A tragic Christmas Tale: Ooldea, 1941

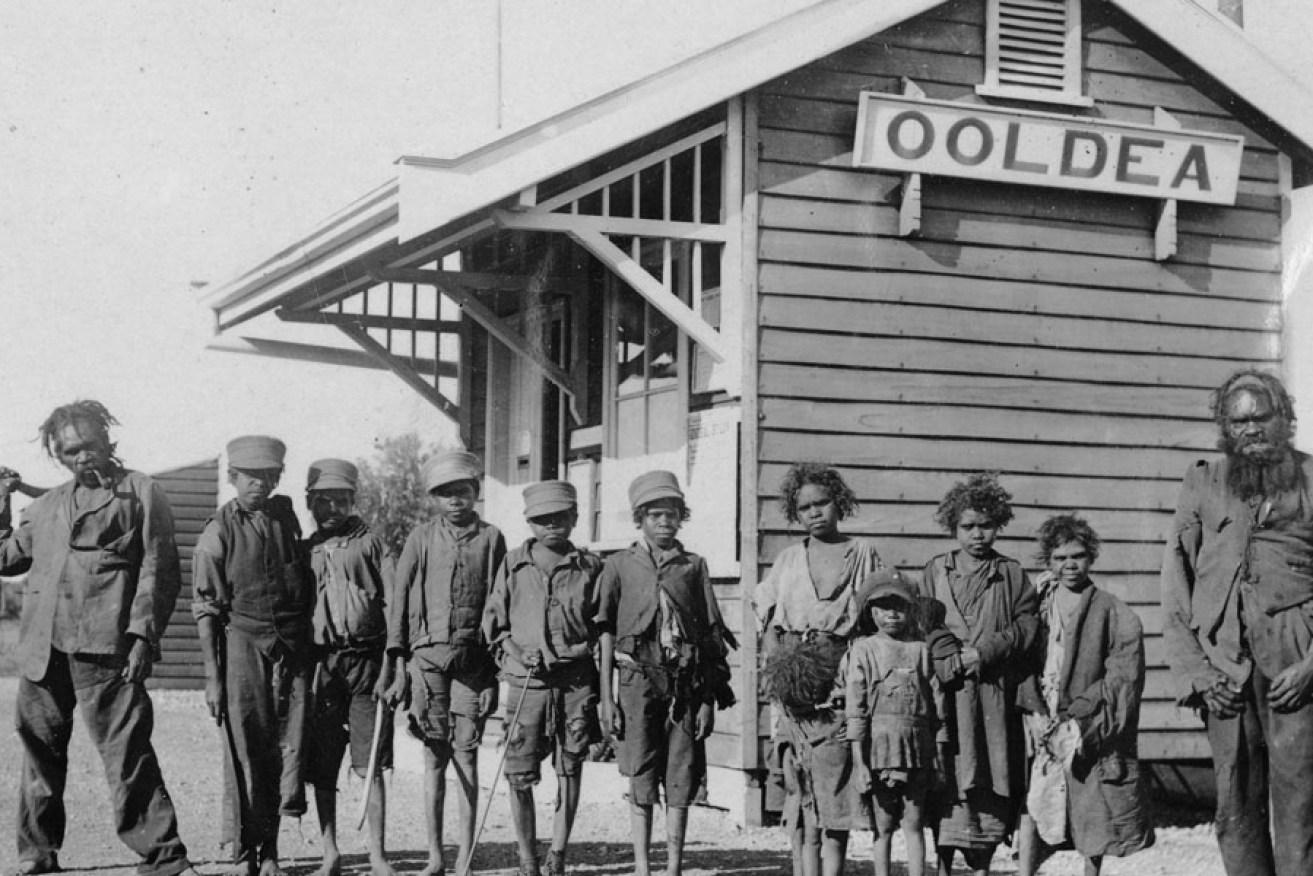

Aboriginal men and children outside the Ooldea post office, circa 1920. Photo: State Library of South Australia

It’s Christmas Eve, 1941.

At the Ooldea Mission, an un-named Aboriginal man with a life-threatening leg injury is placed on a wooden cart and transported the four miles to the Ooldea Siding, a stop on the Trans-Australian line, 500 miles northwest of Adelaide, but much further by road or rail. Arrangements have been made for the fast goods train to evacuate him to Kalgoorlie.

The siding consists of a few houses, a one-room station building, two water tanks and some 20 or 30 people – employees of Commonwealth Railways and their dependents. These white people are prohibited from employing Aboriginal people, who in turn are prohibited from buying goods from the ‘tea and sugar’ train that provides basic foodstuffs to (white) people at dozens of similar small outposts along the line.

Swaddled in bandages, the injured man lies on the cart at dusk, a small group around him including his Aboriginal escort and Harrie Green, missioner-in-charge of Ooldea Mission. The train approaches slowly from the east, slow enough for the guard to drop off several packages for the Ooldea ganger. But it does not stop. The ganger’s wife gestures frantically as the train gathers speed and leaves the siding behind.

