those representing medical staff on the ground.

Has it saved lives? Has it cost lives?

The early case for Transforming Health was prosecuted, in part, because too many South Australians die in hospital.

Health Minister Jack Snelling claimed that on average, 500 more people die in SA’s hospitals each year than die in the hospitals of other states and territories.

The figure has since been discredited, to the point that Keefe now considers the argument over its accuracy a distraction.

“To a certain extent, I don’t really care if it’s 100, 200, 500 – it’s too many, and we needed to bring it down,” Keefe tells InDaily.

“We used our best ability to estimate the number excess deaths that we had in our system, and we’re pretty sure that we had excess deaths in our system.”

The facts of the matter are that we were not performing as well as we should.

Keefe says she is “confident that we’re trending down (in relative hospital mortality rates) and that if we do the things that we plan to do – that are all quality activities, that that will lead to a (further) improvement.”

“We’ve used all of the techniques we can to bring it down, but we’re not finished with our changes yet.

“The buildings themselves will not bring it down, but the location of services should.”

In 2016, the Australian Medical Association (AMASA) and the South Australian Salaried Medical Officers’ Association (SASMOA) released a survey of doctors warning that Transforming Health changes were being implemented too fast and “without adequate regard for patient safety”.

Modbury Hospital surgeons warned patients that arrive with a severe airway blockage “might die because they can’t access the treatment”.

Later that year, Ambulance Employees Association state secretary Phil Palmer told a parliamentary committee that a lack of resources had caused a delayed ambulance response, potentially contributing to a patient’s death. SA Ambulance Service investigated, finding no evidence to support the claim.

Prominent Transforming Health critic Warren Jones released part of a report he said was produced by a senior SA Health clinician, suggesting hospital ward closures could lead to higher patient death rates. He would not say who had produced the report (or release the full report) other than to say that it was a senior SA Health clinician: a “very reliable source”.

But Kaminski and Keefe dismiss public claims that Transforming Health has led to, or will lead to, unnecessary patient deaths.

“Every time (SASMOA) has said somebody’s going to die, we’ve looked at it and nobody’s dying – we’re actually making those changes and we’re improving what’s happening,” Kaminski tells InDaily.

“We’re seeing that we’re actually making the gains that we thought we’d make.”

Saying patients are going to die gets attention – if you say ‘I don’t like what (Transforming Health) is doing to me’, makes you sound whiney.

Asked whether she believes doctors are being disingenuous with these claims, she says: “I think (clinicians) absolutely believe what they’re saying.”

“I’m not suggesting that (they don’t) – but it’s not being proved out in the data.”

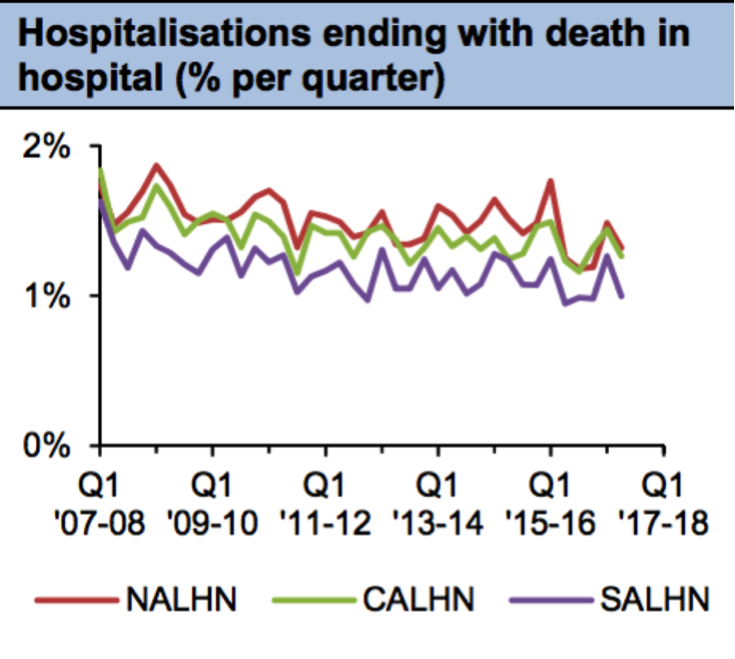

Mortality data from South Australian hospitals has fluctuated wildly since Transforming Health began in early 2015 – as that data tends to do.

Health Performance Council stats show a spike of deaths leading into the first quarter of 2015-16, followed by a sharp dip, then another peak near the beginning of 2017, and then another fall.

If Transforming Health has had a direct impact on these numbers, it’s unclear what that impact has been.

A Health Performance Council graph showing mortality rates in SA hospitals between 2007-08 and 2017-18.

We can be sure, though, that the rate of hospitalisations ending in death in SA has been trending downwards over the past decade.

