Local heroes of the forgotten war

As we honour those who died for our country, David A Grant recalls the South Australians who volunteered for a conflict largely ignored by history.

The grave of Captain Samuel Hübbe, the son of a prominent early South Australian settler. Photo: awm.gov.au

The second Boer War was Australia’s first military engagement of great significance.

The war, which raged from 1899 to 1902, differed from previous conflicts for many reasons, chief among them a distinct sense of nationhood. Because by the time of its conclusion, the six colonies had become a commonwealth.

It was also a war that impacted greatly on the social landscape due to the volume of people involved.

A relatively small attrition rate and a victorious outcome lined the nation up for a mighty fall in 1915.

People are perhaps more familiar with Gallipoli and Fromelles than they are with Bloemfontein and Standerton, but many of the troops that served in Africa enlisted again…

An estimated 16,000 Australians – including around sixty nurses, nine of whom came from South Australia – served in this engagement. The numbers are not entirely accurate though, as they include double entries where troops served with more than one contingent.

George Arthur Cobby, for example, is listed with the New South Wales Third Contingent and, later, with the 2nd Battalion, Australian Commonwealth Horse. Albert Edward Cox, who gave his address at 44 East Terrace, Adelaide, appears to be listed three times with the Australian War Memorial records.

Prior to the South African conflict, in 1885, a New South Wales contingent totalling 758 infantry soldiers, officers and artillery troops had been posted to the conflict in Sudan. There were just nine casualties from that enterprise; none of which were the result of combative operations. This would be scant consolation for the family of Private Robert Weir from New South Wales who became the first Australian to die on active duty when he succumbed to dysentery on board the hospital ship Ganges in Suakin.

Indeed, illness played a sinister role in the battles of more than a century ago. It plagued the soldiers’ fight in 1900s South Africa and claimed more Australian victims than the offensive actions of the descendants of Dutch settlers, the Boers. A total of 282 Australian soldiers were killed in action – or died as a result of wounds sustained in battle – but more than this were claimed by disease and accident. Pneumonia, dysentery and typhoid were chief among the nefarious invisible opponents.

The fighting commenced in 1899 and the first Australian contingents arrived in December of that year. Australians saw it very much as their patriotic duty to volunteer for the South African conflict, where their opponents were painted as untrained, treacherous and ill-prepared farmers.

South Australians signed up in their hundreds, with many coming from rural areas due to the equine nature of the offensive. The army relied heavily on horses for everything from transport to actual combat in what was a very mobile war.

These volunteers included Walter Herbert Follett, Leonard Harris Boucaut, Charles Harvey Atkinson, Thomas Kerr Muir and Sydney James Simper, all from the Mount Barker area. Henry Arthur Giles from Mount Pleasant also embarked, as did Andrew McGavisk, who gave his address as the “Warder’s Cottage at Adelaide Gaol”; Walter Foreman came from Frewville; James Reed from Plympton and Eugene Wickens from Stepney. Twenty-three year old Kenneth Clark gave his address as the ‘Plough and Harrow Hotel’, more familiar now as the Hotel Richmond in Rundle Mall.

More than 50 SA service personnel did not return from Africa, among them Charles Frederick Millman, whose parents lived in the Blakiston/Nairne area. He died of wounds received at Kaffirs Kraal on October 31, 1900. Then there was Albert Stephen Page, a 19-year-old coachman from Aldgate whose family resided in Murray Bridge, killed on November 29, 1900, at Rietfontein. Sergeant CE McCabe, a 27-year-old Adelaide metropolitan fireman, suffered the same fate in the engagement.

…their graves remain a long way from home, scattered across faraway fields.

John Hartly Moore, a farmer from Lobethal, was killed at Palmeitfontein on July 12, 1900. He had been a regular in the town’s cricket club and was, by all accounts, a popular figure. Indeed, a well-attended social had been held in the Lobethal Institute to farewell him. Private William Edwin Smith, from Gumeracha, was killed in action at Arundel, Cape Colony, on February 18, 1900.

