Saving fish from extinction sets new conservation benchmark

A DNA method explored by Flinders University scientists has not only brought a native fish back from extinction but set a new benchmark for conservation.

Along with several key industry collaborators, the researchers pioneered the use of untapped DNA information to improve the chances of success of a five-year program to reintroduce two freshwater fish species to the wetlands of the Lower Murray.

“Using the full potential of DNA analysis, we can significantly fortify our last line of defence against species and population extinction during a time of growing human-caused loss of biodiversity,” says Flinders Australian Research Council Research Fellow Professor Luciano Beheregaray.

Release of rare captive-bred animals can be expensive and time consuming, so the effort needs to pay off.

“It is paramount to understand how natural genetic diversity has been influenced by humans and historical natural processes to better inform captive breeding and reintroduction programs of any endangered species,” Professor Beheregaray says, outlining the new approach this month in the leading journal, Conservation Biology.

Along with ensuring genetic diversity of captive-bred animals, the system has the potential to improve long-term survival in the wild.

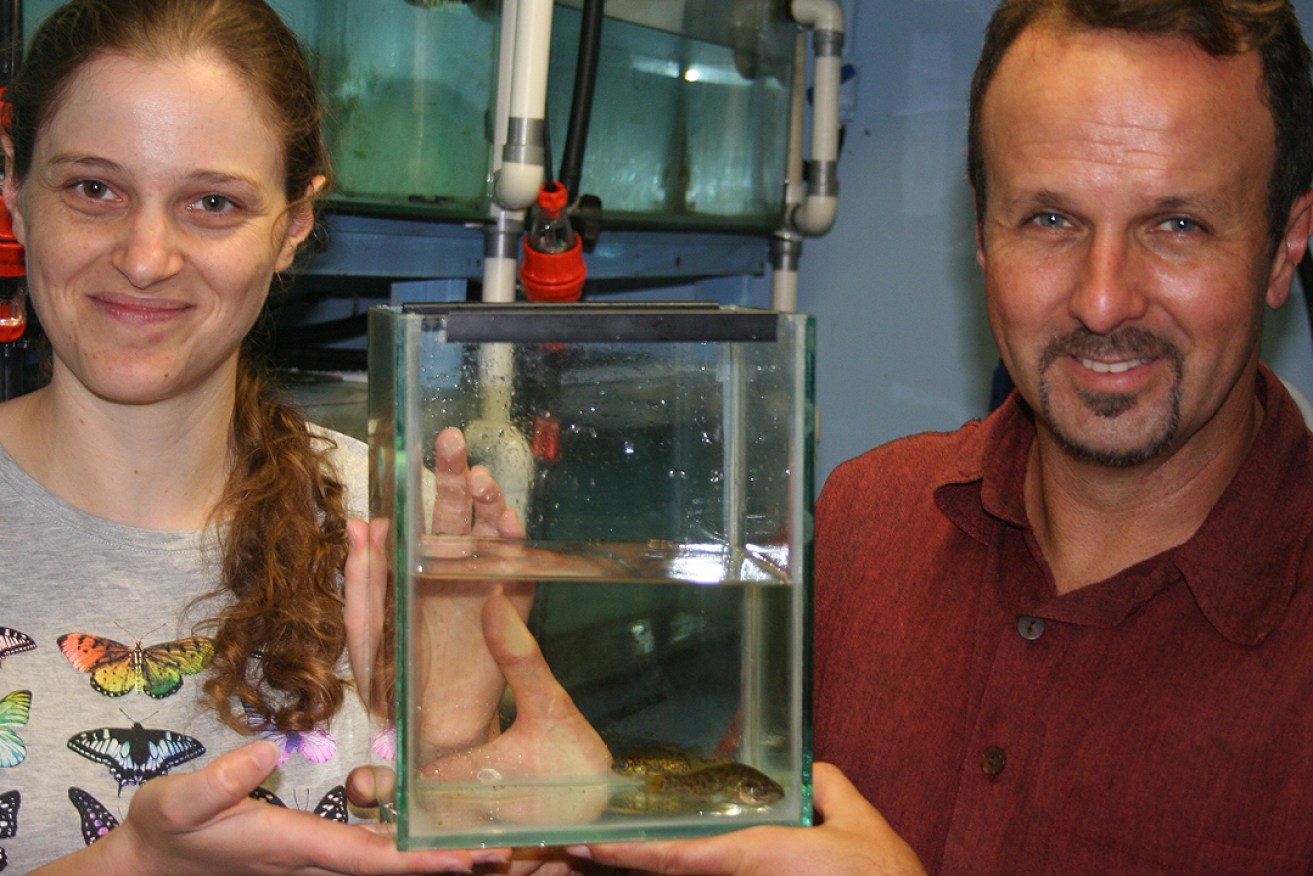

Professor Beheregaray led the successful implementation of the full potential of DNA to save two freshwater fish species – the Yarra pygmy perch (Nannoperca obscura) and southern pygmy perch (N. australis) – from extinction in lower Murray-Darling Basin wetlands in South Australia.

Following many other local extinctions of native fish since European settlement and extensive regulation of the Murray River, these fish had all but disappeared locally when their habitat dried out in 2008 during Australia’s decade-long millennium drought.

Fortunately, samples of the pygmy perch were rescued before extinction and brought to captivity.

“Captive breeding programs aim to preserve the genetic diversity held in the target population,” said Professor Beheregaray. “This is because the genetic diversity has developed through evolution and so defines that population.

“It allows the individuals to survive and reproduce in their natural habitat and adapt to environmental changes.”

“We examined the DNA of the rescued Yarra pygmy perch and found that human impacts had not yet reduced their genetic diversity, which is great news,” said fellow Flinders University researcher Dr Catherine Attard.

“DNA is inherited between generations making it possible for us to design crosses between unrelated individuals to preserve the genetic diversity of the population,” she said.

However, it was a different story with the rescued southern pygmy perch.

“In their DNA we found signs of a decrease in their genetic diversity, and that the decrease started at the time of European settlement,” Dr Attard said.

“Southern pygmy perch may struggle to persist in the lower Murray-Darling Basin due to their unnaturally low genetic diversity.

“If their numbers do not increase, we may need to consider supplementing their genetic diversity with that from other populations, which are nowadays mostly restricted to the upper reaches of the Basin.”

Historical records indicate that the southern pygmy perch population contracted in distribution due to European settlement, but that the Yarra pygmy perch population always had a narrow distribution. This explains the different genetic patterns of the species.

The Flinders research team conducted a genetic-based breeding program and produced more than 1,000 offspring for each species.

The offspring were released into the lower Murray-Darling Basin from 2011 onwards when the drought ended and some of their aquatic habitats were restored.

Monitoring of the reintroduced populations by Native Fish Australia and other agencies has shown that the pygmy perches are not only surviving but are also reproducing in the wild.

“It will still be some time before we know if their wild populations are self-sustaining, but the recapture of captive-born individuals in the wild after three years since their release is fantastic news,” says Professor Beheregaray.

This five-year study was a large collaborative effort that also included Flinders University Associate Professors James Harris and Luciana Moller, along with researchers from Native Fish Australia, the SA Museum, Murray-Darling Basin SA NRM Board and Government of SA agencies, the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR) and PIRSA research group, the SA Research and Development Institute (SARDI).