The State Government has made upgrades to all of SA’s hospitals during that period.

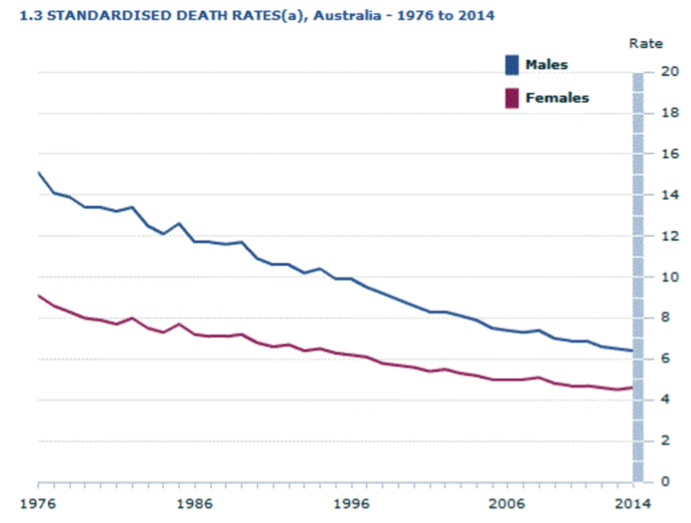

But the overall death rate across the country has also been steadily declining, in line with Australia’s aging population.

Australians are living longer, so are on average less likely to die in a given year.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data showing deaths per 1000 persons nation-wide, 1976-2014. (Deaths, Australia 3302.0)

Has it closed the budget black hole?

Kaminski concedes: “Somewhere along the line I think we lost the momentum that we had around doing it for improved outcomes, doing it for patient care.”

“And (the political atmosphere) started to slip into ‘we’re doing it to save money’… ‘it’s just an exercise to save money’ – and in fact, it wasn’t.

“We ended up behind the eight ball on that.”

But a more pragmatic interpretation might be that it happened the other way around.

While some in SA’s hospital system had been agitating for serious health reform for decades, it took Joe Hockey’s now-infamous 2014 budget to push the South Australian Government over the line.

About $600 million, slashed from the SA health system, constituted a “full-blown crisis”, Health Minister Jack Snelling warned at the time.

The State Government absorbed some but not all of the cuts in other areas of the budget, leaving a $320 million shortfall.

According to Kaminski, a reconfiguration of services through Transforming Health has already saved the health system millions of dollars but she says “money that we have saved we’ve invested somewhere else.”

“It’s not like we’ve seen a huge budget line reduction in health care.”

Transforming Health has cost, in itself, about $90 million between 2014-15 and 2016-17, according to state budget papers.

That figure includes the cost of consultants, communications and a dedicated change management leadership program.

Add to that the cost of related hospital redevelopments and the figure tops $200 million.

Keefe points out that “providing high-quality health care actually saves money in and of itself, because you don’t have adverse events if you do the right thing the first time”.

“If you don’t do an operation you don’t need to do you don’t get complications you didn’t need to have.”

Were the medical experts listened to?

Thousands of people and hundreds of medical staff participated in consultation exercises, and a series of clinical advisory committees were established, to design the final hospital reform plan – “Delivering Transforming Health” – released in March 2015.

Yet a lack of meaningful consultation has been a constant criticism of the process.

“The Transforming Health advocates ignored feedback from clinicians and were making decision on matters which they had no clinical knowledge, basis or specialist clinical qualification that gave confidence in the changes made to services,” argues SASMOA’s Bernadette Mulholland.

“External (Transforming Health) consultants came and … these consultants did not listen to what the clinicians were saying on the floor, regarding the consequences of their decisions on patients and health services with potential for severe adverse outcomes for patients.”

Kaminski says SA Health will have to design more effective consultation methods in future, but some clinicians’ expectations of consultation were not in line with reality.

“We have to look at how we do consultation differently, because everybody has said ‘not enough consultation’,” she tells InDaily.

“We’ve got to get better at getting back to people [to say] we know that you thought this, here’s what we’re doing and why we’re doing it.”

Consultation does not “mean that everything you say gets acted on,” she argues.

“If you say you’re going to consult with me then I expect that you’re going to do what I tell you to do.

“So if you don’t do it, you’re going to feel like I didn’t listen – as opposed to listen, weight it, and took a different path.”

Keefe added to that: “It’s one of those things where people sometimes don’t believe they’re being consulted if they haven’t had a face-to-face meeting with the minister, or with Vickie or myself.

“We actually involved everybody, but we didn’t always get to meet everybody face-to-face.

It’s a little like the ‘people will die’ (claim) – it’s very easy to say, but it’s not necessarily so easy to prove.

Are standards improving?