The failure of the train to stop is the latest in a string of conflicts between Harrie Green and Commonwealth and State Government authorities. At the time, Aboriginal people on the Trans-Australian line are living marginal lives as a consequence of both the usurpation of their lands and traditional economy by white settlers and the South Australian government’s chronic underfunding of the Aborigines Department. They are forced to barter or beg for food. Their presence on the line and their visibility to travellers is a source of annoyance and anxiety for the Aborigines Department and Commonwealth Railways.

Four years earlier, in 1937, the mayor of Port Augusta calls a meeting to discuss the town’s ‘Aboriginal problem’. The Aborigines Department is represented through the arch-conservative Professor John Cleland and the Chief Protector of Aborigines, Milroy Trail McLean. At the meeting, calls are made for all Aboriginal residents of Port Augusta to be gathered onto a small pastoral reserve and held there ‘under some supervision’. Chief Protector McLean goes a step further, favouring the extension of this apartheid to all Aboriginal people living along the Trans-Australian line:

I consider this the only practical way of meeting the situation which now exists. It is quite evident that the black, in their present condition, and the whites will not mix without damage to both …

Aboriginal people were generally unwanted throughout rural South Australia, but especially in the western parts of the State. All along the Trans-Australian line they were deliberately excluded from medical services. In 1938, the Reverend Tom Jones of the Bush Church Aid Society informs McLean that the Cook Hospital, approximately 90 miles west of Ooldea, will no longer admit Aboriginal patients. He explains:

Cook Hospital is a small, two ward building with two beds in each ward. To receive an Aboriginal patient means that he or she must have a ward to themselves—because of the objection the whites have to being accommodated in the same room.

Meanwhile, Dr RW Gibson resorts to performing emergency operations on Aboriginal patients in the mortuary of the Ceduna Hospital, 160 miles south of Ooldea. He writes to McLean:

As it is I’ve done two emergency operations on aborigines within the last 3 months in the mortuary of the Hospital, & these cases have been nursed in that place by the sisters to their extreme inconvenience.

No doubt this ‘extreme inconvenience’ is shared by the patients themselves.

Three years prior to the Christmas Eve incident, Commonwealth Railways proved itself unsympathetic to Aboriginal medical patients. Reverend Jones had reported the case of an Aboriginal woman whose arm had been crushed under the wheels of a train whilst alighting:

[The fettlers at Wynbring] rang [Port] Augusta for permission to use an engine to take her over to Cook and this was refused and the woman was brought into Cook on a trolley and arrived nearly frozen to death after midnight almost 11 hours after the accident [original emphasis].

Indeed, Commonwealth Railways is generally unsympathetic to Aboriginal people. Their employees are directed ‘not to encourage aboriginals to trespass on railway premises and … not sell, barter, exchange, give … any food, clothing or money to any Aboriginal native of Australia or half-caste of that race’.

The Ooldeans are unwanted in their own country, and they know it. When renowned anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt do fieldwork at Ooldea, just a few months before the Christmas Eve incident, they find a ‘general hostility’ towards Aboriginal culture and a keen understanding among Aboriginal people of the unfairness of their relationship with whites. The Ooldeans were disillusioned and depressed, a symptom of what the Berndts called the ‘second stage of culture contact’.

The Aboriginal man who lies on the cart on Christmas Eve, 1941, as the fast goods train departs, had been speared in the leg several days earlier. Harrie Green, the missioner-in-charge, continues to apply ‘hot fomentations and antiflo’ to his injuries. No further attempts are made to evacuate him.

At 7 am on Boxing Day, Harrie Green is called over to the injured man’s camp. He finds his patient to be bleeding ‘rather badly’ from one of his wounds and in a delirious state. He dies within an hour and a half. Of the failure of the goods train to stop, Green writes:

… the [Commonwealth] railway people at the Siding are very upset about it … & feel that the neglect was, because he was a Native, & so lost his life.

There is no official inquiry into this matter, though the head of the Aborigines Department asks for and receives an explanation of sorts from the Commonwealth Rail authorities at Port Augusta. Skinner, the Chief Traffic Manager there, insists there was a breakdown in the relay of Green’s message, that the patient and his escorts were presumably standing ‘on the other side of the line from which the guard threw off the goods for Oldea’ and promises that a lamp will be placed at the siding to assist in signalling in the future.

The matter is closed. There is no acknowledgement of the frantic gesturing of the ganger’s wife and the speed of the train as it entered and left the siding.

The Ooldeans and Harrie Green will have many battles with Commonwealth and State authorities over the next decade, until their controversial removal from Ooldea to Colona Station (renamed Yalata) in the early 1950s.

Here, under the supervision of the Lutheran Church, the segregation of the Ooldeans from white society – the program favoured by the white residents of Port Augusta – will be almost complete.

Cameron Raynes is an Adelaide writer.