Special report: “Shock” therapy in SA

The technology has improved. Today's results are often miraculous; sometimes catastrophic.

Electroconvulsive therapy was used to treat nearly 500 South Australians during the past financial year.

The treatment is performed thousands of times each year in SA.

Despite the horrific reputation “shock therapy” acquired in the 1970s with its depiction in films such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a large body of evidence suggests modern ECT is an effective treatment of last resort for major depression and other serious mental illness.

“People are horrified by the thought … that we still do this,” concedes Michelle Atchison, the SA Branch Chair of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.

“It sounds extraordinarily barbaric (but) it can be life-saving.

“People can get so depressed that they can believe that they’re dying … and they stop eating, they stop drinking; they say they don’t deserve to eat, they don’t deserve to drink.

“They have delusions that they’re rotting inside or they’re not worthy of having any treatment.

“It’s an appalling illness when it’s like that, and in the old days (before ECT) people would have died.”

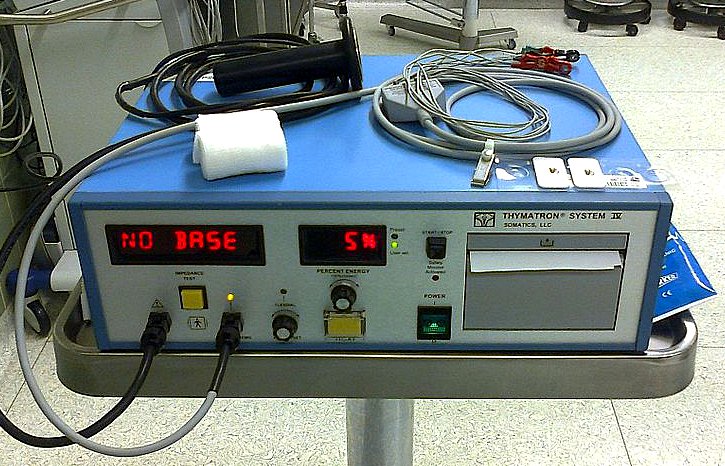

ECT involves passing an electrical current through the brain while a patient is under a general anaesthetic.

Precisely how the resulting seizure often wrests patients out of life-threatening depression and other severe mental illnesses is poorly understood.

But ECT can also pose serious risks to the brain.

At worst, ECT can strip great chunks from a person’s long term memory and hobble short-term memory.

It can also impair the formation of new memories after the treatment.

There are also risks to the heart, and a possible, but as yet undemonstrated link to some cases of stoke (see: SA Guidelines for ECT, page 15).

“I’ve had people who say ‘I can’t remember the day I got married’, or ‘I can’t remember the birth of my child’,” says Atchison.

“It can be quite upsetting and distressing.”

“(But) some people are quite okay with understanding that that’s the trade-off.”

With and without consent

Around 25 people who received ECT in 2013-14 did not consent to the treatment themselves.

The Mental Health Act states that consent to an episode of ECT “is not required” if a psychiatrist considers that there is an urgent need for the treatment, for the sake of a patient’s wellbeing, and “in the circumstances it is not practicable to obtain that consent”.

Further, a medical practitioner or psychiatrist can apply to the Guardianship Board to perform a course of up to 12 episodes of ECT, over a maximum of three months, without patient consent.

The practitioner may then apply to the board to perform a subsequent course of treatment.

Atchinson said patients suffering severe episodes of major depression or psychosis are often unable to provide informed consent to ECT treatment which may save their life.

However, some consumer advocates believe ECT should never be undertaken without the informed consent of the patient – even if the treatment could save their life.

Sandra Miller was one of two mental health consumer representatives on the ECT Advisory Committee which helped formulate SA Health’s statewide guidelines for the practice of ECT.

“If a person has cancer they can refuse treatment and not have to have it and rightly so, but not when you’ve got a mental illness,” she said.

Since the Advance Care Directives Act passed parliament in 2013, South Australians have been able to apply for a directive to prohibit certain treatments, including ECT, from being performed on them in future.

However, an application may still be made to the Guardianship Board to consider the validity of the directive.

Miller was almost forced to undergo ECT in the mid-1990s, but was allowed not to have the procedure because of repeated calls made by members of her family to stop it going ahead.

“They were going to give me what they called an emergency treatment at 8 o’clock the next day, and didn’t tell me or my family till 4 o’clock the night before,” Miller recalls.

“My (parents) said that I didn’t want ECT under any circumstances, and then they were still going to go ahead with it.

“In the end they cancelled because lots of people rang and said not to give it to me.”

Miller says she is relieved to have “escaped” the treatment, and that discussions with friends who have undergone ECT have convinced her the treatment is barbaric and damaging.

“It’s just appalling that they still do that in the 21st century, and they make people have it against their will as well. It’s just appalling.

“People forget things. People forget huge chunks of their lives.

“If people want to have it and if it helps them, that’s different. But when they make people have it against their will, I just think it’s so wrong.”

Modbury Hospital does not meet ECT guidelines

Statewide guidelines and mandatory standards for the practise of ECT were signed off by the SA Health executive less than a fortnight ago.

The guidelines state that, to provide patients with privacy and autonomy, an ECT suite should consist of a minimum of three rooms: a waiting area, a treatment room and a recovery room.

But Modbury Hospital practices ECT in one room.

The Repatriation General Hospital also conducts the treatment in one room, but that is allowed for in the guidelines because that room is a general hospital theatre.

“Currently, patients waiting for and recovering from ECT do so in a safe environment within the general day procedure area but both hospitals are working towards establishing dedicated ECT waiting and recovery areas,” an SA Health spokesperson told InDaily.

The spokesperson said the hospitals had a six-year “deadline” to meet the guidelines.

“The recently released ECT Policy Guidelines outline particular requirements for the set up of treatment, recovery and waiting areas, which all ECT sites will need to meet within two accreditation cycles.

“At Modbury Hospital and Repatriation General Hospital, ECT procedures take place in dedicated treatment areas, as per the guidelines.”

Atchison told InDaily the ECT facilities at Modbury and the Repat were safe, but not ideal.

“We have looked at both those units and we know that what they’re doing is safe (but) it’s not as ideal as it could be,” Atchison says.

“For privacy reasons, being able to have your treatment of ECT out of sight of other people is ideal.

“Having it behind a curtain, where other people can hear, especially if you’re waiting to have ECT – it’s just not ideal.

“If we knew a service was giving ECT unsafely … we would have to approach the hospital; we would have to say do you want to look at their accreditation, etcetera.”

SA Health would not say whether the Modbury ECT facility was “behind a curtain”.

Early models

Electroconvulsive therapy was pioneered in Australia at Parkside Lunatic Asylum in Adelaide – now known as Glenside Hospital.

ECT machines were not available in Australia, so psychiatrists at Parkside teamed up with the Adelaide University Physics Department to build a machine out of available materials.

The machines timed bursts of electricity using telephone dials: the only accurate timing measures available during the wartime period.

“Over the course of time, the discovered that dialing nine (produced the best outcomes),” says Dr David Buob of the Glenside Historical Society.

According to Buob, ECT was practised sans anaesthetic and muscle relaxants at the time, and would have looked much like that terrifying scene in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

“It would have been quite frightening,” he says.

“You needed to be held down … to try and control the epileptic seizure.”

The early versions of the treatment may have been barbaric, but they replaced even more dubious methods of treating severe mental illness – including the practice of placing non-diabetic mental health patients in diabetic comas.

Tomorrow, InDaily will have the story of two women who underwent ECT: one credits the treatment with rescuing her from of absolute misery; the other says it has devastated her life.