A truism in health circles is that you can hate Transforming Health, but you can’t hate the clinical standards – 284 of them, developed in 2015 by clinicians, painting a picture of what the hospital system should be able to do for South Australians.

Keefe said, then, that it was “simply not acceptable” that the system could not meet 52 of them.

“We’ve certainly made a start on most of them,” Keefe says now.

“But until all those service moves are finished, we can’t actually deliver on all of them, because a lot of the standards related to having the services in the right place to enable the models of care to be introduced.

“Of the (52) we couldn’t meet at the beginning, we’ve completed meeting more than 10 of them – but, as I say, the others we’ll complete as the service moves are completed and as the models of care are able to be fully implemented.”

In 2015 the hospital system was also failing to meet important national standards, including the principle that all patients should be attended to within four hours of arriving at an emergency department.

This standard has gone backwards.

According to state budget papers, on average, 58 per cent (actual figure) of metropolitan Adelaide hospital patients in 2015-16 were seen, admitted, discharged or treated within four hours. In 2016-17 that number had fallen to 55 per cent (estimated).

During the same period, the proportion of patients who received urgent elective surgery within clinically appropriate time also went backwards, falling from an average of 89 per cent (actual) to 86 per cent (estimated).

At the same time, emergency departments have been hit with significantly higher patient numbers – 13 per cent higher “year, over year, over year” says Kaminski – and SA Health doesn’t know why.

But other important standards – especially length-of-stay – are demonstrably improving.

According to an SA Health spokesperson, patients were spending nine fewer hours, on average, in the state’s hospitals in the early months of 2017 than they did on average in 2014-15.

Shorter length of stay means more patients can be seen and hospitals work more efficiently.

Keefe tells InDaily the shorter lengths of stay have not come at the cost of sending patients away too soon.

“We are quietly confident that the reduction in length of stay has not come at the cost of re-admissions,” she says.

“There are measures of re-admission rates and there is no signal in those measures that there’s been a change in either direction in re-admission rates.”

In addition, integrating rehabilitation services in hospitals has, according to SA Health, dramatically reduced the wait time for emergency hip fracture surgery at the Lyell McEwin Hospital. While some patients had had to wait up to 150 hours previously, in April 2017 they were waiting 21 hours on average.

Transferring: the problem

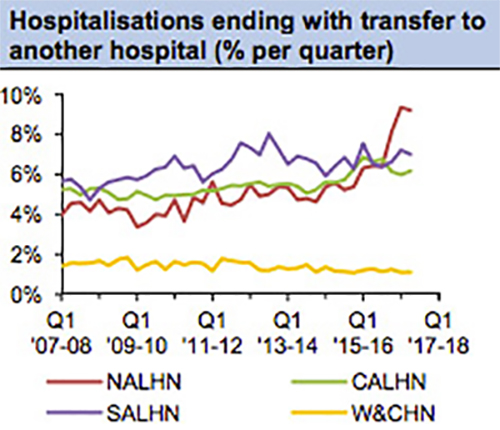

Two practically conflicting policy goals lie at the centre of the Transforming Health reform agenda.

It aims to consolidate specialist services within the state’s three major hospitals to provide highest-quality care but also to reduce the number of ambulance transfers between hospitals.

An obvious risk of creating “centres of excellence” in fewer locations is that more people may find themselves in the wrong hospital for their condition, and need an ambulance to get them to the right one.

That has been the experience in Adelaide’s North.

The proportion of hospitalisations there ending in a transfer to another hospital jumped from about six per cent in mid-2015 to 9.2 per cent by early this year.

But transfers have ticked slightly down in the South, and more so in the centre.

A Health Performance Council graph showing transfer rates at the Northern Adelaide, Central Adelaide and Southern Adelaide Local Health Networks, and the Women’s and Children’s Health Network between 2007-08 to 2017-18.

Is it really over?

As he announced cardiac services would be retained at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in June, Premier Jay Weatherill declared Transforming Health close to complete.

He said that the opening of the new Royal Adelaide Hospital (early next month) and the closure of the Repat (due before the end of the year) would mark its official end-point.

But the Opposition claims Transforming Health is ending in name only – and that the Government simply wants to get rid of an unpopular brand in time for the next state election, in March next year.

Kaminski says the hospital reform process will never be complete in South Australia, but Transforming Health, per se, has meant “moving things from Modbury to Lyell McEwen, looking at the closure, eventually, of the Repat, and moving those services into Flinders and Noarlunga (plus) getting the new Royal Adelaide Hospital open.”

“As we move into the new RAH and as we close the Repat then in fact Transforming Health, that journey … will be done.

“The piece that will never stop, that will never end … is how do we keep ourselves contemporary (…so that) as evidence changes we actually keep up with that.”

READ PART TWO: Transforming Health: The divisive washup