Of the officer rank, Captain Samuel Hübbe, the son of prominent early South Australian Ulrich Hübbe, was killed instantly while leading his men on a charge towards Boer positions. Captain Malcolm Hipwell, from Porter Street, Parkside, died on May 25 at Kroonstadt from enteric fever (typhoid).

Surgeon Major JT Toll, a London-born resident of Port Adelaide in his mid-40s, died at sea aboard the SS Australasia, while being invalided back home to SA. George Hardey, who lived on Charles Street, Norwood, also did not return.

Other South Australians killed were John Edgar Gluyas, a railwayman from Peterborough, and trooper Herbert Prosser, a 26-year-old jeweller who lived with his family in Adelaide’s Vincent Street. From the Gawler area, troopers Bruce May, Frederick Tothill and Corporal John Heinjus were all mortal casualties. May, killed accidentally, was a son of the prominent Gawler business “May Brothers and Co.”.

Williamstown lost William Edwin Smith; further north, from the Gladstone area, Sergeant Peter Murrie and trooper Francis Mathews did not return home.

From the Barossa, Troopers Theodor Klaffer and Alexander “Alick” Nicholas fell and, to the south, from Mount Gambier, William Ewans was killed in fighting near Reitz on June 6, 1901.

That was a dark week for SA casualties. In addition to Ewens, Lance Corporal Richard Hamp was also killed. Then, three days later, on June 9, 1901, Charles Walter, Albert Marshall, Frederick Croft and Harry Main all died in action at Standerton.

Among those killed during the conflict but omitted from the commemorative plaques is Harry “Breaker” Morant. He was British-born but embarked from SA, where he later lived. He was controversially executed by firing squad for his part in the killing of unarmed prisoners in an oft-told story, later famously filmed.

Despite all this, the vast majority returned safely. The Courier newspaper on December 7, 1900, reported, in great celebratory detail, on the arrival home from Africa of Privates John Pope and George R Paltridge.

They were greeted by a large crowd after stepping off the train and were subsequently paraded as heroes up Mount Barker’s main street. Paltridge later returned to war, serving at Gallipoli before being taken prisoner by the Turks in 1917 during the Battle of Gaza.

Also returned safely was Sinclair Blue, stepson of Chief Justice Sir Samuel Way. Blue’s name appears on a 2m-high oak tablet suspended on the wall in what is known as the “Supper Room” within the Hahndorf Institute building. Along with Blue’s name, in gold lettering, appear the names of 17 former pupils of the Hahndorf College school, now the Academy building, who volunteered to serve “King and Empire”.

The tablet was unveiled, amid great ceremony, in 1904. It is perhaps a melancholy indication of the passing of time that, after several moves over the last 102 years, the panel has migrated from pride-of-place in the Academy building to a forgotten backroom, bereft both of convenient public access and local knowledge.

The 18 names listed are Sinclair Blue, Herbert Brown, Roland Cudmore, Lionel Dunn, Henry Formby, Walter Follett, Frederick Gower, FT Hall, SM Howe, RE Murray, Sydney McFarlane, Edward Mattfield, Herbert Norman, George Paltridge, George Reece, Robert Webb, Allen Wright and R De Leon.

As far as can be determined, each of Hahndorf’s 18 soldiers survived the conflict and continued life beyond the war. Dunn was invalided to Australia, but subsequently lived until 1951. Blue returned to Africa in 1914, but died there shortly after arrival, having developed pneumonia.

Cudmore was killed in a motor accident in Mildura in 1913.

Some, however, do not appear mentioned in the definitive “Official Records of the Australian Military Contingents to the War in South Africa”, suggesting that they perhaps enlisted but never embarked.

Several won promotions and two received awards for distinguishing themselves in battle.

Herbert Woolmer Brown received a DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal) after he swam, under Boer fire, across a river to retrieve punts (flat-bottomed boats) for the transport of troops.

He died in North Adelaide in 1930. His King’s and Queen’s medals, with clasps, appeared at auction as recently as 2012.

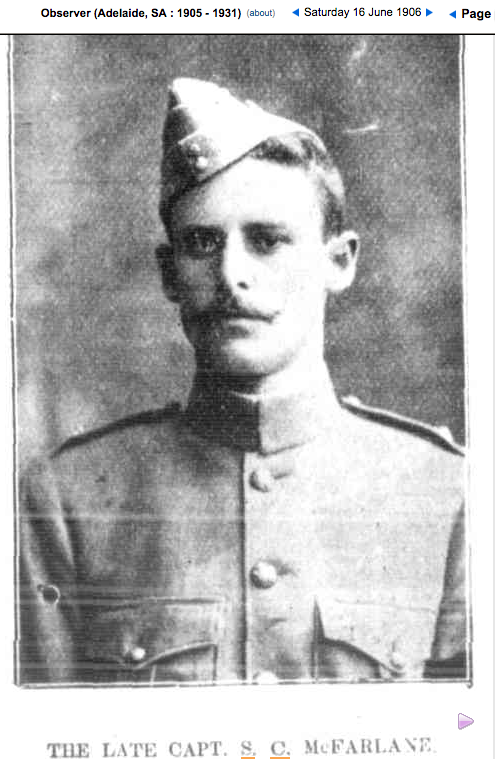

Sidney Colin McFarlane (also spelt ‘Sydney’ and ‘MacFarlane’) was awarded the DSO (Distinguished Service Order), and rose to the rank of Captain by the end of the conflict. He later resided on Fisher Street in Malvern, but was born in Angaston. His formative education was undertaken in Hahndorf before he graduated to Way College in Adelaide and, after completion of his schooling, he found work in Port Lincoln. From there he moved to Perth, and volunteered to join the fighting. Despite having no military experience, he was a fine horseman at a time when this was a valued skill to have in the job application.

But shortly after arriving in Africa, McFarlane copped a bullet to his ankle at Vet River and, after three months in local hospital, he was invalided to England to recuperate. He returned to SA, but “his desire to serve the Empire was still strong in him” so he joined the sixth contingent when it formed and returned to South Africa as a Lieutenant. He was soon promoted again, this time to Captain.

Upon cessation of hostilities, he chose to remain in South Africa where he became a successful farmer with his brother in Orange River Colony. He appears to have been highly regarded and volunteered much time to the maintenance of the graves of Australian soldiers who did not return home.

McFarlane later joined the Johannesburg Mounted Rifles and when the 1906 Zulu Rebellion erupted, he joined the fight in a quite uneven contest against the natives. On June 10, 1906, at the Battle of Mome Gorge in Natal, he was struck down by a shot to the chest. The Advertiser of Friday, July 20, 1906, contains an account of his death. His fall was broken by a comrade, Trooper Mackay, but he stated that Captain McFarlane died almost instantly, only muttering incoherently at the end.

Just 28 years old, McFarlane was buried in the Eshowe Cemetery in Natal.

People are perhaps more familiar with names such as Gallipoli and Fromelles than they are with Bloemfontein and Standerton, but many of the troops that served in Africa enlisted again to serve in World War I.

The nightmarish conditions of battle in the 1915 campaign onward are well documented, but those in Africa had to contend with their own dreadful environment, which included lice, bitterly cold nights, sweltering hot days and little opportunity to wash. They witnessed some of the worst that war can present, and yet still volunteered for service in 1915.

But as for those Adelaide men who did not leave Africa, their graves remain a long way from home, scattered across faraway fields.

They died for a conflict of which many Australians have only a vague notion.

Their contribution should be remembered today.

David A Grant is a freelance writer.

![Courier[1]](http://wp.indaily.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Courier11.jpg?w=1200quality=90)